“From the very beginning, being an artist was my first choice.”

You can tour the most discriminating galleries, visit the most thoughtfully-curated exhibitions. As you walk these clean, well-lighted places, you stop, as much from duty as interest, to study the artwork on display. Some will leave you cold, like a draft you turn your back to. That’s simply the nature of the beast called art: It’s subjective, risky, the artists speaking languages you may, or may not, be capable of interpreting. Others, because of their visual impact and emotional content, will earn your admiration. In a few, you may detect the spark of genius. But rarely — very rarely — is a piece of art so original in concept, so striking in executions, that it stops you, as if by physical mastery.

Stroncek ‘s Brook Trout became the 1988 CaliforniaWild Trout Stamp and Print. Unlike most conservation stamps, which typically reflect simple, tightly rendered designs, the 6 x 9 1/2 acrylic is more like a miniature painting, loosely conveyed and with several key elements. Transparencies for this and other images courtesy of the artist and Wild Wings, In c.

There was a painting in the 1989 Birds in Art Show at Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin, that possessed this kind of presence. It was impossible to ignore. Called Ahead of the Storm the acrylic-on-canvas depicts a small flock of snow geese migrating by moonlight, racing the weather. Obscured by scudding clouds, the moon is a smear of light. The wind buffets the birds into a ragged wedge; they appear pale and fragile against the enormous, dark sky. The treetops bend, the clouds contort into swirling, dreadful masses. The dramatic contrast between dark and light is evocative of Turner; the swirling effects reminiscent of Van Gogh. It is a painting felt as much as seen; you remember nights like this, the wind an intruder rattling at the window, the thin wail of geese fading in and out like the memory of a dream until you quit the warmth of the house to search for those distant voices. You find them, either by ear or by eye, and wonder at their tenacity, their singleness of purpose, the mysteries locked behind their lives.

Van Gogh and Turner do not often come up in conversations about wildlife art, but Lee Stroncek, the man who painted Ahead of the Storm , is no longer content to follow the crowd. He wants to explore fresh territory, the high country of art, where a misstep spells disaster. With Ahead of the Storm, a work clearly outside the mainstream, he worried that the public might not be ready for such a radical departure. He was taking a chance, and he knew it. “It wasn’t the first time,” declares the soft-spoken, 38-year-old Stroncek. “I can’t play it safe anymore. It doesn’t satisfy me.”

Quietly, patiently, without hype or hoopla, Lee Stroncek has made a name for himself. The route has been arduous, with success a matter of perseverance and dedication, not of luck. Stroncek’s recognition has been hard-won. He has crafted a solid reputation and fashioned a loyal following.

“Collectors call us all the time,” says Kathy Sposita, manager-director of Hole In The Wall Gallery of Ennis, Montana, “and ask, ‘What do you have by Lee. Stroncek?’ Last July, we displayed 30 of Lee’s new paintings and invited 350 people from across the country to a private champagne reception. It was a total sellout.”

The Osprey’s Nest, a feeling of nostalgia that is found in virtually all of his paintings of people.

By strict definition, Stroncek is not a “wildlife” artist. It is more appropriate to call him an “outdoor” artist, for while his canvas includes animals, it also encompasses sporting scenes, depictions of camping and canoeing, nostalgic vignettes of family activities such as Christmas tree cutting and berry picking, underwater portrayals of trout and salmon, and pure landscapes. “Variety keeps me interested,” he confesses. “A lot of different things strike me as potential subjects for paintings. They’ re usually outdoor-oriented, though.”

Art and the outdoors have always pulsed at the heart of Stroncek’s life. He grew up in the shadow of Minneapolis, but spent countless hours at his grandparents’ home near Leech Lake in the Minnesota northwoods, fishing, hiking, and coming to love the lake country. His father and grandfather were avid sportsmen who indoctrinated Lee to the joys of stream and field . Stroncek’s mother, a graduate of the Minneapolis School of Art and Design, worked as a fashion illustrator at Dayton ‘s, the famous department store. She encouraged her son’s artistry by bringing home the tools of the trade: brushes, pencils, pen nibs, ink. The boy’s aptitude was obvious to family and teachers alike. He drew the objects of his fancy, filling notebooks with ships, tanks, cars, airplanes- even the faces of comely women.

“From the very beginning,” he recalls, “being an artist was my first choice. But everyone kept telling me how tough the competition would be, and how difficult it was to earn a living. I wasn’t sure I could do it.”

Influenced by self-doubt, Stroncek decided to pursue his passion for the outdoors and become a wildlife biologist. He enrolled at the University of Montana, transferring a year later to the University of Alaska.The mountains, wildlife, and seasonal pageantry of the West enthralled him, but his progress towards a degree sputtered to a halt. For one thing, he couldn’t fathom the advanced mathematics the curriculum required. For another, it became clear that employment opportunities in the wildlife sector were few and far-between, with the promise of long hours and low pay. Stroncek had continued to draw and paint whenever he wasn’t frying his brain in the skillet of differential calculus. Suddenly, a career in art seemed like a pretty attractive option.

Indian Creek Crossing reflects Stroncek’s enthusiasm for painting light and for joyful, impressionistic colors.

Thus began Lee Stroncek’s odyssey. He worked an interminable stretch of part-time and temporary jobs, including stints with the Forest Service and UPS. He bused tables in restaurants, ran a ski lift, nailed furniture. All the while, he was determined to establish himself as an artist. Stroncek’s wife, Janet, was the family’s primary breadwinner, but more important was her unflagging spiritual support. Stroncek took art classes, concentrating on figure drawing, at Colorado State. The cruel realities of the art business were made plain when he tried selling his paintings at street fairs. “Every Tom, Dick and Harry who walked by thought he was an art expert,”Stroncek laments. “I got more insults than I did sales.” The occasional assignment for an advertising illustration trickled in, but his Colorado address minimized his marketability as a commercial artist. He tirelessly made the rounds of galleries, placing the odd painting, and steadily mailed transparencies of his work to sporting magazines, hoping for a break.

In 1979, the Stronceks moved from Steamboat Springs to Bozeman, Montana, where they still reside. The change made all the difference. It was as if he had been navigating for years through a dense fog, a fog which, for no discernible reason, lifted to reveal a horizon shimmering with possibility. Finally, he was able to realize his dream and devote his labors entirely to art.

“Moving to Bozeman was a turning point,” he allows. “I was pretty much at a dead end in Colorado. Things just started to happen when we came here — I don’t exactly know why.” He knew his fortunes were on the ascent when Fly Fisherman reproduced one of his paintings. “It was a pretty big deal for me at the time,” he admits.

There is a timeless quality to Stroncek’s In the Lake Country.

Early on, Stroncek discovered a niche doing underwater scenes of fish in their natural habitat. He refers to them as “underwater landscapes”; they have a diorama-like quality about them. Via observation and photography-much of it accomplished on his favorite trout stream, the Gallatin River-Stroncek learned the ways in which colors change when light is filtered through water, and how fluid, even abstract, the riverine environment appears. His ability to combine accuracy with a painterly touch led to a significant commission from Trout Unlimited to depict all the North American salmonids. The paintings ultimately accompanied a series of articles in Trout magazine on the natural history of these species. (Lately, Lee has taken a vacation from this subject matter. “I did so darn many,” he relates, “that I was running out of variations.”)

Another boost to Stroncek’s career occurred when he signed on with Wild Wings, the big print-publishing house in Lake City, Minnesota. This partnership exposed his art-and his name-to the broadest possible audience. And it was through Wild Wings that another fruitful association took root. L.L. Bean was looking for an artist to do its calendars and catalogue covers. Wild Wings suggested Stroncek, and a match was made. “They gave me a lot of freedom,” he enthuses. “For two years I was basically my own art director. The nostalgic theme was my idea-it fit right in with the romantic, ‘northwoods’ image they wanted. Of course, I love all that stuff. I’d waited forever for a chance to paint like that.”

In virtually all of Stroncek’s compositions that include people, the nostalgic element is present. His sportsmen wear plaid wool mackinaws, battered felt hats, and boots that lace to the knee. They cook over open flames, bivouac in canvas tents, propel cedar and-canvas canoes with white ash paddles. “From prior to the turn-of-the-century until the early ’50s is what I consider the classic period,” he says. “After then, the equipment, to me, doesn’t look right. I don’t want to put aluminum canoes, nylon clothing, or splashy colors in an outdoor painting.”

Stroncek’s style, too, harkens back to that timeless era. He is a painter of light, not a fussy renderer of line. His handling of paint is loose, joyful, almost impressionistic. He is far more interested in conjuring a mood than in making a statement. His is an accessible art, one that invites the viewer’s participation.

“Compared to any other contemporary artist that I’m aware of,” says Kathy Sposita, “Lee is completely unique. He has a classic, old-fashioned style that’s never outdated. It’s lasting. There’s a softness, a warmth to his paintings. He puts so much feeling into them; you don’t just look at one of his landscapes, you enter them. You respond emotionally. Trends and fads in art come and go, but Lee sticks with his own style. I think that’s important.”

The warmth of Stroncek’s paintings reflects his own personality. “Lee’s not a materialistic man,” notes Sposita. “He’s not out to cash in. Some artists get arrogant after they’ve experienced success, but Lee is humble, caring, and down-to-earth. He’s just a peach of a person.”

Not surprisingly, given his nostalgic bent and his emphasis on the traditional, Stroncek’s list of favorite painters reads like a Who’s Who of sporting and wildlife art. “I honestly admire an awful lot of artists,” he stresses, “and I’ve gained something from each of them.” Parenthetically, he adds, “I’ll admit that most of them are deceased.” Excitement creeps into his voice when he begins speaking of Sir Edwin Landseer: “one of the geniuses of animal painting,” and Winslow Homer: “the best American watercolorist, except possibly for John Singer Sargent.” He reels off the great names: Thomas Eakins, Wilhelm Kuhnert, Percival Rosseau, A. Lassell Ripley, Oliver Kemp, Phillip Goodwin, Roy Mason, Ogden Pleissner. A lover of mountains himself, Stroncek expresses a particular fondness for the way Carl Rungius portrayed the Canadian Rockies: “No one has ever done them better.”

And while there are contemporary artists he hugely respects — he mentions T.A. Daly, Bob Kuhn, and Bob Abbett — the achievement of the “old masters” remains his lodestar. “I don’t know if there will ever be artists to match them again,” he muses. “I can’t see anyone coming up to their standards.”

When he’s not in his studio — 8:00 to 3:00, usually — Stroncek can be found outdoors. He prefers fly fishing for trout to all other sports, but enjoys hunting for pronghorns and mule deer as well. Winters, he cross-country skis, though he roams the high country year-round.

Year-round, too, he stays alert for ideas that may contribute to his art. It might be a specific location, a peculiar slant of light, an arresting juxtaposition of shapes or colors. He describes the process of making a painting as “bits and pieces that come together.” The camera is his tool for recording the images that resonate-but photography is just a tool. “There’s too much ‘verbatim’ painting,” Stroncek charges, “too many paintings that are obvious copies of photographs. You can see it right away; the shadows are black and colorless.” His approach-the one employed by virtually all artists worth of their salt-is to blend the actual photographic reference with the inclinations of the imagination, and construct a believable, affecting whole.

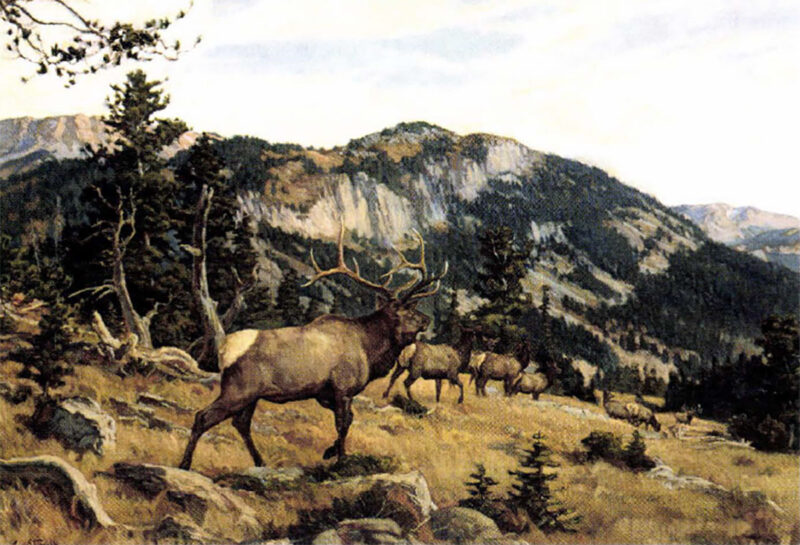

In his wildlife paintings, Stroncek takes pains to ensure that the animals appear as natural components of the overall landscape, not as overwhelming, frame-filling presences. “That’s how I’ll see a bird or a mammal. It’ll just be a glimpse, or they’ll be off in the distance, or camouflaged.

Logan Pass

“So much wildlife art falls apart when you remove the animal. The quality of the landscape isn’t there, or it doesn’t measure up to a fairly well-done animal. To me, the most important part of a painting is getting the proper environment; then, the animals can be worked in any way you want. I always look for the landscape first. Then, I figure out which species I want, and how to portray it. The sky, the mountains, the trees, the creeks; they’re as exciting to me as the wildlife. Sometimes I can’t wait to get the animals done so I can work on the landscape! That’s where I really have fun.”

These days, Lee Stroncek’s goals have nothing to do with recognition or career advancement. They have everything to do with improving his art. He wants to become more painterly, more impressionistic, although he concedes that the public expects a certain level of concrete reality in wildlife art. He wants to experiment with subject matter: night scenes, winter-scapes. He hopes to exert subtler control over his colors: the challenge of incorporating color into moonlit compositions (like Ahead of the Storm) intrigues him terribly. But most of all, he wants to paint light. The pinks and roses of alpenglow are irresistible to him, as is the constantly changing mosaic of clouds, sky, and mountains. “You could paint that for the rest of your life,” he attests, “and not even scratch the surface.”

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now