Generally, he would have welcomed the chance to leave the hunter behind and go alone to finish the hunt. It would’ve been a good way to end his bear-hunting career. But this time, he couldn’t.

Kernels of snow splashed from the tracks for several feet in every direction. Where the snow deepened, the bear’s low, swinging belly wedged a path between the dinner-plate sized paw prints.

Kernels of snow splashed from the tracks for several feet in every direction. Where the snow deepened, the bear’s low, swinging belly wedged a path between the dinner-plate sized paw prints.

As Tom steered his snowmobile deeper into the wooded canyon, the tangled willows and scrubby pines engulfed him. Limbs reached out and slashed at his arms as he rode by and sweat burned as it dripped from beneath his fur-lined hat and into his eyes. His head jerked back and forth like a deer edging out into a meadow.

Without stopping his machine, he studied one of the depressions carefully, checking to be sure the five claw marks were still heading in the right direction and the bear had not started backtracking again. The snowshoes tied to the side of his machine caught his eye and he turned away quickly, forcing them out of his mind and fighting the thought of using them . . . which was growing nearer all the time.

The tracks continued farther into the canyon. The snow grew deeper and the trees thicker and then suddenly, the hunters had gone as far as they could. The tangled mass of willows in front of them formed a barrier no machine could penetrate.

Tom peered into the wall for a moment and then down at the tracks which led directly into it. In the middle of one of the foot-deep depressions lay something that held his gaze — a single drop of crimson that stained the whiteness surrounding it. He stared at it until it became blurry. The reality of the moment was becoming obvious.

Tom heard Jim’s snowmobile come up behind his own. He felt Jim’s eyes on his back and could hear his quick breathing.

Jim cleared his throat. “What do we do now?”

Tom didn’t want to look at him. Didn’t want to face him. What he wanted to do was turn around and cuss him out, again. But he knew it was too late for that. Much too late.

It had almost been too easy, Tom thought. They’d kill the last bear and he’d hop the first plane out of Alaska. Head back to Montana and spend the summer fishing the Madison. Get back together with Kathy; maybe put his business degree to use for a while. Settle down.

It had been a good run, he thought. He’d caught some big salmon, climbed a few mountains, hunted with the Eskimos and killed a helluva lot of grizzlies — 14, so far, that spring between he and the other guide, in just 21 days of hunting.

There had been some tough ones, though most of the bears had come pretty easy, he thought. Fresh out of the dens, sitting on winter-killed moose out in the open. But he’d seen enough bears. It was time to go home. Maybe he’d come back in the fall. Guide some caribou and moose hunts. Easy stuff. Or maybe he’d just stay home and hunt ducks and pheasants with his dad. But no more bears. That much he knew.

There had been some tough ones, though most of the bears had come pretty easy, he thought. Fresh out of the dens, sitting on winter-killed moose out in the open. But he’d seen enough bears. It was time to go home. Maybe he’d come back in the fall. Guide some caribou and moose hunts. Easy stuff. Or maybe he’d just stay home and hunt ducks and pheasants with his dad. But no more bears. That much he knew.

Yep, it had been a pretty good run. Until now . . .

“So what do we do?” Jim asked again. His voice cracked in mid-sentence. Tom knew the tone. Panic. Fear. Cowardice. The arrogant edge to it had vanished. A child’s voice had taken its place.

Tom looked down at the snowshoes and then again at the tracks leading into the wall of willows. Finally, he turned to look at Jim.

A stubby grayish-black beard grew around Jim’s cheeks and mouth. Deep weather-lines ran the length of his forehead and on the sides of his eyes. His black hair hung limp and lifeless. His six-foot muscular frame seemed to have shrunk in the last week.

But it was his eyes that said it all. The white had been replaced by bleeding lines of red and they were sunken behind the charcoal bags that hung below them. They seemed to be reaching out to Tom . . . reaching for help.

Tom wondered what the nurses at the hospital would think if they could see Jim now. Or what his fellow doctors who ate lunch with him at the country club overlooking the Houston skyline would say if they could see what their fearless partner had been reduced to.

Tom had seen it with other men. CEOs of billion-dollar corporations, European aristocrats and several doctors. It wasn’t just the bear that did it. It was the cold, barren tundra which spread out like an endless desert of white. The dark, willow- and spruce-infested canyons. The eerie half-light of a night that never really comes. The hundreds of scattered caribou remains you saw every day and the lonely howl of the wolf at night as you laid in your sleeping bag. Reduced a man to just a fraction of himself.

Tom looked at Jim again. So this was the same arrogant, barrel-chested sonofabitch who had told Tom’s boss he’d come to hunt grizzly bears, not change diapers on his baby-faced guide. The same sonofabitch who had killed jaguars in South America, tigers in India, polar bear in Canada and all of the dangerous game in Africa, including a world-record cape buffalo. The same sonofabitch who had, only 24 hours earlier, missed two broadside shots on a grizzly at 25 yards before hitting him solidly . . . in the paunch.

As Tom looked at the dirty blood in the snow. He could still hear the hollow thump just as the bear ambled into the scrubby black spruce.

“I nailed that bastard.”

“I nailed that bastard.”

“You gut-shot him.”

“Right behind the shoulder.”

“About three feet behind.”

“I hit him, didn’t I?”

Tom shook his head, “Yeah, you hit him.”

“Well you finally got a good look at him,” said Jim. “Tell me boy-wonder, you think he’ll make it?”

To hell with the Weatherby he’d promised if they’d killed a big bear, Tom thought. Bastard deserves to have his nose broken.

Jim was not the first difficult hunter Tom had taken out that spring. But each one had been harder than the last. The good hunters came to this desolate, windswept comer of western Alaska for the experience and the opportunity to kill a trophy grizzly bear. Jim had come for a living room decoration. He had paid a premium price for it and he didn’t care how he got it.

Tom took a few deep breaths. “The hit might have angled forward and clipped a lung. Let’s go have a look before it gets too dark.”

“The bastard’s dead. He’s gotta be. Tommy, this .460 Weatherby Magnum is probably the most powerful gun made. I could’ve hit him in the foot and killed him.”

“The bastard’s dead. He’s gotta be. Tommy, this .460 Weatherby Magnum is probably the most powerful gun made. I could’ve hit him in the foot and killed him.”

Tom took another deep breath. “You’re probably right, but put three more shells in and let’s walk up and have a look before it gets too dark.”

Jim shook his head and grabbed three more cigar-sized shells out of his belt. “The bastard’s dead for Christ’s sake. I’ve been hunting since before you were born. I know when I’ve made a good hit.”

Tom heard him but didn’t acknowledge it. He told Jim to walk behind him and off to his right. Tom unshouldered his. 338 and checked the magazine. He slid the bolt forward and put one shell in the barrel.

The slope they were on faced south, and the soft snow was only a foot deep. As they reached the stand of scrubby spruce trees where they had last seen the bear, Tom saw the animal’s tracks and a hole in the trunk of a tree. The first shot. He noticed where the bark had splintered. Two feet low and a foot left of the bear.

He took four more steps and looked down. The smell alerted him before he actually saw the thick, olive-colored smear on the white snow. Tom bent down and rubbed it with his fingers.

“Find him?” Jim asked.

Tom shook his head.

He heard Jim come up behind him and stop walking. Heard him breathing. He waited for a long time for Jim’s smartass remark. But none came. Finally, Tom turned to look at him. For the first time all week the arrogant grin was gone from Jim’s face. He looked puzzled more than anything.

Jim glanced at the snow and then at the deep, wooded canyon below them and then back to the snow.

Tom kept staring into Jim’s eyes. Something was vanishing from them.

Tom kept staring into Jim’s eyes. Something was vanishing from them.

“I gut-shot him, huh.”

Tom looked at the falling sun and then at his watch. It was nearly 11 p.m. The fading light of early May would be gone soon.

“Let’s get the snowmobiles and we’ll set up a shelter and get something to eat. It will be light in another four hours and we’ll get on the track first thing in the morning. Hopefully he’ll lie down and stiffen up. If we push him, he’s liable to keep going until he hits the bottom of the canyon. And in that mess of willows we’d have our hands full trying to get him out.”

Jim ‘s eyes flashed quickly down the canyon into the thick, wooded bottom and then back to the dirty blood.

“I gut-shot him, huh.”

“Yeah you gut-shot him! We’ll find him first thing int he morning.”

They cut the tracks at first light and after an hour found where the bear had holed up for the night, only a few hundred yards from where he’d been shot. A frozen pool of blood lay in the middle of the trampled snow. Tom knelt down and touched the snow. The tracks leading out of the bed were only a few minutes old. The blood had almost completely clotted. There were only scattered pin-drops now.

The bear’s pigeon-toed tracks plodded deeper and deeper into the canyon all afternoon. Tom’s initial hopes that the bear would either stiffen up and die or come out onto the tundra slowly faded as the day went on. The tracks began to meander as they neared the bottom. When they finally went into the wall of tangled willows, Tom knew that it was just a matter of time.

“What do we do now?” Jim asked yet again.

“Well, we’ll have to put on the snowshoes and go in there and pull him out by the tail.” That was what they called it when you had to deal with a wounded bear in the really thick stuff. It was not only the most difficult part of hunting grizzlies, it was also the deadliest. “The way his tracks have been wandering, I doubt he’s gone far.”

“Well, we’ll have to put on the snowshoes and go in there and pull him out by the tail.” That was what they called it when you had to deal with a wounded bear in the really thick stuff. It was not only the most difficult part of hunting grizzlies, it was also the deadliest. “The way his tracks have been wandering, I doubt he’s gone far.”

Tom kept his eyes on the trees in front of him as he waited for Jim’s response. A full minute passed and finally Tom turned to him. Jim’s face gave nothing away. Other than the understandable fear, which showed through his eyes, his expression was featureless.

Tom finally knelt down and began putting on his snowshoes when Jim said plainly, “Tm not going in there.”

“What?”

“I’m not going in there,” he said again. “It’s just a damned bear. I’m not gonna go in there and get myself killed just for some damned bear.”

“Nobody’s gonna get killed.”

“That bear is sitting in there listening to every damned word we’re saying,” said Jim. “I’m a doctor. I’ve got a family. You’re just a kid. You don’t know shit.”

“Listen Jim, all I know is that there is a helluva good bear in there somewhere and he’s got a chunk of lead in his belly and he’s probably not feeling too well. So if you’re not going in there with me, I’m going in myself.”

“Fine. Go. That’s what you get paid for.”

Tom snapped the last buckle on his snowshoe and unshouldered his rifle. Jim was still sitting on his machine. Tom took two steps into the willows and then stopped.

Generally, he would have welcomed the chance to leave the hunter behind and go alone to finish the hunt. He’d done it twice already that season. It would’ve been a good way to end his bear-hunting career. But this time, he couldn’t.

Generally, he would have welcomed the chance to leave the hunter behind and go alone to finish the hunt. He’d done it twice already that season. It would’ve been a good way to end his bear-hunting career. But this time, he couldn’t.

He turned around and faced Jim. They were in a small clearing with just their snowmobiles between them. The arctic sun was hidden by low, gray clouds that cast a dull, flat light on the canyon walls behind them.

“I just want to ask you something,” said Tom. ‘What are you going to do with this bear after I kill him?”

A confused look crossed Jim’s face. ‘What?”

Tom took another step toward him. ‘What are you going to do with the hide of this bear when you get home?”

“Well, I guess I’ll probably put him in my room.”

“Your trophy room, right?”

”That’s right. Why, what the hell do you care what I do with him?”

Tom knew that if his boss heard what he was saying he would be out of a job, but he didn’t care.

“Well tell me then. What are you going to tell your doctor friends and your grandkids when they see this bear in your room and ask you to tell them the story of how you killed it?”

“The story’s not over yet.”

Tom wanted to stop, but couldn’t. He’d already gone too far. “Do you want to look up at that bear on your wall for the rest of your life and be embarrassed by it?

“My boss tells me you killed a charging cape buffalo at 10 paces. He said you held the world record for a few years. Yet in all the stories you’ve told me over the last week, you’ve never mentioned it.

“I’d like to know who really shot that buffalo. You or your guide.”

Jim looked at the ground.

And then Tom said something that surprised even himself.

“Look, Jim, you don’t have to come in there with me. It’s my job and it’s what you’re paying me for. But damnit I want you to come. Not for my sake . . . for the bear’s.

“He’s a helluva good bear. He doesn’t deserve to be put on your wall and looked at with embarrassment or have a lie told about how he died.” Tom paused for a moment. “Just come in there with me . . . I’m not gonna let that bear kill you.”

Jim lifted his eyes from the ground and looked at Tom. Finally, a nervous grin creased his lips. “You promise.”

Tom smiled, “I promise. Now let’s go get your bear.”

Jim shook his head as he reached down and unstrapped the snowshoes from his snowmobile. Tom walked over and helped him put them on.

“Now it’s gonna be thick in there,” Tom said as he buckled the snowshoes, not looking at Jim. “I’ll stay right on his tracks. You stay behind me about five feet and off to the side a little. When he comes, he’s gonna be right on top of us, but down here, the snow is deep so you should have time for at least one or two good shots. I know you’ve heard this before, but if he comes from the side, shoot at the shoulder, not behind it like you would with a whitetail. You need to break him down, not bleed him to death and it usually takes more than one shot to do it. Now, if he comes straight at us, you’ve really only got one choice. It’s just like shooting an elephant, only smaller. So make it count! OK? And oh yeah, remember I’ve got a girlfriend in Montana I wanna get back and see.” Tom laughed and Jim tried to.

“Now it’s gonna be thick in there,” Tom said as he buckled the snowshoes, not looking at Jim. “I’ll stay right on his tracks. You stay behind me about five feet and off to the side a little. When he comes, he’s gonna be right on top of us, but down here, the snow is deep so you should have time for at least one or two good shots. I know you’ve heard this before, but if he comes from the side, shoot at the shoulder, not behind it like you would with a whitetail. You need to break him down, not bleed him to death and it usually takes more than one shot to do it. Now, if he comes straight at us, you’ve really only got one choice. It’s just like shooting an elephant, only smaller. So make it count! OK? And oh yeah, remember I’ve got a girlfriend in Montana I wanna get back and see.” Tom laughed and Jim tried to.

“What if I miss?”

“You won’t.”

“How do you know?”

“You just won’t. You’ve got a wife and family that I know you care about.” Tom shook his head. “You won’t miss.”

When Tom finished putting on Jim’s snowshoes, they stood up and each checked their rifles. Tom looked at Jim and forced a smile.

“You sure you’re ready for this?”

“No.”

“Good. Let’s go.”

As they penetrated the tangled mass of willows, Tom soon realized it was even thicker than he had imagined. The tracks followed no distinct line and it took much of his attention to stay with them. Visibility dropped to just over a rifle’s length and his eyes darted from side to side. He was half-crouched, with the rifle in both hands — every muscle poised to spring. All that he had done in his life and all that he aspired to do, came down to what was about to happen.

The snow crunched loudly beneath the webbed snowshoes. It reminded Tom why he hated the big contraptions. He took one more step and as the crunching snow echoed in his ears, he knew he was crossing that invisible line when it is impossible to tell who is the hunter and who is the hunted. Tom felt himself taking several steps — moving much too fast, but then realized he was taking only one and then stopping, looking and listening. For the twitch of an ear, the snap of a twig, snow falling from a branch. Anything.

The pounding of his heart grew so loud, he turned to see if Jim could hear it. Jim’s blank stare through his blood-stained eyes said it all. He could hear it alright. Tom thought of the misfire Jim had when they had sighted-in his rifle.

At that instant, Tom realized he was doing the wrong thing. He was trying to provoke a gut-shot grizzly into charging a hunter who had told him he didn’t want to go in. Tom stopped and turned back to Jim. He was just about to call the whole thing off and tell Jim to go back to the snowmobiles, when suddenly Jim’s eyes grew wide. The forest of willows in front of them burst open and he saw the massive blur of hate-filled fur rushing toward them and Tom’s heart stopped pounding and his hands quit shaking and in one motion, he shouldered his rifle, tripped the safety and hollered “Shoot!”

Tom centered his rifle between the beady, blood-filled eyes as the grizzly floundered through the deep snow, his jaws popping loudly. For just a moment Tom imagined his client running as fast he could in the opposite direction, when suddenly the blast of Jim’s rifle roared by his head and the big boar went down, staining the snow with red. Over the ringing in his ears he could hear Jim working the bolt on his rifle and just as the bear rose another blast ripped by Tom’s head and the grizzly went down again and before he could say, “Take him again,” a third shot smashed into the bear’s chest.

Tom centered his rifle between the beady, blood-filled eyes as the grizzly floundered through the deep snow, his jaws popping loudly. For just a moment Tom imagined his client running as fast he could in the opposite direction, when suddenly the blast of Jim’s rifle roared by his head and the big boar went down, staining the snow with red. Over the ringing in his ears he could hear Jim working the bolt on his rifle and just as the bear rose another blast ripped by Tom’s head and the grizzly went down again and before he could say, “Take him again,” a third shot smashed into the bear’s chest.

And then it was over. And except for the ringing in his ears, it was quiet for a long time.

They were still less than 50 feet from the machines and Jim had been right; the bear had been close enough to hear every word they had said.

Finally, the silence was broken by a long sigh of relief. It was Tom, breathing again. Alive.

The big boar lay a rifle’s length away from him. Its thick, sandy blond hair glistened from the melting snow. Tom stared at the bear for a long time. And then slowly turned around.

Five feet behind him stood a fifty-two-year-old surgeon from Houston, Texas, clutching his rifle with tears running down his cheeks and a smile on his face.

Tom looked back at the huge animal in front of him and nodded his head slowly. “Helluva good bear,” he whispered.

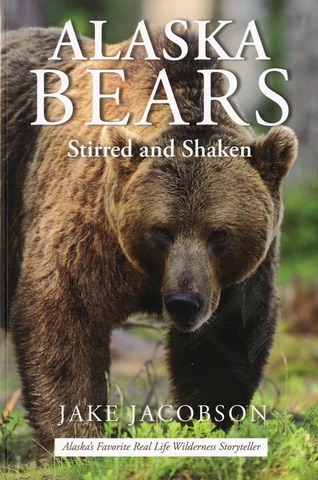

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

Jake came to Alaska in 1967 and among other things, he holds Alaska Master Guide license #54, a commercial Pilot license, a 100Ton Mariner’s license, is a Benefactor Life member of the NRA and has operated from his eighty acre private land located 155 miles north of the Arctic Circle since 1969. Buy Now