The dogs struck in the old ricefield bottom, grown up now in a great snarl of water-trees, the bell-trunked tupelo, sweet gum and soft maple, the ground beneath a foot deep with the soggy litter from the last hurricane surge, driftwood snags and ricks of dead spartina cane from when the big blow breached the dunes. The swoosh of the surf and the gentle rumble of the waves spoke of a rising tide. The sun was a hand’s-width over the sea when we loosed the hounds.

Christmas in the Lowcountry of South Carolina. I’ve knocked around a bit, hunted the alphabet from Argentina to Zambia—birds, buffalo, bears, bison and boars—but there is no place I’d rather hunt than the land of my birth at Christmastime when this maritime forest finally throws color, a belated explosion of delight.

The last lonesome wild muscadines looping tattered, golden and forlorn here and there over black swamp-water, the pig nut hickory so yellow it hurts your eyes, the sweet gum, mottled yellow, green and brown, and always the holly, slick and evergreen, thorns on the leaves of the Pensacola’s, the smooth leaf yaupon in the understory, both lit up with berries as red as the blood we drew that day.

Long boned, big hearted, sad-eyed Walkers, the noblest of the hounds, fleet of foot, keen of nose. The lead dog struck, a-whoo, a solitary note, but not for long. His opinion was immediately seconded and then greeted with universal acclamation as the pack came howling through the flooded timber like swamp-ground haints, music to us who love

the bay.

But this wasn’t the buck’s first dance with these dogs. We’ve run these swamps for the past six years every Christmas. A nubbin, a spike, a fork-horn and now a full eight points, he was a veteran. I watched him come, ducking and weaving through the understory, brushy clump to brushy clump, his head low, slipping, slipping before the hounds. He reckoned the water would hide his scent but he left it all over the floating debris and the dogs were not fooled this time.

I was toting a classic Southern deer gun, a long-barreled Fox double 12-gauge, circa 1936. I put the bead on his shoulder and he toppled into an old ricefield quarter drain, level full of storm debris.

The hounds did their best, pushing muzzles and chests through the great wreckage. Erica got ahead of them on her gun horse, whooping encouragement.

I waved and hollered, “Leggy he’s down in that quarter drain!”

Six feet sock-footed and a great beauty, I call her Leggy. She calls me Boss.

The Marsh Tacky is a descendant of the Spanish war horses cast ashore in South Carolina five centuries before.

She reined in her mare, a Marsh Tacky grullo, the color of a chocolate milkshake, black dorsal stripe, black mane and tail, a descendant of the Spanish war horses cast ashore here five centuries before. Folks said a Tacky got you coming and going in the olden days, brought the midwife to your momma’s bed and when your time was done, a Tacky hauled your carcass to the burying ground.

The breed was nearly lost to John Deere and Henry Ford, but we brought them back, swamp savvy, gun broke now and forevermore. High-stepping through the litter, this Tacky beat the dogs to the kill.

“Nice job, Boss! A perfect eight!”

“Can you drag him out? I don’t think I could walk through that mess.”

She swung a long lariat with a long arm, deftly dropped the loop around the antlers on the first try. She dallied the rope at the saddle-horn, the mare leaned into the load and the buck came sliding through the hurricane waste, the hounds grinning, wagging and whining, padding along the easy walking left behind the buck.

Leggy dropped the lasso, swung from the saddle. She grabbed the front hooves, I grabbed the rear—one, two, three, heave—and the deer flopped into my pickup with a wheezy thud. “Merry Christmas, Boss,” she said.

A popcorn rattle echoed through the timber, three, four shots, then two more from farther back in the woods. Woman, mare and hounds took note. “Gotta run,” she said and galloped away, a long string of happy hounds in tow.

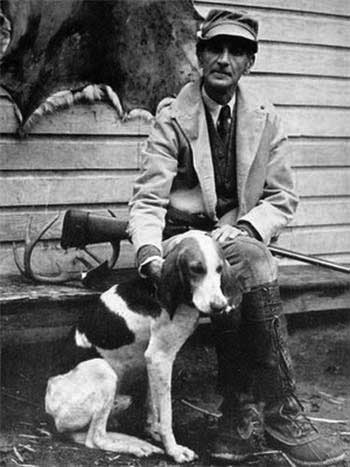

They called him Old Flintlock behind his back, from his ancient lineage, his impeccable manners, his unshakeable faith, his antique notions. Archibald Rutledge was staunch conservationist, the author of 50 books of prose and verse, the first Poet Laurate of South Carolina and folklore says he lost the Nobel to Faulkner by one vote. He was raised on Hampton Plantation along the South Santee River. His ancestors signed the Declaration, the Constitution, too. George Washington sat on his front porch and was pallbearer at his great grandmother’s funeral. Old Flintlock hunted deer with buckshot, horses and hounds every Christmas. He wrote about it and I read it. Art imitates life and life returns the favor.

They called him Old Flintlock behind his back, from his ancient lineage, his impeccable manners, his unshakeable faith, his antique notions. Archibald Rutledge was staunch conservationist, the author of 50 books of prose and verse, the first Poet Laurate of South Carolina and folklore says he lost the Nobel to Faulkner by one vote. He was raised on Hampton Plantation along the South Santee River. His ancestors signed the Declaration, the Constitution, too. George Washington sat on his front porch and was pallbearer at his great grandmother’s funeral. Old Flintlock hunted deer with buckshot, horses and hounds every Christmas. He wrote about it and I read it. Art imitates life and life returns the favor.

But to his face they called him Mister Archie or Uncle Archie even if you were only shirt-tail kin. I almost got to call him Uncle Archie myself when his older brother took an amorous interest in my widowed maternal grandmother. Not sure how they met, Chlotilde Rowell Martin and Thomas Pinckney Rutledge. She was a pick and shovel journalist and he was supervising the Civilian Conservation boys who were building cabins and campgrounds on Hunting Island State Park during the Great Depression. Perhaps she had an assignment to write about the work that led her to take her two teenaged children on an extended camping trip there in the summer of 1936. My uncle was the odd boy out, but as the only females on 5,000 acres, my mother and grandmother were centers of attention. Momma said there was one guitar and one boy who could play it and he only knew one song, which he played to distraction, a drearisome “I’m Dreaming Tonight of My Blue Eyes.” Momma’s eyes were blue.

I met up with Leggy and my other hunters in a meadow beneath the spreading live oaks. The horses and hounds were watered and tethered, a fire popped and crackled, the smoke rolled and the heat felt good. The deer had been quartered and all who wanted venison had iced down their share, when a veritable and impromptu feast was spread on tailgates and hoods. Smoked quail, deviled eggs, venison salami sandwiches, crisp pickles, chips—and as the guns were unloaded and cased—cold beer and lots of it.

The beer got me to thinking like it generally does. That romance between Chlotilde and Thomas was ultimately unsuccessful, for what reason I know not. But had it prospered, would she have followed him back to the Santee? Would I, or some variation upon myself, have hunted Hampton with my Uncle Archie, Old Flintlock? Idle speculation is the sweetest kind but it is still idle. But I do get up to the plantation from time to time and sit on the porch where Old Flintlock sat, where Washington sat.

And I still hunt deer every Christmas.