“Brian Jarvi’s work excites me because he’s young and he commands the same qualities as you see in works by the old masters.”

As outdoors people, let us be blunt: It is a troubling, tough and harrowing time to be alive on Planet Earth, but especially if you are one of our iconic game animals having to navigate through the turbulence of human strife and political instability.

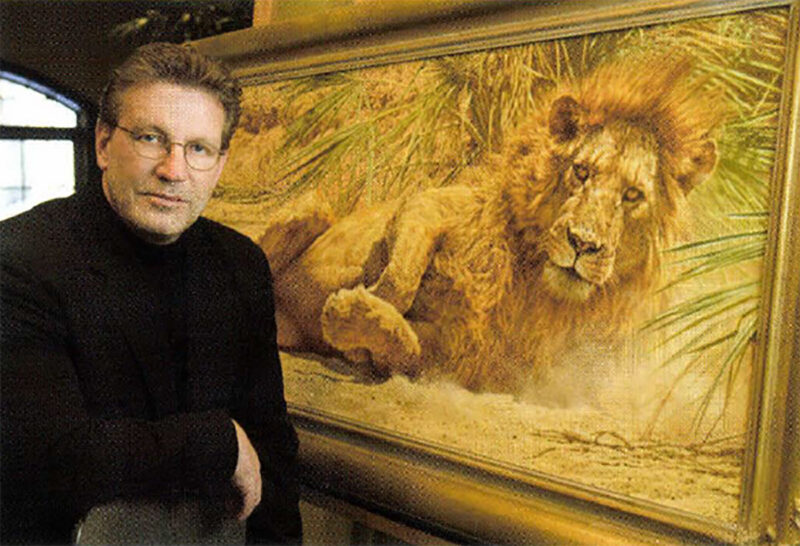

Brain Jarvi with The Rising

Nowhere is the tension more palpable than in the nations of southern Africa, where a dedicated group of conservationists and artists have stood in the breaches of tumultuous change to protect wild animals and their habitat.

Brian Jarvi’s hypnotic paintings of the hunt, with their swashing flair and heart-palpitating action, remind us precisely what is at stake for the places where our wildest dreams dwell.

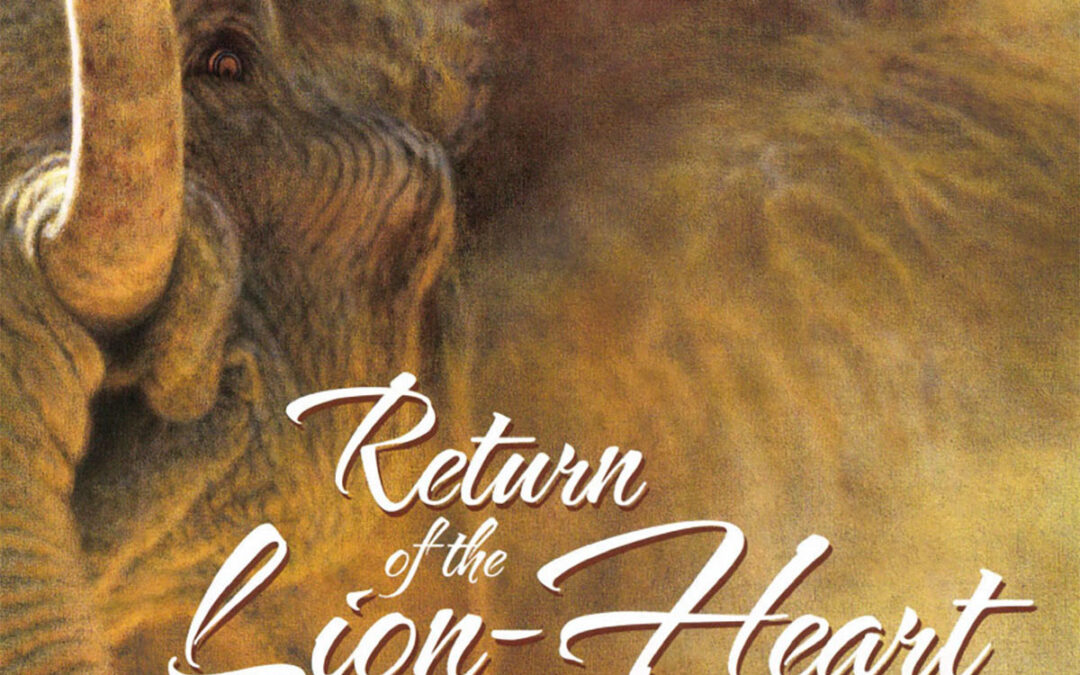

It’s profound and more than a bit uncanny that as tectonic economic forces continue to rumble globally, Safari Club International’s 2009 Conservation Artist of the Year’ debuted a portrayal of elephant bulls locked in a battle for survival.

And the viewer knows not what the outcome will be.

Brian Jarvi is one of the most dramatic painters of wild Africa I know of, and I don’t make the observation lightly,” said Ross Parker, the Zimbabwean-born founder of Call of Africa Galleries in Fort Lauderdale and Naples, FIorida.

“You can be sure he is not a flat-footed artist,” Parker added. “He attempts to go beyond the cutting edge in terms of how he gathers reference material. What he does is different from anyone else. No matter what your preference is in wildlife art, his paintings are entertaining.”

For his elephant piece, The Last Gladiators, Jarvi drew from a deep well of personal adventures in game reserves that span a vast arc stretching from the foot of Kilimanjaro on the Serengeti to the Okavango swamp, Kalahari Desert and the bushveld of Zimbabwe and South Mica. In a way, the grand painting also marks a return for Jarvi from a period of relative personal hibernation.

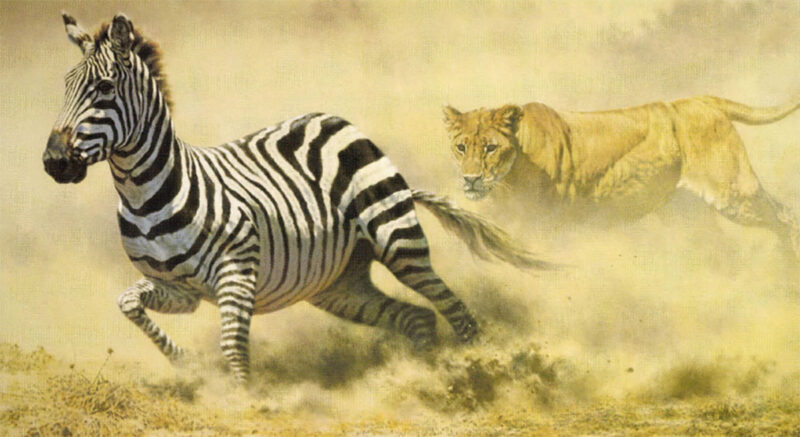

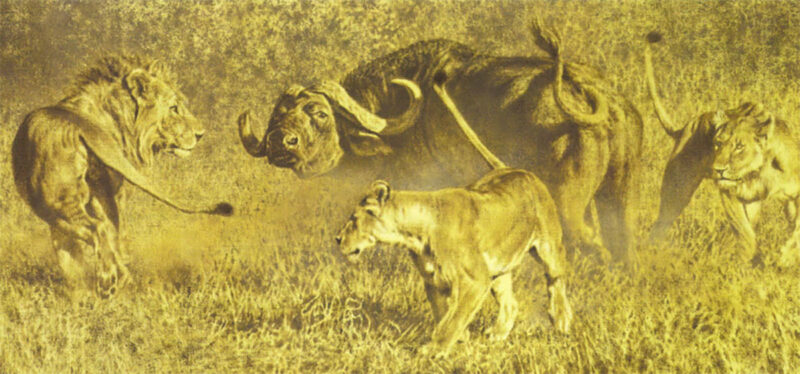

Razor’s Edge

Parker referred to Jarvi as a “lion-heart,” an artist who goes to considerable lengths to achieve authenticity, but who creates paintings that stand apart from most of the wildlife art produced today. He is as well known in England and Europe as he is on U.S. soil.

“Brian is a successor to a long line of great painters from North America who adopted Africa and carved out their own legacy at events like Safari Club and Game Coin, guys like Bob Kuhn, Robert Bateman and Guy Coheleach,” Parker said. “Good painters evolve.”

Born in 1956, Jarvi was raised in the north woods near Floodwood, Minnesota, soaking in a visual range that shaped his romantic perception of nature. Moose, deer, black bear and bobcat inhabited the post-glacial topography of lakes, evergreens and glowing white birch forests. Every once in a while, as loon song echoed over the cold water tarns, there were howls of timber wolves heard at dusk.

“It was a great place to grow up,” he recalled. “My family lived on the edge of town and the St. Louis River was 15 feet away from back of the house. The river flowed through a network of islands and it was, you could say, almost Huck Finn-ish.”

Finnish in another way, too. The grandson of immigrants from Finland, Jarvi spent many autumn days hunting waterfowl, trolling for walleyes, flushing ruffed grouse and woodcock from blight, leafy understories and being haunted by ghostly and elusive whitetail bucks. But he spent countless hours merely observing, studying the silhouettes of animals and how they moved through landscapes, taking stock of the atmosphere in the sky, noticing shifts in color as the sun highlighted focal points and cast others into shadow. His ability to absorb the essence of a place is what makes his portrayals of Africa so potent, art collectors say.

“Definitely, my love for the outdoors came before I started to be an artist,” Jarvi said from his studio in Grand Rapids, where he immerses himself in a creative space full of reference material, including a lion’s skull, tribal artifacts, animal skins, sketches and photos. “My identity in the land was something that became engrained early, and I still feel very lucky having the opportunity to many those passions.”

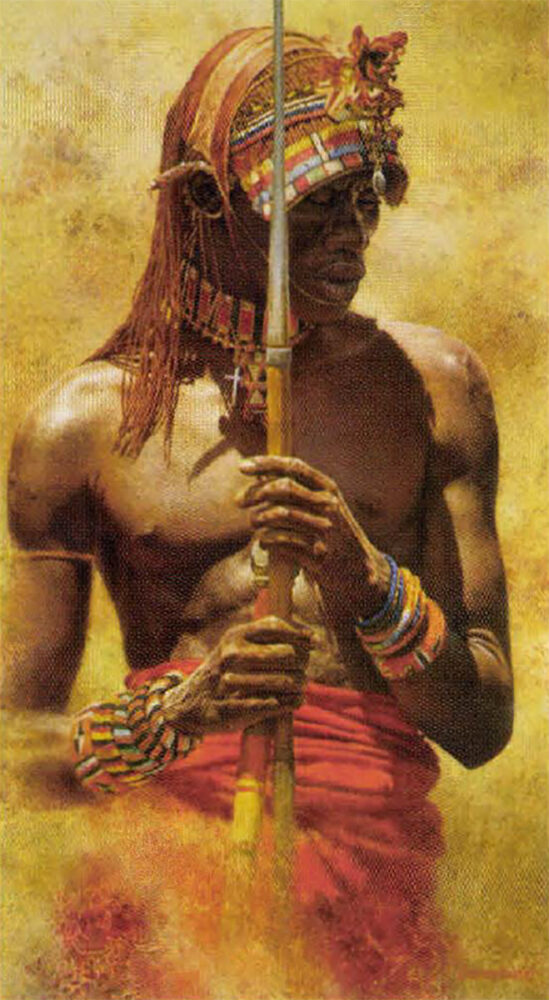

Samburu Warrior

The journey that ultimately led him to Africa could not have been predicted. At his small high school in Floodwood, the curriculum offered no art classes to a boy inclined to draw, which meant his talent wasn’t formally recognized nor nurtured.

Thus, the possibility of entering a college cut program never presented itself. Instead, Jarvi went to work for Burlington Northern Railroad (an ironic career diversion that foreshadowed one of his most resonant paintings). He spent 13 years maintaining track line, though the irrepressible urge to document the wilderness around him could not be contained.

It was during his time with the railroad that Jarvi perfected a remarkable skill: Whenever he couldn’t draw animal gestures on paper, he committed the images to memory, compiling a mental library of observations.

Eventually he bought a paint kit and, by studying the works of masters at museums and in books, he developed his own style.

Down the highway is the tiny town of Aitkin, where Frances Lee Jaques, who painted dioramas at the Museum of Natural History in New York City, retired and set up a studio, rendering many of his waterfowl masterpieces in which the skyscapes themselves set the stage for action. Jaques, who died in 1969, demonstrated how sporting art could be pushed far beyond mere illustration.

In the early 1980s, Jarvi entered a few pieces in duck stamp competitions. The problem was that Minnesota in those days was a mecca for great sporting musts, the likes of which included David Maass, Les Kouba, Terry Redlin, Daniel Smith and the phenomenal Hautman brothers, Jim, Robert and Joe.

In 1985, Jarvi broke through. His portrayal of blue bills on lavender water was selected to appear on the Minnesota Duck Stamp and the following year one of his paintings adorned the pheasant stamp. Despite these triumphs, he felt bored artistically.

Jarvi rapidly expanded his portfolio by tightly rendering North American mammals and birds, winning him notice and offers to publish his work. Then, in 1989, he made his first trip to Africa as part of a delegation of artists. Funded by a publishing company, the photo safari included Kenya and Tanzania where the artists explored the game reserves of Ngorongoro, Amboseli and Masai Mara. One of Jarvi’s traveling companions was big game painter Daniel Smith, a fellow Minnesotan who, like Jarvi, felt transformed by the experience.

Desparate Measures

“When I first landed in Nairobi, it was like arriving on a different planet,” Jarvi said. Nearly a dozen pilgrimages and a hundred bush camp sunrises and sunsets later, he admits it took a while to fully grasp the aesthetic nuances of the African savanna and veldt, but it infused his sensual inclinations as an artist with a purpose.

Ross Parker, who joins artists in Africa every year says it’s uncommon for a North American painter to create visual narratives that read true to the experiences of professional hunters and locals who live it every day. Most unknowingly assert their North American aesthetic onto the canvas, which is a mistake. This is why Jarvi now paints African subjects exclusively, to shed any possible distractions.

“I have always believed that the best artists are either born in the setting they paint or they adopt them as their home, and by taking the time to know them intimately, they become reawakened and reborn,” Parker explained.

“Brian Jarvi obviously understands mammal physiology and anatomy, but his ability to translate the drama of Africa is exceptionally rare. I grew up in the bush and have witnessed plenty of extraordinary things involving wildlife. Brian paints pictures that stop me in my tracks.”

Jarvi’s elephant painting premiered at SCI’s exhibition along with several other pieces, among them a provocative nighttime scene of the man-eating lions of Tsavo. He explained that his principle ambition is making scenes that provide an escape for the viewer, not unlike the classic predicament scenes that adorned magazine covers in the 20th century.

The Last Gladiators sprang from a memorable research trip to Sambwu National Reserve in Kenya’s Rift Valley Province. Jarvi was quietly observing game converging near a waterhole when a territorial clash erupted between two mature tuskers bearing down on each another not far from where he stood.

“A battle of elephants is the greatest kind of confrontation in the natural world, at least on land,” Jarvi said. “The sound and the power of two beasts that size makes the ground shake. It engulfs you in a way for which the outcome isn’t known. It’s a remarkable thing to witness.”

Savage Land

“Brian has developed a unique style that is immediately recognizable,” noted friend and fellow painter Dan Smith.”His immense talent has provided him with an uncanny ability to capture the true essence of Africa and its wildlife. His work continues to inspire me.”

Jarvi’s work has been featured in a number of museum exhibitions. Over the year’s Hiram Blauvelt Art Museum in Oradell, New Jersey has staged dozens of wildlife art shows, including several focusing on African animals. An event celebrating the tenth anniversary of Artists For Conservation featured more than a hundred paintings and sculptures by artists from 27 different countries. Marijane Singer, the Blauvelt’s director, remembered the public response to Jarvi’s painting, The Rising, which depicts a lion suddenly startled from its slumber by some unknown sight or sound.

“Someone came in and spent a long time enjoying all the works, then paused before Brian’s painting and said, ‘I can tell that HE doesn’t paint just from photographs. He goes to Africa,’” Singer recalled.

“Brian Jarvi’s work excites me because he’s young and he commands the same qualities as you see in works by the old masters,” Singer added. “His pieces are very powerful.”

Ross Parker vividly remembers a major Jarvi painting that he saw at an SCI show in Reno. Entitled Return of the Wildebeest, it portrays a pride of lions preparing to engage a vast herd of plains animals as it enters a valley on its ancient seasonal migration. The painting has a monumental quality to it.

“I try to save my greatest concepts for major pieces that go beyond simple portraiture,” Jarvi said. Grandness is sometimes a profound understatement, for he has painted across stretched surfaces as large as six by eight feet. Like many of his predicament scenes, this one started with a storyline that had been evolving in his mind, an encounter between lions and wildebeest he had observed in half-a-dozen different counties.

Return of the Wildebeest is not a replication of a photograph. It is a composite of earlier experiences, melding an attractive landscape that serves as a backdrop, with the classic tenets of sporting art drama that leave us guessing how the scene will culminate. Each viewer can ponder a different outcome.

“For me, the muscularity of lions makes them an enjoyable animal to paint. A lot of my work is done in brilliant overhead sunlight … high-contrast situations, exaggerating the definition of an animal’s body, which I find intriguing,” Jarvi said. “Obviously, what I enjoy most about painting them is the opportunity to create drama and tension.”

The Last Gladiator

He spent two months developing the painting beforehe applied a Single brushstroke, preparing two studies and shifting elements until he got the design exactly right. “It’s not so much about getting the anatomy of the cats right. It’s getting the scale right between the different lions in the scene and the panorama they’re in,” he says. “It’s all about the angles you use that pull the viewer into a scene.”

Ever since he took his first hip to eastern Africa, Brian Jarvi has aggressively courted opportunities to get away from the confines of the Land Rover and stroll into the abyss on foot. Back in the studio he is able to re-summon the visceral feelings he experienced as lions roared and moved through the tall grass around him.

Brian Jarvi has always been generous in his support of grassroots conservation and in 1999 he served as SCI’s conservation artist of the year. Ensuring survival of the subjects he loves to paint has assumed ever-greater poignancy when he took on helping his wife, Raelene, in her battle with cancer. Jarvi had been making annual trips to Africa, but when Raelene got sick, he put them on hold to stay close to his soul mate as she underwent treatment at the Mayo Clinic. Fortunately, Raelene got well again, and collectors note how her recovery seems evident in the vitality of Jarvi’s paintings coming off his easel.

“Brian’s palette is so confident and his choice of color has shifted,” Parker said. “He is a lion-heart entering his prime.”

Reign of Terror – The Man-eaters of Tsavo depicts the two infamous lions as they skulk through the camp of workers on the Kenya-Uganda Railway.

“If a piece like this is executed well and you are a sportsman, it should send shivers down your spine,” Jarvi says.

“If it doesn’t, then the reasons are obvious.”

The artist need not worry. The grand 40×60 nocturne already has created a great deal of excitement among his loyal fans. Not merely does the painting cut directly to the primordial chase of predator and prey, it signals an artist merely in a steady state of evolution in skill, hunger and heart.

Good painters, after all, evolve.

Following best seller and award-winning book “Beast” we are pleased to announce the release of “King of Beasts” by John Banovich. Featuring 208 large format pages, “King of Beasts” illustrates the dramatic artwork of John Banovich, all focused on depicting the extraordinary African Lion. An internationally recognized artist who has studied lions for decades, Banovich has selected a body of work that pays homage and explores questions about mankind’s deep fear, love, and admiration for these creatures. Buy Now

Following best seller and award-winning book “Beast” we are pleased to announce the release of “King of Beasts” by John Banovich. Featuring 208 large format pages, “King of Beasts” illustrates the dramatic artwork of John Banovich, all focused on depicting the extraordinary African Lion. An internationally recognized artist who has studied lions for decades, Banovich has selected a body of work that pays homage and explores questions about mankind’s deep fear, love, and admiration for these creatures. Buy Now