No whites nor shred of camo, yet Dad and I inched forward toward a Dall sheep ram just over the ridge and across a small valley.

It was the twenty third day of our hunt. For weeks we had been living like monks high in the rocky monastery of Alaska’s Chugach Mountains, speaking only in whispers, paranoid the rams could hear us. We were haggard, but somehow we remained sharp.

Outside the tent, we crawled on hands and knees to avoid being silhouetted against the glacier. I laid my rifle on a rock, my cold finger wrapped around the cold trigger. Hope surged wildly in this moment—our string of foibles could end with this single shot. Know thy gun, I thought, as I pulled my rifle in tight with embrace; we spooned together perfectly.

The shot echoed through the icy mountain range. The sheep flinched, then froze; it neither wobbled nor staggered. The shot felt so solid! It seemed impossible to have missed.

***

Six months prior, Dad and I drew the tags. It was sweet elation. I imagined the pride I would feel in finally reaching my goal of taking down a record-breaking ram. I spent my morning daydreaming of all the ways I’d celebrate, but that afternoon that I found myself collapsed in front of an elevator completely unable to move my right leg.

I was promptly admitted to the hospital for emergency surgery to reduce a herniated lumbar disc. The pain was unbearable. When he came to visit me in the hospital, Dad, a sheep hunting fanatic and registered guide, couldn’t help but remind me the season would open in just a few weeks.

“So how fast can ya heal?” he asked.

I gave a drowsy chuckle. I wasn’t about to give up the season before it even began. “I wouldn’t miss it for the world,” I told him.

***

This was sacred territory; few other vertical-peak-saturated areas mystically produce Fibonacci-spiraled sheep like the ones here. Drawing odds are less than one percent. Foreboding weighed heavy. This was brutal. Because of my injury, I was forced to remain under a 25-pound weight restriction throughout the hunt. I whispered continuous prayers—and not just for big sheep. Uneasiness festered as the word “sacrifice” repeated in my head.

One night, we slept right where we stopped for the day, two miles from camp. Shivering all night under a wet space blanket, I hoped maybe this unconventional effort would pay off. The word “sacrifice” surfaced again. Surely this sacrificed comfort. Maybe that is what the voice in my head had meant. However, it was shaky intuition based in mild sleep deprivation, so I pushed the voice out of my mind and tried to sleep.

Starting before dawn, boulders and fog provided the fickle cover necessary to get within 400 yards of rams. But luck took us only that far. A break in the fog presented us with a fleeting view of half the rams retreating to the rocks.

“They’re gone,” Dad said in disbelief.

It could not end like this. Having worked toward this moment for so long, the speed of our failure was overwhelming. It’s disorienting how hunting, how life, can sour so quickly. No one said a word. Breaking awkward silence, I asked meekly, “Has the fat lady sung?” After no response, I hugged Dad, and he cracked with emotion. His jaw clenched, nostrils flared and eyes watered. He swallowed hard. This was deep and raw disappointment. He doesn’t go hunting each year as he does just to fill a tag. A ram like this a veritable unicorn.

Since we spooked the sheep, we figured it was time to leave. The next morning, as we dejectedly packed up our gear. I took one last look across the hills and there they were; rams grazing in their bowl as if nothing happened.

The sheep’s return was a miracle; it offered renewed hope and another chance for success we couldn’t pass up. We had to stay.

We were out of food, and arranged a drop via satellite phone from our pilot friend, Bill. Later, at the rising hum of Bill’s approach, we took our positions and readied the air–to–ground radio. Bill lined up overhead. A white bag fell from the plane, hit the ground once, then rocketed between us knocking the radio from Dad’s hand. Bill flew off unaware of his accuracy while we managed to laugh at being unscathed.

Restocked, we devised a new plan for the next couple days. Again, we got in range of the rams, but again they spooked. They bunched together, hit the rocks, and kept climbing, eventually disappearing straight over the top.

But the hunt continued, as the permit was good for any ram. Besides, Dad and I both needed more time getting a charge from nature. In drinking wild water, gray with toxin-absorbing mineral-rich glacial silt, sheep hunting nourishes the soul. As a homeschooling mom, the break was rejuvenating, despite the rigors and challenges.

Our next option was a large ram with one severely, cleanly broken horn, but then even Broken Horn was gone. Two other rams remained, providing our chance for a meat sheep, though resigning to such in this permit area is sinful and I refuse. The hunt is over.

“You givin’ up already?” Bill said when he answered our call for a pick-up.

I was too cold to respond quickly.

“Don’t you wanna keep going?” he asked in assumption.

I did. Of course, I did.

“Dad, if you want to quit, I would be at peace with it,” I said.

“No, no. But if you want to go home, I would totally understand at this point,” he responded. Though we were both being forgiving and understanding, it was a stubborn stalemate. Neither would quit first.

The meaning of the word “sacrifice” finally hit me: Time.

Time means different things to mortals than to mountains. I couldn’t shake the feeling that some natural, powerful force was trying to teach me something. We had to sacrifice not the hunt, but more time—more discomfort, more defeat. It was only temporary, after all. Everything is, I reminded myself.

Bill flew us over to a second glacier, which was indeed colder. Instead of happy, gurgling chirps as the first glacier sang, this glacier cracked and boomed. Deep within the ice, a raging river could be heard, even over the wind.

We glassed for a day to determine which direction to go when a band of sheep appeared, startlingly close. Our hearts were rightly set ablaze to see a massive ram among them. Unbeknownst to us, this ram had already been the focus of two other serious hunters this season. Repeated attempts to sneak closer kept getting us stranded only 100 feet from the tent, and we were forced to belly crawl back. We sagaciously chanted “patience” to ourselves, playfully pretending we were monks relegated to a tent monastery. More days passed, sipping green tea and studying sheep movements. We could not blow it. Not again.

The biggest ram lazily plodded in seemingly pre-planned motions, saving energy. Once, he flopped down hard on a little ridge, welcoming the slight rise that reduced how far he had to lay his mass down. His head rolled back in a slow whiplash, heavy with horns. Fat neck rolls stopped his head from turning to look back at his buddies. He had summered well. His name became Chubby.

Finally, the fog was on our side. Striking boldly out across a wide swath of glacier, we froze for seconds that felt like hours as the shifting fog parted, opening a tunnel of visibility to the sheep. The tunnel in the fog rolled on, and we exhaled, praying they had not seen movement.

Sneaking to one end of a large rock formation, we saw part of the band and waited there for hours. But they would not budge; they likely sensed us.

So, we crested a different part of the hill, and spotted Chubby roughly 300 yards away, in the center of the group. Low-crawling carefully to the rock promising the best rest, I gently set down my hand-carved English walnut .270 rifle, careful to protect its finish. Dad carved it as a wedding gift to my husband and me almost 14 years ago. Wrapping a cold finger around a colder trigger, welcoming the coming closure, gun and shooter became one.

And I missed.

As a former high-school air rifle champion and coach of a multi-year championship team of the same, I was embarrassed. Perhaps an oily bore, which can sabotage first shots, was to blame. But after a second shot, Chubby drops and rolls in an instant.

As a former high-school air rifle champion and coach of a multi-year championship team of the same, I was embarrassed. Perhaps an oily bore, which can sabotage first shots, was to blame. But after a second shot, Chubby drops and rolls in an instant.

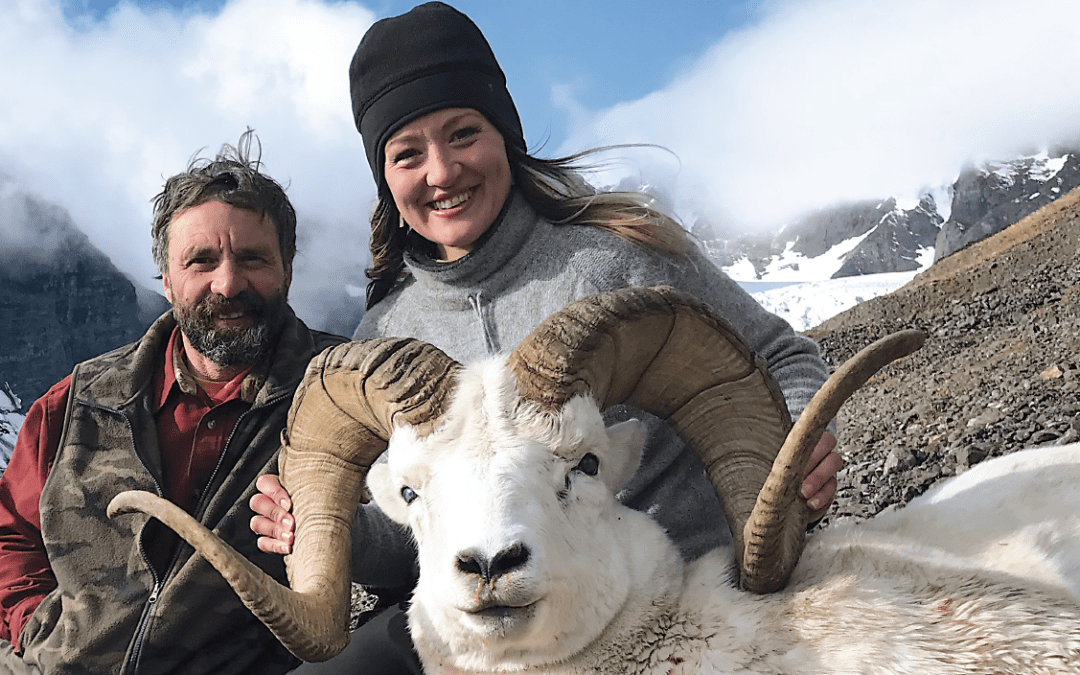

Adjusting to the moment took work, like waking up from a dream. Our time in the Mountain Monastery as whispering monks was instantly over— a spell broken. Dad still had the binocular glued to his face, so I grabbed his arm and some bizarre squealing sound came out of me; apparently, vocal cords need a warm-up after whispering for days. However, the meditative, incredulous mood persisted as we approached the ram that had given himself.

Astonishingly, Chubby was a relatively young ram. It wouldn’t be until nearly midnight of the day we came out of the field that a tape measure was finally be wrapped around the horn. It showed one side at 45 2/8 inches, and the other 44 inches. He conservatively green scored 179. Dad’s jaw dropped in stunned silence. Chubby officially scored 175 6/8, sitting at spot number 77 in the Boone and Crockett All Time Record Book, the 4th largest ram ever taken by a woman, and the largest taken by a woman in 55 years, right after Rita Oney and Eleanor O’Connor’s 1963 rams, which both scored 177 4/8. Furthermore, Chubby is the longest horned Dall’s sheep ever taken by a woman. Rita was a family friend, so I am grateful to approach her and Eleanor’s accomplishments. Chubby exemplified his name in body, as well: 20 pounds of fat usable for balms and salves accompanied more than 100 pounds of meat.

Perhaps it is true, that the animal chooses hunter, and not the other way around. Even if that’s the case, sheep care not about our women or men. Sheep care not for the money spent, nor the disappointment of other hunters who went home empty-handed. They remain indifferent, just as the ancient mountains do, to the foibles of humans. Only we count our foibles, our money, days, hours, yards, pounds and look for signs from God. But when God does send signs, they are most apparent, I’d say, through His sheep.

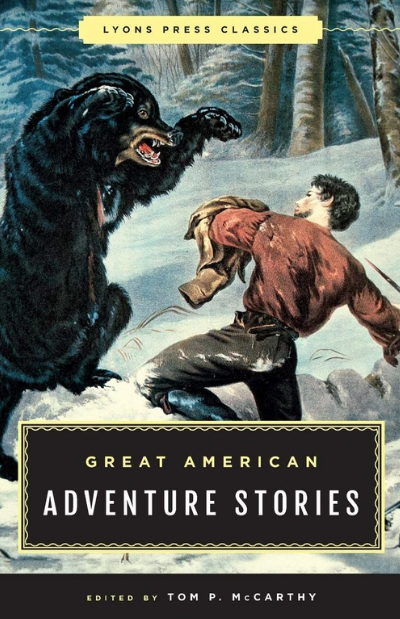

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today. Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.