It was not a conscious choice, but it seems that I have been building a collection. It is a collection of trout rivers.

The collection was started almost 50 years ago, the summer our family rented a cedar shingle cottage on a small Michigan lake. Lily pads filled its shallows, drifting and capsizing in a hot wind that smelled of orchards and cornfields. Locusts were shrill in the trees.

Bass drifted under the tepid mirror of the lake. Its surface was marred with the restless hunting of dragon flies. My father fished it regularly.

Sometimes it was dark when we heard his oarlocks coming back, and I often met him at the dock with a coal-oil lantern, to applaud his dripping stringer of fish.

It still seems impossibly perfect. Memories of swimming and sleeping on the porch are mixed with fishing off the dock for pumpkin seeds and perch. Crickets and whippoorwills sang at twilight. The rough wool Army blankets were often wet with dew in the mornings. It was a lazy summer when my parents were still young, and they had saved to buy a pale blue Oldsmobile in spite of the Great Depression.

Nearby was a little river near the lake. Its swift currents flowed over clean gravel, completely unlike the sluggish silt-colored rivers farther south. It was cold and glittering and alive.

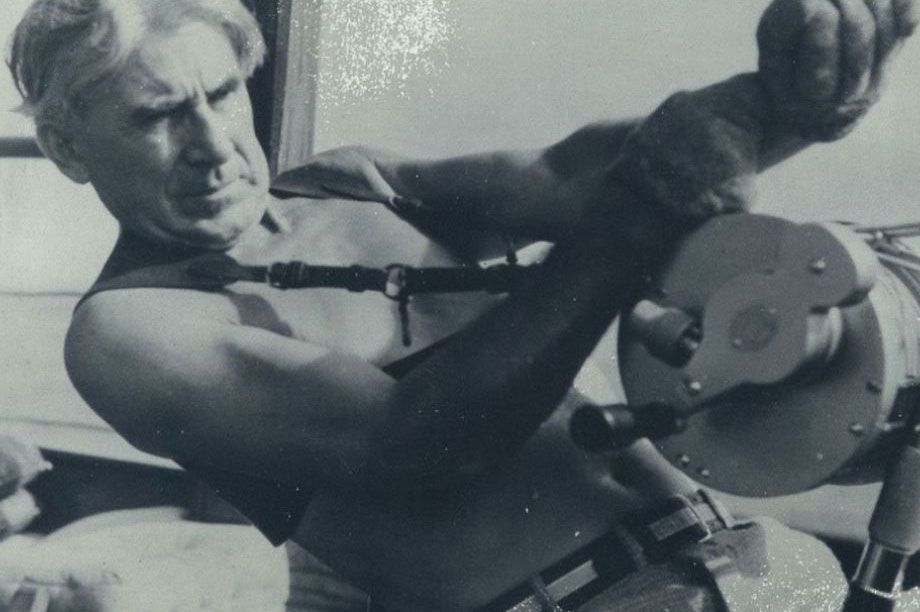

On the Aspetuck by Robert K. Abbett

One morning I stood on the bridge to watch an angler casting his flies. Swarms of mating mayflies were dancing over the riffles, and his casting was a patient choreography under the trees. The angler hooked and caught a small trout, and I scrambled down the bank to see it. Perch and pumpkin seeds were suddenly less exciting. That brook trout had a quicksilver poetry that I had never seen before.

Trout fishing seemed filled with magic.

The fish themselves were beautiful and exciting. The brook trout we caught were like jewelry trays of opal and moonstones and rubies, hiding in their cedar thickets and springholes. Rainbows were bigger and brightly painted, filled with a mixture of strength and explosive grace. Our western cutthroats mixed counterpoints of scarlet and bright yellow, darting in the pea-gravel riffles of the high country. Brown trout were a subtler breed, their plumage more like the solemn palette of a woodcock than the gaudiness of pheasants.

My first fly-caught trout took a wet Cahill on the Pere Marquette in Michigan, and its rivers were my boyhood tutors. Michigan is alive with rivers worth exploring. My first dry-fly fish was taken on the Little Manistee, near the logging host camp called Peacock. Others were caught in tributaries of the Pere Marquette, like the Baldwin and Middle Branchand Little South. There were day trips with picnic baskets to fish brook trout on the Pine, and still other summer trips were taken to rivers farther north, rivers like the Bear and Boardman and Platte. The queen of those Michigan rivers is still the AuSable, with its several branches, flowing through labyrinths of pines and cedar sweepers. Sometimes we traveled to the Pigeon and Sturgeon and Black, streams that Hemingway fished from his family’s cottage on Walloon Lake. He loved the Sturgeon so much that he was late for his wedding at the tiny Methodist church in Horton’s Bay.

Before my college years were finished, we took trips into the Upper Peninsula, taking the Mackinac ferries across the straits to fish the Driggs and Ontanagon and Laughing Whitefish. One teenage summer I hiked from Seney, and still found marsh marigolds blooming along the swampy little Fox. Our last expedition included a canoe trip on the Tahguamenon, and we explored the stone-covered beaches where the Big Two-Hearted River winds sluggishly into Lake Superior.

Wisconsin is pike and muskellunge country in most people’s minds, but it also has its share of trout streams. There were pleasant days along the Prairie and Name kagon and Wolf, and float trips through the lovely brook trout bogans in the headwaters of the Brule, where Coolidge and Hoover and Eisenhower were fishing guests at Cedar Island.

Because my mother’s family were ranchers, and her sisters all married ranchers, there were boyhood trips each summer into the mountains of Colorado and Wyoming too.

My first memories of Colorado are the steep, switch-backing loop of Berthoud Pass to Hot Sulphur Springs, where we fished in Byer’s Canyon and spent a morning on the Sheriff’s Ranch. We fished the 10,000-foot headwaters of the Arkansas too, from a family ranch under Mount Massive, across the valley from Malta Crossing. The Gunnison was still a free-flowing river in those years, and we fished it between the McCave Bridge and Sapinero, using the old Cooper Ranch a sour headquarters. Its currents were sweeping and strong, its channels braided across the fine, big country of cottonwoods and pinon mesas and foothills. Sapinero and the other landmarks lie drowned under the Blue Mesa reservoir today, and two high concrete dams have filled its Black Canyon downstream, entombing one of the most remarkable gorges in the world.

There were weeks along the Frying Pan at Ruedi, and on the Roaring Fork at Aspen, with its curious checkerboard bottom of alabaster and blood-colored basal. The Ruedi mileage of the Frying Pan, perhaps the finest public water in western Colorado, is also buried under a reservoir built to water cantaloupes and lawns between Denver and Rocky Ford. The startlingly clear little Crystal is a poem, spilling past the ghost town marble quarries in its headwaters above Redstone. There were other Colorado rivers in those years, like the Elk and Little Snake, where a happy winter was spent by Jeremiah Johnson and his Indian wife.

Wyoming came later, when I was finishing my college years and living in Colorado. There were fine days along the North Platte and Encampment, and river floats from Dead Man’s Barand Schwabacher’s Landing on the Big Snake. Jackson Hole is alive with pretty little spring creeks worth knowing, and there are no other mountains quite like the Tetons. It is impossible to count the hours spent stalking big cutthroats in the weedy currents of Blue Crane, Flat, Spring, Fish, and Blacktail spring creeks, where I once caught an eight-pound rainbow on a small wet fly. There were big dry-fly cutthroats on the lower Gros Ventre, but irrigation has decimated that mileage, and we fished the Green with George Kelly at Fontenelle in October, hoping to hook an alligator-size brown. It is a country of empty spaces and horizons, strangely beautiful and rich in history.

Wyoming came later, when I was finishing my college years and living in Colorado. There were fine days along the North Platte and Encampment, and river floats from Dead Man’s Barand Schwabacher’s Landing on the Big Snake. Jackson Hole is alive with pretty little spring creeks worth knowing, and there are no other mountains quite like the Tetons. It is impossible to count the hours spent stalking big cutthroats in the weedy currents of Blue Crane, Flat, Spring, Fish, and Blacktail spring creeks, where I once caught an eight-pound rainbow on a small wet fly. There were big dry-fly cutthroats on the lower Gros Ventre, but irrigation has decimated that mileage, and we fished the Green with George Kelly at Fontenelle in October, hoping to hook an alligator-size brown. It is a country of empty spaces and horizons, strangely beautiful and rich in history.

There are wagon cuts still visible in the sandstone river crossings of the Bridger Basin. The Mormon and Oregon trail crossings were there. High above the river, in the dry cheatgrass that crowns a sandstone bluff, lies the grave of an infant girl from the Whitman party.

Not all of the echoes are tragic. Forty-rod Creek is a swift spring-fed tributary of the Green, and it meets the river not far from the prairie benches where frontiersmen like Jedediah Strong Smith and Jim Bridger and Joseph Reddeford Walker held their trapper’s rendezvous in 1833.

Yellowstone lies a hundred miles north.

It is a wellspring of major rivers worth collecting. Its volcanic plateaus and outcroppings and fissures pulse with both cold and boiling-hot aquifers. The Missouri and Yellowstone and Snake are all born in the Yellowstone country. Its fisheries have been managed with a unique sense of husbandry, which ended hatchery plantings and sharply limited killing, and they offer sport comparable to the fishing described in the journals of the first military expeditions into the region.

The Yellowstone itself teems with trout. Its free-rising cutthroats are particularly plentiful at Buffalo Ford, and in the headwater meadows above Yellowstone Lake, in the basin at Thoroughfare Creek. Other excellent fisheries include the upper Lamar, Pelican Creek, and the high Absaroka meadows of Slough Creek. It winds across pristine meadows the color of a freshly made broom, and it is still possible to find the tracks of a grizzly in the silt, water still oozing in the claws.

The headwaters of the Snake hold cutthroats too, where it drains the marshy bottoms at Two Ocean Pass. Its principal tributary is the Lewis, with Lewis and Shoshone lakes in its headwaters. It held no fish when the Yellowstone was first discovered, and it was planted with a Scottish subspecies of brown trout shortly before the First World War. It has since evolved into a superb fishery, particularly in the fall, when the fish are migrating into its Lewis meadows and Shoshone Channel. The little Gibbon, and the bigger Madison, are both excellent brown-trout water too. Both rivers receive the fertile discharges of hot springs and geyser basins, making them weedy and rich in fly-life. There are happy memories in my collection of the Gibbon meadows at twilight, the flats across the Elk Meadows downstream, the water at the Talus Slides, the spring-chilled ledge at Nine-Mile Hole, otters playing in the weedy channels at Slow Bend, and prospecting for migrating fish at the pools called Behind-the-Barns.

The Firehole is the strangest trout stream on earth. It was the inspiration for one of Jim Bridger’s favorite yams, about a river that flowed so fast it got hot enough to cook its trout.

Fall Fishing on the Shepaug by Robert K. Abbett

Its world is a watershed filled with erupting hot springs and boiling lakes and geysers that saved Bridger from his own exaggerations. It was also fishless when the Yellowstone was first discovered, and its stockings have evolved into another excellent fishery. Its fly-hatches and lovely meadows have transformed the Firehole into a mecca for anglers who like sophisticated trout. The long flats below Nez Perce Creek are called the Broads of the Firehole and the Fountain Flats lie upstream, reaching to Sentinel Creek. Ojo Caliente Spring and Fairy Creek Pool are next, along with the Feather Lake bottoms and Elk Springs. Midway Geyser Basin has scalding springs that cascade wildly into the river, spilling discharges that billow with steam on cold October mornings, and could easily boil the trout. Muleshoe Bend and the Iron Bridge are still farther upstream, and in the lodgepole meadows at Biscuit Basin, the Firehole winds like a careless necklace through the trees. The Little Firehole and Iron Creek are between Biscuit Basin and Old Faithful, and their snow-melt secrets are worth knowing in particularly hot summers. Old Faithful still performs hourly, and its sister geysers are a cauldron of steaming water that affects the ecology of the entire river. Its bottoms are alive with elk and buffalo, crossing the river in its first October snows, their shaggy coats steaming in the cold.

Jack Hemingway and I sprawled in the noonday grass along the Firehole in a perfect October sun. ”You know what’s wrong with this river?” he asked wryly, pouring a few last swallows of Corbieres. “We don’t own it!”

Our eastern mountains still keep secrets worth collecting, from the Allagash in northern Maine to the Cane and Chattooga in the Carolinas.

The Raritan and Flat Brook and Musconetcong were neighbors in the last college years at Princeton, and I still fish them like old friends. Letort Spring Run is a challenging puzzle, along with Falling Springs, in the Appalachian drainages of the Potomac and Susquehanna. Other famous streams drain the Allegheny forests. Spruce Run and Young Woman’s Creek offer lovely water. Rivers like the Broken straw and Kettle and Big Fishing are classics, and the Loyalsock was home water to John Alden Knight.

The gentle Brodheads has been my home river these past 25 years, and its pools are hung with ledges and hemlocks and laurel. Like the Catskill rivers farther north, the Brodheads has its echoes of great anglers like Thadeus Norris and Edward Ringwood Hewitt and George la Branche.

George Inness and Thomas Cole were painters who also loved our eastern mountains, and their landscapes introduced the Catskills to the world. It was a pastoral world of huge Dutch plantations along the Hudson, which reached the sea at New Amsterdam.

Catskill rivers are the shrines of American trout fishing, and each still has its major figures. Art Flick still lives in the Schoharie country, although his charming West Kill Tavern was lost in a tragic fire. The Folkert brothers operated a store at Phoenicia, and it has become the shrine on the Esopus, with ‘Paul O’Neill as its poet laureate. Walter Dette is still the Dean of the Beaverkill, perhaps the most famous trout stream in America. His lifelong rival was the celebrated Harry Darbee, who died just before Christmas, after many years in a tackle-filled house above the Willowemoc. Reuben Cross worked his alchemy with fur, feathers and steel in his farmhouse above Beaverkill Post Office 50 years ago. Theodore Gordon spent the last years of his life at the Knight farm on the Neversink, lonely and frail and dying of tuberculosis, dressing fly orders in yellow lamplight.

Adirondack country lies beyond Albany, and its mountains are drained by several important rivers. Thirty years ago, I fished them regularly and I still fish them often in my mind. The Bouquet and East Branch of the Ausable both rise between Mount Marcy and Lake Champlain. The old boarding house on the East Branch at Upper Jay is gone,where the register held the names of Richard Carley Hunt, Corey Ford, Dana Storrs Lamb, Guy Jenkins, Ted Townsend, and Ray Bergman. The Saranac and Big Chazy and Oswegatchie were brook-trout rivers then, and the tumbling West Branch of the Ausable is still a kettledrum-and-cymbal river of fast, broken rapids that you like best before you reach 35. It rises in surprisingly wild country, like the storied Hudson itself, little changed since Winslow Homer painted his fly-fishing watercolors in the stillness at Mink Pond.

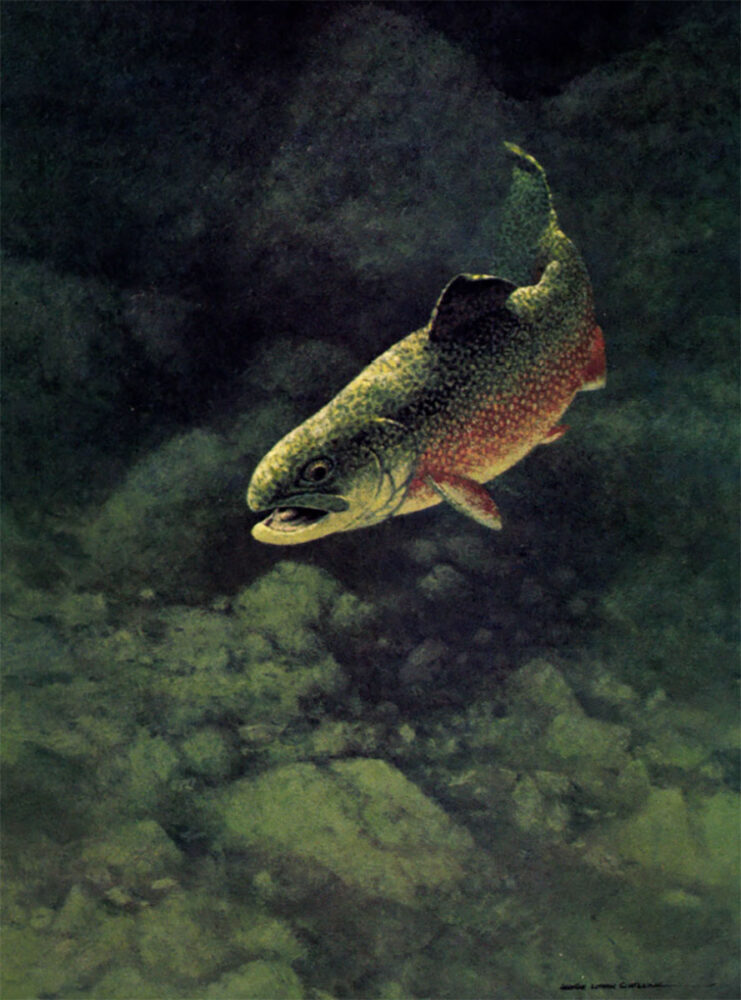

Brook Trout by George Luther Schelling

Lee Wulff lives in the Catskills today, where he operates a fishing school on the upper Beaver kill, but thirty-five years ago he lived on the Batten kill at Shushan Post Office. It is still a sweeping river, hurrying to join the Hudson, and I fished its famous pools from the Covered Bridge to the Dutchman’s Hole. The river rises in Vermont, and it was home water to the painter, John Antherton. Fishing it from the Arlington Inn, its fluted Doric portico like an archetype of New England lodgings, is a pleasant pastime mixed with fine cuisine and comfort. The stretch downstream at Benedict’s Crossing is fine water, and was celebrated in one of the last watercolors painted by the late Ogden Pleissner.

Other western odysseys have taken me farther afield in recent years, on the famous rivers of Idaho and Montana, and to several famous steelhead rivers along the Pacific Coast.

Silver Creek at Sun Valley has become a favorite river, a strange British chalk stream rising from giant springheads in the Idaho desert. The Big Lost and Little Lost rivers gather in the Copper Basin, only to plunge underground in the lava badlands north of Craters of the Moon. The Teton has survived the failure of its ill-planned dam, and it is still a superb cutthroat fishery draining the western face of the Tetons. The Clearwater and Kelly are jewels in northern Idaho, but the incomparable Henry’s Fork of the Snake is its crown. Its smooth currents and fly-rich shallows make it perhaps the finest dry-fly river on earth, but its trout are sophisticated and spoiled.

Most trout fishing is like checkers. Rene Harrop is its best-known fly maker. But our Henry’s Fork trout play chess.

Montana is a spectacular collection of rivers. Livingston is its mecca, with the Yellowstone itself and its famous spring creeks, and the old railroad hotel at Chico Hot Springs. The Madison is justly famous, and I have floated it many times in salmon fly time, with old friends like Greg Lilly and Mike Lawson at the oars. Other years I have fished the Beaverhead and Big Hole with Philip Wright, mixing their float-trip country with gourmet lunches served on checkered tablecloths. Terry Ross and George Kelly are old friends after many years on many rivers, and I remember a recent float with George Anderson on the Yellowstone below Gardiner.

Anderson guessed right that morning, putting in above Yankee Jim Canyon, and we found the big Pteronarcys flies hatching. Salmon flies had been coming for several days farther downstream at Emigrant and Pray, and the crowds were fishing there. We congratulated ourselves and caught fish steadily, thinking we were the only boat fishing upstream, but we were wrong.

Russell Chatham was working his big MacKenzie boat skillfully, and his fishing partner stood casting a tightly controlled loop. Chatham is a painter, and has landscapes of the Yellowstone country in several well-known collections. “How’ re you guys doing?” Chatham shouted.

“Pretty good,” I yelled back. When his fishing partner turned downstream, it was Thomas McGuane, the writer whose work includes films like Ninety-Two in the Shade and The Missouri Breaks. Both men are neighbors near Livingston.

“Let’s try to meet for lunch,” McGuane yelled. “We can talk about things like love, death and literature.”

“I’m lousy about small talk,” I shouted back.

The Klamath and Eel are steelhead rivers in northern California, and I have come to love the little Gualalla, a lesser river on the spectacular coast just above San Francisco. The Rising and Fall and Hat are a series of outstanding spring creeks above Mount Lassen, and the McCloud is still an enchanted river in its forest headwaters.

Polly Rosborough showed me his secret places on the Williamson, and the pretty spring creeks at Chiloquin and Fort Klamath. It is colorful country just below Crater Lake, and it has an equally colorful history. It was the stamping grounds of Captain Jack, the infamous tribal leader who triggered the bloody little Modoc War.

Oregon has other rivers worth collecting. The Metolius is a poem, with an inn called the House-on-the-Metolius, and it rises in a series of bone-chilling springs a few miles above Wizard Falls. The Deschutes is utterly different. It drains a world of wild desert canyons and towering cliffs of lndian pictographs. It has the finest runs of summer steelhead left on the Pacific Coast, and the last time I fished it was a September float with Ben Bachulis and Jock Fewel. The North Umpqua is forest river. Its ledge rock pools and chutes and wild rapids are filled with a fierce poetry, all emerald and spume. Over the years, I have shared it with friends like Frank Moore, Jack Hemingway, Jim Van Loan, Keith Stonebreaker, and Dan Callaghan. Its Steamboat Inn is a shrine to steelhead fishermen, and the North Umpqua was a favorite river of the writer Zane Grey.

Washington has its enchanting places, particularly in the lush rain forests of its Olympic Peninsula. Its rivers there are steelhead fisheries of sea-bright rainbows, rivers like the Quinault and Bogachiel and Hoh. The Kalama and Cowlitz and Skagit are winter-run rivers, and their sport is excellent when the steelhead are coming, but I particularly treasure my time on the Stillaguamish, with old-time steelhead legends like Ralph Wahl and Wesley Drain. Washington offers beautiful country, with a necklace of white-capped volcanoes, although its fishermen mourn the loss of the Toutle to the recent eruption of Mount Saint Helens.

But my collection has its tiny artifacts too, and I added one this past September on the little Rio Costilla in New Mexico.

Its headwaters are among the few places that still shelter pure strains of the Rio Grande cutthroat stocks. The fish are like precious stones, darkly spotted and burnished in vermilion and gold. The upper Costilla is a series of tiny bathtub-size pools and swift riffles, winding through high-country meadows of wildflowers. Its cutthroats are willing, quick to take the fly, and a nine-inch specimen is a trophy.

Tucker Dorn is a friend from San Antonio, and we had come to these high meadows in the Sangre de Cristo mountains to photograph and release a few of these rare trout.

We caught them almost too easily, and they were beautifully colored fish, but the unique collector’s item of the morning was a surprise. The dry fly that I was using had become so saturated that it refused to float, and I had left both flies and fly dressing in the jeep. It was warm that morning, and I sat cross-legged in the grass, nursing its soggy hackles.

We caught them almost too easily, and they were beautifully colored fish, but the unique collector’s item of the morning was a surprise. The dry fly that I was using had become so saturated that it refused to float, and I had left both flies and fly dressing in the jeep. It was warm that morning, and I sat cross-legged in the grass, nursing its soggy hackles.

Several feet away, in a patch of brightly colored harebells, a small bird hovered and sipped nectar. “Hummingbird,” I thought.

But it was not a hummingbird. Its wings were flushed with a startling rose and orange, and I crawled closer. It was a huge sphinx moth. Its wings were a humming bird blur, working from flower to flower.

This collection of 22 stories set on fabled waters from Alaska to Baja confirms Scott Sadil’s reputation as a writer of literary fiction in the best sporting tradition. Buy Now

This collection of 22 stories set on fabled waters from Alaska to Baja confirms Scott Sadil’s reputation as a writer of literary fiction in the best sporting tradition. Buy Now