The men and women who studied under Howard Pyle all but dominated American illustration during the first half of the 20th century.

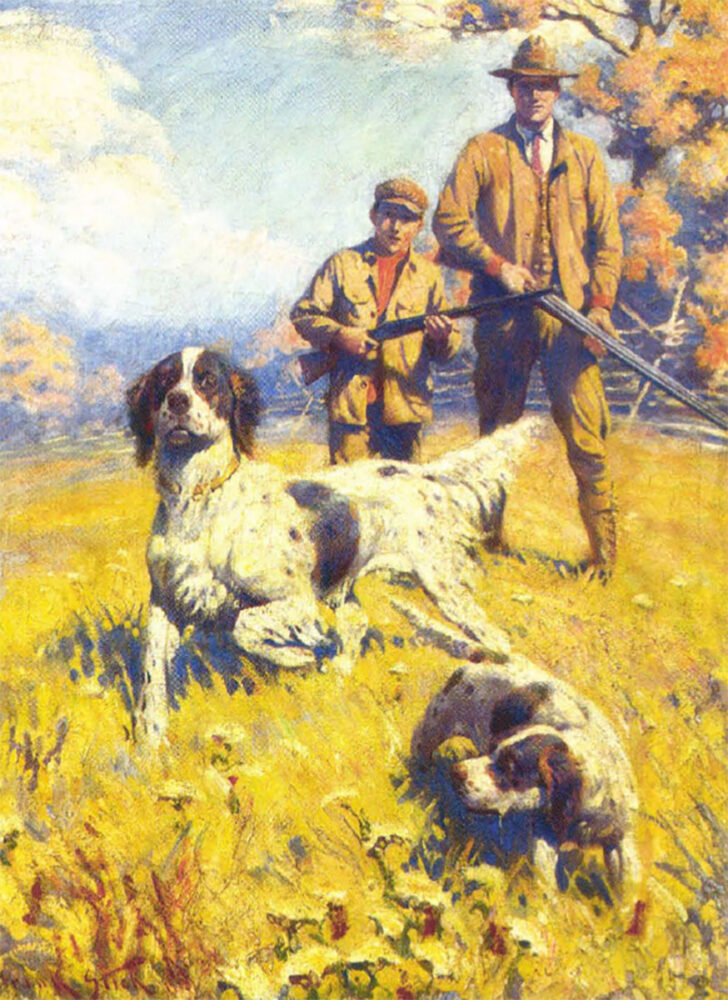

Frank Stick was another prolific painter of the outdoor life, such as this 1930s oil of a father and son hunting over a brace of setters.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Howard Pyle of Wilmington, Delaware, was most popular illustrator in America. He had only one serious rival in this respect: his old friend Arthur Burdett Frost, who lived nearby in Convent Station, New Jersey, and with whom Pyle had “come up” in the late-1870s while both were on the art staff of Harpers, the New York City-based publishing house. Although stylistically very different — Frost was more conventional and “homespun,” Pyle more innovative and worldly — they’d followed similar career paths since then, enjoying enormous success along the way, and by the early 1900s the two friends stood shoulder-to-shoulder at the top of their profession.

It was the high-water mark of the period art historians would come to refer to as “The Golden Age of Illustration,” a period in which advances in the technology of printing had made high-quality color reproduction affordable, and thus available to the “mass market.” It was a period, too, in which an increasingly large, increasingly affluent, increasingly well-educated middle class comprised a burgeoning audience for books, magazines and other illustrated materials.

Drawings and engravings had long been the dominant forms of illustration — it was for such “single color” work that Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington, for example, established their early reputations. But now painting took center stage. It was a more demanding medium, to be sure, requiring more skill and sophistication on the part of the artist. And, by the same token, it was capable of a vastly greater range of emotion, expression and drama. It created more excitement, engaged the imagination more completely, tapped deeper into the reader-viewer’s own experiences, affinities and, yes, longings.

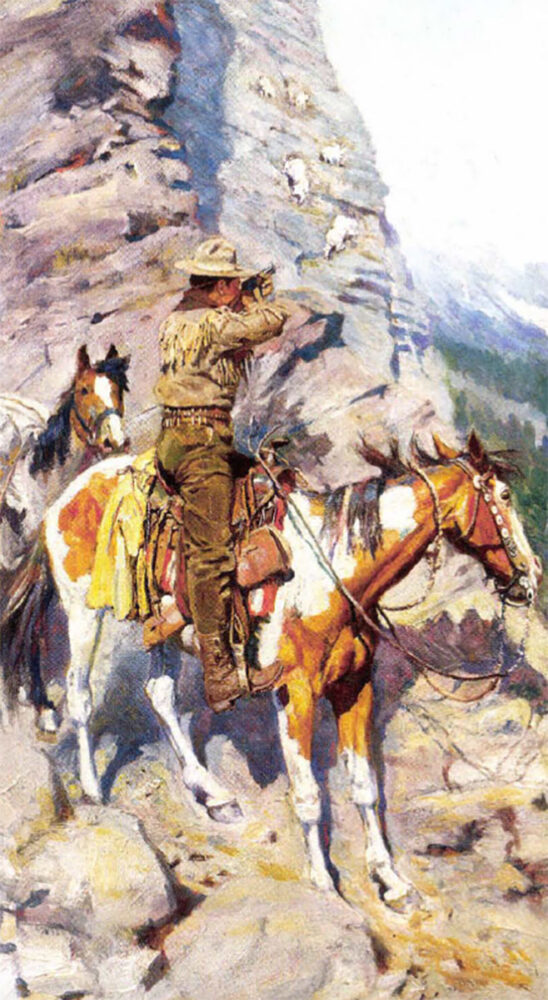

Goodwin was only 27 when he created this striking oil-on canvas, Shooting Mountain Goats, in 1909.

At the same time, Americans were taking to the outdoors as never before. In the October 1978 issue of American Heritage, John G. Mitchell offered several piquant observations about this cultural phenomenon. Noting that under the old Puritan ethic Americans hunted and fished not for sport but in order to eat, he remarked “Now, rod and gun could be perceived not only as tools of subsistence but as accouterments of a new aristocracy. Now, more often than not, the fellow with burrs on his cuffs would be hailed as a pillar of the community.

“By most hindsight accounts, the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first decade or so of the 20th fall within a period that might fairly be called the gilded age of field sports. In the cities of the East, thousands of well-to-do gentlemen turned toward the out-of-doors with a passion and a purpose that would have shocked the sensibilities of their pragmatic forefathers. Bankers and lawyers, doctors and professors, merchants and ministers donned their heavy tweeds and streamed into the countryside in quest of woodcock and quail and mallard and deer and trout . . ..”

Chronologically, this “gilded age of field Sports” corresponded closely with the Golden Age of Illustration: 1880-1920, give or take a few years on either end. They came together in the work of Frost, whose “Shooting Pictures” portfolio, published to tremendous acclaim in 1895, earned him the title “the sportsman’s artist” — an honorific that persists to this day.

Pyle, for his part, did only a handful of illustrations depicting the outdoor life. Instead, he is best remembered for his luminous, richly detailed images of literary-historical figures and events — Robin Hood, King Arthur, the Revolutionary War, etc. — images of such startling depth and complexity that they established new standards for the genre.

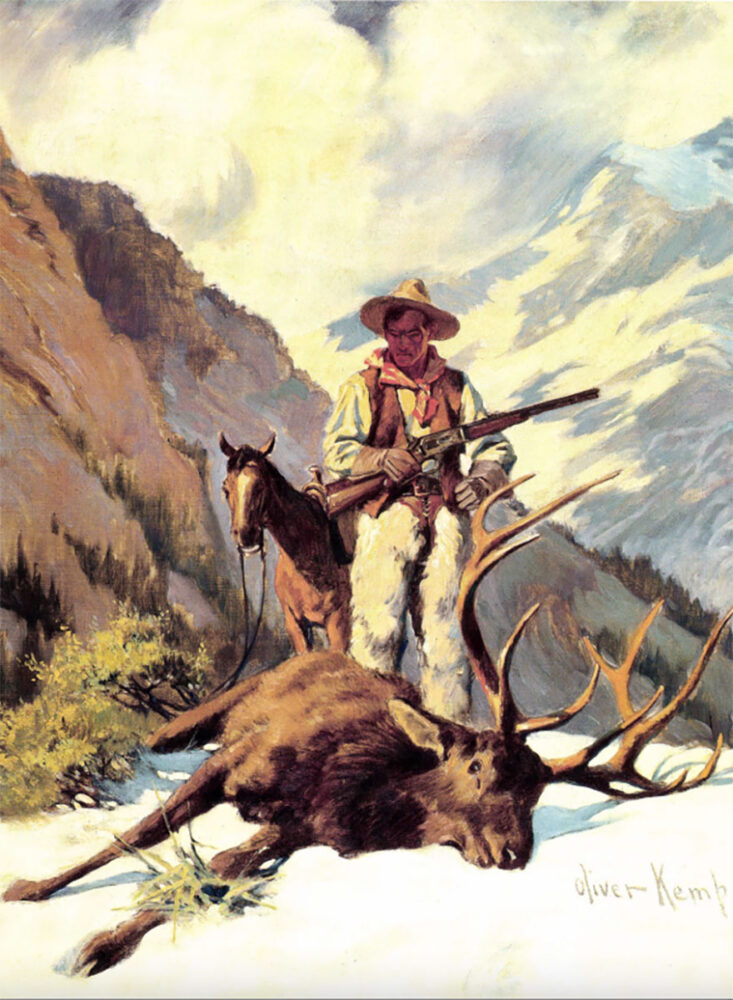

Oliver Kemp’s portrait of an elk hunter, painted in the 1920s.

Through his students, however, Pyle’s impact and influence on American sporting art would ultimately prove hardly less significant than Frost’s. From 1894, when he began teaching a course in illustration at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, until 1910, when he departed for an extended stay in Italy that was cut short by his death the following year, Howard Pyle attracted a group of young, eager-to-learn artists whose collective talent was unsurpassed and whose collective accomplishments in the realm of illustration remain unprecedented. Maxfield Parrish and N.G Wyeth are perhaps the two most famous names today, but at the time there were many others who were equally well regarded: Stanley Arthurs, Thornton Oakley, Elizabeth Shippen Green, Frank Schoonover, Harvey Dunn . . . the list goes on. The men and women who studied under Howard Pyle all but dominated American illustration during the first half of the 20th century.

In An American Vision: Three Generations of Wyeth Art, James H. Duff, director of the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, wrote “He (Pyle) told his students they must be artists first, and then illustrators, but aside from the composition, drawing and painting techniques he taught, he constantly emphasized drama and emotional content, which he believed had to arise from the artist’s personal concern for a subject. Composition could strengthen drama, but only if personal commitment and knowledge accompanied it.”

Pyle biographer Henry C. Pitz echoed this: “He seldom talked about technique to his students, lest they should fall in love with their own skills. He talked to them of the transforming power of the imagination, of immersion in the emotions of their pictorial themes and the necessity of feeling a oneness with the world of their subject.”

Harvey Dunn, a brilliant artist who grew up on a prairie homestead in South Dakota and later became an important teacher in his own light, put it with typical Midwestern directness: “Howard Pyle did not teach art. Art cannot be taught, any more than life can be taught . . . His main purpose was to quicken our souls that we might render service to the majesty of simple things.”

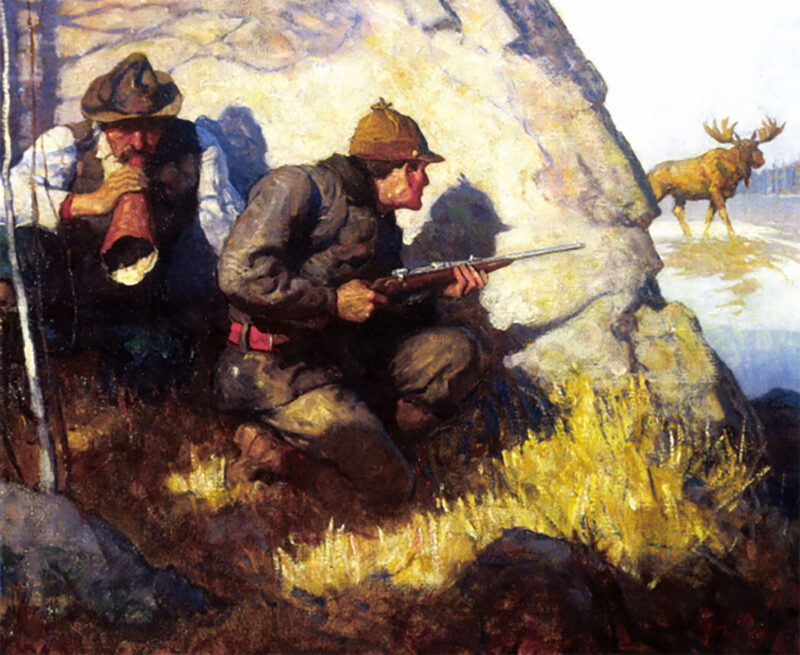

N.C. Wyeth conveyed the intense drama of a wilderness hunt

in his c. 1920 oil, The Moose Call. (Detail)

In 1898 Pyle began supplementing his classes at Drexel with a summer academy in Chadds Ford, a bucolic village on the Brandywine River; then, in 1900 he resigned from Drexel and opened his own school in Wilmington. The Pyle School lasted only until 1905 (the last summer session at Chadds Ford was held in 1903), but Pyle himself continued to lecture regularly and advise aspiring artists on a semi-formal basis until he departed for Italy in 1910. It was during this period that a bona fide art “colony” assembled itself around Pyle. The revered sportsman-artist William Hamden Foster, author of the classic New England Grouse Shooting, was among the many young talents who gravitated to Wilmington then.

Over time, Pyle, his students, and their aesthetic descendants began to be referred to collectively as “The Brandywine Artists.” The term “Brandywine School,” in him, was coined to include both the artists themselves — i.e., the school’s “members” — and the style of American realism they represented, a style that achieved its apotheosis, in the estimation of most critics, in the work of a “second generation” Brandywine artist, Andrew Wyeth.

Although few of the Brandywine artists specialized in depictions of hunting, fishing and the outdoor life to the exclusion of other subject matter — Philip Goodwin probably came closest to fitting this description — many of them did such scenes from time-to-time in the “normal” course of their careers. Field sports played a more prominent role on the stage of American popular culture, and in addition to the major outdoor magazines, the leading “general interest” periodicals — Scribner’s, Harper’s, Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post, etc. — frequently carried stories devoted to sporting themes. The example of Teddy Roosevelt, who credited his robust constitution to the many days he’d spent hiding, hunting and camping under the stars, helped popularize these pursuits.

N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), the fountainhead of the Wyeth family’s artistic “dynasty,” was easily the most acclaimed of Howard Pyle’s disciples. Indeed, many would rank him as the greatest of all American illustrators. Wyeth grew up on a farm on the outskirts of Needham, Massachusetts (now a suburb of Boston); recalling his life there in a 1942 letter, he wrote “Our relaxations were vigorous out-of-door sports and much time was spent hunting, fishing, sailing, etc. In some undefinable way our parents made us feel the romance of everyday living . . ..”

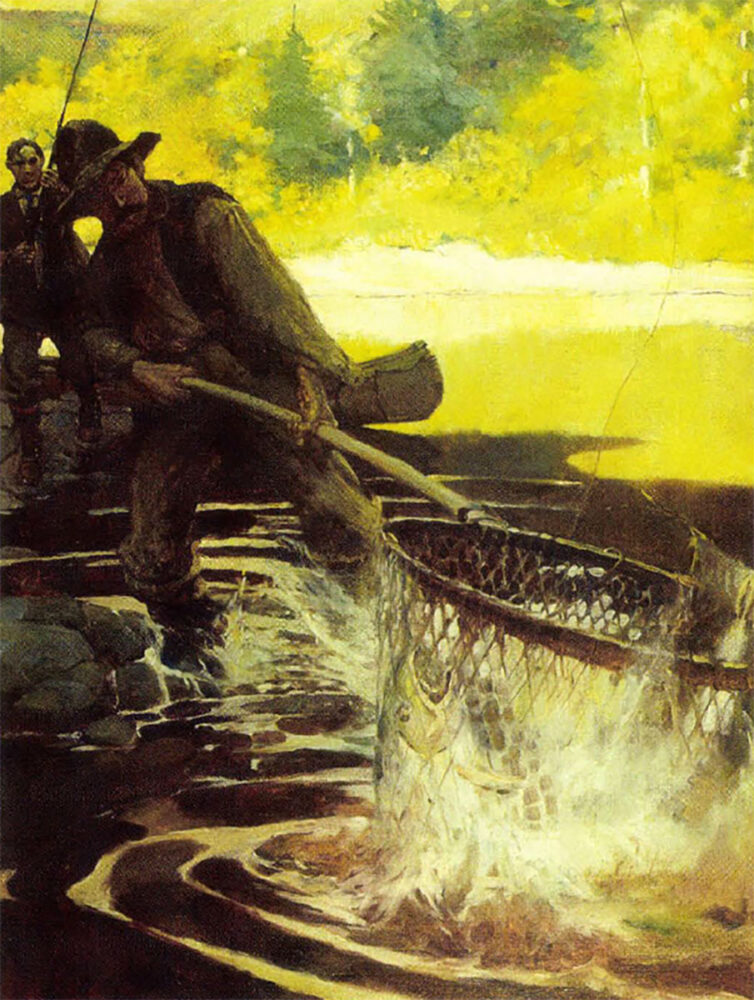

Frank Schoonover painted Landing Salmon in 1905 for Henry Van Dyke’s classic, Days Off.

This romantic bent was intensified by his enthusiasm for the work of Longfellow and Thoreau, both of whom had been close friends of Wyeth’s maternal grandparents. He began studying with Pyle in 1902, and his first published illustration, a bucking bronco and rider, appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in 1903. Early in his career he gained a reputation as a “Western” artist, but with his wondrously evocative illustrations for Treasure Island in 1911 and Kidnapped in 1913, he broke free of all labels to set a new standard of painterly excellence. As his son Andrew remarked, “Pa lifted illustration into something it had never been before.”

N.C. Wyeth was so taken “with the Brandywine River Valley when he went there to study with Pyle that he settled in Chadds Ford and called it home for the rest of his life — further rooting the “Brandywine tradition” in its native soil. He died there on October 19, 1945, along with a grandson, Newell, when the car he was driving was struck by a train.

Frank Schoonover (1877-1972) was preparing to become a minister when a newspaper announcement for Pyle’s illustration course at the Drexel Institute in 1896 piqued his curiosity — and changed the course of his life. Schoonover continued to study with Pyle when the latter let Drexel to found his own school in Wilmington, and over the years their relationship became almost like that of a father and son. In 1903 Pyle urged Schoonover to fulfill his dream of exploring the Canadian subarctic in winter; these adventures, including a dogsled crossing of Hudson’s Bay, inspired a pair of illustrated articles for Scribner’s, “The Edge of the Wilderness” and “Breaking Trail,” that jump-started his career. Schoonover’s Canadian experiences also proved invaluable when he was commissioned to illustrate Jack London’s White Fang. Schoonover’s reputation, however, is based on his Western subjects. He was the first to depict Hopalong Cassidy, and in the 1920s his illustrations accompanied a number of Zane Grey books and serializations. Unlike most of his contemporaries, who sent their canvases off to be reproduced with little regard for their ultimate fate, Schoonover insisted that his work — some two thousand images — be returned to him. As a result, the pictorial record of his career is much more complete than it is for other Brandywine artists. Schoonover continued to paint in his Wilmington studio until 1968 and died four years later at the ripe old age of 95.

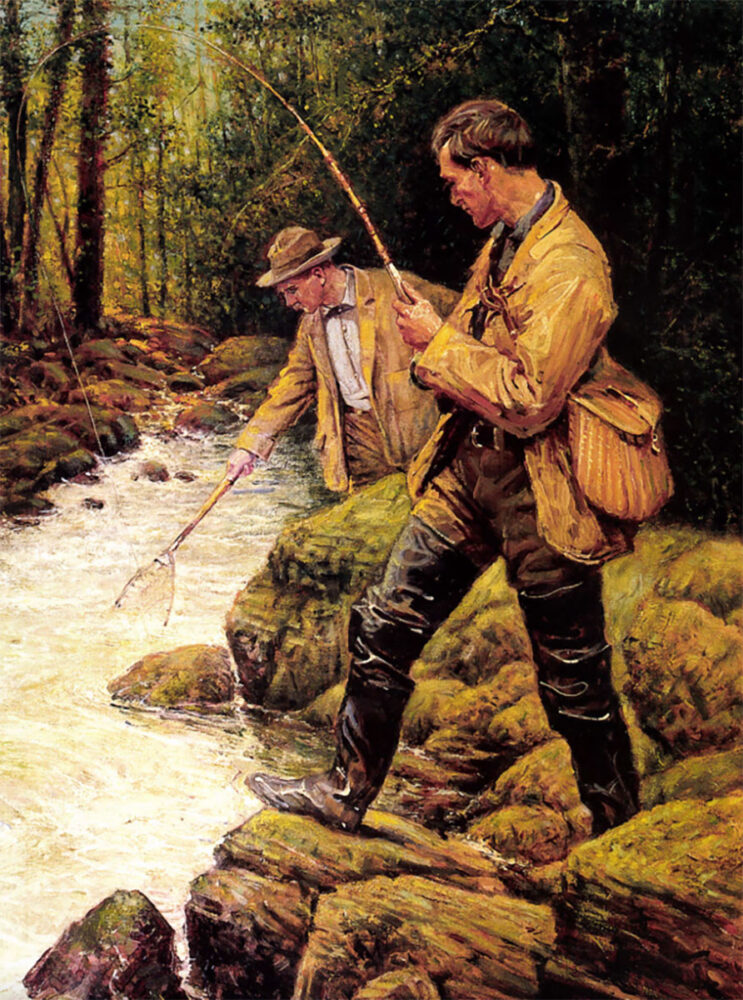

In 1919 Philip Goodwin (1882-1935) created one of the most recognizable corporate logos in the sporting industry: the Winchester “horse and rider.” Goodwin was just 17 when he began studying with Pyle; by age 22 he had his own studio in New York City. Goodwin was a skilled and ardent outdoorsman who spent extended periods of time in Maine, Canada and the American West (where he was frequently the guest of Western artist Charlie Russell), and his days with rod and gun, the latter in particular, served him well. In addition to regular magazine assignments, he did numerous calendars for such companies as Winchester Western, Peters, Marlin, DuPont and Harrington & Richardson. Goodwin also illustrated the rust edition of The Call of the Wild by Jack London.

Frank Schoonover lived to age 95, creating over 2,000 paintings during his career, among them His First Buffalo Hunt for the 1979 book Rising Wolf – The White Blackfoot by James Willard Schultz.

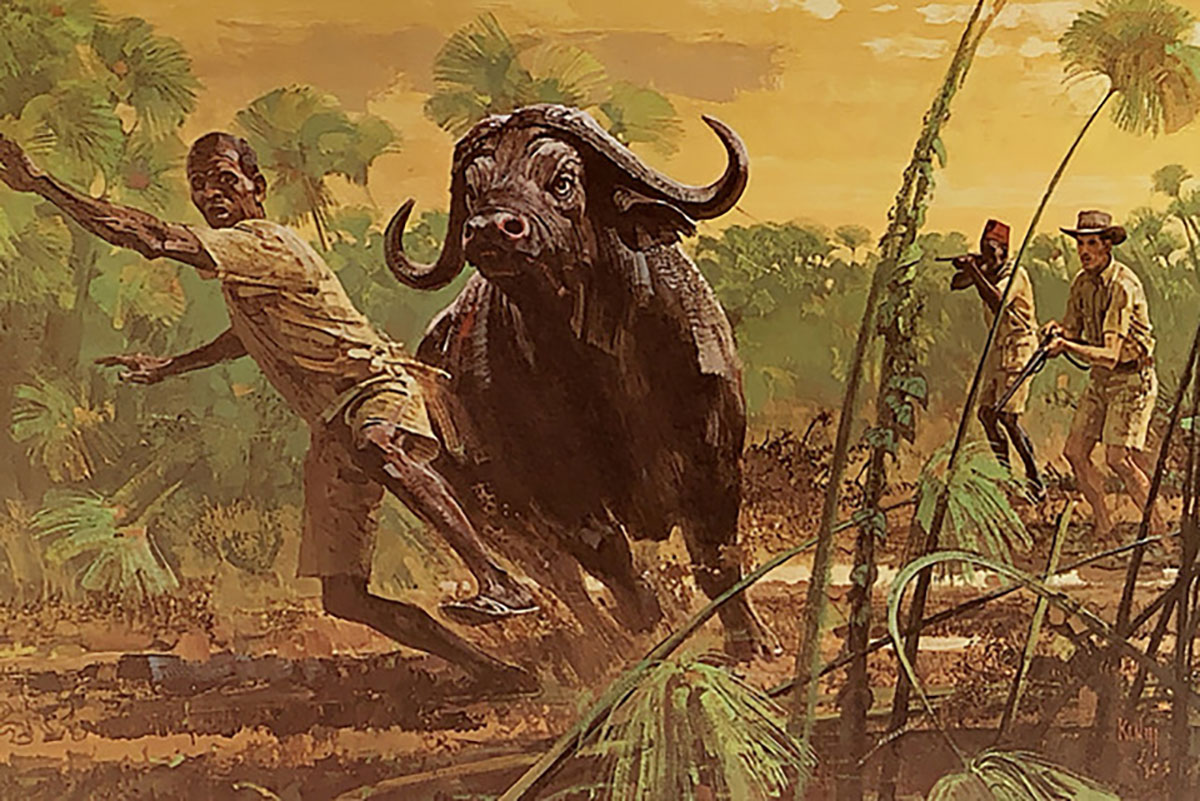

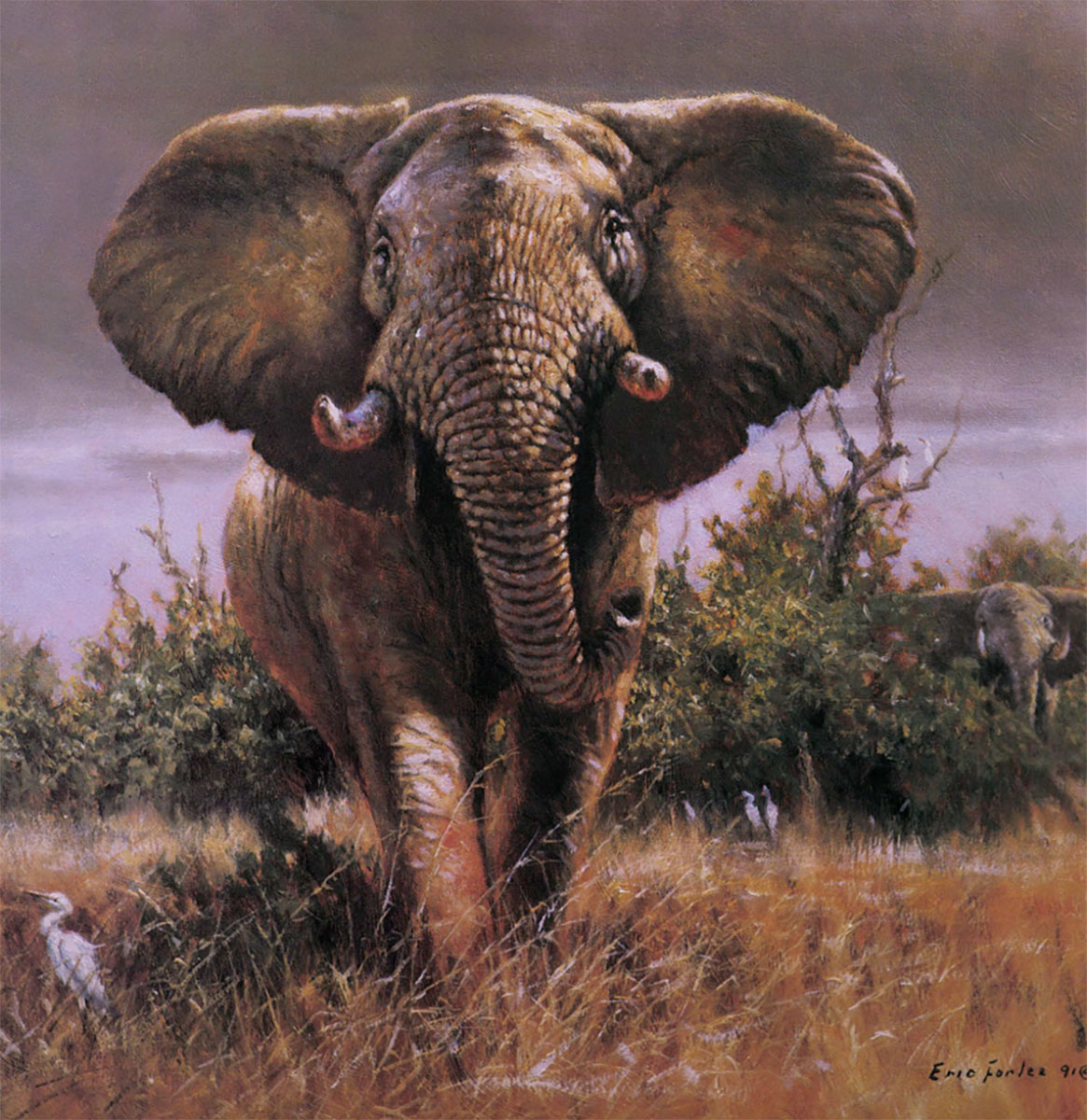

Somewhat ironically, the work for which Goodwin received the greatest acclaim during his lifetime was the group of illustrations he did for Teddy Roosevelt’s African Game Trails. The ironic part is that Goodwin’s depictions were based not on first-hand experience, as so many of his other illustrations were, but on Roosevelt’s animated accounts of charging lions, elephants and the like.

Goodwin was unique among the Brandywine artists in that virtually all of his work revolved around field sports, wildlife and the outdoors. He even did a few animals in bronze, exquisite miniatures that are now keenly sought-after by collectors. A lifelong bachelor, Goodwin died at age 54 in 1935, shortly after being stricken in his Mamaroneck, New York, studio.

At the time of his death, Oliver Kemp (1887-1934) was said to have painted more covers for the Saturday Evening Post than any other artist — or so he claimed, anyway. A native of Trenton, New Jersey — where for a time he was the director of the School of Industrial Arts — Kemp attended Pyle’s weekly lectures from 1905-1907, when Pyle was no longer teaching full time. This stint in Wilmington, however, was little more than a stop along the way for Kemp, who seems to have been a restless soul with more than a touch of wanderlust.

In addition to Pyle, Kemp studied with James Whistler, John Singer Sargent, William Merritt Chase and Jean-Leon Gerome. Just prior to World War I, he was shipwrecked in the Caribbean and spent five days adrift in a small boat under the broiling tropical sun (without food and water, it goes without saying); then, when war broke out, Kemp enlisted with the Allies, rising to the rank of Major by the Armistice was signed. The New York Times described Kemp as “a soldier of fortune during the World War period,” leading one to speculate as to exactly what the terms of his military service were — and under what flag he served them.

A regular contributor to Harper’s for many years, Howard E. Smith painted this scene of three young bird-hunters for the cover of the magazine’s April 1909 issue.

Published accounts indicate that Kemp traveled in Europe, Africa and the American West and that he “summered” in Bowerbank, Maine. So it seems a bit incongruous that when he died, in late summer 1934, he was living in an apartment in East Lansing, Michigan.

Howard E. Smith (1885-1970) was another relative latecomer to Howard Pyle’s party, attending the Wilmington lectures in 1907 and 1908. Smith moved from there to the Boston School of Fine Arts, where he studied under Edmund Tarbell. Indeed, from a stylistic perspective most art historians place him more squarely in the “Boston School,” which was a branch of American Impressionism, than in the more realistic tradition of the Brandywine School.

Be that as it may, Smith was a regular contributor to Harper’s for many years, and in 1914 took a teaching position at the Rhode Island School of Design. He won a number of prestigious awards during his career, including several from the National Academy of Design and in addition to painting, he was a gifted graphic artist, working briefly in lithography. Smith’s interest in equine art — he painted a portrait of Man-o-War, among other legendary champions — led critics to dub him “the Munnings of America,” Alfred J. Munnings being the renowned English equine artist who had the distinction of serving as president of the Royal Academy.

In his later years, Smith spent much of his time in Carmel, California, where he continued to exhibit his paintings and lithographs. An associate member of the National Academy since 1921, he was finally elected a full Academician in 1969, just a year before his death.

Philip R. Goodwin’s Morning Hatch.

Frank Stick (1884-1966) sold his first illustration, to Sports Afield, in 1903 — five years before he arrived in Wilmington and became part of the “colony” there, sharing a studio with Harvey Dunn. Stick illustrated and co-authored what is considered the first book on surf fishing, The Call of the Surf; he also illustrated several of Zane Grey’s fishing books and fished with Grey on numerous occasions. Scenes of fishing, hunting and “outdoor adventure” were Stick’s stock-in-trade, and he painted prolifically until the late-1920s, when he suddenly put away his brushes and didn’t pick them up again until 1942. In the 1950s, Stick did a monumental series of watercolors depicting over 300 fresh and saltwater fish indigenous to the East Coast.

Stick was active in conservation efforts around his adopted home of North Carolina, including the drive to create Roanoke Island National Park and Cape Hatteras National Seashore. The Outer Banks Historical Center in Cape Hatteras has over 300 Stick originals in its collection, along with a trove of materials donated by Stick’s son, David, a noted maritime historian.

Certainly, there were other Brandywine artists who tried their hands at sporting art from time to time, among them Douglas Duer (1887-1964) and William H.D. Koemer (1878-1938). But these six — Wyeth, Schoonover, Goodwin, Kemp, Smith and Stick — were the standouts, the cream of Howard Pyle’s exceptional crop. Their romantic images of the outdoors are, if anything, more compelling today than they were when the paint was still wet. They remind us of how it was, and they inspire us to discover — and to protect those few wild, unspoiled places where it continues to be.

Editor‘s Note: Special thanks to avid Sporting Classics reader James K. Kaiser, who was the catalyst for this article and who provided several key images. We are also indebted to John Schoonover, for information about the artists and for photographs of their work, and to John F. Apgar, who once again dug deep into the photo archives at J. N. Bartfield Galleries so we could share these exciting images with our readers.

Frank Benson’s Hunting & Fishing Art celebrates the sporting intaglio prints that mark Benson as the master of the sporting print. Over his lifetime, Benson produced over two thousand oils, watercolors, ink washes, and intaglio prints. He was exhibited in museums and galleries, was granted academic honors, and earned so many awards he became known as America’s most medaled painter. But intaglio printmaking stands as his unequaled, singular achievement in a career replete with great achievements. Benson is credited with developing in America the genre of sporting art and distinguishing himself as the dean of American etchers. Buy Now

Frank Benson’s Hunting & Fishing Art celebrates the sporting intaglio prints that mark Benson as the master of the sporting print. Over his lifetime, Benson produced over two thousand oils, watercolors, ink washes, and intaglio prints. He was exhibited in museums and galleries, was granted academic honors, and earned so many awards he became known as America’s most medaled painter. But intaglio printmaking stands as his unequaled, singular achievement in a career replete with great achievements. Benson is credited with developing in America the genre of sporting art and distinguishing himself as the dean of American etchers. Buy Now