Good covey dogs are, as Lincoln said of Civil War generals, “as plenty as blackberries.” Hardy, spirited rangers that will put up whatever there is to be put up and give you your money’s worth day in and day out. That is, in good bird country.

But if you are ever fortunate enough to get your hands on a real single-bird dog, don’t forget to say your prayers regularly. It’s the only thing I’d steal without the slightest compunction of conscience—a really good one.

For a covey dog, give me a pointer—stamina, dash, derring-do. For a singles dog, give me a setter—patience, thoroughness, precision. Just one man’s experience, and if it doesn’t jibe with yours don’t sue me for it. All you could get would be covey dogs, anyway. Single-bird dog is in my wife’s name.

Also, if you care to, you can give me a setter that has been spayed. And I’ll take my setter with a little age on her. Rare old Ben Franklin advised a young man to pick an old woman to have his affairs with. The same consideration underlies my nomination of an oldish lady for singles hunting.

To carry the specifications a little further, you can give me a slow dog, one that has plenty of time. There’s no such thing as a fast singles dog and a good one.

Funny thing, too, I never saw a good singles dog with a fancy name. A friend of mine has a sedate and aging setter whose name is Bess, but whom we always refer to as the Old Maid, which just suits her mincing delicacy and fastidious thoroughness in the field. The Old Maid is not in the canine Who’s Who. She has never been in a field trial, nor had her picture in the papers. And you have never heard of her. But I know a couple of hard-headed hunters who wouldn’t trade her for a first cousin of the Grand Champion, once removed. Will Carrington is the other fellow. In fact, the Old Maid really belongs to Will, although he always refers to her as “ours.” I have mainly a borrowing interest in her.

In golf, you drive for fun and putt for money. In bird shooting, you hunt coveys for excitement and singles for your game. This is truer now than ever before.

Time was when birds were so plentiful that covey hunting would give a man all that he wanted, and more than he was decently entitled to. I reckon such a time once was. If not, the old-timers I’ve listened to are a raft of unhallowed prevaricators.

I know a whimsical old gentleman who is fond of saying: “I ain’t the man I used to be. Never was.” Maybe it’s that way with birds.

Time was when Bob was a self-contained and chancy fellow who held his ground until properly flushed. But he is not so stable as of old. He has become a bit jumpy here of late, often flushing at the least provocation. In fact, latter-day Bob is fast becoming an ungentlemanly trickster, full of sly ruses and pettifoggin’ ways. Or, to put it kindlier, Bob has developed a bad case of the DTs. And pray who wouldn’t have, what with the “reclamation” of his refuges by a benevolent and misguided Government, the encroachments of a more scientific agriculture, and a highly mobilized Coxey’s army a-gunning for him day in and day out?

But for his 20th-century nerves and growing slipperiness, he would have lost out in the unequal battle. Bob has learned that discretion is the better part of valor. His philosophy is not unlike that of a roguish old darky who “tote de game” for me and always gives as ample reason for running out on a free-for-all-fight: “Cap’n, I’d druther hear ’em say, ‘Cain’t dat nigger run!’ than hear ’em say, ‘Don’t he look natchul.’”

For good and sufficient reasons, then, the singles dog is coming into his own. And sometimes local weather conditions join other factors to make such a specialist a prime necessity.

For instance, in low-country South Carolina, where I pay a few taxes and shoot a lot of birds, the 1939 hunting season opened in the middle of a drought. There had been no rainfall for more than two months. Fields, woods, even the devilish bays were as dry as tinder. Leaves rattled ominously wherever you stepped. There had been no rain to dissolve the dust from the undergrowth, and our dogs were forever sneezing and coughing. Trailing conditions were next to impossible. As the season advanced, the drought became more pronounced, and the birds more jittery and unstable.

Two Setters by Percival Rosseau.

Of the 38 coveys that Will and I raised during the first week, 27 flushed prematurely, slithering away at the first approach of the dogs and holing up in the impenetrable bays, where few bird hunters and no gentlemen will follow them. Singles hunting proved equally disastrous. The dogs would either run over the ground-hugging singles in the dusty straw, or flush them in the powder-dry, clattering leaves. It was not the fault of the dogs. Good hunters they were—Jackie, Pedro, and High Pocket. Just too fast for dry-weather hunting.

During that unhappy first week, Will and I had one experience that will warm the cockles of any bird hunter’s heart, however old and hardened a sinner he might be. A whopping big covey roared up from a pea patch ahead of us and sailed away to a field of golden broomstraw. They didn’t clump down in a body, but deployed nicely in two’s and three’s. As perfect a layout for singles shooting as a body could wish.

“That’s the sort of thing that keeps a fellow huntin’,” Will grinned. “The sort of thing that don’t happen too often in this here modern society.”

“Sure looks like the payoff,” I agreed. “And the answer to the bird supper that we’ve invited all those people to.”

“Yes, sir,” seconded Will as we strode confidently toward the field; “if a fellow can’t fill his pockets with such a layout as that, he’d better quit.”

But our hopes were short-lived. While we were still a hundred yards away, birds began to pop out of the dry straw and head for the distant and forbidding bay. We started to shout at the dogs and run—which a good bird hunter seldom does much of. But to no purpose.

Sweeping through the straw, our dogs routed those singles one by one. Even respectable dogs will sometimes lose their heads when things are popping too fast. When we got there, not a blessed bird was left. What can take an unruffled and philosophical spirit and tear it to tatters like that?

“And that’s what makes a fellow quit huntin’, I reckon.”

Will slumped forlornly on a log. “Twenty birds in that covey, and we got how many? Nary a one!”

“Pretty thorough job they made of it,” I added dismally. “We hunted for that chance a whole week, and had it ruined in two minutes.”

“Straw too dry.”

“Dogs too fast.”

“Birds nervous.”

Thus we tersely diagnosed the case, and Will added the clincher: “Ain’t goin’ to be any better until it rains, and”—he looked toward the discouraged skies—“it ain’t gonna rain no more.”

“We got to do something about it,” I ultimatumed.

“Yeh. Got to,” Will dully agreed.

“What you got in mind?”

“Nothing.”

I chewed a sassafras twig and wondered if I could put a notion in Will’s head without his suspecting my authorship.

“By the way,” I said, trying hard to sound honest, “how old is the Old Maid?”

“She’s pushin’ eleven.”

“Too old to hunt, of course.”

“Yeh. Too old.”

“Fattish, too, I reckon.”

“Yeh. Fattish, too.”

“We agreed last year not to hunt her any more, besides.”

“Sure. Shook hands on it and promised Mary.”

“Never do to lie to Mary.”

A pretty satisfactory conference, I figured, knowing Will as I do. And when we met the next morning, there was the Old Maid in person, an amiable old blue-ticked Llewellin, squatting like a fat dowager on the front seat of the car. And there was Will, looking happy and sort of sheepish.

“Got her, but had to stand for a lot of kidding from Mary. Said we ought to be ashamed of falling back on an old pensioner, us with our $200 dogs. But my pride is gettin’ easy to swallow here lately.”

“Of course, we’ve got to favor her,” I conceded, fondling a shaggy ear.

But it was soon apparent that the Old Maid would do her own favoring. Quietly she trotted behind us, contenting herself with an occasional excursion to check up on a likely thicket or a tentative clue that the other dogs had found and abandoned. Nothing could induce her to try her fortunes with the rollicking trio that swept the fields ahead. The Old Maid knew why she had been brought along, and she knew her own limitations, which is about the finest thing either dog or man can learn.

Within half an hour the other dogs had raised a fine covey, the birds flushing wild as usual and sailing off into an overgrown field.

“Now let’s call those rambunctious hellions in, tie them to a sapling, and let the Old Maid speak her piece,” decided Will.

So saying, he produced three lengths of rope and tied up the traveling trio, much to their disgust and the jeopardy of the sapling.

The Old Maid had seen the covey and watched it down. As we approached she trotted sedately ahead of us and began to insinuate herself through the undergrowth. Step by step she minced along, sneaking through the dry weeds and straw like a ghost. “Walking on pins and needles,” Will called it. And presently she announced a single, which Will brought down and which she retrieved with the same daintiness, carefully retracing her steps on the retrieve to prevent invading untested ground.

“Notice how she came out the same way she went in? Old thing doesn’t mean to risk a flush,” beamed Will.

“I don’t need a guidebook to the Old Maid’s virtues, thank you,” I answered, and bagged the next bird myself.

Back she went unbidden to her task, tiptoeing tediously about, warily testing every clump of weeds for her high-strung quarry. Once she pointed a single with a bird in her mouth, a heartwarming sight however often you have seen it. And once again she brought in a twosome—not to be dramatic, but because common sense dictated such a procedure when two birds lay side by side.

When her tedious job was done, bless my soul if the Old Maid hadn’t pointed and retrieved nine of those singles without a mishap or accidental flush!

English Setter By Edwin Megargee.

One of her traits that had particularly struck me was her quiet self-sufficiency. Not once had she let her anxiety to retrieve betray her into rashness, as might well have happened with a less-practiced hand. Not once did she require instructions as to her job. We never talk much when the Old Maid is on a hard case. Matter of fact, she never thinks such a touchy situation appropriate for idle chatter. When a bird was downed Will simply announced the fact. In him she had complete faith, never requiring reassurance and never relaxing her quest.

That very thoroughness of hers cost us an hour’s delay the next day and gave me a sidelight on Will’s training methods. Will has a way of his own with dogs, and the incident, although a trifle irritating at the time, was highly revealing.

A wing-tipped bird had scurried into a hollow log and baffled the Old Maid’s efforts to extricate it. Valiantly she laid siege to that log, prying, scratching, and jamming her muzzle into the hollow, but to no avail. Nor did our added efforts help any. I tried to talk her into resigning the case, but no amount of persuasion could induce her to abandon the beleaguered quarry.

“We can’t do anything with that derned dog, Will. We’ve lost fifteen minutes already. Tell her to be reasonable and come on.”

“Just against her principles to leave a wounded bird, I reckon,” replied Will.

“Heck! Pitch another one near the log and let her retrieve that. Maybe that’ll satisfy the fussy old dame.”

“That would hardly be honest, would it?” demurred Will. “A dog should be taught not to lie. Best way to teach ’em that is not to lie to them. I taught her that same thoroughness when she was a puppy, and I’m not goin’ to fuss with her now. She’s right and we’re wrong, only she has more time than we have.”

With that, Will smiled indulgently and stalked off across the field. A quarter of an hour later he was back with an ax and a wedge, and we fell to splitting that log so that the Old Maid could satisfy her conscience.

“That’s what comes of having too good a dog,” I chided peevishly. “And damned if you ain’t as stubborn as she is.” But in my heart I felt a sneaking admiration for the pair of them.

For the next four weeks, as long as the dry weather lasted, we followed the same procedure: letting the other dogs hunt the coveys and the Old Maid the singles, especially when conditions called for delicate maneuvering. They were altogether the most restful and satisfying hunts I’ve ever had. And three-fourths of the birds we bagged during that time we owed to the patience and finesse of the old lady.

“That dame is a genius, and nothing else,” I conceded after a particularly fine day. “Just as an academic question, Will: What will you take for your half of her?”

“Well, there’s my car, my gun, and the other dogs. There’s the farm, the mules, and the kitchen stove. And there’s my wife, maybe. But the Old Maid, I reckon she’s about the only thing on the place that ain’t for sale.”

“Think I’ll put her in a story,” I ventured.

“If you do, be sure to say she ain’t for sale.”

“No dogs like her nowadays, Will,” I insisted, caressing a ragged ear. “Sometimes I think that nothing is as good as it used to be, anyway.”

“Oh, you’re just getting mellow over your shootin’ these last few days. Matter of fact, that puppy I’m workin’ on now will be just as good as the old lady in time. It’s not hard, if a fellow has the patience, time, the birds—and a dog to start with. But unless a man is cut out by Providence to fool with dogs, I reckon he’d better hire his trainin’ done. Best money he ever spent. Or buy one already trained. If he’s an important fellow that gets off just now and then, he’d better buy a dog that’s set in his ways, an old dog that’s got more sense than he has—one he can’t ruin. And I don’t mean any harm by that. A fellow has got to be out of a job and not worried about it to train a dog right, I reckon.”

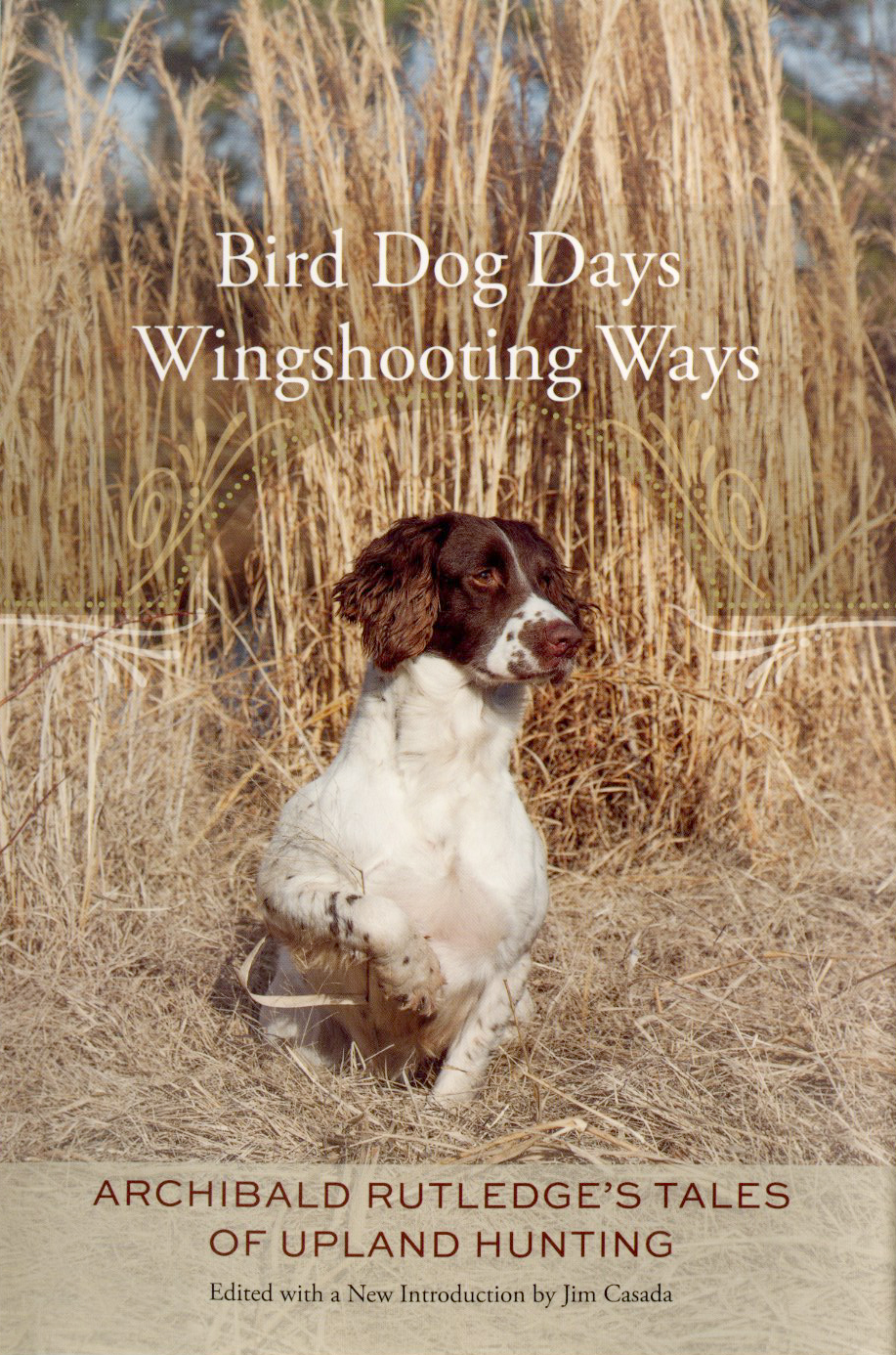

Bird Dog Days, Wingshooting Ways

Click Here to Learn More

This collection, first published in 1998, turns to Rutledge’s writings on two subjects near and dear to his heart that he understood with an intimacy growing out of a lifetime of experience—upland bird hunting and hunting dogs.