Hunting sculpts intrigue into incomparable adventure, places us center stage, and folds us into the metamorphosis.

These Georgia sportsmen number among the 50 million Americans who hunt or have hunted at some time of their lives.

At the New York office of Blount, Reynolds, and Poirer, the torch of jurisprudence will pass to eager young associates for a spell. The senior partners are off to the pin-oak bottoms of the lower Mississippi. Mid-continent mallards are the best since the ‘70s. In the pre-dawn chill of the small hours near Red House, Nevada, a bleary-eyed gear-jammer nurses a steaming cup of java across the backyard and into the towering cab of a Kenworth. The rejuvenating surge he feels as the great diesel roars from slumber and trembles on its springs is the promise of a short run. He’ll be back by early afternoon for a go at the mulies. And silhouetted against a faint circle of fire glow on a balding knob in the Ozarks, a grizzled octogenarian in faded Osh Kosh cups a hand to his last good ear, straining to preserve communion with the foxhound belling somewhere yonder in a moonless hollow.

Gone huntin’. A persuasion of the spirit as indelibly infused into the American character as the colors of Old Glory Captivated by its irresistible trilogy, we exalt in adventured exhilaration, covet the eclectic grandeur and serenity of its theater, and embrace searing self-perceptions of identity and individuality, ethics and morality, courage and perseverance, integrity and honor.

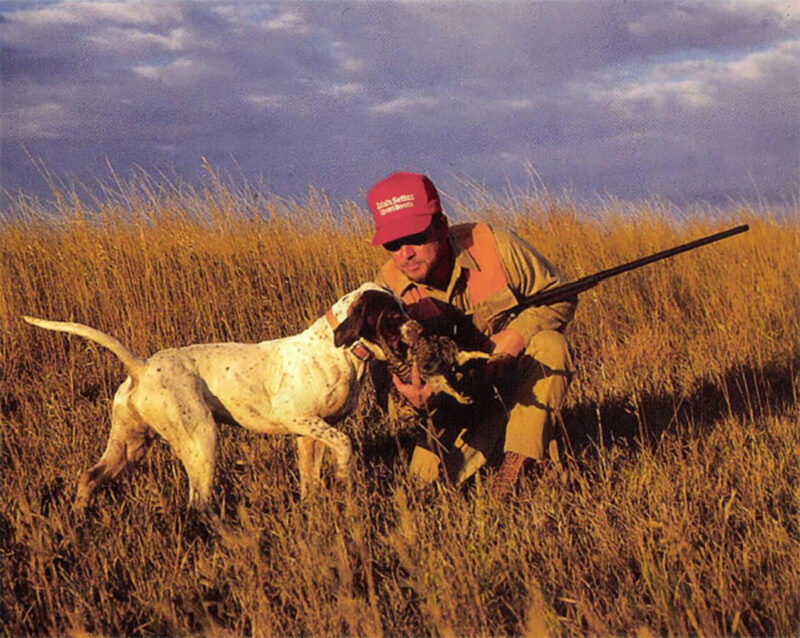

There is a fundamental wholesomeness about a father taking a son or daughter hunting for the first time that taps the robust decency we like to affiliate with America and being an American, an adventurous cohesion that wanders back to the foundry of family origin. In forests and by streams there is a dependable gentleness which asserts the merits of our existence, that seeps into our emotional marrow to instill revered values. In the eyes of a sporting dog is the offer of friendship, faithfulness and harmony. In the heft of a gun, the weight of responsibility. The boy or girl who comes up afield is apt to be a pretty respectable human.

At the threshold of the twenty-first century, it is intriguing but not surprising that a sports popularity index released by the National Sporting Goods Association at the World Sports Expo ’94 shows hunting among the top five participative sports in 18 states of the Union, while baseball, the “national past-time,” ranks similarly in only three. According to the most recent National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (F&WS), more than one-quarter of all living Americans six years or older, almost 50 million people, hunt or have hunted at some stage of their lives.

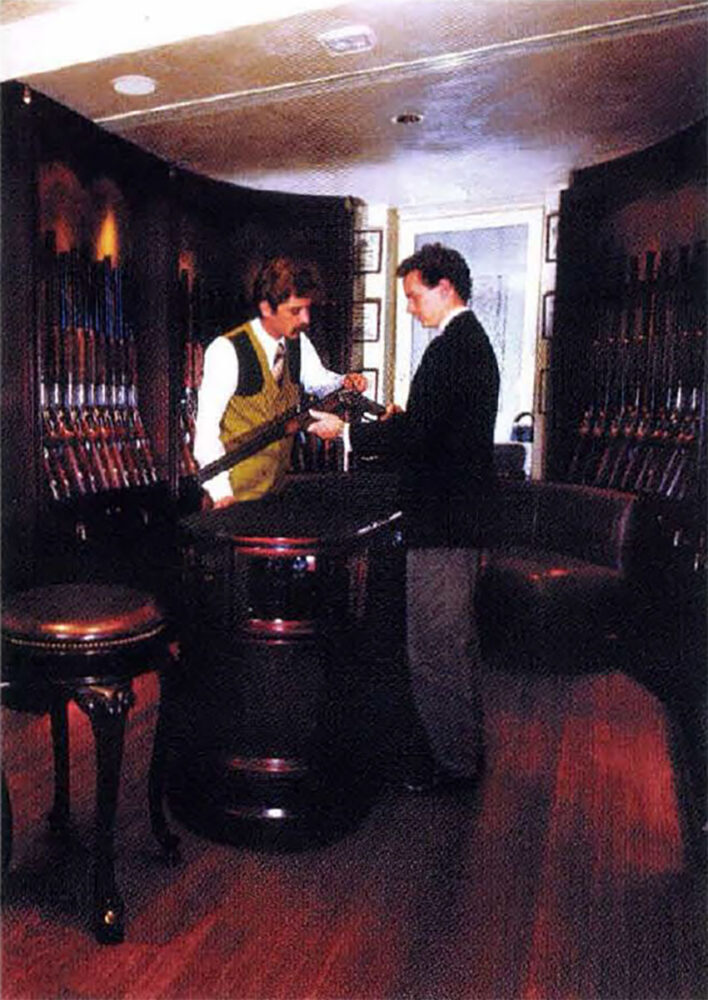

This man’s purchase of a new shotgun will bring more tax dollars to wildlife via a special tax requested by America’s hunters.

It affects us and those about us profoundly: economically, socio-politically, culturally, psychologically, while the nomadic footprints of our quest stipple every eco-system on the planet. Within these reaches reside tremendous accountabilities, and issues of the heart and mind which demand the limits of human sensibility.

The commercial significance alone is immense. In a modern society where pursuit for subsistence is long since vestigial, we still hunt so fervently, over 235.8 million days each year, that the associated mercantile trade has become a global industry with annual revenues surpassing those of Coca-Cola, McDonalds, Johnson & Johnson and scores of other revered Fortune 500 companies.

The headwaters of this economic well-spring gather inconspicuously, at the very quick of American enterprise. In the unpretentious township of Rich Square, North Carolina, Claudine Outlaw, operator and sole proprietor of Claudine’s Restaurant, has catered to an autumn equinox of whitetail hunters for 16 years. At least 50 percent of her livelihood is realized September through December. “During the peak of the season,” she says, “we may have 50 hunters here for breakfast, even more for supper. They tell me deer stories; I tell them to eat hearty, the car payment’s due. We laugh at it all and they keep coming back.”

Bob Berning operates Berning Motor Inn in Creston, Iowa. The pheasants are up . . . the CRP influence. So are the hunters, adding about 25 percent over normal receipts October to January. “Hunters are good customers,” he observes, “they come in and spend money, have a good effect on the community. I have hunters who invite farming families in for dinner in appreciation for the hunting privilege. A little kindness goes a long way.”

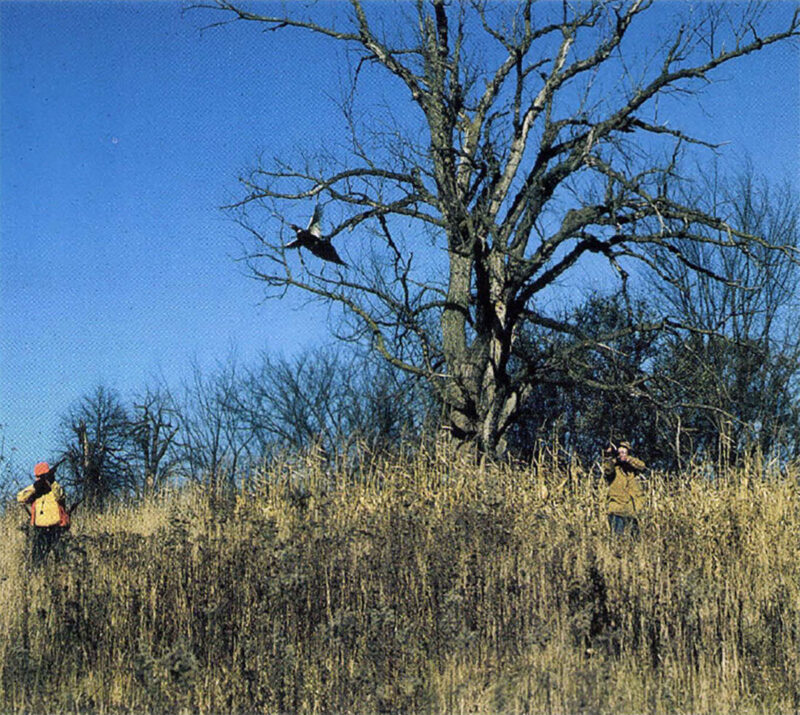

Grouse and pheasants are benefiting from more habitat left by Midwest farmers who realize a source of revenue from hunting.

In turn, farmers struggling with the fickle economics of agricultural profitability are discovering a steady source of income from hunters willing to pay for access to promising game lands. Like the rancher in Texas with the bovinely inhospitable 68,000 acres, where the grass has given over to mesquite, cactus and buckbrush (which just happens to be beautifully-classic southern whitetail habitat), who dropped the cattle business and divided his holdings into hunting pastures. For $22,000, five guys can lease one and take an outstanding buck each season. Everybody’s happy. And guess what … the grass is coming back. In South Dakota, many farmers are finding that those odd corners so resistant to the plow make great low-risk pheasant incubators, and that the hunting guys who come in every year from Illinois and Minnesota are glad to fork out their hard-earned dollars to improve their chances for a limit of cockbirds. Other landowners are deriving a comfortable profit by diverting random acres into sporting clays layouts and shooting preserves.

On it swells. In the White Mountains of northeastern Arizona, where ranching and logging have been the traditional ways and means, the supplemental recreational dollars invested by elk, mule deer and turkey hunters in 1994 amounted to more than $2.5 million, enough to run the Police Department in the adjoining town of Pinetop Lakeside for three years. In Greenville, Maine, pop. 1,800, local business folks eagerly anticipate the flush of resident and non-resident hunters, press reps and spectators prompted by the October moose season. “It gives us the economic boost we need to weather the winter,” Cynthia Hanscom, town bookkeeper, avers gratefully. Last year, hunters spent over $123 million in New Jersey, $548 million in Georgia, $1 billion in Texas.

According to the most recent data released by the F&WS and the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), it crests nationally with more than 14 million hunters contributing in excess of $14 billion annually to the U.S. economy, and supporting over 380,000 jobs. Moreover, the Wildlife Management Institute estimates that expenditures by hunters stimulate a “spin-off” of perhaps $14 million more in coincident business. The wildlife art industry is a good example: there are some 5,000 galleries across the country that cater to the national fondness for wild animals, much of it ignited by hunters. Putting all this in perspective, consider, despite the hype and allure, Brad Pitt withstanding, that the motion picture industry’s yearly gross from theater admissions is about five billion.

We spend as passionately as we pursue. And then spend some more. Money, ideals, lifetimes. There is a certain humility to the hunt. Pulled to our knees by staggering moments of truth, we recognize that before us, in spite of all our contrived importance and conceit, there is the air, the land, and the water, and despite the fact that we have inserted ourselves more intricately into the machinery of its heartbeat than any other species, we are still less than an afterthought to the immense inner-workings of our ecosystem.… and only that … still mortally dependent as all other creatures upon its deeper breath and rhythm, and bound inextricably by our superior intelligence to the awesome responsibility for its preservation as we wish to know it.

Hunters have spearheaded the century-long fight to save our wetlands and waterfowl.

With this insight hunters become conservationists, some of America’s greatest. Among the 23 portraits on permanent display in the National Wildlife Federation’s Conservation Hall of Fame, many of the images and names are quite familiar to hunters, obelisks of pride. Theodore Roosevelt, George Bird Grinnell, Ernest Thompson Seton, Aldo Leopold.

Hunters have, of choice and respect, stood at the pilot wheel of the conservation commitment from its port of origin. It began of extraordinary courage and conviction over 150 years ago, when nearly all of America was wantonly affixed to the proposition that wildlife and forestry resources were boundless. As the bison was emerging a political pawn for reducing the plains Indians to subjection … As the ladies of polite society unwittingly flocked to don a death wish for shorebirds … A stalwart group of New Yorkers formed a Sportsman’s Club to enforce game laws and protect game from market hunting and poaching. It was the leading edge of a swift and righteous sword. In 1872, upon the behest of sportsmen, Yellowstone became the first wilderness area set aside for the protection of wildlife. In 1887, the Boone & Crockett Club was chartered to fight for the preservation of big game species. In 1900, the Lacey Act spelled the end of market hunting. Momentum. The first National Wildlife Refuge. The Migratory Bird Act.

Perpetuation became adjunct to conservation, and perpetuation paramount to tradition. Assurances were crafted. A remarkable and unprecedented coalition of conservationists, sportsmen and firearm/ammunition manufacturers joined with state wildlife agencies to launch and guide a visionary trust through Congress. Its concept would place a perpetual excise tax on ammunition and firearms used for sport hunting, with the revenues accruing to wildlife restoration. In 1937, the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (Pittman-Robertson Act) became the law of the land, the monolith of salvation for some of our most cherished and endangered species, each a contemporary success story: the Rocky Mountain elk, the Canada goose, wild turkey and white-tailed deer. In this country, the voice of popularity frequently and sometimes rightfully harangues taxation as a chilblain of frigid government. I proudly assert that in fifty years of at-large association with hunters at their most casual, I have never heard a solitary, begrudging utterance about Pittman-Robertson.

The Canada goose population has soared to record levels in large part because of the nation’s extensive system of wildlife refuges, much of it bought and paid for by hunters’ dollars.

P-R receipts are up significantly. “Over 25 percent,” reports Hugh Vickery, F&WS spokesman, “and they will continue to increase impressively in 1996.” This is in good part due to codicil self-assessments in ’70 and ’72 which have added additional revenues from handgun and archery sales. In FY ’95-’96, P-R will apportion $211 million to the states: $171 million to wildlife management, $40 million to hunter education. This is the latest installment in an enabling legacy which has returned over $2.6 billion since inception.” Hunters and fishermen continue to be a cornerstone to conservation in America,” affirms Secretary Bruce Babbitt, U.S. Department of the Interior.” Their contributions through excise taxes paid under federal aid programs are vital to maintaining and restoring our nation’s fish and wildlife resources.”

Intrinsically more obscure, but equally significant, are the dollars spent by hunters for licenses, permits, tags and privilege stamps. Currently, there are 15,343,000 legitimized hunters in the U.S., who have purchased 31.6 million “licenses.” This represents an additional $525.7 million conservation dollars over P-R funds, since by foresight, these monies too have been earmarked for return “to the resource.”

Thereby, each general fund tax dollar appropriated by the states to wildlife agencies is matched by over nine from sportsmen.

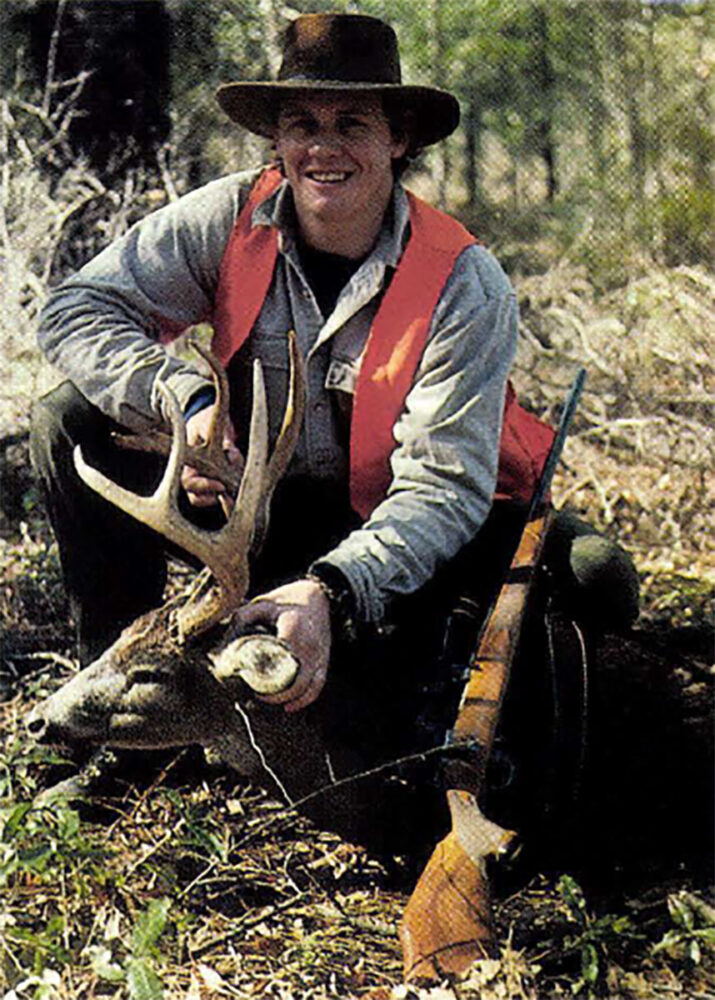

Who can deny the spectacular comeback of the white-tailed deer, a resurgence championed by hunters in time and dollars.

Still, our zeal for perpetuation is not satiated. Through over 10,000 private groups and organizations, such as Ducks Unlimited, Pheasants Forever, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the Wild Turkey Federation, we contribute $300 million annually for conservation activities. Finally, hunters as a group engage more universally in “non-consumptive” wildlife-associated recreation and give more generously to “backyard” wildlife programs than any other segment of society, despite the fact that of the more than 1,150 species of birds and mammals in North America, only about 145 are legally hunted.

Does the equation perk? What of the repercussions of hunting on the resource itself? Conservation and management commitment withstanding, can 145 wildlife species sustain 235.8 million hunter-days year-in and out? Succinctly, yes. Long-term studies and data from the Wildlife Management Institute and the F&WS indicate that scientifically managed, regulated hunting in the U.S. has not caused any wildlife species to become extinct, endangered or threatened, or adversely affected the ability of wildlife to prosper. To the contrary, many hunted species, particularly large game, are increasing.

Success stories are reaching epic proportions. In Wisconsin, the whitetail season just past was a 21-carat phenomenon! From a pre-season herd now estimated in excess of 1.5 million animals, hunters took more than 460,000 deer, an all-time record which eclipsed the ’94 harvest by more than 85,000, and also includes an unprecedented buck tally. Play that back for a moment against estimates that place the turn-of-the-century whitetail population for the entire nation around 300,000. Everybody’s overwhelmed, including the biologists who frankly admit “there were more deer out there than we thought.” So many, in fact, that despite the astonishing harvest, it is likely that winter carry-over combined with spring fawning will considerably exceed the desired management level going into next fall.

Meanwhile, a growing number of non-hunted species are being threatened or endangered by indiscriminate traditional industry, “mall sprawl,” or associated metro-business expansion. Many of these species now cling to fragile habitats nurtured by hunter dollars.

To millions of Amen’cans, hunting invokes an endless longing and an insatiable wanderlust, whether it be in a snowy grouse woods of Minnesota or in the pheasant fields of Kansas.

The economic subsidies from hunting are becoming ever more important to the perpetuation of America’s natural heritage as farming practices which sustained wildlife continue to digress within the stress of a global market, as land management plans trespass and fragment crucial habitat, and as public access to private lands diminishes.

Yet, for all this, hunters find themselves unappreciated and maligned by an aggressive segment of contemporary society. The values and validity of hunting, once almost universally esteemed, are now challenged by some as unconscionable tenets of moral degradation, attributed to everything from Freudian sexual aberrations to involuntary proclivities of dominion. Under the correctly knit-and-purled banner of animal rights, unfurled with the pentameter of civil liberties, protagonists are striving mightily to push hunting into the lap of middle America as a controversial political issue.

The latest edition of the Encyclopedia of Associations includes two pages of fine-print listings for animal rights and welfare organizations. A sobering number are actively pursuing goals which include the outright abolishment or curtailment of hunting. A host of others are poised on the fringes with sweeping mission statements inferring related interests, susceptible to involvement by mild incitement and occasion. Most are content to assertively disseminate and debate their point of view. Some are ultra-extreme. Coterie titles like the Animal Liberation Front and Hunt Saboteurs say it all, and have been associated with many harassment incidents and allegations of physical violence regarding legal hunters. The campaign now encroaches cyberspace. Surf the Internet closely, and you’ll find a slickly configured “encyclopedia of direct action” which advises anti-hunter activists of protest and sabotage strategies.

The fanaticism marks the extreme right of the galvanized intensity of emotion generated by the fundamental apogee of hunting: the taking of a life, an accountability for death. An issue of the heart. All conscientious hunters have embraced it solemnly many times.

In the stealth, vigor and heart of wild creatures is found a measure of “wildness” that we long for in our own lives.

We live in a democracy. Freedom of speech, challenge and hunting are accordant privileges. By way of logic and demonstration, we have the opportunity, but not the right, to perpetuate a way of life deemed compatible with the greater good of the people … to maintain the liberty to choose a particular path, especially in matters of the heart. Fortunately, extremism seldom prevails on either side of an argument. The battle is enjoined for the sensibilities of the middle.

The cost of freedom forestalls arrogance. The price of choice is respect.

As an extension of its 18-year Outdoor Ethics Program, the lzaak Walton League of America released a revitalized Code of Conduct for Hunters, the crux of which is a nine-point pledge of responsible behavior. The Code was developed in concert with a broad array of America’s most highly regarded hunter/conservation organizations. “It has long been the view of the League that the battle for the future of hunting is a struggle for the hearts and minds of non-hunters,” declares Paul Hansen, IWLA director, “and that the best thing hunters can do to maintain the hunting tradition is exhibit a proper code of ethics. Most people will support safe and ethical hunting.”

Meanwhile, the NSSF continues to spearhead a rejuvenated observance of National Hunting & Fishing Day. The 1996 celebration on September 28 was one out of a liturgy of recognition established by a joint resolution of Congress more than a quarter-century ago, which has reached over 20 million Americans with goodwill events and educational programs conducted by sportspeople.

These efforts represent the vanguard of a sincere counter-concern, reaffirmation of social responsibility and concurrent appeal for deeper understanding by the hunting fraternity across the whole of America.

Beyond heritage, beyond tradition, beyond the politics of society, there must be a basic, driving purpose to individual existence, a touchstone of sanity in a frequently insane world, a harbor for restoration that reinvigorates the desire for compatibility and survival.

For each of us, purpose is as fundamental as the Constitution, and synonymous with our perception and expression of freedom itself. I don’t always identify with another fellow’s design, nor can he readily explain it to me, but I understand and respect the chemistry.

In the course of a lifetime, many people, places and things court our passion. Most gain little more than passing notice, some slip into affairs of transient infatuation, but only a certain few, a very few, become so profoundly and irreplaceably grafted to our soul that no day of our life is ever again complete in their absence, and each period of separation becomes a marathon of longing.

Hunting is grafted irreplaceably to the soul of millions of Americans, invoking an endless longing, a boundless anticipation of tomorrow, an insatiable wanderlust that remains forever in search of reunion, six miles down a county road to a woodcock covert or across a continent for Tanzanian buffalo. In the stealth, vigor, heart and courage of wild creatures I found a measure that we long for in our own lives, a “wildness” in a world grown too prescriptive, too monochrome, too tame.

There is a scene I love from the screenplay for lsak Dinesen’s entreating novel Out of Africa, which epitomizes the untamed promise of the hunt. It arises from the mellow intimacy of firelight at the end of a day at safari. Denys has related to Karen the need to be about early on the morrow, and inquisitively, she asks, “And what happens tomorrow?” Pausing several moments, a wonderful expression of wonder washes across his face, and he replies, “I have no idea.”

Hunting sculpts intrigue into incomparable adventure, places us center stage, and folds us into the metamorphosis. It happens almost equally, whether in a familiar woodland or the breathtaking splendor of a wilderness, in solitude or chosen company, though never twice in exactly the same way. In ever-changing moods, with each turn of the sun and the moon, the wind and rain, it transports us from prosaic convention to the remote and otherwise unattainable destinations of the spirit which analogue the seasons of our lives. Riveted with suspense, we trust in and await with exhilarated anticipation the unfolding unknown on the next minute, the next hour, on the morrow.

Hunting is grafted irreplaceably to the soul of millions of Americans, invoking an endless longing, a boundless anticipation of tomorrow, an insatiable wanderlust that remains forever in search of reunion, six miles down a county road to a woodcock covert or across a continent for Tanzanian buffalo.

With the wait, we’re gifted even more: exquisite places and crystalline moments that become an inseparable part of us for the length of our days. We learn to retreat there in the times of our greatest need, when despondency annihilates confidence and draws us hard against dark and frightening places, when the well-intended ministrations of human civility fall short of healing, to seek the soothing voice of silence. For the hunt is not always for another creature. Sometimes it is for ourselves that we must search most earnestly. In the stealth of winter snowfall, the spoor of vagabond winds trading through prairie grass, the scent of the earth as it rises on the chill of evening, we find a way ahead.

Nothing so special comes without recompense. With the heightened sensitivity to life and its fragility is exacted an acute comprehension of our own mortality, and a constant inner search for personal standards of self-respect and integrity. The love affair of any lifetime is rarely devoid of pain and doubt.

With each separation, we are reacquainted with the depths of our commitment. We comfort ourselves with the talisman of memory, so that it can never be far from heart or feel or touch … a wisp of feather pressed between the pages of a favorite book; the small, silvered seed-cone from a high-country spruce, precious, silky strands that cling after all the years to a worn and darkened dog collar; the centerfire rifle brass so inappropriately appropriate in the executive desk of a high-rise office suite. These talismans wish us forward, whisper to each of us in quiet, validating moments … yes, in this life I have been there, this is what I live for, and I must return.

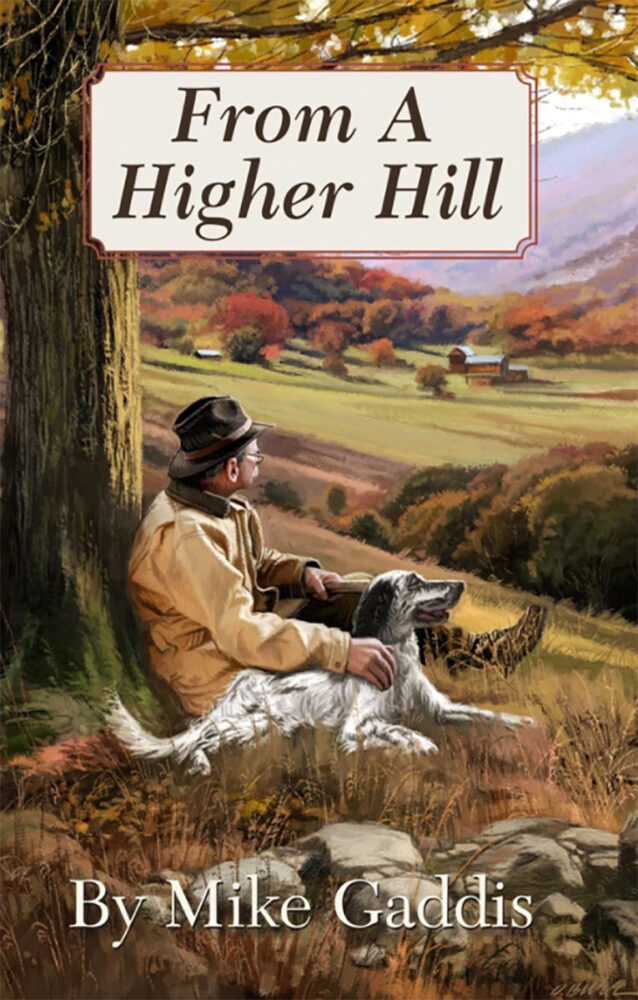

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now