No dedicated hunter or fisherman can afford to turn a blind eye. Here are some suggestions on how to be proactive and make a difference.

Earlier today I canceled insurance coverage on my home and truck with the carrier I had used for years and switched to a different one. My reason for doing that, never mind a fair amount of paperwork and hassle, had little to do with finding a better deal (although I did save a bit). Instead, it was one individual’s protest of the political stance taken by the company in various television ads. The insurer was spending money (almost $20 million) on ads supportive of social and political views inimical to almost everything I believe. I have no intention of spending my dollars for such folderol.

This particular matter had scarcely touched my perspectives as a sportsman, but it did, along with the highly destructive and ongoing brouhaha connected with the National Rifle Association’s leadership and operations, serve a useful purpose. They were twin catalysts reminding me that as an outdoorsman I have real and deeply meaningful responsibilities which I should meet just as I do ones relating to other aspects of my life.

For most of us, those precious hours we steal from the mad rush of the real world to spend in a deer stand, on a trout stream or roaming turkey woods are intended to provide an escape from worries and problems. They enable us to experience closeness to the good earth, throw aside work burdens and at least temporarily forget the concerns which all too often loom large in our daily lives. Yet any hunter or fisherman who really cares about sport and its future should, along with soothing his soul through time spent afield, search that soul for solutions to problems affecting us all. That’s what I’m attempting to do in the thoughts which follow, and chances are I’ll step on some toes along the way. So be it. I never garnered any laurels for diplomatic skills and as I grow older I become more convinced of the importance of saying what you think, although certainly it can and should be done in a civil manner. You don’t have to agree with what follows but I would fervently hope that you at least respect me enough to think about what I have to offer before getting defensive or dismissing me as yet another curmudgeon completely out of touch with the world in which we live.

Learning to Speak Up

An inescapable reality of life today is that enemies of hunting and to a lesser degree fishing confront us on numerous fronts. They come in varied forms, some subtle, some cleverly disguised and some blatantly obvious. No one would argue that high-profile groups such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals or the Humane Society of the United States, constantly clamoring for dollars and “dissing” sportsmen, are anti-hunting. But what about the various gun-control bodies, organizations such as the Sierra Club which ostensibly support hunting but leave real doubts on that front when you review their verbiage and actions, or even wolf in sheep’s clothing groups which are supposedly pro-hunting but raise significant questions when closely scrutinized?

Then there are two stark and discomfiting realities which have emerged, painfully and gradually, but with insidious persistence, over the course of my lifetime. The first is an ongoing decline in available public lands for hunting and a similar reduction in hunt club opportunities as the timber business went to hell in a hay cart and investors gobbled up huge tracts of land which suddenly were no longer available for lease by hunters. If we stay on this path our grandchildren will live in a situation similar to what exists in most of Europe—only the quite affluent or well connected will be able to hunt. Fishing access, especially on free-flowing trout streams, has also become a growing problem.

You can add to that another troubling, long-term development which no thinking sportsman can deny. Far too many of those who should be kindred souls are enemies in our midst. I’m referring to slob hunters, poachers, trash tossers, and n’er-do-wells who lack respect for not only the land and creatures for which they are hunting or fishing but for the good earth in general. I got a first-hand example of that some two decades ago as a member of a hunt club which leased land from a timber company. I was already frustrated with yet another example of timbering devastation, complete with aerial spraying and streamside management zones so tiny a decent long jumper could have covered one side of the uncut trees along a creek in a single leap. On top of that I had an afternoon of hunting which flat-out frosted my grits. Fellow club members (not all of them by any means but at least one slob) had left litter scattered around two stands, abandoned a gut pile right where the deer died and insisted that best hunting practices included driving an ATV all the way to a stand. Combined with dogs running loose and what I considered some questionable (though legal) ethics, it was too much for me. I wrote a column for the local newspaper, calling no names but pointing out sordid practices in strong fashion.

A few months passed then the club’s president, who also happened to be an employee of a timber company, informed me: “Jim, we won’t be allowing you to renew your membership.”

Taken aback and for a moment speechless, I recovered my wits sufficiently to ask for an explanation. The best he could do was sort of hem and haw before saying “Some of us don’t like what you write.” He didn’t deny the truth of it, but in effect admitted that my words hit too close to home.

Looking back on that experience, I am convinced that I not only did the right thing but that far more folks need to speak out. In truth, no one who is a dedicated hunter or fisherman can afford to remain silent or take the path of least resistance, one which usually involves turning a blind eye. Instead, here are some suggestions on how to be proactive, feel good about yourself as an outdoorsman, and hopefully, in the end, make a difference.

1. Vote

For starters, vote, and vote like a sportsman. On all levels, from local elected officials on up the ladder to state representatives, congressmen, senators and the president, take careful measure of their stance on consumptive sports. Tell-tale points will include whether or not the individual holds a hunting or fishing license, his stance on the Second Amendment, how closely he is linked to support from anti-hunting groups, views on environmental issues. If a lot of red flags pop up, you have to wonder about voting for a particular candidate.

2. Voice Your Opinion

Beyond exercising your voting rights as a citizen, make your viewpoints and concerns known. One letter, e-mail, or phone call on a given issue might not make a difference, but rest assured if a politician is getting hammered by a lot of constituents most of them will sit up and take notice. If something you believe is of surpassing importance comes up, consider organizing a “contact our congressman” type campaign with hunting buddies, fellow club members or perhaps those in a local chapter of some conservation organization. It never hurts to let elected representatives know you are a vigilant watchdog keep close track of their voting record and what they are or are not doing to protect your rights as a sportsman. Incidentally, communication shouldn’t be limited to expressions of concern. If an elected official takes a stance you wholeheartedly approve, an “atta boy” just might get you a bit more attention the next time you have a complaint.

3. Invite Local Politicians to Experience Hunting and Fishing

Beyond vigilance as a voting citizen, there are other steps, many of them of a proactive nature, which you can take. For example, if you belong to a sportsman’s club or large hunt club which has an annual function in the form of a game feast, auction, banquet or the like, invite local politicians. Better still, especially if the individual doesn’t hunt or fish, extend an invitation to take them out to experience the joys of the hunt or the restorative pleasures of a day’s fishing.

4. Support the Sporting Community

Put a little of your money where your passion and your mouth are. Join conservation organizations, make donations to the campaign funds of pro-sportsman individuals seeking office, support groups that lobby or campaign for the rights of sportsmen, or otherwise commit a bit of time and/or money.

5. Mentor Youth Hunters

Don’t forget another useful step connected with passing on our wonderful sporting legacy. There are golden opportunities in the field of education. Today’s youth are tomorrow’s voters, but they aren’t necessarily tomorrow’s sportsmen. Do your part to offer them a chance to become hunters or fishermen. This can be as simple as hosting a youngster on an outing or two, speaking to a class, assisting in logistics or support for school archery or skeet clubs, facilitating youth hunts or any of countless other means of outreach. One of my favorite writers, Archibald Rutledge, left some timeless thoughts on the matter of educating and interacting with youth. “It is my fixed conviction,” he wrote (I’m altering his words a bit so they apply to youngsters in general as opposed to his three sons), “that if you can give children a passionate and wholesome devotion to the outdoors, the fact that we cannot leave each of them a fortune does not really matter so much.” For, as he continued, “I have a conviction that to be a sportsman is a mighty long step in the direction of being a man.” To those sentiments I would simply add a hearty “Amen” and amend his general sentiments to apply to females as well as males. If we can shape and nurture youngsters as lovers of hunting and fishing, we leave a truly meaningful legacy.

As sportsmen owe it to ourselves to counter the arguments and actions of those who assail our right (and it is a right, not a privilege, but one which should never be taken for granted) to hunt and fish. That means a willingness to stand up to those who assail the Second Amendment, determination to protect public lands and waters, devotion to preservation of habitat, backing strong laws and strong punishment for poachers and scofflaws who too often when caught receive minimal punishment, and ever keeping in mind that we are a distinct minority. Fortunately those who would end hunting and fishing as we know them are also a minority, but it is our duty, individually and collectively, to do our part to make sure the great bulk of the population who don’t hunt or fish understand and appreciate why we do and what we stand for.

In short, each of us needs, distasteful though it may sometimes seem, to be a political animal. That the reality of our world, and to ignore that reality is to invite calamity. I grew up in a place where posted signs almost were scarce as unicorns and in a time when no one gave a second thought to a small boy walking across my tiny hometown, shotgun tucked under my arm, for an afternoon of squirrel hunting. It was a time of simple days and carefree ways when boys carried a pocket knife as a matter of pride and practicality and when hunting belonged to the mainstream of daily life. That’s a world we have already lost, and it is up to each of us who cling lovingly to such memories and traditions to see it goes no further. We have to be political animals, at least to the point where we protect and perpetuate our sporting heritage.

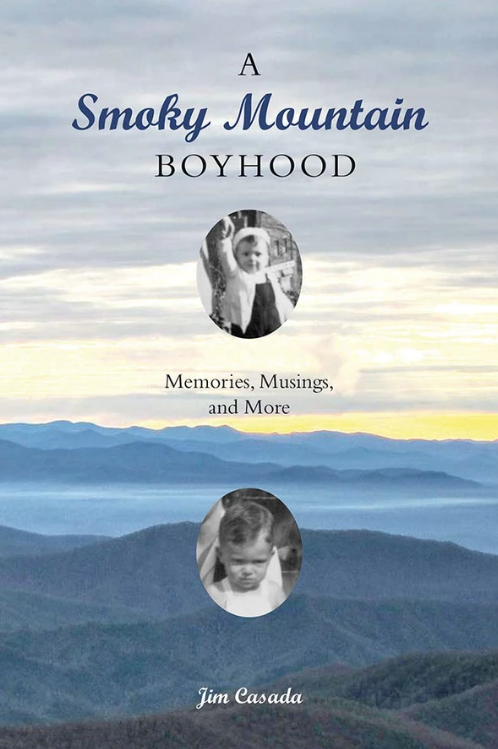

In A Smoky Mountain Boyhood, Jim Casada pairs his gift for storytelling and his training as a historian to produce a highly readable memoir of mountain life in East Tennessee and western North Carolina. His stories evoke a strong sense of place and reflect richly on the traits that make the people of Southern Appalachia a unique American demographic. Casada discusses traditional folkways; hunting, growing, preparing and eating wide varieties of food available in the mountain region; and the overall fabric of mountain life. Divided into four main sections—High Country Holiday Tales and Traditions; Seasons of the Smokies; Tools, Toys, and Boyhood Treasures; and Precious Memories—each part reflects on a unique and memorable coming-of-age in the Smokies.

In A Smoky Mountain Boyhood, Jim Casada pairs his gift for storytelling and his training as a historian to produce a highly readable memoir of mountain life in East Tennessee and western North Carolina. His stories evoke a strong sense of place and reflect richly on the traits that make the people of Southern Appalachia a unique American demographic. Casada discusses traditional folkways; hunting, growing, preparing and eating wide varieties of food available in the mountain region; and the overall fabric of mountain life. Divided into four main sections—High Country Holiday Tales and Traditions; Seasons of the Smokies; Tools, Toys, and Boyhood Treasures; and Precious Memories—each part reflects on a unique and memorable coming-of-age in the Smokies.

Containing a strong sense of adventure, nostalgic tone and well-paced prose, Casada’s memoir will be appreciated by those who yearn to rediscover the Smokies of their childhoods as well as those who wish to imaginatively climb these mountains for the first time. Shop Now