The gruesome exploits of the maneaters, together with those of Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson…form one of the most fantastic tales in the annals of African adventure.

In the 1890s Britain’s far-flung empire covered a quarter of the globe, including a number of strange, out-of-the -way places. Of all its territories, perhaps none featured more geographical diversity than the vast reaches of British East Africa. This newly-acquired territory, which had been explored by one of the great names in African discovery, encompassed the sultry, clove-laden island of Zanzibar, enormous mainland stretches of bundu (arid plains with nearly impenetrable thickets of thorn), the Great Rift Valley where homo sapiens had its beginning, Mount Kilimanjaro, and the lush tropics surrounding that immense inland sea, Lake Victoria.

In the 1890s Britain’s far-flung empire covered a quarter of the globe, including a number of strange, out-of-the -way places. Of all its territories, perhaps none featured more geographical diversity than the vast reaches of British East Africa. This newly-acquired territory, which had been explored by one of the great names in African discovery, encompassed the sultry, clove-laden island of Zanzibar, enormous mainland stretches of bundu (arid plains with nearly impenetrable thickets of thorn), the Great Rift Valley where homo sapiens had its beginning, Mount Kilimanjaro, and the lush tropics surrounding that immense inland sea, Lake Victoria.

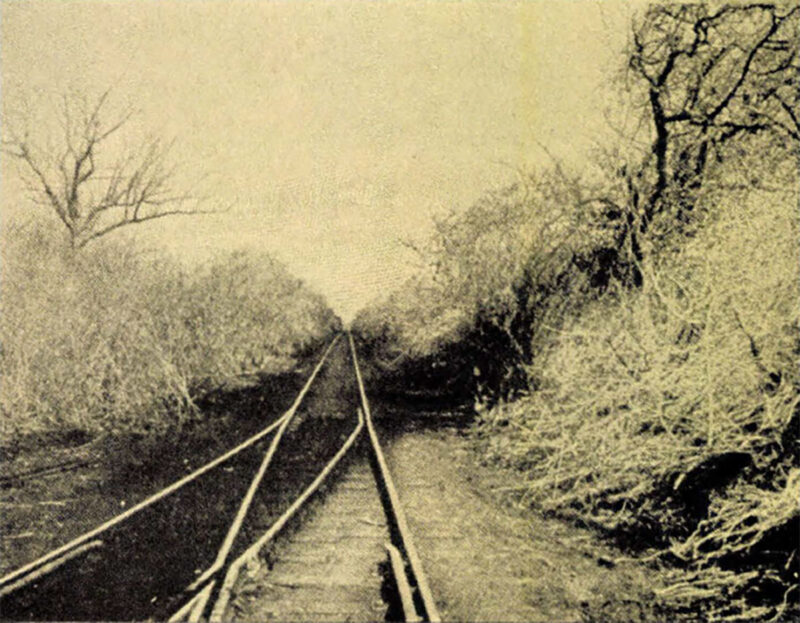

In 1895, a handful of British politicians decided that what the region needed to make it economically viable was a railroad. These astute gentlemen, determined to make a truism of the widely held belief that only “mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun,” moved their colleagues in Parliament to fund construction of the Uganda Railway. Designed to link Africa’s barren east coast with the potentially rich territory around Lake Victoria, it was to become a stupendous engineering challenge.

To many, the enterprise was a hare-brained scheme which gave new meaning to the word boondoggle, but it had cabinet-level backing and support from powerful politicians like Lord George Curzon. Anti-imperialists were outraged and in defeat, their leader, Henry Labouchere, read this bit of scathing doggerel to the bemused House of Commons:

What will it cost no words can express;

What is its object no brain can suppose;

Where it will start from no one can guess;

Where it is going to nobody knows.

What is the use of it none can conjecture;

What it will carry there’s none can define;

And in spite of George Curzon’s superior lecture,

It clearly is naught but a lunatic line.

But not even Labouchere could envision the single greatest disaster which would beset the builders of what author Charles Miller would style as “The Lunatic Express” in his book on the railroad project.

Construction progressed smoothly until the railhead reached the Tsavo River, which the engineer in charge of the Indian work gangs initially viewed as an ideal place for a permanent camp. He could not have been wider of the mark. For it was here, beginning in March of 1898, that the depredations of two huge male lions stopped the railroad for the better part of a year.

The gruesome exploits of the maneaters, together with those of Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson, the man who eventually took their measure, form one of the most fantastic tales in the annals of African adventure.

The very name Tsavo had negative connotations — its meaning in the language of the local Kikamba natives was” laughter. ” In 1898 and on into 1899, the appropriateness of the term would become terrifying clear. In truth, the site was notorious among caravan leaders and natives long before the railway reached the river. Many caravan porters deserted at Tsavo. Legend had it that a certain evil spirit would entice the men away at night and after leading them down to the river, whisk them away. The area was also an old killing ground of the dreaded Masai warrior. Indeed, it had an aura of evil about it.

No sooner had the railroad established its camp when these ominous portents became grisly reality. Searchers looking for a missing coolie found only the man’s skull and feet surrounded by a profusion of lion tracks. The specter that would haunt Tsavo for many months had assumed substance. Further investigation uncovered other human skulls and skeletons scattered around the area.

Within days the phantom lions killed again. This time the flesh of a worker’s face had been torn off, leaving the teeth exposed to form a horrible grinning expression. The hideous remains produced instant pandemonium among the coolies. Tsavo had, as the head engineer so pithily put it, become a “death hole.”

It was at this fateful juncture that John Henry Patterson appeared on the scene. The Englishman was a slender, rather domineering individual full of the purposefulness and rectitude so characteristic of Queen Victoria’s imperial servants. A trained engineer with extensive experience in railway construction, he had risen to his rank while in the Indian Army. Patterson was also an accomplished hunter and doubtless looked upon his posting to East Africa as a splendid opportunity to combine sporting pleasure and work.

At first, Patterson gave little more than passing thought to the tales of man-eating lion. He optimistically expected to bridge the Tsavo and lay track on both sides of the river within a few months. All too soon, however, he found himself at center stage of the gripping drama.

In the latter part of March 1898,about two weeks after his arrival, servants awakened Patterson to inform him that one of his personal attendants, a muscular Sikh named Ungat Singh, had been carried bodily from his tent in a lion’s jaw.

In his book, The Man-Eaters of Tsavo, Patterson provides graphic descriptions of the lions’ kills. On this occasion, he came upon a trail marked by darkening spots of congealed blood, an indication that the cats had indulged in “their habit of licking the skin off so as to get at fresh blood.” Following this macabre spoor, he encountered “a dreadful spectacle” — pieces of flesh , crushed bones and the victim’s intact head” with the eyes staring wide open in a startled, horrified look.” Patterson vowed on the spot to “rid the neighbourhood of the foul brutes.” Little did he realize the immensity of his new task.

Patterson began hunting that very night, armed with a single-barreled Holland .303 rifle and a double-barreled 12-gauge shotgun loaded with a slug and buckshot. He took a stand in a thorn tree near the kill site, reasoning that the lion would return to feed on the remains. But after a few hours of waiting, he would learn that the lions’ habits did not lend themselves to human powers of reasoning.

In the depths of the night, distant roars and the shouts of natives told him the cats had taken another coolie. It was a scenario that would be repeated, with minor variations, time and again over the ensuing weeks and months. The felines seemed gifted with almost supernatural foresight, both as to Patterson’s whereabouts and the location of defenseless men.

Sometimes the lions would go for a week or two without an attack; during other periods their violent incursion came night after night. Their sagacity and irregular habits made Patterson’s task difficult, and more than once he confessed to emotions of “impotent disappointment.” Meanwhile, an atmosphere of terror descended on Tsavo. Even when there were no attacks, the lions’ guttural snarls and roars punctuated the darkness.

The coolies devised all sorts of measures to avoid the marauders. They built heavily-fortified thorn barricades, called bomas, kept fires blazing hroughout the night, posted nightwatchmen who banged on empty cans and contrived all sorts of imaginative sleeping arrangements. Before long, the upper branches of every tall tree near the camp site was festooned with crude hammocks. One such tree splintered under its burden, tumbling the men into the midst of the prowling lions. All these expedients ultimately failed. No matter how secure a boma might seem, the lions would inevitably discover a weak link and claim yet another victim.

With unerring accuracy, the killer cats continued to second-guess their human adversaries, taking victim after victim. Even the hospital was not safe. Having forced it to relocate once because of their deadly forays, the lions soon discovered its new location and took another coolie. In this instance, they devoured their victim on the spot, leaving nothing but his skull and a few fingers. As Patterson noted, somewhat bizarrely, on one of these fingers “was a silver ring, and this, with the teeth (a relic much prized by certain caste), was sent to the man’s widow in India.” His action suggest that Patterson was also beginning to experience a bit of the eerie fatalism which plagued his coolies.

With unerring accuracy, the killer cats continued to second-guess their human adversaries, taking victim after victim. Even the hospital was not safe. Having forced it to relocate once because of their deadly forays, the lions soon discovered its new location and took another coolie. In this instance, they devoured their victim on the spot, leaving nothing but his skull and a few fingers. As Patterson noted, somewhat bizarrely, on one of these fingers “was a silver ring, and this, with the teeth (a relic much prized by certain caste), was sent to the man’s widow in India.” His action suggest that Patterson was also beginning to experience a bit of the eerie fatalism which plagued his coolies.

This became especially true following the sordid incident when the maneaters, having taken yet another victim on a particularly dark, moonless night, consumed their prey within earshot of the hunter. “I could plainly hear them crunching the bones, and the sound of their dreadful purring filled the air and rang in my ears for days afterwards.”

With such unwelcome diversions, it is small wonder that camp morale quickly disintegrated. Patterson’s courageous, unstinting attempts to kill the lions helped at first, but as more coolies fell victim, despair gripped everyone. In desperation he took to stalking the lions in their thorny retreats during the day as well as maintaining his nighttime vigil.

Patterson had always been one for maintaining strict discipline, both in a personal sense and among his men. In fact, it says much for his powerful personality that he maintained order as well as he did. Most workers stuck to their tasks of bridge-building and track laying, despite living in a state of siege. However, a few defiant coolies precipitated yet another crisis for the hard-pressed engineer.

Several malingerers, whom Patterson had previously exposed to public ridicule, hatched a plot to murder their taskmaster. Patterson got wind of the conspiracy and marched among the ringleaders unprotected. One of the bolder spirits actually attempted to seize him, but he avoided the attack. Patterson then leaped atop a rock and began to harangue the mob. He dared anyone to lift a hand against him. This mixture of bluster and bravery worked, for he was never again threatened.

The plucky Englishman needed more than raw courage to deal with his animal foes. The man-eaters had now been about their repugnant business for six months and showed no signs of ending their attacks. By September of 1898, they had become international news. In a well-intentioned if misguided attempt to resolve the crisis, Sir George Whitehouse, chief engineer for the Uganda Railway, authorized a reward of 200 rupees (equivalent to perhaps $3,000 today) for the skin of any lion taken within one mile on either side of the railway line.

The substantial reward, together with the promise of great fame for the successful hunter, made Tsavo a boomtown. Wealthy English sportsmen rubbed elbows with opportunistic freebooters, while civil and military officers on leave arrived en masse. It was a circus devoid of comedy. Any lion, be it a cub or a lioness in advanced stages of pregnancy, became fair game. Patterson found the whole mess distasteful and felt hindered by the invasion of overzealous hunters. Meanwhile, the man-eaters, now extraordinarily wise in the ways of men, continued to wreak havoc.

By now, Patterson was becoming desperate. He tried poisoning several donkey carcasses, but the lions scorned the tainted meat. One scheme would have succeeded, however, had Patterson not been plagued by the most rotten luck imaginable.

He ordered the coolies to build a massive trap, which generated considerable kibitzing among some Tsavo residents. The contraption was comprised of adjoining cages separated by steel bars fashioned from discarded lengths of rail. Patterson intended to serve as bait to lure the man-eaters into the adjacent cubicle. The trap also had an ingeniously designed mechanism that would lock in the beasts once they entered. Then, at point blank range, he could shoot the man-eaters. The workers camouflaged the device within a boma, but left a weak spot where the cats could enter.

Once the trap was complete, Patterson endured mosquitoes by night and the ridicule of his fellow Europeans by day. Fatigue eventually forced him to use volunteer coolies as bait, a decision that he would soon regret.

One of the man-eaters entered the cage and the door locked behind it. The panic stricken coolies in the adjacent enclosure emptied their rifles in the direction of the angry lion, but incredibly, every shot missed. One bullet, however, blew the lock off the door, allowing the man-eater to escape unscathed. Small wonder the superstitious workers regarded the beasts as devils!

On December 1, with Patterson nearing total exhaustion, the most crushing of all blows fell. Hundreds of workers converged on his tent and bluntly announced they would no longer remain at Tsavo — that they had come to work for the government, not to become food for either lions or devils. No sooner had they issued their proclamation than a materials train arrived on its return from the railhead en route to Mombasa on the coast.

Hordes of coolies swarmed aboard like so many panicky lemmings, clutching to even the most precarious perches. The startled engineer, overwhelmed by this veritable onslaught of passengers, chugged away before Patterson could resolve matters. Tsavo was, practically speaking, abandoned. Only Patterson and a handful of brave coolies (or unfortunate souls who had missed the train) remained. The man-eaters had stopped a British railroad!

At this point, seemingly when matters could get no worse, Patterson got a break. Ironically, after the tumult and terror which had so long beset Tsavo, the end was almost anticlimactic. Shortly after daybreak on December 9, a Swahili native ran into Patterson’s boma screaming “Simba.” A lion had attacked a man and his donkeys near the river, killing one of the animals. Patterson snatched a gun and rushed out. In his haste, however he had seized a borrowed double-barrel rifle. Nonetheless, he began stalking thelion. Just as the man-eater came into sight, Patterson’s Swahili companion stumbled, spooking the lion into a patch of jungle.

At this moment of extreme frustration, Patterson had an inspired thought. He decided to drive the lion in much the same way he had hunted tigers in India. Summoning some men to serve as beaters, he arranged them in the classic horseshoe pattern. The beaters had barely started walking when Patterson, positioned atop a seven-foot anthill, saw a huge maneless lion. As he carefully drew a bead, the lion spied him and growled savagely. It was a formidable but unmissable target. “I felt that at last I had him absolutely at my mercy…I pulled the trigger, and to my horror heard the dull snap that tells of a misfire.” Before the lion could charge, Patterson fired the other barrel, and heard the dull thud of a hit. The huge beast immediately plunged into a thorn thicket, where Patterson lost its trail.

A lesser man would have called it quits at that point , but night fall found Patterson at a stand overlooking the donkey kill. After several hours, “a deep long-drawn sigh — a sure sign of hunger — came up from the bushes. ” He immediately realized that he, not the dead donkey, was the object of the lion’s attention. As the tension mounted, an owl, mistaking Patterson for a tree, actually brushed against him with it swings. It says much for his steel nerves and presence of mind that he did not fire in blind panic. Suddenly the lion appeared only several feet away. Patterson fired and the brute thrashed about before subsiding with a “series of mighty groans.” One of the devils was no more.

At dawn the next morning, eight men were needed to carry the lion, which measured nine feet eight inches from nose to tail. Other coolies triumphantly carried Patterson alongside. Congratulatory telegrams poured in and the world’s press lauded his accomplishment. For the moment, Patterson was the lion of the hour. He knew, however, that the second maneater remained at large and immediately began attempts to kill it.

One such attempt was tethering a trio of Iive goats to 250 pounds of steel rail. But the lion simply dragged the goat, weight and all, off into the bush for a leisurely repast. A few nights later, Patterson managed to wound the maneater, and for a time, thought the injury might prove fatal. Then, two days after Christmas, 1898, the killer reappeared, scaring a tree-full of coolies witless in an all-night siege.

Dusk the following evening found Patter on in the same tree. After several uneventful hours, he dozed off despite his best intentions to remain vigilant. He awoke with a start and an “uncanny feeling that something was wrong.” A shadowy movement confirmed his instinct. It was “a most fascinating sight to watch this great brute stealing stealthily round us, taking advantage of every bit of cover as he came. His skill showed that he was an old hand at the terrible game of man-eating.” Patterson fired his trusted Holland four times, scoring two hits before his quarry slipped into the bundu.

At daybreak, accompanied by a gun bearer, he began tracking the lion. The pair came upon the badly-wounded beast within a few hundred yards. As it charged, the hunter drove home yet another .303 slug. Still the lion came on. Patterson quickly turned to his gunbearer for his back-up carbine, only to see the native scrambling up a tree with the gun in tow. He had no choice but to join his gunbearer, and had it not been for the lion’s broken hind leg, he would have never reached safety.

From the security of his perch, Patterson reloaded and fired again, dropping the man-eater. In his jubilation, he “rather foolishly,” as he later admitted, leaped to the ground. The dying feline mustered strength for yet another charge, requiring two more shots before it fell barely five yards away.

The reign of terror was finally over. Now an ancient Kikuyu prophecy which proclaimed that “an iron snake will cross from the lake of salt to the lands of the Great Lake” could be fulfilled. Every mile of this “iron snake” cost £9,500 — a fortune at the time. But the monetary expenses paled in comparison with the human and emotional prices exacted by the maneaters. The deadly lions had killed 38 coolies and an estimated 100 Africans.

The reign of terror was finally over. Now an ancient Kikuyu prophecy which proclaimed that “an iron snake will cross from the lake of salt to the lands of the Great Lake” could be fulfilled. Every mile of this “iron snake” cost £9,500 — a fortune at the time. But the monetary expenses paled in comparison with the human and emotional prices exacted by the maneaters. The deadly lions had killed 38 coolies and an estimated 100 Africans.

In the The Lunatic Express, the best book on the railway project, Charles Miller writes: “…for a while (the lions) actually succeeded (in) gaining a notoriety customarily reserved for the dragons of medieval legend.” If such was the case, Patterson emerged from the epic struggle as a modern-day St. George.

In the heroic engineer’s eyes, however, completing his assigned goal was more significant than killing the man-eaters. With the work force back at full strength, Patterson and the Indian coolies bridged the Tsavo River by early February of 1899. His task was at an end. He had, with the stiff upper lip approach so admired by Victorians, “muddled through.”

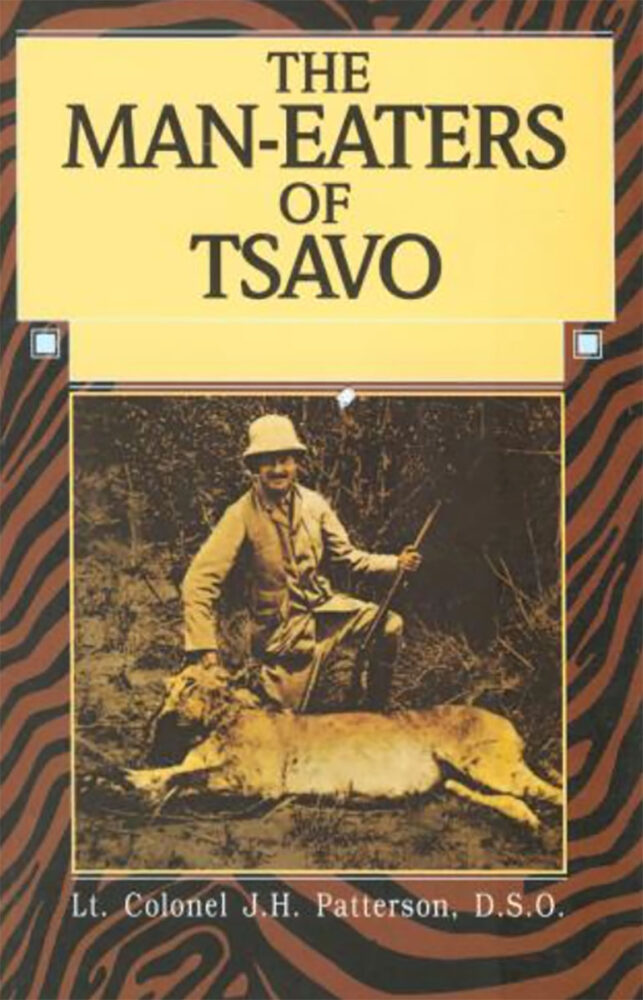

By way of a postscript, some mention should be made of Patterson’s rather checkered subsequent career. The Man Eaters of Tsavo, which did not appear until October 1907, was a best seller. Replete with an introduction by the famous African hunter, Frederick Selou, the book went through numerous editions and earned its author sizeable royalties. The feats it described also helped Patterson gamer the job of Principal Game Ranger for the East African Protectorate (today’s Kenya), a position he took after a stint in the Boer War and extensive travels. It was during his years as a game ranger that he produced another important sporting work, In the Grip of Nyika (1909 — nyika means wilderness).

Ironically, Patterson’s second tenure in East Africa also aroused controversy, although much of it was suppressed or took place behind the scenes. While on a hunting safari with a couple identified only as Mr. and Mrs. B., what Patterson calls “a grave revolver accident” claimed Mr. B. ‘s life. As Colonial Office papers reveal, however, many Englishmen living in the region thought the “accident” was actually murder growing out of a love triangle. Interestingly, official ordered Patterson home on “sick leave” as soon as he and Mrs. B. returned to Nairobi. The full truth likely will never be known.

Whatever might have transpired, Patterson weathered the controversy and later served in World War 1. He became a staunch supporter of the Zionist cause and devoted most of his long life (he survived until 1947) to Jewish concerns. He championed a Jewish state in Palstine and wrote several books including With the Zionists in Gallipoli (1916), With the Judeans in the Palestine Campaign (1922), and American Friends of a Jewish Palestine (1941).

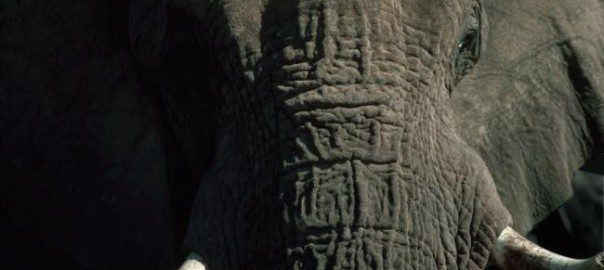

His accomplishments notwithstanding, Patterson did not even merit an obituary in The Times of London. His man-eating adversaries, for their part, have fared rather well at the hands of posterity. Their hides, while certainly not particularly attractive as trophies after years of exposure to the thorny bundu, were carefully preserved and remain the property of Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History. Likewise, thanks to Patterson’s splendid book and other accounts, they have achieved a sort of lasting if perverse fame.

In 1898 John H. Patterson arrived in East Africa with a mission to build a railway bridge over the Tsavo River. Over the course of several weeks Patterson and his mostly Indian workforce were systematically hunted by two man-eating lions. In all, 100 workers were killed, and the entire bridge-building project was delayed.

In 1898 John H. Patterson arrived in East Africa with a mission to build a railway bridge over the Tsavo River. Over the course of several weeks Patterson and his mostly Indian workforce were systematically hunted by two man-eating lions. In all, 100 workers were killed, and the entire bridge-building project was delayed.

As well as being stalked by lions, Patterson had to guard his back against his own increasingly hostile and mutinous workers as he set out to track and kill the man-eaters. Patterson’s account of the lions’ reign of terror and his own attempts to kill them is the stuff of great adventure. Buy Now