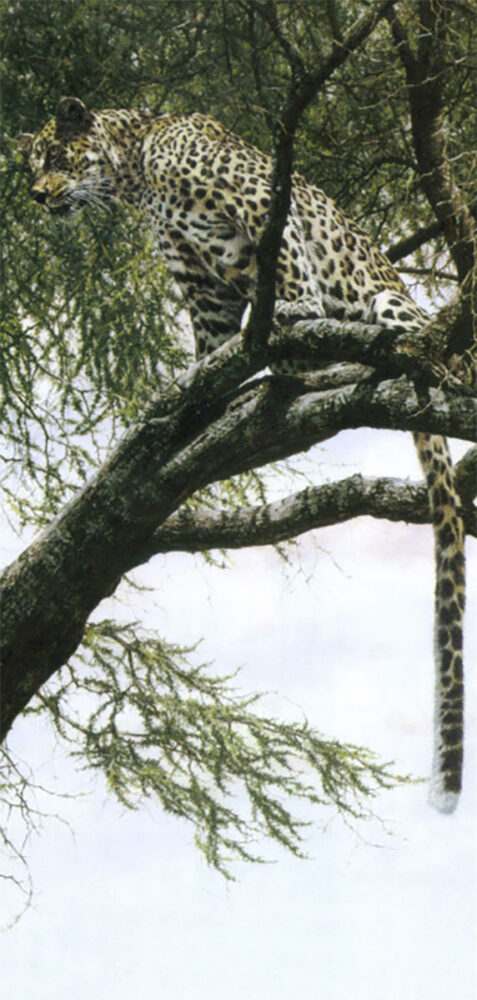

Webster was adrift in time again. For 30 minutes, or it could have been hours, the leopard fed.

The sun was setting behind the dangling bait, a shoulder from the zebra Webster had killed two days before. Forty yards away, Webster watched through a peephole in the grass blind as the last crimson streaks silhouetted the vertical line of the bait and the longer horizontal line of the limb from which it hung. They made a skewed black cross precisely in line with the place the sun had buried itself. Like Stonehenge, Webster thought. The sun over the heelstone at the solstice. Or like mistletoe. We hang a sacrifice from the sacred tree and await the spotted god. The image made him chuckle inside, but only inside, and the outside part of him stayed still and silent as the sunset.

When the light had gone and the leopard had not appeared, he and Christopher listened to the night sounds until the hunting car came for them.

“It was a big track,” Christopher said again as they drove to camp. “An old tom. We’ll by him again in the morning. You were steady in the blind? You could make the shot?”

“It was fine. I was thinking again about the zebra, though.”

“You don’t want to do that. Just think about the leopard, the angle he’ll be standing at, where you want to put the shot.”

“I know. The blind is so quiet I think it makes the ringing louder, so I start to replay the zebra, that’s all.”

“Ears still ringing, eh?” Christopher downshifted, snorted, grinned. “Not to worry. Leopards have nice spots to aim at — much better than stripes, you know.”

For Webster, hot showers spawned ideas in odd shapes that wandered the mental landscape almost, but not quite, randomly. Inevitably, if the shower lasted long enough, one of the odd shapes would tumble exactly right into the jigsaw hole that was the problem he had been worrying about. Now, hot water drizzled from the bucket hanging from the tree above the canvas tent. A lantern hissed nearby. Somewhere on the hill a baboon screeched obscenities— a leopard perhaps, just beginning his evening hunt. Maybe the big one we’re after. How big?

The water drummed against his head and the odd shapes began to tumble. Irresistible force, immovable skull, bits of Africa sluicing down, the bucket growing lighter, pulling less against the rope, over the branch, down to the tree, vectors up and down, the forces proportionate. Of course. The drumming slowed to a trickle. The shower had lasted exactly long enough.

The night chill raised goosebumps as Webster hurried to dress. A big moon, not quite full, cast soft shadows along the path to the evening fire. Christopher was waiting, his cigar lit, a beer mug on the table beside him.

“You really ought to use your flashlight, Webster. Puffadders, scorpions, safari ants … ”

“Oh, right. Sorry. Puff adders. I was thinking about the leopard problem you were talking about. How to measure one in the bush. You want to weigh it, but there’s never a scale, light?”

“Right. You aren’t just use feet and inches because people cheat. I’ve known professionals to cut the spine from inside just to stretch a decent cat into someone’s eight-foot monster. You weigh them if you can, which isn’t often. Usually you have to skin them before you can get to a scale. So you end up with these stories of 200-pound leopards, and maybe some of them are true.”

Footsteps approached in the darkness. Seth, the Camp’s headwaiter, materialized Jeeves-like in the firelight, bearing a frosted mug of beer on a silver tray.

“Asante, Seth.”

“Karibu.”

Webster took a long pull on the beer, and with a happy little grunt began the delicate ritual of cutting and lighting his cigar. He liked this, the small ceremony among the other small ceremonies of camp, surrounded by wildness and distance. “I think you can make a scale on the spot with a stick and some rope. Accurate to within a couple of pounds.”

“Mmmph. Sounds like something from the Boy Scouts. Got your leopard scale merit badge, did you?”

“When I was a kid, my dad had this book from when his dad was a kid. Two Little Savages. It was about a couple of boys camping out in Canada playing Indians. One of them was good at math and he used geometry to calculate the height of a tree without having to measure it.”

“There was a large Canadian leopard in the tree, I take it?”

‘Well, there was a lynx, but that was in another part oft he story. And you can go to hell. But there’s a connection: the kid was using proportionate triangles. If you have two of them and you know the size of one, you can calculate the size of the other one, right?”

“Mmmph.”

“Well, you can. So I was looking at the shower bucket on the rope hanging over the limb, and it made me think about how you could use proportions to weigh a leopard. You balance the leopard and something else from a stick, and the proportion between the lengths of stick on each side of the balance point is the same as the proportion between their weights. You with me?”

“Yes, actually, I am. It may be the beer. So if you know the weight of one side, you can measure each side of the stick and calculate the proportionate weight of the leopard on the other side.”

“Right.”

“Not bad. But what do you use for the counter weight?”

“Well, it could be anything, really, as long as you can weigh it later. Even a person.”

”We can by it. You’d better keep your weight up if we’re going to balance you against our big friend in the morning. Seth says dinner is ready. Shall we eat?”

But after dinner, alone in his tent with the sounds in his head, the zebra rises like a specter. His shot has gone badly. He knows it. Ears ringing, eyes following the zebra’s distant galloping form, his mind fixes on the moment just before the shot, the irretrievable moment. I should have held it, backed off when it moved. The images roll like frames in a slow film, the moment when the gunsight holds the quartering shoulder, and the next when it creeps light, wavering across rippling stripes into gut as the picture breaks up with the gun’s recoil. And now the zebra has disappeared over the hill and the last of its dust billows in the same wind that mutes the sound of the approaching hunting car, its own dust enveloping him as it pulls up, black hands clinging to the rollbar and the voices, “Piga! Piga!”

Yes, piga I know. Hit. But not well.

Christopher climbs from behind the wheel and stands on the running board. “He’s hit, but a bit far back I would say.”

“Yes. What do we do now?”

“We’ll see if we can catch him up.”

They trot quickly across the short grass where the zebra had fed, then more slowly into thornbush, eyes straining to see through the rough scrub. A flash of black and white ahead; the zebra is moving at a trot across an opening. Webster finds the zebra in the scope and swings ahead. OK, how far do you lead one as it breaks into a full gallop lead it lead it trying not to jerk the shots but each time knowing he has missed until there is only empty shimmering bush and the magazine is empty. The ringing in his left ear now is a sound he has never heard, a relentless howl on a Single pitch.

“Nothing, Christopher. Absolutely nothing.”

“No. I didn’t hear any of them Jut. He’s gone into the truck stuff. We’ll have to get the car.”

“The car? Is that all right?”

“He’s hit. We have to follow him, of course. I don’t think we’ll be able to see without the car.”

They retrace their steps and Webster climbs with the gun-bearers onto the bench behind the rollbar. The car grinds and smashes across scrub and heads into trees, plowing through eight-foot stalks of grass whose seeds explode like tiny grapeshot into his eyes. Too late the gun-bearers Signal to duck behind the cab when they hit the grass; Webster’s eyes are already streaming tears, the seeds gritty and burning as he blinks furiously to see.

The zebra is well ahead. They glimpse it briefly as it crests a hill or weaves between trees, still moving easily and yielding nothing to its pain. It could be mistaken for unwounded, whole, except in the fact that it can be seen at all.

The jolting twists through high brush change Webster’s sense of time and distance. He cannot say how long or far they have traveled, and if they have somehow circled to the place they began, it is still new to him. There is only the present, only this place. The chase is simply now, the zebra and car suspended at opposite ends of a single floating frame, connected only to each other and indifferent to the rest. His eyes are reduced to a stinging blur and the howl in his left ear is hammering this head. He could be swimming through the kind of deep-water dream that haunts the edges of sleep, the nightmare pursuit that is not any city’s legacy but the collective memory of the species from a time when all, and in this same terrain, were perpetually hunting and hunted. The grinding gears and crackling brush are the sounds of hell.

The jolting twists through high brush change Webster’s sense of time and distance. He cannot say how long or far they have traveled, and if they have somehow circled to the place they began, it is still new to him. There is only the present, only this place. The chase is simply now, the zebra and car suspended at opposite ends of a single floating frame, connected only to each other and indifferent to the rest. His eyes are reduced to a stinging blur and the howl in his left ear is hammering this head. He could be swimming through the kind of deep-water dream that haunts the edges of sleep, the nightmare pursuit that is not any city’s legacy but the collective memory of the species from a time when all, and in this same terrain, were perpetually hunting and hunted. The grinding gears and crackling brush are the sounds of hell.

Abruptly the car stops. The zebra is just visible as it stands on the edge of a wooded ravine. If it moves farther into the trees, the car will not be able to follow. Webster jumps down and is engulfed by grass and thornbush. The car is the only spot high enough to see over the thick bush, and even so when he climbs back up he can see only patches of striped hide that are nearly indistinguishable from trees and shadows. He struggles for a moment with a lifetime’s disdain, hating the car with a detached and furious clarity. So that’s the price. That there isn’t a choice. Our only chance now.

He wipes his eyes quickly and steadies the rifle on the rollbar, finding the shoulder in tangled thicket. He doesn’t hem’ the shot, but sees the explosion of bark and the whirling stripes heading into the trees and without thinking, almost without moving, and still adrift in time he works the bolt and finds the centerline of the neck and the zebra is tumbling and down before the ejected cartridge has stopped rattling on the floorboards.

“Piga! Piga mzuri!” and they are slapping him on the back and scrambling down from the car. He sits a moment, breathing, resting the rifle on his knees, staring into the middle distance. The sound in his head has not changed and he knows the sound will be there a long time, perhaps always. The images will hang there, too, as a moment hangs always in its place intime. That, too, is the price.

Christopher is looking up at him. “Nice shot, that last one. I thought we’d lost him. Shall we go take a look?”

“All right. Let’s go take a look.”

“Hello?” Webster’s head jerked on the pillow. Half-gagged in the middle of a snore he struggled choking to the surface, which was the dark tent and a repeated “Hello?” in the particular East African inflection that announces the arrival of morning tea.

“Oh, hello Jonas. Come in. Habari za asabui,” because he was working on his Swahili and because the words gave him something to focus on to replace the dream.

“Mzuri,” came the invariable response, a formula restoring order. Webster groped for the flashlight and took the mug from the proffered tray. The steam warmed the tip of his nose and the tea lit a warm trail inside him, pushing the dream aside.

Jonas watched for a moment, murmured “mzuri” softly again and began rustling among the things on the washstand. He set a fresh washcloth and towel beside the ewer of hot water, put the soap beside them, and padded backout into the darkness.

“Asante,” Webster called after him. “Asante sana.”Webster dressed quickly under the covers, washed his face at the washstand, fumbled with the toothpaste and his flashlight and stumbled out of the tent into starlight and a setting silver moon. Christopher was waiting in the dining tent.

”You slept well?”

“Oh, yes,” and it might have been true, after all; perhaps the dream had lasted only a minute.

“Good. Be sure to eat well this morning. Maybe some porridge with your eggs? Had a client out last year got so anxious he couldn’t eat. Big tom came into the tree on cue, all very nice, right? Walked past the blind, client’s belly rumbled. Might as well have cranked a chainsaw. Leopard jumped like we’d pinched his arse, landed somewhere in the middle of next month. Never saw him again. Have some more porridge and then we’ll go.”

They drove quickly for the first mile or two. The headlights picked out the bright red eyes of bush babies and once the sloped form of a hyena as it crossed the track. Christopher slowed as they approached the blind, the sound of downshifting gears stirring Webster’s memory, although it took a moment to identify it with the zebra.

No. Not that. Think about the shoulder, the spot just behind the shoulder. Don’t think about any of it, anyway … and they were there, slipping out quietly and into the blind, resting the guns in their corners, settling back on the canvas camp chairs as the vehicle eased away.

For a moment his mind was empty and all he knew was the night air pinch on his face, the weightlessness of starlight. To be the beginning, he thought. Not just at the beginning, but of it. This place. This time. Now. Maybe that’s the other side of the dream.

Christopher was leaning back in his chair. The starlight washed his face into a pale blank, with shadows for eyes. Webster imagined their faces floating side by side in the gloaming: twin shadowed moons in a grass-walled night, peering through holes into another world. He lost himself for a moment in the thought, and it was the sudden tensing in Christopher’s neck and shoulders rather than the sound itself that recalled him. The sound came again, closer: the deep, two-note ripsaw huh uh huh uh of a big leopard staking his claim. Then silence.

Webster thought he could feel Christopher’s muscles vibrating against the night, or perhaps it was the tension in his own spine and the strain of listening and trying to remember to breathe. Then without warning it was next to him, a faint rustling of grass and the light patter of soft pads on sand beside the blind, then silence again.

A minute passed, then another. A sudden scuffling at the tree made Webster start, then relax in warm relief. The leopard was in the tree. He hadn’t left after all, but had been sitting under the bait having a look. It would be all right.

Webster was adrift in time again. For 30 minutes, or it could have been hours, the leopard fed. Each stage had a distinctive sound: the crackling and crash as the leopard tore the protective branches off the meat, the scratch of claws on bark as it gripped the tree with one paw and ripped meat with the other, the wet crunching as it chewed. Soon it would finish, and unless dawn hurried, the leopard would leave before there was light enough to shoot.

Christopher had been watching with binoculars and now motioned Webster to open his peephole and get his rifle ready. Slowly, still reminding himself to breathe, Webster moved the barrel through the hole and rested his elbows on his knees. Through the scope the leopard looked faintly pink in the early light.

Webster looked at Christopher hunched against the blind with binoculars braced against the frame. Christopher turned, grinned and gave a quick thumbs-up and wiggled his higher finger to signal the shot. Webster leaned into the rifle and found the spot just behind the shoulder when the leopard turned abruptly, and looked left and right. Oh no, he’s going to bolt. Webster found the near shoulder — the forward angle this time — and squeezed.

He wasn’t prepared for the flash, a momentary image of the big cat’s silhouette flying backwards in a flashbulb halo, a leopard supernova, followed by darkness and the sound of dead weight hitting the ground. Then it was still in the blind. The pinkness overhead seemed to light another place entirely. A fragment of a poem played in Webster’s memory:

After the kingfisher’s wing

Has answered light to light, and is silent, the light is still

At the still point of the turning world

and time began to move again.

This book is the never-before-told story of the dream to set up camp in a vast African wasteland and return it to its former glory as one of the world’s premier wildlands. Buy Now

This book is the never-before-told story of the dream to set up camp in a vast African wasteland and return it to its former glory as one of the world’s premier wildlands. Buy Now