The First of April has for untold ages been the Day of Fools! Why? No one in particular seems to know. There are patron saints for everyone from the prelate thief, but who is the Saint of All-Fools?” Thus spoke Tom Marks, one of a merry trio of trout fishers who had journeyed up into Sullivan County, New York, to fish on the First of April, only to find that the waters of their chosen district could not lawfully be fished until the 15th of the month, and that they must journey many a weary mile across country before they reached a district where the open season began on All-Fool’s Day. The change of location was not accomplished until late in the evening and, although hopes were bright for the next day’s sport, there was considerable grumbling at lost time.

The party had gathered around the fire enjoying that peace that a pipe brings after a good supper, when Tom’s question was asked. In the corner of the fireplace was the oldest member of the party tying flies. He looked up: “Well, you boys knew all about it, and I left it to you until we were on the cars, but as soon as you said ‘ Sunny-side,’ I said to myself ‘Hoodoo,’ and, mind you, I had my reason.

“What were they?” chorused the other two.

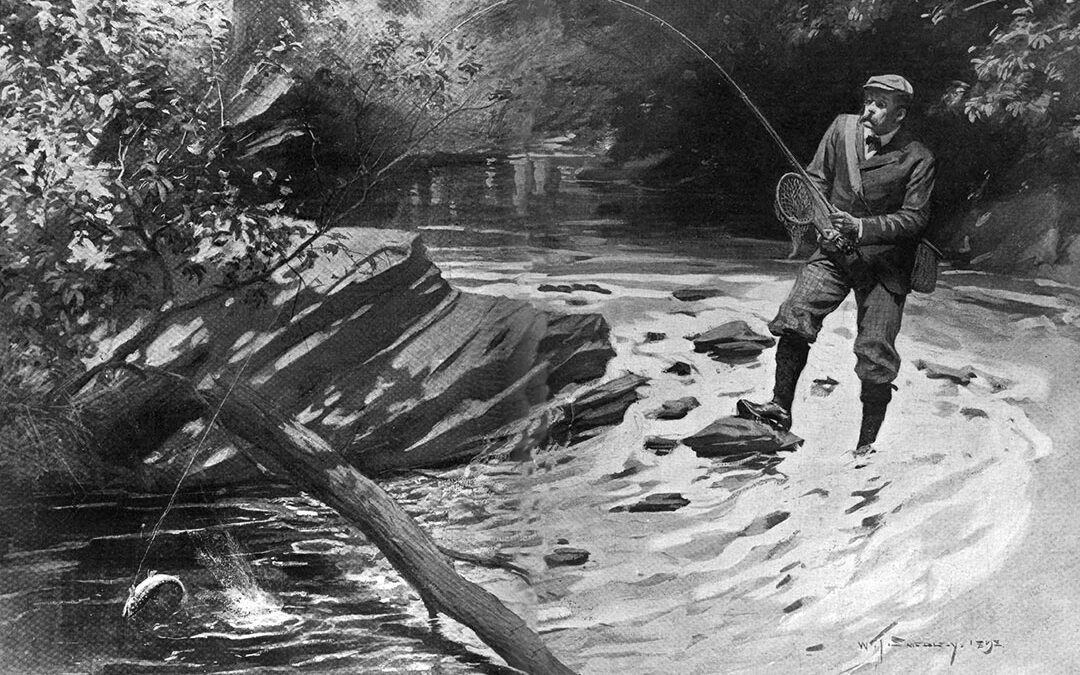

“A story now is as good as at any other time, and as we are properly April Fools this time (Heaven forbid that the boys ever hear of it!), I’ll tell you a story of 20 years ago, when I was fishing in this very county. I hired a man to show me the good spots, and he was worth his hire, for there was less open water than there is now, and I did not care for bait fishing. The next morning saw us off for the stream, and very good sport we had.

“My guide proved to be a quaint, garrulous fellow, who had lived up in those tangles for about 60 years and remembered plenty of strange happenings and changes. I drew many a yarn out of him at lunch and at nights. One day I was casting down by a curious old piece of ruined brickwork that looked as if it might have been built by Christopher Columbus and had been there ever since. Pat, the man, had gone into the woods to try and locate a patch of water he had lost track of, and I was to keep upstream until he overtook me. When he came along and found me seated on that brick wall, he nearly dropped and begged me to come away, adding that he had no idea I would get up so far or he would have been back sooner. Then he cussed at a great rate.

“We turned off to lunch, and this was the yarn he told me. The wall was part of a very old brick house, built during the British occupancy by an English gentleman, Pat’s father, then not long over from Erin, had acted as river warden, keeper, fisherman, etc. , to the Englishman, who was always fishing, never wearying of it as long as the fish were in season. What made both of them mad was that they always had to go some distance from the house to catch fish, for never a one was there in the pool opposite the lower garden wall. They put down two net dams, and put fish in between the two dams; but it was no use, not a fish could they catch. One day the Englishman got mad, and swore by the equivalent to the Great Horn Spoon that he would get a fish out of there if he fished until his arms fell off, and to that end he gave himself strength by loading up fairly well with whiskey.

“It was up the stream and down the stream, the owner and his man, first one and then the other, and as one bottle was emptied the servant fetched another, and no doubt took a sly nip on the way, and the Englishman’s eye (he was wall-eyed) seemed to glow with fire and obstinacy the more he drank, but otherwise he was as sober as a judge. Night fell, and still they were fighting the blank stream. The gentleman had fires built on the bank and made a night of it, notwithstanding that his good lady came down and begged him to come home, as a decent fisherman should; and there he fished until the dawn, while Pat’s father’s legs were like to drop off him with fatigue, or, more likely, to give under him with the whiskey.

“Still the Briton fished until at last, with a terrible oath he stood on the wall, just where I had been standing, and swore again that he would drain the blankety blank stream but what he would get a fish, and just then he had a magnificent strike and a run that made the reel buzz again. He was just commencing to play the big fish, for big it was, two or three pounds at least, when (so Pat’s father swore on the Good Book) out of the water rose a beautiful lady with a pronounced Hibernian accent, and said ‘I charg’ ye on yer p’ril to go ‘long outer dis ! The fishes in dis water is mine, an’ ye’ve no roight en loife ter ’em, an’, yer wall- eyed blayguard av de wurruld, git out av me soight, or it’s not tellin’ ye I’ll be,’ and then she dived into the water. The Englishman turned a little pale, but he kept on playing the fish, took another drink with one hand, and cursed Pat’s father that he did not bring the net quick enough, and just then his feet slipped on the wall, and in he went, down, down, down, into that deep hole. They dragged the water with rakes and hooks, but they never found the body. The lady shut up the house, went away and all the property went to rack, ruin and tangled scrub.”

“Well, that’s a great ghost story!” said Harry Myers, “what has it to do with the ‘hoodoo’?”

“I’m not through yet, boys. Pat swore that there was in that hole a freak of nature, ergo, a wall-eyed trout; that he was never to be caught, although he might be hooked; that he was the Britisher under the water fairy’s antiquated hoodoo, and that anyone who persisted in hooking him, went blind or died before the year was out.

“That settled it! I did not finish my lunch before I was up on the wall trying for that 100-year-old trout with the boss eye, and nothing Pat could say would shake me. For two hours I worked as never man did. I whipped every inch of the pool that I could reach from the wall, but without effect until, the light changing, I could see that one side of the hole terminated at the top in a slight overhanging ledge. I changed my fly for a white one with a golden tail, and deftly dropped it right over the apparent ledge.

“Ye Gods! with a mighty rush and a swirl, a giant fish took my fly and in a breath I could feel him hooked safe enough. How the touch thrilled down the tapering four-ounce bamboo, every section of it thrilling like a telegraph wire! To right, to left, up and down, backward and forward, a good fighter and a bold one. No subterfuge about him! Up to the top he came, and threw himself out of the water before my eyes, then down again to the depths, under the ledge and out again, but nowhere could he find a purchase on which to fret or fray the line, and still at his mouth the relentless tension of the line was sinking the barb deeper and deeper until the strain and pain together began to tell. I could feel him weaken. By that mystic intuition known only to the true fisherman, I knew that the end was coming, and that the beauty was mine by the prowess of my line and rod, as in the olden time by the sword and spear.

“Who said ‘Hoodoo’ to me at that moment? I had forgotten the wall-eyed Britisher, the water fairy, Pat, almost myself and my own existence, in the glorious battle of skill and finesse against strength and cunning. At last I bore a little harder on the line to bring him round. With a last gasp he turned from the butt, headed in a mad dying dash up the stream, and as I held firm to the line and reel with my thumb, he cleared the water with a mighty bound, and—the line snapped in the air like a whiplash—I had lost him! It did not seem possible, and I sorrowfully drew my leader up to my fingers—the fly, hook and leader were intact and whole as when new!

“Boys, I was paralyzed. Then a sound striking my ear, I turned, and there was poor Pat, rocking himself to and fro, crying and sobbing after the manner of his people: ‘ Ochone, ochone! Aw, the dear! Another av ’em gone! May the black shadder fall on the wall-eyed divil at the last day! Ow, Ow!’ I could not help laughing, in spite of my disgust at losing the fish and, packing up, we made our way back to the house, Pat refusing to be comforted.

“Next morning there was quite a levee outside to see the ‘man who was going to die or go blind because of the fish,’ for the tale was known in all parts, although I do not say that it was entirely believed. I was told of this man and that man who had all suffered something for their temerity, and when I wanted to go fishing, Pat refused to take me. ‘ Ye can’t put yer blud on my han’s, boss,’ was the way he put it.

“So I went by myself, and purposely fished up toward the wall, being determined to have another try for that piece of hoodoo bric-a-brac. Arriving at the pool I fished and fished, but only caught two small ones, and when about laying off for lunch, I saw a gleam of silver in the weeds at the other side of the water, 50 yards or so down the stream. The water was about 100 feet across, and to this day I do not know what prompted me to go casting for a dead fish, but I took off my fly and put on a fair sized bass spoon hook and at the second cast dropped it over the fish, and gently towed it across to my feet. It was my trout of the day before—dead—as dead as Imperial Caesar. There was something peculiar about this fish. Looking closely I could see that the front of the jaw, the round bone in which the hook generally holds, was clean gone, torn out years ago. The thin membrane remaining had a fringe-like appearance, and one eye was blind and gone, the socket being practically empty. This then explained the wild stories about the fish. He was wall-eyed, and he could not be hooked except in the lower jaw, and even then on very light tackle he would be very liable to break away, for he weighed three pounds and five ounces. But for his night and half a day in the water he would have made a very fine mounted specimen.

“So I lifted the hoodoo, caught the Phantom Trout, and am neither blind nor dead, and have no more idea how that gigantic lie ever got around in the form of an accepted and current legend than you have. But ‘Sunnyside’ was the name of the old Britisher’s place, according to Pat, and that was where our hoodoo came in yesterday and today. The story ought to lift it, and we will catch fish tomorrow.”

But we didn’t. It was bitterly cold, and sport was very poor. Our April Foolship was for keeps!

This article originally appeared in the May 1895 edition of Outing magazine.