Down in the southwestern corner of Arizona, well away from the commoner farings of miners and teamsters, lies a desert tract of land all but inaccessible, and certainly uninviting. From one’s very feet the chalk-like floor stretches away to the far-distant skyline, its lonely monotony seldom broken by the dun-colored sage or the reddish rocks. He is the wise traveler who goes well out of his way to avoid its extremes of heat and cold—and the countryside yet awaits the genius who may render the crossing not comfortable, but reasonably easy.

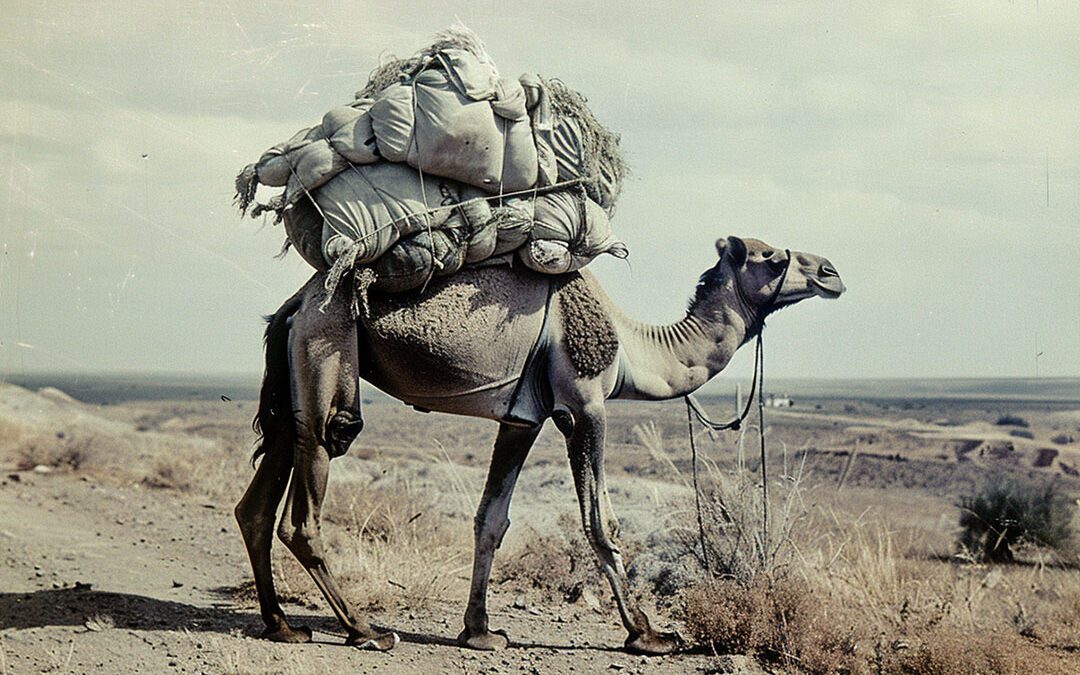

The government of an earlier day made some such attempt, bringing hither about two score camels for military and postal service, but the experiment failed brilliantly, and Uncle Sam joined the ranks of the unsuccessful, leaving his camels to the usual and unenviable devices of strangers in a strange land. They wandered at will through the hills that border on the waste, startling lonely prospectors, stampeding the horses of hunting parties or, in

cold-blooded deviltry, devastating the fields of an isolated rancher. Now and then one was shot or captured, but the fittest survived to find their way to the more hospitable regions that lie along the Upper Salt and Gila rivers.

Some even traveled over into the San Francisco valley, there to live in the camel’s substitute for clover. The most vindictive camel ever foaled could afford to forget past wanderings and woes, once he had set foot on the verdant carpet of those fertile plains that reach gently up to the woods that separate the great snow-capped mountain peaks from their less pretentious brethren of the foothills.

It was in this fair land that we had camped, just at the edge of a little clump of birch that linked the open to the pine woods. Our immediate foreground, as we sat facing the river, or rather, as much of it as we could see in the fast-fading light, was enough like Connecticut to have made at least two of our party homesick, had they been inclined that way, and the breath of the needle-carpet, just above, must surely have whispered “New Hampshire” to that other whose capital had been largely invested in our prospecting. But the stars in the heavens and the very atmosphere that wrapped us ’round was California, while the whole wide West might well have been personified in the grizzled little man who guided our wanderings by day and usually beguiled our evenings with ultra-vivid tales of local murder and sudden death.

That particular night—and though the ashes of our campfire have lain cold beneath the snows of 11 winters—I can still recall each small incident in his story that was almost as new to him as to us. The week before he had been down on Blue River where a rancher had treated him to the yarn and several whiskies. As the hospitable gentleman referred to had himself heard the story only one or two removes from its initial source, it would have been a flagrant breach of Western etiquette to have doubted its truth.

It would seem that, only a few nights before, one Samuel Crouch, a thoroughly respected citizen of those parts, and an abstemious gentleman, moreover, who had not had a drink for at least three hours, was coming out of the brush when there rushed past him in the gathering a great tawny beast ridden by something.

This word something, with its fascinating, Poe-like suggestiveness, was used advisedly it would appear, for Mr. Crouch stood ready to make affidavit, and yet more ready to take several sorts of oaths that it was not a human being. There were no screams, no cries, no sound whatever ’til the great creature reached the fringe of bushes, and then nothing, save their own crashing evidence that the vision had been one of this tangible world.

Mr. Crouch’s story, as retold to us, was a trifle incoherent, and stirred the very depths of interrogation in some of us, but the narrator stood by his guns stoutly, adducing detail upon detail as if to strengthen his position by the mere weight of words. Finally, he clinched all with the assertion that he, at least, was no doubting Thomas, and that if it was not one of Crouch’s own stock, wandering from the straight and narrow path, then it was the ghost of Jesus Villegos out for a ride under the stars.

This was but tinder to the already laid train of our curiosity. The old fellow needed very little urging to the telling of this Villegos, artistically embroidering the edges of the oft-told story with an easy skill that was only equaled by the picturesque vernacular in which he talked. Both are beyond me; I can only give the gist of his yarn, which called us back to the days of the Apache Chatto.

This enterprising chieftain, with a generous following of his gentle subjects, had, so the story goes, crossed the San on his way to Sierra Madras, leaving a bloody trail for the troopers to follow. Many ranchers were killed, their buildings burned down and their stocks scattered. When the raiders reached the Blue River, they came across old Thinston’s sheep ranch, which is, or rather then was, the biggest in the West. The manager had got wind of their probable call just in time to clear out, and there was little to prevent their enjoying an extremely big time at the expense of the firm. They had it! —and when they had gone on to hunt up the next man, back came the manager to reckon damages.

There were three dead bodies lying in the smoldering ashes of the huts—for the tip that had saved that manager’s scalp had not come in time for him to spread the news with any remarkable thoroughness, but one of the hands was not to be accounted for, even in so gruesome a fashion. Jesus Villegos, a Mexican ranchhand, never turned up.

For a day or so, no one thought much about it, but as the weeks slipped past with no news of him, his acquaintances began to talk more and more of the Apache fondness for torturing prisoners, and at last it came to be regarded as a mere matter of fact that Villegos had been carried off for the tribe’s further amusement—and that is how Jesus Villegos came into the mind of our guide.

As was to be expected, the missing Mexican became at once the topic of our discussion, and several solutions of the mystery had to be offered and debated. But as the evening wore on, the exertions of the day began to assert their rights and gradually the talk dwindled and died—as perhaps Villegos had.

Some hours later, when the fire had subsided to a mere glow, a huge animal tore through the camp, scattering the embers among our startled and half-awakened party, and stampeding our stock. Before a shot could be fired, it had vanished, and so suddenly that its very passage might have been doubted but for a scream, seeming not of this earth, which came faintly to our ears as the apparition crashed down through the brush in the dark canyon of the river.

The apparition after that appeared frequently. The Mexicans called it “La Phantasmia;” the whites named it the “Red Ghost.” Everyone dreaded it, everyone was curious for a sight of it. At last, someone saw it by daylight plainly, and that same evening, at the town bar, reported that it was only a camel with a bundle of some kind tied on its back. Incredulity and contradiction raged high and long over this, the only direct piece of evidence that had as yet been adduced, and the question remained as far from settled as ever.

Then a lone prospector at work near Chace’s Creek came upon it while it was grazing, and taking a shot at it as it galloped off, brought down part of the bundle—a man’s bootleg from the knee down! Thereupon speculation grew apace, and Villegos was resurrected and so firmly bound in public opinion upon the back of that rambling camel that the only wonder was the very pain of it did not bring him back to life.

All this ended one evening when a cowboy, torn and bleeding, was carried into the frame building that did duty as hotel. His mates had found him lying near the outlet of a blind canyon in the foothills. Before another day passed, he went on to join the silent majority, but consciousness had returned to him long enough for him to tell his story.

He had been out on a round-up on the hills of the Upper Gila, where he had unintentionally trapped the Red Ghost in one of those little canyons that a Frenchman would call a cul-de-sac. In an attempt to escape, the beast had charged him, but swinging his pony aside and back upon his haunches, he had avoided the rush, firing his revolver into the creature’s body as it passed.

Aroused by the pain and with its wicked-looking eyes wide open and its neck outstretched, the Red Ghost had turned on him, and as he fired again, had struck his horse in full force, knocking both it and its rider to the ground. The rage of the beast must have been demoniacal, for maddened by the wounds it had by this time received, it had torn the man’s side and thigh terribly.

That La Phantasmia was to blame for the funeral expenses incurred by the town was certain, for even had there been two of the quondam government beasts in the neighborhood, it stood to reason that but one should carry so ghastly a burden.

In the course of another fortnight, a skull with some coarse black hair still clinging to it had been found and brought in, and later still, some arm bones, scarce held together by shreds of dried skin.

Parties were organized to hunt the beast down, but in vain. Their horses were no match for the quarry, especially when he took to the tracts of

loose-lying sand, and all that was gained was exercise and the knowledge that the rider had disappeared.

One morning at early daybreak, a ranchman dwelling on Eagle Creek woke to discover a big, awkward, sand-colored animal in his little potato patch. The end of La Phantasmia had come. He had committed his last offense against the laws of civilization. He and his mystery were at last to be examined at close quarters. Resting his Winchester upon the windowsill, the ranchman brought the creature down on his first shot.

Wound and twisted over the back and shoulders were strips of rawhide and buckskin, in twists and fastenings that no white man would tie. He studied over one of the arrowhead splicings for a moment, and then went in for his knife. He had evidently solved the mystery to his own satisfaction, for as he returned he was muttering something about Apaches.

So was the mystery of Jesus Villegos solved.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the September 1900 edition of Outing magazine.