A well-directed common leaden bullet is sufficient to make the biggest rhinoceros bite the dust; but for a long range, say a hundred yards, two-thirds lead and one-third solder is best, or, better still, all spelter. The head of the rhinoceros is so thick, that there is little use in firing at it; and, if it should be penetrated, it is a great chance that the bullet finds the animal’s brain, as it is very, small and confined in a chamber about six inches long by four high. Sparrman relates that, on filling this receptacle with peas, it was found to hold barely a quart. He tried a human skull, and found that it comfortably accommodated nearly three pints.

Mr. Anderson’s experience in hunting the rhinoceros is of the most thrilling character. Although he slew scores of them from behind the “skarm,” his favorite mode was to “stalk” them. He tells of a monstrous white rhinoceros that nearly put an end to his stalking.

The spoor of the rhinoceros.

“Having got within a few paces of her,” says he, “I put a ball in her shoulder; but it nearly cost me dear ; for, guided by the flash of the gun, she rushed upon me with such fury, that I had only time to throw myself on my back, in which position I remained motionless. This saved my life; for, not observing me, she came to a sudden halt just as her feet were about to crush my body. She was so near me, that I felt the saliva from her mouth trickle on to my face. I was in an agony of suspense, though happily only for a moment; for, having impatiently sniffed the air, she wheeled about and made off at full speed.”

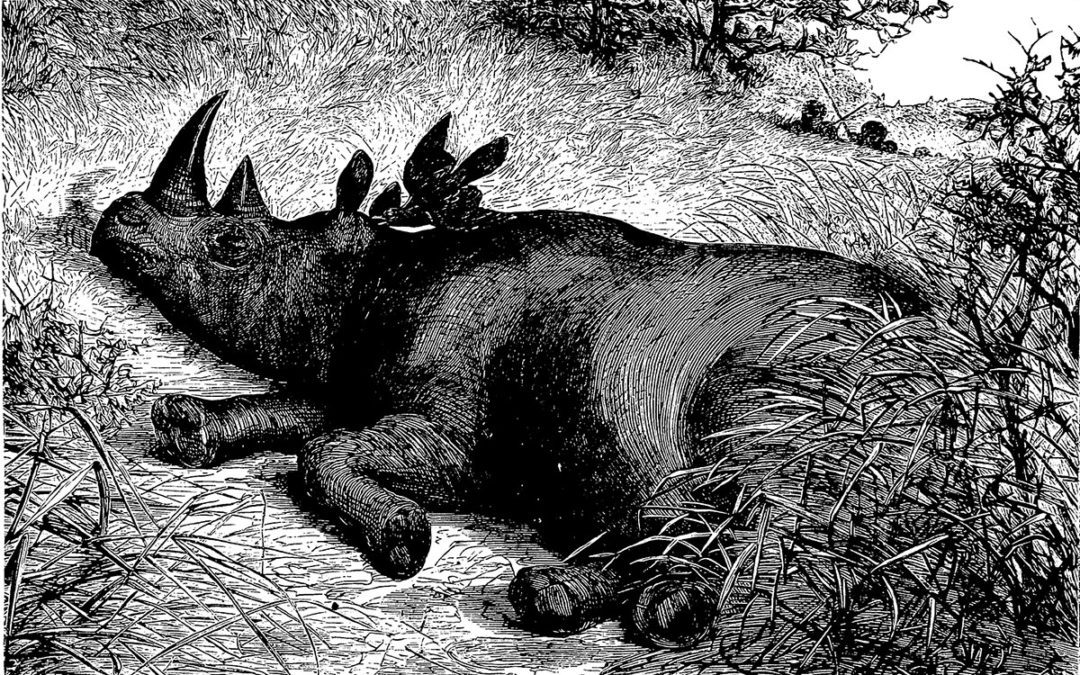

Some quadrupeds find a remarkable protection in the company of animals belonging not only to the same genus, but to a totally different class. Thus, the rhinoceros is frequently accompanied by a bird —Buphaga africana — that feasts upon the larvae that settle in his skin. As the range of his small and deep-set eyes is impeded by his horn, he can only see what is immediately before him, so that, if one be to leeward of him, it is not difficult to approach within a few paces. But the bird sees all the better, and flying away at the first approach of danger, awakens the short-sighted brute’s attention by a shrill cry of warning. Thus the insects which plague the rhinoceros become the indirect means of his preservation from many perils, as, but for them, his winged monitor would have no inducement to seek his company.

The African buffalo possesses a similar guardian in the Texior erythrorynchus. When the beast is quietly feeding, the bird may frequently be seen hopping on the ground, picking up food, or sitting on its back, and ridding it of the insects with which its skin is infested. The sight of the bird being much more acute than that of the buffalo, it is soon alarmed by the approach of any danger; and, when it flies up, the buffaloes instantly raise their heads to discover the cause which has led to the sudden flight of their companion.

The article originally appeared in The American magazine. v.1 1876 Jan-Jun.

“They all pledge to be back. So I believe that you mean what you say. But the odds are that you’ll never be back.”

“They all pledge to be back. So I believe that you mean what you say. But the odds are that you’ll never be back.”

Less accurate words have seldom been uttered than those of professional hunter Lew Games to client Mike Miller on safari number one after Mike promised to come back as soon, and as often, as he could. Far from being the usual one-and-done safarist, Mike is now making plans for safari number sixty-four!

Mike’s first sixty-three African safaris—including trips to Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, and Cameroon—form the basis for Facing the Charge. A gifted storyteller, writer Scott Longman makes Mike’s African stories come alive on these pages, describing in page-turning detail a tremendous range of experiences during which Mike and his colleagues faced charges from the Big Five—Cape buffalo, lion, leopard, elephant, and rhino—as well as from man-eating crocodiles, slithering pythons, vengeful baboons, and a hormonal Chevy Tahoe-sized mama hippo who had Mike squarely in her front-view mirror.

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria, and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa, and pays tribute to the men and women who have made Africa a second home for Mike.

In her foreword, Fiona Claire Capstick, widow of legendary professional hunter and author Peter Hathaway Capstick, captures the essence of Facing the Charge, calling it “the stuff of high drama and retrospective hilarity,” while also noting that it showcases the “innate skills and knowledge of the African trackers, without whom no African hunting safari would be possible.”

Facing the Charge will appeal to both seasoned African hunters and novices anticipating their first safari, as well as to anyone who enjoys adventure in exotic locations. Buy Now