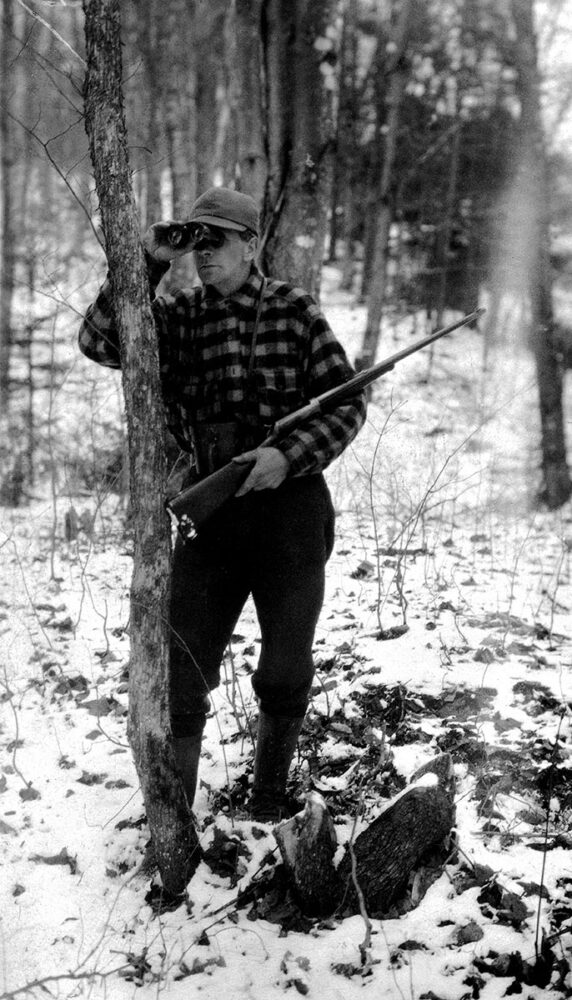

The air was cold and heavy with the promise of snow, and in the blue-black hour before dawn, I slipped across the creek behind our camp to the base of the mountain. After offering a silent prayer, I bolted a round, checked the safety, and started to climb. The initial ascent was the steepest, the kind of tough climbing that tests one’s resolve. But the quickening dawn urged me on, and I matched its tempo until I broke the third level. I knew this path well and soon found the old logging trail that led to the stony cut between hills, once coursing with spring melt, but long since dry. After some tricky footing, I reached the beginning of the acorn flats and greeted the dawn.

The air was cold and heavy with the promise of snow, and in the blue-black hour before dawn, I slipped across the creek behind our camp to the base of the mountain. After offering a silent prayer, I bolted a round, checked the safety, and started to climb. The initial ascent was the steepest, the kind of tough climbing that tests one’s resolve. But the quickening dawn urged me on, and I matched its tempo until I broke the third level. I knew this path well and soon found the old logging trail that led to the stony cut between hills, once coursing with spring melt, but long since dry. After some tricky footing, I reached the beginning of the acorn flats and greeted the dawn.

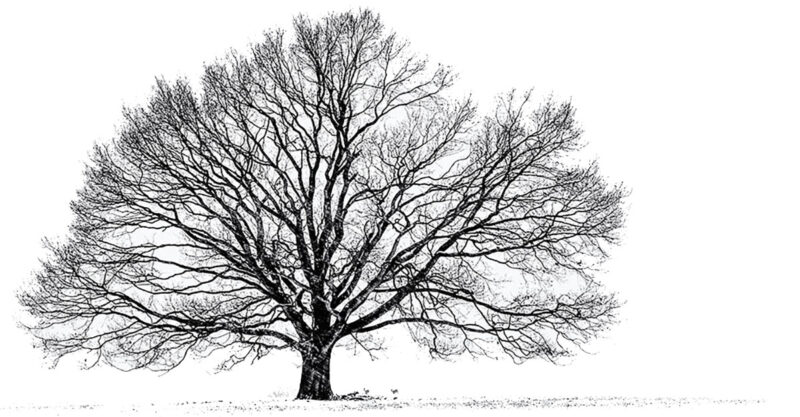

In the freshening wind, the dry canopy of stubborn oak leaves seemed to hiss at my intrusion. I slowly moved from tree to tree, watching, waiting, letting the timbre of the place resound within me. The paths inevitably moved higher, across grassy mesas flanking the blow-downs. Here, horizontal ash, bleached bone-white by the sun, was twisted into grotesque sculptures, embodying the finality of nature’s anger. There was a sorrow about this place, for here, through the brittle treetops, the wind would wail unique, mourning a dirge of lost possibilities, of things that would never be. It was a sound that once heard was never forgotten, and I always moved from there quickly, over the narrow saddle that eased into the west face of the big bowl, which crested before me in a panorama of blue, green and gray. This was the back pay I carried through the dog days of summer, etched in my mind as clear as the pale autumn air.

I glassed familiar areas one by one, looking for anomalies; horizontal patches of brown within the vertical green, flickering wisps of white … nothing. Carefully I eased into a shallow cut and over a small flat to the upper edge of the hemlocks. Forty feet down was a slight draw, imperceptible yet crucial to any passage from the ridge, for it offered the only route from the west face, cold and sheer, to the sunny beech flats facing southeast. Fifty yards off that natural funnel was my seat, by a gnarled and twisted oak, spiked with an ought-6 casing from the first shot I’d taken there some ten years prior.

I glassed familiar areas one by one, looking for anomalies; horizontal patches of brown within the vertical green, flickering wisps of white … nothing. Carefully I eased into a shallow cut and over a small flat to the upper edge of the hemlocks. Forty feet down was a slight draw, imperceptible yet crucial to any passage from the ridge, for it offered the only route from the west face, cold and sheer, to the sunny beech flats facing southeast. Fifty yards off that natural funnel was my seat, by a gnarled and twisted oak, spiked with an ought-6 casing from the first shot I’d taken there some ten years prior.

A slight breeze moving toward me set the beech tops in motion, their smooth-skinned branches back-lit and stark against the big sky, creaking every so often like an old porch rocker. I performed the customary housekeeping chores, scraping away tattletale leaves and twigs until I reached the quiet of the forest floor. I hug my pack, spread my Model 70 across a perfectly formed shooting bench of Catskill bluestone and settled in. The pre-season scouting I’d done had revealed some big work among the beech saplings along the outer reaches of the funnel. But I never scouted this area too hard. The topography was assurance enough.

I thought back to the casing in the tree, to a fifteen-year-old boy who should have known better. It had been an impetuous shot, taken when the shadows were too long, and a blood trail that carried me far from dinner was the lesser cost. In the falling darkness I lost that buck, and the twisted oak with its brass is my touchstone to humility, the realization that the greater levy can never be paid. Nor forgotten. It was a hard lesson, as those in these woods tend to be. Alone with my memories, the day wore on, minutes growing to hours, blue sky giving way to gray.

I thought back to the casing in the tree, to a fifteen-year-old boy who should have known better. It had been an impetuous shot, taken when the shadows were too long, and a blood trail that carried me far from dinner was the lesser cost. In the falling darkness I lost that buck, and the twisted oak with its brass is my touchstone to humility, the realization that the greater levy can never be paid. Nor forgotten. It was a hard lesson, as those in these woods tend to be. Alone with my memories, the day wore on, minutes growing to hours, blue sky giving way to gray.

And then I heard it, a slight snap in the maze of hemlocks. I stared at the green backdrop, trying to limit the movement it took to breathe. I actually smelled this buck before I saw him. Full into the rut and heavy with musk, he ghosted the edges of the hemlocks, and it wasn’t until the ridge shallowed that I got a glimpse of a front shoulder, rippled and huge. He slowly nosed out into the draw, head down in full sneak, and the size and mass of his rack jolted me into action. I quickly scanned the terrain. Thirty yards down the line of his path was the only window in the saplings and browse. I alternated between scoping the window and eyeballing the buck’s forward progress, gauging time and distance to the shot. Ten yards from the window he slowed, then raised up to check the thermals for any hint of danger, but the wind still worked in my favor.

The old adage “high low, low high” patterned through my mind, and I envisioned the crosshairs squared slightly low, behind the front shoulder. Ten more yards, five . . . I took a deep breath and squinted through the scope to see it fill with neck, then shoulder . . . hold . . . squeeze . . . Pow-wow-wow!

The atmosphere seemed to compress and expand all at once, as the report careened off the walls of the bowl and echoed back to me. The buck hopped straight up and then exploded in full flight, crashing through the branches in mortal desperation. I cycled the bolt, re-acquired the buck in my scope, and as he hesitated at the crest of a slight ledge, squeezed off another round. The buck dropped out of sight.

It had taken a total of ten seconds, and in the dreamlike aftermath, a stillness slowly descended upon me. My breathing rasped staccato holes in the air, now seemingly soft and heavy. Slowly, I replayed the events. It had been a good first shot, of that was certain, and the buck couldn’t have gone far. He was probably piled up in a tangle below me. I marked the initial point of impact, and after what seemed an eternity, picked up the trail. The shooting lane looked much smaller up close. On a backside sapling there was blood and a patch of hair; I’d hit him, but how well?

It had taken a total of ten seconds, and in the dreamlike aftermath, a stillness slowly descended upon me. My breathing rasped staccato holes in the air, now seemingly soft and heavy. Slowly, I replayed the events. It had been a good first shot, of that was certain, and the buck couldn’t have gone far. He was probably piled up in a tangle below me. I marked the initial point of impact, and after what seemed an eternity, picked up the trail. The shooting lane looked much smaller up close. On a backside sapling there was blood and a patch of hair; I’d hit him, but how well?

The story unfolded as I moved down to the ledge where I’d thrown the second shot. Droplets soon turned into a sprayed trail on the bluestone where I’d seen him last. Leaning over the ledge, I saw the prone buck, twenty yards beyond on a small beech flat. I slowly made my way down tile steep, cobbled path.

The footing was made tougher by the fact that I couldn’t take my eyes off this buck. Lying on his left side, his light beam extended more than two feet into tile air! As thick at the base as soda cans, his main beams swept out and upward in a high arc so common to bucks of this valley. His brow tines, at least eight inches in length, crowned a symmetry and mass that I had seen only in magazines. I could see where the bullet had exited, nicking his right shoulder, and when I lifted the rack and turned the torso, I found the entrance wound, three inches behind the left shoulder, dead on the heart; that explained the hop at impact.

I dressed and tagged the buck, and suddenly felt weak. It was if the electricity of the last fifteen minutes had surged and spectacularly peaked beyond the limits of its circuitry, leaving a void in its ebbing. I took a sip of water and struggled to regain my composure. Only then did I hear the snow, grainy and steady, falling on the leaves. This was going to be a tough drag. The wind started to moan ominous and low from beyond the saddle, a warning from the blow-downs. I needed to get off this mountain fast, and the thought of it paralyzed me. Not since I was fifteen had I felt this apprehension in the deer woods.

I dressed and tagged the buck, and suddenly felt weak. It was if the electricity of the last fifteen minutes had surged and spectacularly peaked beyond the limits of its circuitry, leaving a void in its ebbing. I took a sip of water and struggled to regain my composure. Only then did I hear the snow, grainy and steady, falling on the leaves. This was going to be a tough drag. The wind started to moan ominous and low from beyond the saddle, a warning from the blow-downs. I needed to get off this mountain fast, and the thought of it paralyzed me. Not since I was fifteen had I felt this apprehension in the deer woods.

And then, from within the hemlocks, I heard the sound of rustling leaves. I turned. Impossibly, on a mountaintop a long way from anywhere, I had a companion.

He was an older man with a look that hearkened back to the days of draft horses in logging rigs and two-man flat saws. Dressed in red-plaid wool and cradling a lever-action .300 Savage, he was a complete throwback. He pulled a pipe from his mackinaw and lit it, all the while carefully surveying the scene, moving only his eyes. There was a detachment in his manner, as if focusing on a far-off ridge. Finally he spoke.

“Was that you shooting up there?”

I nodded. He looked over the buck again, up to the ledge, and then into my eyes, calculating and assessing. He drew on his pipe and smiled.

“Good shooting, son. Need a hand?”

“I appreciate it, but I’ll be okay,”

I said, pride besting need.

”You sure? Don’t mind helping.” He glanced over his shoulder at the changing sky, and then down the mountain. “How are you planning on going down?”

“I wasn’t really, sure. Maybe the way I came in. Up over that ridge and along the backside of the valley.”

‘”Well, that’s certainly one way,” he said. “I’m sure a strong boy like you’d have no problem with the uphill part, but it still leaves you a long ways off.” He glanced back at the blow-downs and up into the flurries.

”You’re fightin’ time, son. There’s a storm coming on. Bad one, too. This is no mountain to get caught on. I’d go straight down that cut. Steep, but it’s all downhill and it’ll get you to the sawmill trail lickity-split. You can get help from there. And you best get going. That’s a mean wind, and she’s kicking. Sure you don’t need a hand?” I shook my head.

”You’re fightin’ time, son. There’s a storm coming on. Bad one, too. This is no mountain to get caught on. I’d go straight down that cut. Steep, but it’s all downhill and it’ll get you to the sawmill trail lickity-split. You can get help from there. And you best get going. That’s a mean wind, and she’s kicking. Sure you don’t need a hand?” I shook my head.

“Well, good luck,” he said, and slinging his rifle across his shoulder, he melted into the hemlocks and out of sight.

Alone, I considered my options. As if on cue, a single shaft of sunlight pierced the low clouds. Shining low and flat, it seemed to light a direct path down the stony draw, as if punctuating what the old man had said. So be it. I took a quick bearing, cinched my gear tight and started the long drag down.

It was then that the full force of the storm hit. The wind cut relentlessly, moving the treetops to impossible angles, an unseen hand holding me in this maelstrom. Through its roar, I could hear the crashing of branches. The snow quickly obliterated all contours, and the ankle-grabbing shards of hidden bluestone gave each step hard consequence.

My cargo became an added source of frustration, for its rack seemed to hang up in every furrow and scrub, its tines extracting a measure of revenge as they jabbed my hamstrings with every forward tug. There was no use in fighting it, for there was no recourse. Surrendering to the unknown, I turned my shoulder into a wall of spindrift and dragged on. An hour later, soaked and exhausted, I had beaten the darkness to the base of the mountain. One hundred yards ahead lay the creek and just beyond its banks, was the road to camp and the salvation of a roaring hearth.

I decided to mark the buck, then go onto camp solo. I’d come back, with help, and save myself a tough drag on flat ground. In the muffled, swirling gloaming, I headed home. The old man had been right. I just wish I’d gotten his name.

That night, through what was turning out to be quite a storm, the boys and I piled into town for a celebration of sorts at Al’s Bar and Grill, the migratory point for more than two generations of hunters that slept late, whether they’d earned it or not. News travels fast in deer season, and in these hills, good fortune is a commodity always shared. The dim light in the bar added to the drama of my story, highlighting the somber expressions of my audience, for everyone agreed that I had more than my share of luck on this day. I omitted all mention of my mountaintop encounter. In retrospect, the route home seemed so obvious, why look like a fool? As the crowd around our booth cleared, only old Jim Crawford remained. He fixed me with an owlish stare and pointed his finger.

That night, through what was turning out to be quite a storm, the boys and I piled into town for a celebration of sorts at Al’s Bar and Grill, the migratory point for more than two generations of hunters that slept late, whether they’d earned it or not. News travels fast in deer season, and in these hills, good fortune is a commodity always shared. The dim light in the bar added to the drama of my story, highlighting the somber expressions of my audience, for everyone agreed that I had more than my share of luck on this day. I omitted all mention of my mountaintop encounter. In retrospect, the route home seemed so obvious, why look like a fool? As the crowd around our booth cleared, only old Jim Crawford remained. He fixed me with an owlish stare and pointed his finger.

“Luck had nothing to do with you gettin’ off that hill!” he said. I froze.

“I was in that same bowl some forty years ago when a bad one hit, just like today. The far side of that mountain’s got a thousand ways to turn you around, especially in a white-out. If it wasn’t for an old friend, I think I’d be up there yet. You’re a good woodsman son, and killin’s got nothin’ to do with it. Any fool can pull a trigger.”

He jerked a thumb at a wall full of pictures. ”The boys’d be proud. You took what the mountain was throwin’ at ya and kept your head. Ain’t nothin’ lucky ’bout that.” He winked. “Good job.”

But I knew better. Old man Crawford was right about one thing; the fact that I came out smelling like a rose had everything to do with good judgment. Just not mine. I had been on the verge of making a mistake with big consequences and had gotten lucky running across the old-timer on the hill. Real lucky. He’d even offered to help me, and I’d repaid his kindness with arrogance. I needed to find the old man and make amends. I smiled, for it occurred to me that he had taught me two lessons this day.

But I knew better. Old man Crawford was right about one thing; the fact that I came out smelling like a rose had everything to do with good judgment. Just not mine. I had been on the verge of making a mistake with big consequences and had gotten lucky running across the old-timer on the hill. Real lucky. He’d even offered to help me, and I’d repaid his kindness with arrogance. I needed to find the old man and make amends. I smiled, for it occurred to me that he had taught me two lessons this day.

It was time to go. While waiting for the jeep to warm up, I lingered by the photos that serve as a backdrop for the memories shared in this room. There, in the middle of the wall, was a faded black-and-white picture of old man Crawford’s gang, gathered around a meat pole in an old mountain camp. My heart jumped. In the middle of the group was a familiar mackinaw.

“Bill, who’s this guy in the plaid?” I asked the bartender.

“Bill, who’s this guy in the plaid?” I asked the bartender.

“That’s Jake Armour. Owned the old textile mill here for years. Big woodsman and a gentleman. Quite a guy. Damn near a legend among the old-timers. Why do you ask?”

“Just like to thank him, that’s all.”

“Have to go to Warren Ridge to do it.”

The next afternoon, in the gathering mist, I made my last hike of the season, one that I have repeated every year since, to this day. For on the outskirts of the mountain hamlet, there is a forlorn knob of meadow, ringed by wrought iron and briar, forgotten, abandoned. It is a long walk from here to there, a very long walk indeed. The gates to the old Methodist cemetery have long since lost their defiance. More to contain, I now believe, than to ban, they lean indifferently to either task. I slip between them easily and filter through the graves of Warren Ridge. So many patches in this quilt. A loving wife, a son lost to war, a family consumed by fire as they lay sleeping. Lives gone to ash, the grist of all headstones. I find Jake Armour, beneath the spreading limbs of an oak tree, marked by a simple stone that bears his name. There is an epitaph:

The next afternoon, in the gathering mist, I made my last hike of the season, one that I have repeated every year since, to this day. For on the outskirts of the mountain hamlet, there is a forlorn knob of meadow, ringed by wrought iron and briar, forgotten, abandoned. It is a long walk from here to there, a very long walk indeed. The gates to the old Methodist cemetery have long since lost their defiance. More to contain, I now believe, than to ban, they lean indifferently to either task. I slip between them easily and filter through the graves of Warren Ridge. So many patches in this quilt. A loving wife, a son lost to war, a family consumed by fire as they lay sleeping. Lives gone to ash, the grist of all headstones. I find Jake Armour, beneath the spreading limbs of an oak tree, marked by a simple stone that bears his name. There is an epitaph:

For the wind, the salt wind, the sea wind,

For the wind, the salt wind, the sea wind,

Is beating a cloud through the skies;

I would wander always like the wind.

And so I sit, solitary, awaiting the unmistakable sound of rustling leaves.

This story originally appeared in the Jan/Feb 2003 issue of Sporting Classics.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Featuring both fictional and true-to-life adventures, these astonishing stories are from the creative minds of such legendary authors as Peter Capstick, Archibald Rutledge, Gene Hill, Mike Gaddis, Roger Pinckney and John Madson. Buy Now