Africa’s mystique and appeal often involves danger that, to a large extent, is why hunters the world over are drawn there to hunt big game. Hunting as a resident of Kenya back in the late 1960s, and later while guiding hunting clients in Botswana and Tanzania during the ’70s through the early 2000s, I experienced my share of close calls with Africa’s dangerous game. One of the closest ones happened in Kenya back in 1970.

Five of us—two trackers, two friends from Mombasa, and myself—were on foot following the tracks of three bull elephants through a thorny mass of acacia bush. Leading the way was Bashora, an experienced Waliangulu tracker. I followed Bashora, and behind me were my two friends and Barissa, who was also an excellent tracker and experienced elephant hunter.

The dishpan-size tracks led us down a narrow, well-defined game trail that sliced through a thick patch of bush in hunting block 28 near the eastern boundary of Kenya’s Tsavo West National Park. Recent rains had caused the acacia and comiphora woodland that blanketed the area to explode in fresh green leaf. The tender new growth had drawn the megafauna to the area like a magnet. I happened to have an elephant license and a seven-day Controlled Area Permit (CAP) for block 28 that coincided with the elephant’s exodus out of Tsavo West Park and into the hunting area.

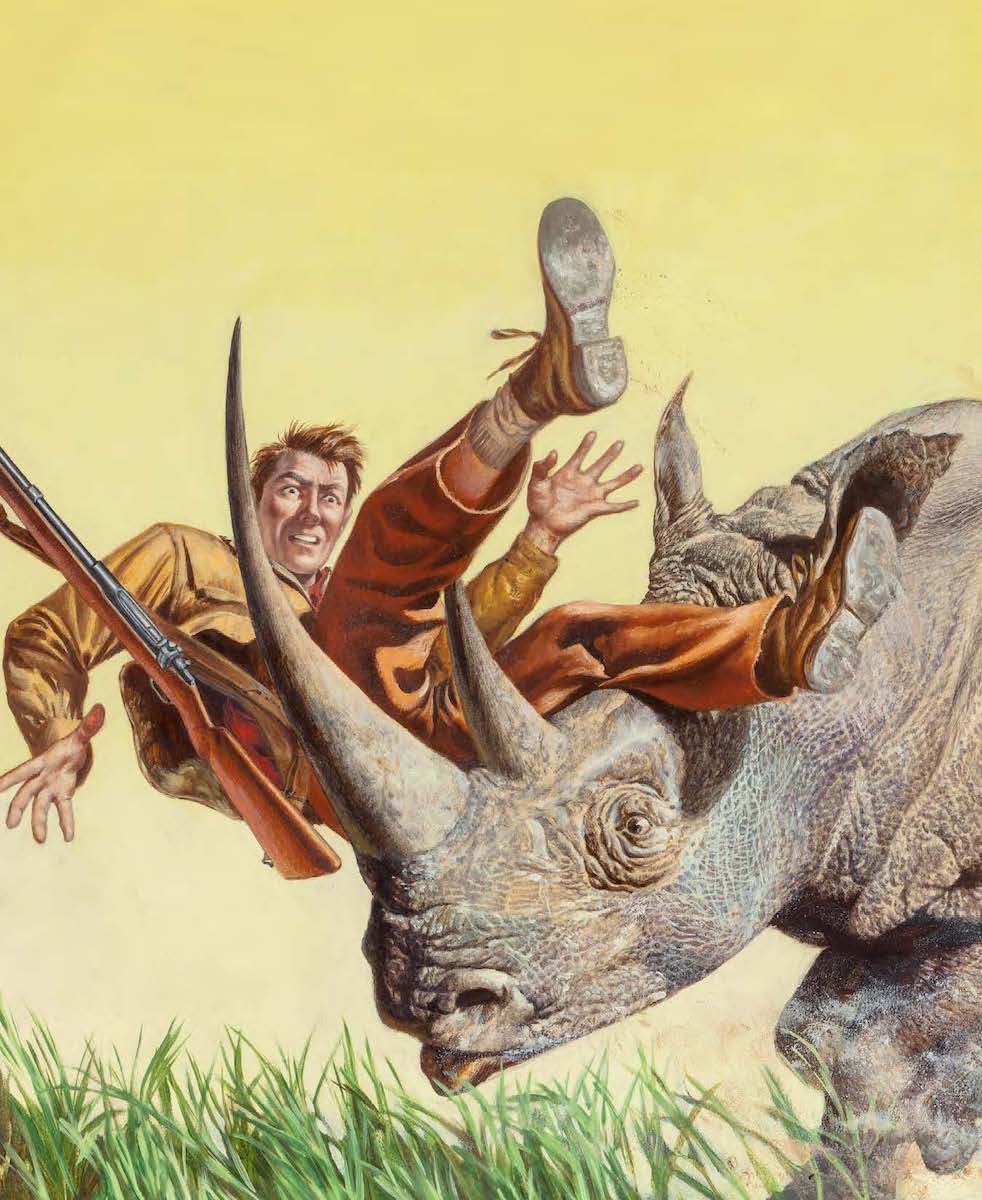

“Somehow we had all managed to cast ourselves clear of what seemed like a runaway freight train . . .We could still hear the rhino blowing and snorting in the distance as we shakily extracted ourselves from the clutch of thorns. Except for a few cuts and scratches caused by impaling ourselves . . . we were all in one piece.”

When I heard the sound, it made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. The distinctive snort came from immediately behind us and was much too close.

Bashora whipped around for a quick look. He was a couple of steps ahead of me, and when I saw his eyes grow wide, he literally threw himself into a thick thorn tangle to our right.

I didn’t need to see what he saw to know I should follow suit, and I immediately flung myself as far from the game trail as I could into the bush. As I landed, a rhino charged past us barely a rifle barrel’s length away, pounding down the path where we’d been walking.

I shouldered my rifle, a Winchester Model 70 chambered in .458 Winchester Magnum and loaded with 500-grain solids, and prepared to shoot if the rhino so much as hesitated or acted like he’d turn and have another go at us. Fortunately for us—and for the belligerent brute—he kept going, busting through thick brush that quickly swallowed him from view. Thundering hooves and breaking branches seemed to echo into the distance.

Somehow, we had all managed to cast ourselves clear of what seemed like a runaway freight train careening through our midst. We could still hear the rhino blowing and snorting in the distance as we shakily extracted ourselves from the clutch of thorns. Except for a few cuts and scratches caused by impaling ourselves on nearly impenetrable thorn bush, we were all in one piece.

By following the rhino’s tracks backward, we reconstructed the dramatic encounter—we’d walked past the old boy as he slumbered peacefully under a shady bush not more than a few yards from the game trail. It must have caused him to awaken suddenly when he caught a whiff of our scent, and his headlong rush may have been a matter of his trying to escape the repugnant human smell rather than that of a determined charge. Even so, it would have been of slight consolation to any of us who might have been skewered on his front horn during his ensuing and rapid pass right through the middle of where we’d been walking.

Thankfully, the bull warned us with a snort as he tried to blow the offensive scent from his nostrils. That incident was certainly one of my closest calls, and it involved an animal I wasn’t even hunting at the time.

Our hunting area was legendary big game country located less than 100 miles inland from Mombasa—country that happened to be prime habitat for the Big Five. It also supported a large variety of plains game, including impala, Grant’s gazelle, eland, lesser kudu, gerenuk, fringe-eared oryx and waterbuck.

Through the 1960s and for much of the ’70s, the country surrounding Tsavo National Park, Africa’s largest game reserve, was thick with black rhino and home to some of Africa’s biggest tuskers, as well as vast herds of Cape buffalo. Predators such as lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas and wild dogs were also plentiful and kept the numerous prey species on constant lookout.

This was truly big game country at its finest . . . and most unforgiving. Make a mistake in judgment, misinterpret an animal’s intentions, or simply underestimate the dangers of walking through the bush, and you might pay for it with your life.

Black rhinos were still so common in the areas we hunted that they were of constant concern anytime we were on foot. Although we regarded them as a nuisance, if someone had told me back then that within the next 20 years black rhinos would be so heavily poached they would cease to exist there, I would have been shocked—and saddened.

The Black & White of Rhinos

The black rhinoceros, or hook-lipped rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), is native to eastern and southern Africa, including Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The other African rhino is the larger white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). The word “white” in the name is often said to be a misinterpretation of the Afrikaans word wyd (Dutch for wijd, meaning “wide”), referring to its square upper lip. The black rhinoceros has a prehensile pointed or hooked lip.

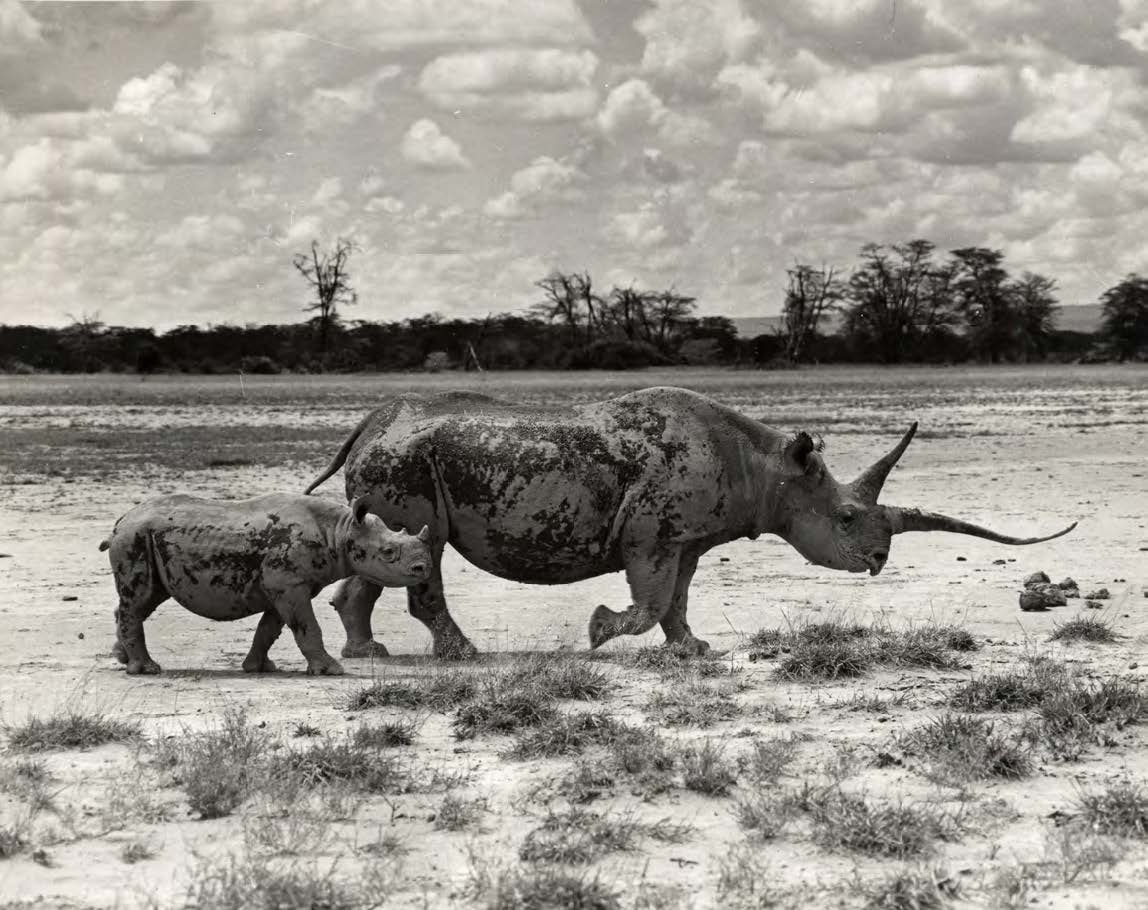

Gertie, a black rhino cow, lived in Kenya’s Amboseli National Park in the mid-1950s. Her front horn, reputed to be the longest of any known living black rhino, was such a curiosity that she and her calf became major attractions to visitors at the park.

With his “wide” mouth, the white rhino is adapted to grazing on the plains and tends to be mostly even tempered, if not placid, whereas the black rhino is a browser and keeps to thicker bush, often displaying downright belligerence and aggression toward anything that disturbs him. Both black and white rhinos have the same body color, which is largely influenced by frequent mud baths, and can vary from brown to gray to red depending on the color of the soil.

In the early part of the 20th century, black rhino numbers were estimated at more than 100,000. They were so numerous that the European settlers arriving in Africa to colonize and establish farms and plantations found them to be a problem and often shot them on sight. But even with indiscriminate killing, and in some cases government culling programs intended to eliminate them from certain areas of agricultural interest, there always seemed to be plenty of rhinos around.

The black rhino’s very nature has contributed largely to his vulnerability to poaching. Their poor eyesight makes them easy to approach, and they are not particularly difficult to kill compared to the tenacious and tough Cape buffalo. When a rhino becomes aware of the close proximity of an unidentified object, they often stand and snort as they try to identify it, using mostly their sense of smell and hearing, relying little on their poor eyesight. A black rhino’s tendency is to charge what they can’t identify, and they often charge even what they can identify it. Back in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, many a safari vehicle wore the signs of altercations with black rhinos, evidenced by the scrapes, dents and holes in the vehicle’s bodywork.

Today, the black rhino population is estimated between only 5,000 and 5,400 animals, which is actually up from a low point of 2,048 individuals 20 years ago. Black rhinos are still considered to be “critically endangered,” with a black market value of more than $30,000 per pound in 2012. This means they are facing an extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild.

The white rhino was nearly wiped out in the early part of the 20th century, but now thrives in sanctuaries in South Africa through intensive game-management projects. There are two subspecies of white rhino: the southern white rhinoceros and the northern white rhinoceros. The northern white rhino is believed to be extinct in the wild.

Ironically, during the 20 years in the ’70s and ’80s that it took to decimate the black rhino populations in East Africa, the southern white rhino numbers enjoyed a rebound under strict and effective management programs in South Africa. By late 2007 there were an estimated 17,460 southern white rhinos in the wild, making them by far the most abundant subspecies of rhino in the world; the number of southern white rhinos outnumbers all other rhino subspecies combined. South Africa is the stronghold for this subspecies, with 93 percent of the world’s white rhinos found there.

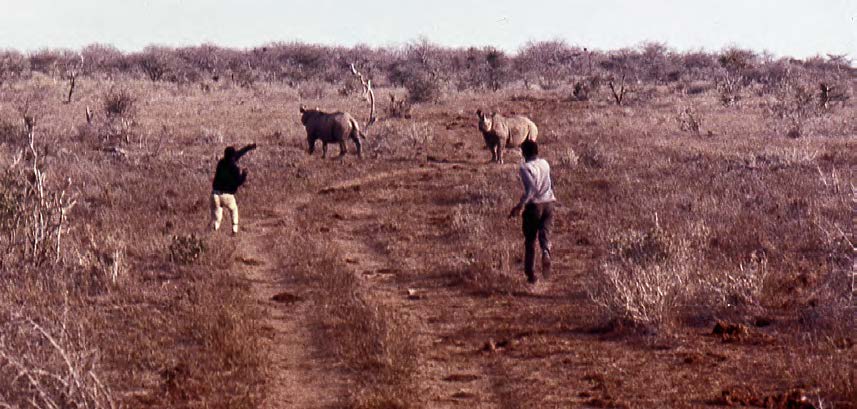

Coogan’s trackers mouth-called these black rhinos, then teased the animals by tossing dirt clods at them.

Today, in spite of continuing poaching pressure, white rhino numbers are increasing in southern Africa. Although white rhinos are currently listed on Appendix I and II of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES), the population of white rhinos in South Africa and Swaziland are stable enough to support limited hunting and international trade as long as the animals go to appropriate and acceptable destinations. Several white rhinos from South Africa have even been relocated to game parks and reserves in Botswana, Namibia, Uganda, Swaziland and Zimbabwe. They have also been introduced outside the former range of the species in Kenya and Zambia, and a small population survives in Mozambique.

It’s all about the Horns

So why are rhinos so relentlessly pursued and slaughtered by poachers? It’s all about their horns—a long one in front and a short one behind it. The horns of most animals have a bony core covered by a thin sheath of keratin, the same substance as hair and fingernails. Rhino horns are unique, however, in that they are composed entirely of keratin. The horns most closely resemble the structure of horse hoofs, turtle beaks and cockatoo bills. Ironically, the rhino’s horn, designed and intended for defense and protection, has become the source and reason for their demise.

Historically, the demand for rhino horn stemmed from the unwavering belief by the Chinese in its mystical and medicinal powers. The Chinese attribute its medicinal powers to curing everything from hangovers to headaches, as well as reducing fevers, treating impotence and even healing venereal diseases.

Back in 1970 when gold was selling for $35 per ounce, powdered rhino horn was being traded in Asia for $90 or more an ounce. Between 1970 and 1992, fully 96 percent of Africa’s remaining black rhinos were killed. A wave of poaching for rhino horn rippled through Kenya and Tanzania, continued south through Zambia’s Luangwa Valley as far the Zambezi River, and spread into Zimbabwe. Political instability and wars have greatly hampered rhino conservation work in Africa, most notably in Angola, Rwanda, Somalia and Sudan.

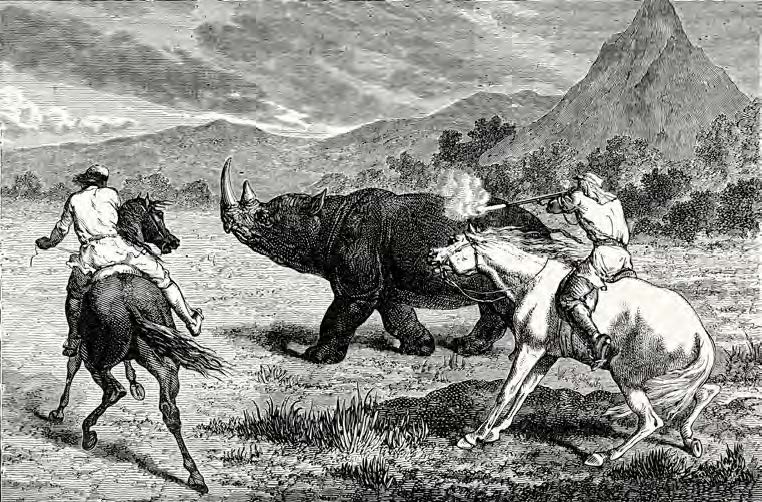

This illustration of a rhino hunt on horseback is from a 19th-century book.

The horns of black rhinos killed in East Africa usually ended up in Yemen, where the material is used to make ornamental handles for jambiyas (daggers), while horn from rhinos poached in southern Africa makes its way to the Far East, where it is used in traditional folk medicine. The trade to Yemen was fueled by the oil boom, when income in the Middle East enabled the rise of a new middle class able to afford luxury items. Although jambiyas can have handles made from a range of substances, such as precious metals, buffalo horn or even plastic, and can be adorned with gemstones, those made of rhino horn are regarded as the “Rolex” version.

Most of the rhino horn being poached today goes to supply the Asian market. The efforts to obtain rhino horn has become so frenzied lately that it has even involved stealing horns from museum mounts, which happened recently in Dublin, Ireland, when a group of masked men roughed up security guards and stole the horns, worth $650,000, off four rhino heads. And that wasn’t the first time: A rhino-head heist spree swept Europe in 2011 as thieves raided museums and auction houses in seven countries, prompting 30 investigations by Europol, 20 of which are still ongoing. Similar robberies have also been on the rise in Africa, as well as in U.S. towns where rhino heads might be displayed in trophy rooms or museums.

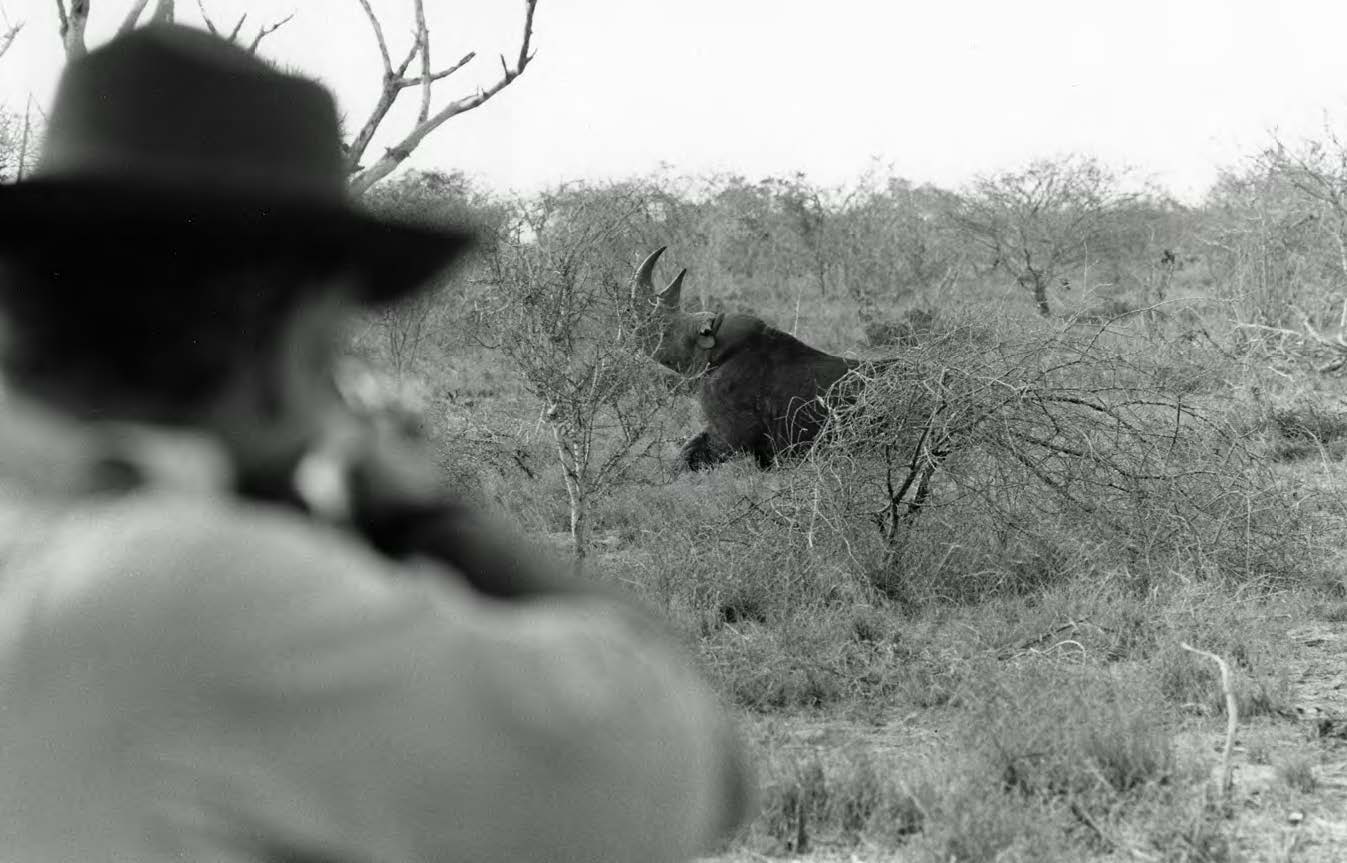

The author was living in Kenya in the ‘90s when he took this photograph of a fellow hunter finishing off a black rhino.

In 2007 rhino horn became even more sought-after when it was reported to have cured a Vietnamese politician of cancer, causing the price and demand to suddenly soar. The odd thing is that the surge in Vietnamese demand is fairly recent. Though rhino horn elixirs for fevers and liver problems were first prescribed in traditional Chinese medicine more than 1,800 years ago, by the early 1990s demand was limited. Trade bans among Asian countries instituted in the 1980s and early 1990s proved largely effective in suppressing supply, with some help from poaching crackdowns in countries where rhinos occur.

Meanwhile the removal of rhino horn powder from traditional Chinese pharmacopeia in the 1990s had largely doused demand. In the early 1990s, for instance, horns sold for only $150-250 per pound, and only around 15 rhinos were poached in South Africa each year from 1990 to 2007. But things started changing in 2008. That year, 83 were killed, followed by 122 the next year. By 2012 that number had hit 688, and in 2014 a total of 1,215 rhinos were poached in South Africa—a 21 percent increase from the previous year. The increase was directly related to a growing demand from some Asian consumers, particularly in Vietnam, for folk remedies containing rhino horn.

Rhino Conservation Projects

A valid question at this point might be, “Is there any hope for the African rhino?” And a valid answer might be, “Maybe.” In addition to the aggressive and dynamic on-the-ground anti-poaching efforts that take place in every country where rhinos still exist, there are also various projects based throughout the former natural range of the black rhino that do offer hope. Rhino-conservation programs have never been more critical than they are today.

As rhinos across Africa fight for survival, Botswana could offer one of their most important refuges. Rhino Conservation Botswana (RCB) is working to increase and protect populations of black and white rhinos with the assistance of not only the Botswana government, but also the English royals, most specifically His Royal Highness Prince Henry of Wales, who has stepped forward to announce that he is a Royal Patron of RCB. He is adding his voice to help raise awareness of the plight of Africa’s black and white rhinos and inspire positive action.

This rhino head and horns were confiscated by game officers in Kenya

Prince Harry visited Botswana in September 2016 to join RCB Director Map Ives in the Okavango Delta on a sensitive operation to fit state-of-the-art electronic tracking devices to critically endangered black rhinos.

“Throughout Africa, rhinos are being poached for their horns at a rate that could make them extinct in the wild within ten years,” Ives explained. “They are completely reliant on our protection and on our efforts to turn the current tide of poaching for their survival. It also gives us great satisfaction to know that what we’re doing is not just important for rhinos, but for the whole of mankind.”

In Kenya, the black rhino population in the Tsavo National Park ecosystem was estimated at 6,000 to 8,000 in the 1970s. By 1989 there were no more than 20 remaining. Of all of Africa’s endangered species, the black rhino is unique because almost 100 percent of its decline can be attributed not to habitat loss or human-wildlife conflict, but to outright poaching. Today’s resurgence in poaching in East Africa has left the black rhino more vulnerable than ever before.

The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust was one of the first organizations to alert the world to the plight of the black rhino in Kenya after two decades of rampant poaching within the country’s established national parks and remote unprotected areas in the north. The Trust provided emergency funding for surveillance and the protection of the few rhinos remaining on private land, and it coordinated joint action by what became known as the “Rhino Action Group,” which was comprised of all concerned conservation organizations within Kenya. Through The Rhino Action Group, the government was spurred into taking urgent measures to retrieve the species from the brink of extinction.

Located in the Tsavo National Park, the Ngulia Rhino Sanctuary was established in 1986 and remains a stronghold for black rhinos as well as a breeding ground to help bolster other rhino sanctuaries and wild populations. In 2007 the sanctuary was expanded from 24 square miles to 35, allowing rhinos more room to roam alongside a multitude of other wildlife, including elephants. The security offered by fenced sanctuaries allows rhinos to live and reproduce without the constant threat of poaching, and it allows researchers to monitor vulnerable black rhino populations.

Zimbabwe PH Peter Garvin examines the horn from a rhino shot with a poisoned dart, but never recovered by the poachers. Even back in 1988 when the incident occurred, the horn would have brought $20,000 on the black market. Chuck Wechsler photo.

In Tanzania, with only three very small and highly vulnerable populations of black rhinos remaining in Ngorongoro Crater Area, Serengeti National Park and the Selous Game Reserve, there was a clear need for the establishment of a new and more secure breeding population in quality habitat within the black rhino’s former range. To meet that need, a successful black rhino project was started in the 1,265-square-mile Mkomazi National Park, which forms the southern extension of the Tsavo ecosystem into northeastern Tanzania. Together with Tsavo National Park in Kenya, Mkomazi forms one of the largest protected areas for wildlife in Africa. The Mkomazi Rhino Sanctuary (MRS) was established in 1991, and an expanded population of black rhinos is now thriving in Mkomazi along with many other animals, including African wild dogs, elephants and lions.

Effective conservation efforts in recent years have seen the steady increase of white rhino numbers, while black rhino numbers inch upward after a long and devastating period of poaching. Even so, black rhinos remain critically endangered, with poaching posing a constant and continuing threat to their survival. The species is currently found in patchy distribution from Kenya down to South Africa. However, almost 98 percent of the total population is found in just four countries: South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Kenya.

The poaching crisis and near extinction of rhinos in Africa can only be reversed through a multifaceted effort involving the continent’s native populations, the various governments, wildlife authorities and the rest of the world. Though rhino projects cannot change the demand for rhino horn, they can provide security that allows the species to breed and increase their numbers. They can also educate and change the attitudes and behaviors of the peoples of Africa, all while creating an awareness of the rhino’s plight so the rest of the world will better understand the urgency of the situation and move to action.

Mike Miller’s first sixty-three African safaris—including trips to Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa and Cameroon—form the basis for Facing the Charge. A gifted storyteller, writer Scott Longman makes Mike’s African stories come alive on these pages, describing in page-turning detail a tremendous range of experiences during which Mike and his colleagues faced charges from the Big Five—Cape buffalo, lion, leopard, elephant and rhino—as well as from man-eating crocodiles, slithering pythons, vengeful baboons, and a hormonal Chevy Tahoe-sized mama hippo who had Mike squarely in her front-view mirror.

Mike Miller’s first sixty-three African safaris—including trips to Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa and Cameroon—form the basis for Facing the Charge. A gifted storyteller, writer Scott Longman makes Mike’s African stories come alive on these pages, describing in page-turning detail a tremendous range of experiences during which Mike and his colleagues faced charges from the Big Five—Cape buffalo, lion, leopard, elephant and rhino—as well as from man-eating crocodiles, slithering pythons, vengeful baboons, and a hormonal Chevy Tahoe-sized mama hippo who had Mike squarely in her front-view mirror.

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria, and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa, and pays tribute to the men and women who have made Africa a second home for Mike. Shop Now