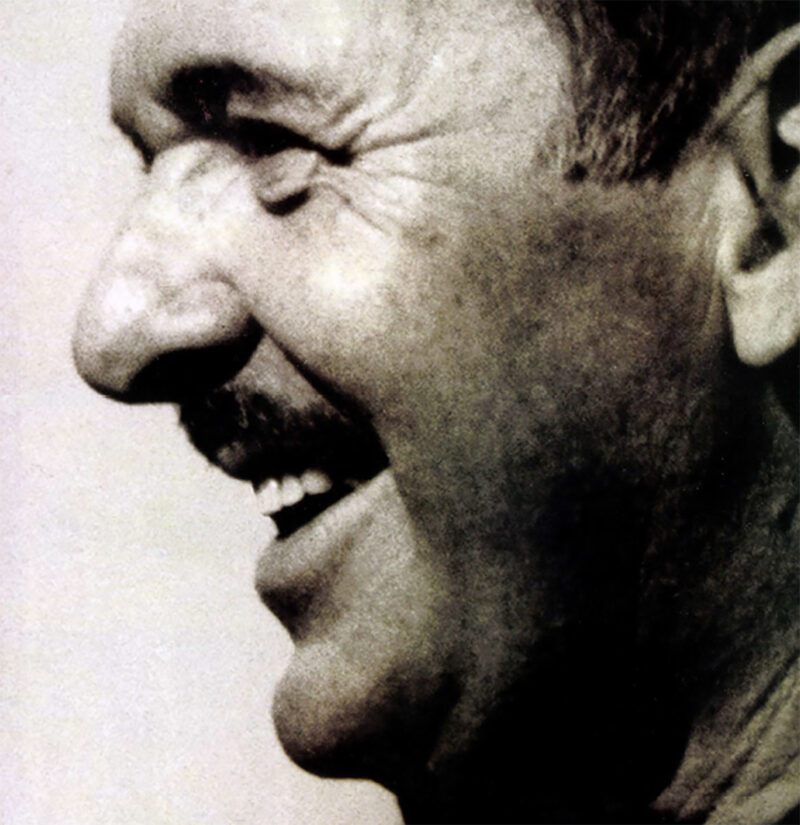

“…the most incredibly wonderful, generous, humorous and likable son of a bitch who ever lived.”

To many discerning readers, Robert Ruark ranks as the finest outdoor writer ever to grace the American literary scene. His enduring fame is linked to three immensely successful books: The Old Man and the Boy, The Old Man’s Boy Grows Older, and an African classic, Horn of the Hunter. Ruark wrote several blockbuster novels, and he was a very popular newspaper columnist, a satirist of considerable skill and a tireless bon vivant. Fame and the ability to crush out a prodigious amount of first-rate prose on his battered portable typewriter brought him considerable fortune, as is exemplified by his castle in Spain and his 1955 Rolls Royce.

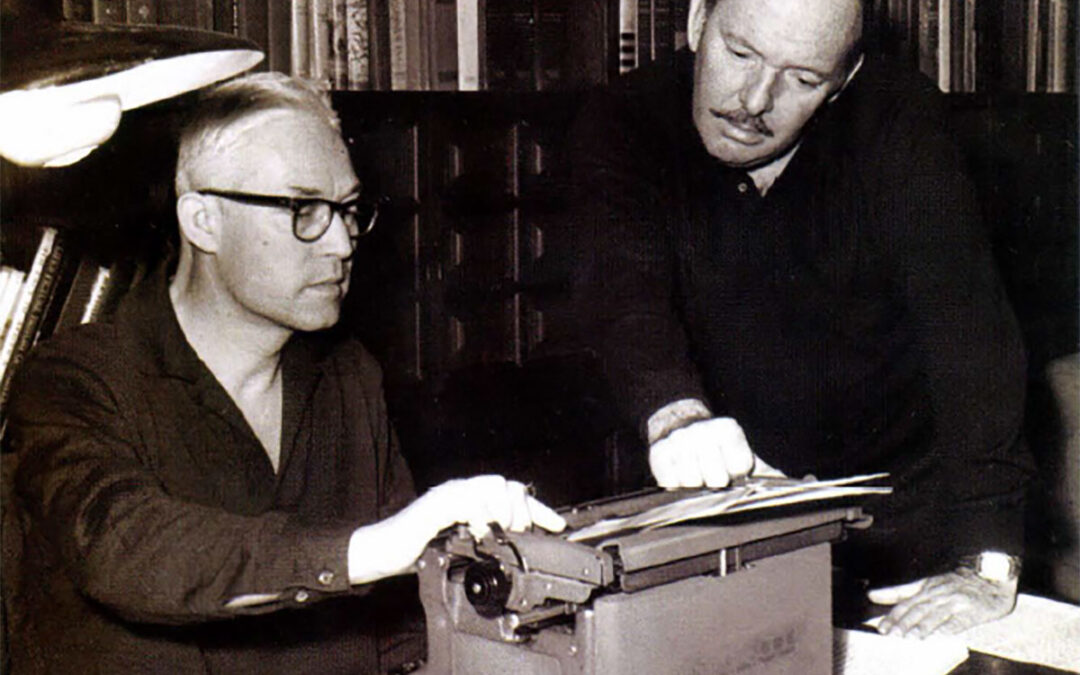

Alan M. Ritchie (aka “junior”)

Yet, in many senses, the story of Ruark’s life is a sad, cautionary tale and despite something of a minor cottage industry in biographies and anthologies focusing on his career, he remains somewhat of an enigma. He committed suicide with the bottle just as surely as Ernest Hemingway did with the pull of a trigger. As a boy and man, he was part of a tortured and dysfunctional family. He epitomized chauvinism run amok; his marriage was a mess, he was a wanton womanizer and in his later years he could only write when several sheets to the wind. No wonder students of his life, and I belong to their ranks, have found it difficult to come completely to grips with the man who was really Robert Ruark.

Even Ruark himself, in a noble but ultimately inadequate attempt at introspection, gave us little more than hints of his complex persona in “The Man I Know Best,” first published in True magazine in 1963 and then reprinted in my 1996 anthology, The Lost Classics of Robert Ruark.

Now, an extraordinary “find,” hidden From posterity for a full two generations since Robert Ruark’s death, promises to shed new light on the writer sometimes known as “the poor man’s Hemingway.” This amazing discovery is a detailed, insightful biography of Ruark written by Alan Ritchie, who served as his secretary, general factotum, occasional chauffeur, and what the English sometimes describe as a “gentleman’s gentleman.”

Alan Ritchie was an Englishman whose first career was as a sergeant in the British army. The two met in 1953 in Spain, where both men had traveled to escape the hurly burly of city life. Ritchie had been there since 1950, having joined the staff of a cork manufacturing company, but after a few years he became disenchanted with the position and began seeking a new job.

In August, 1953, a serendipitous meeting Ritchie describes as “complete chance” led to his being hired, on the spot, to become Ruark’s personal secretary. The impulsive act, one that typified Ruark, proved to be a godsend to the expatriate American’s career.

Thus began, on a sunny Sunday afternoon, what Ritchie characterizes as twelve years of a fascinating association with the most wonderful employer and friend.”

From the outset, Ruark and Ritchie were a splendid working pair, although the latter does acknowledge that “towards the end … I lost him to some extent in a confused haze of alcohol and women.” The two men got down to business immediately and began a serious working relationship, something that had eluded Ruark through a long series of female assistants he’d employed. The women, who were invariably attractive, either fell in love with their macho employer or earned the wrath of his wife, Virginia (or both), so Ritchie was a welcome change.

Helping to prepare Ruark’s book on the Mau Mau situation in East Africa, which would be published as Something of Value, was Ritchie’s first major order of business. He also had to deal with a six-month backlog of correspondence, make arrangements for Ruark’s purchase of and move into a castle in Palamós, and perform myriad daily chores. Among those duties were overseeing “house building, customs processing of trophies, tree transplanting and earth moving, driving … to Rome once a year in order to legalize car papers and handling everyday chores quietly and without a fuss.”

A behind-the-scenes, albeit important, role for Ritchie was to serve as a sounding board and stabilizing influence to his boss, and in general, to “make it easier for Bob himself to be a writer.” Ritchie was also expected to stay sober (something that was not always easy in the Ruark household), be the soul of discretion and look after Ginny when Bobby was away.

Ritchie was by nature a quiet, soft-spoken introvert, a self-described “natural-born listener,” and these characteristics were ideal counterfoils for the boisterous, extroverted Ruark.

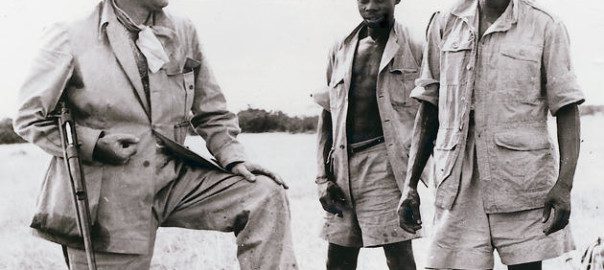

Bobby Ruark (aka “father”)

As the years passed, a number of coincidences would draw the two men closer to one another. Both had suffered wounds to their left arms during World War II and both brought a genuine honesty to their dealings with one another and with life. In time a truly special bond linked the men. Ruark eventually adopted the habit of calling Ritchie “junior,” while Ritchie in turn began to refer to his employer as “father,” even though only four years of age separated them. According to Ritchie, this affectionate term was something the childless Ruark “seemed to rather like.”

Ruark periodically refers to Ritchie in his factual narratives and does so with warmth, but he reserved his most affectionate tribute for one of his novels. Luke Germani, the erstwhile major domo to Alec Barr in The Honey Badger, represents Ritchie just as surely as Ruark himself was the model for the lead character.

Ritchie would accompany Ruark on one African safari. He would come to know all the highs and lows of interacting with this mystifying, mercurial and often magical man. Certainly, Alan Ritchie had a far greater impact on Ruark than has heretofore been recognized. He couldn’t supply the genius; that was uniquely Bobby Ruark’s. What he could and did offer was a constant, much-needed dose of practicality, helping the renowned author to function when gin threatened to drown his genius or when wanton prodigality seemed a harbinger financial ruin.

In Ruark’s adult years, no man was ever as dose to him as Alan Ritchie. He understood the troubled, talented writer; he served him in a capable, admirably loyal fashion and he left us a deeply moving, insightful record of his employer.

Following Ruark’s death in 1965, Ritchie, a lifelong bachelor, continued to live in Palamós until his own passing in 1982. Then, fittingly, he was buried in the town’s municipal cemetery, only a few short steps from the final resting place of the man he had served with such fervent loyalty.

Ritchie wrote his biography in the years immediately following Ruark’s death. Its working title, “A Long View from a Tall Hill,” comes from the title Ruark had chosen for a book he never wrote. His manuscript covers all of Ruark’s life, though it primarily focuses on the years when Ritchie was actually in his employ.

Along with offering posterity the fullest account yet of Robert Ruark, one based on firsthand knowledge of the man and his milieu, the biography has two other noteworthy features. Harry Selby, the legendary professional hunter under whose tutelage Ruark sampled and savored the wonders of Africa, wrote a Foreword for the book. Likewise, North Carolinian George Saffo, who knew Ruark personally, visited with him at Palamós and played a key role in obtaining this manuscript and ensuring that it would see the published light of day, provided an Afterword.

Alan Ritchie, the man who unquestionably knew Bobby Ruark best, says his goal was to record “an honest biography of a much-loved personage.” He talks of giving a “definite impression” of the man he describes as “the most incredibly wonderful, generous, humorous and likable son of a bitch who ever lived.” In truth, he has provided Ruark aficionados with more than a definite impression. Ritchie left us with the nearest thing to a definitive impression of the Old Man’s Boy we will ever have.

The heartwarming sequel to the best-selling The Old Man and the Boy is a moving, nostalgic tale that will transport the reader back to a time when going fishing was not about fish, but the stories told afterward. Buy Now

The heartwarming sequel to the best-selling The Old Man and the Boy is a moving, nostalgic tale that will transport the reader back to a time when going fishing was not about fish, but the stories told afterward. Buy Now