Everybody had now gathered but Steve. When questioned, the other drivers disclaimed all knowledge of his whereabouts or his peculiar behavior. But they knew perfectly of both.

For a very long time we have had on the plantation a black man named Steve. For a generation he worked for us; and he is with me to this day. While we usually hade certain workers who could be counted on to accomplish even difficult material tasks, in what might be termed the realm of the psychic, Steve reigned supreme. For some reason, he was at his best when something esoteric and peculiar had to be accomplished. My Colonel early recognized Steve’s strange talent, and occasionally called on him to exercise it.

Thus when the lady in green came to us for a visit, and came with the hope of killing a regal buck, I felt called upon to enlist the darksome strategy of Steve.

“Steve,” I asked, “have you ever seen a woman wear pants?”

“I ain’t done seen it, Cap’n,” he responded, a fervent fire of recollection kindling in his eyes, “but I has done seen some wimmins what act like dey wears dem.”

“Has your Amnesia ever worn them?”

“When I is around home,” he assured me, “she don’t ever wear anything else but.”

“Have you two been falling out again, Steve?”

“Cap’n,” he answered solemnly, “for yeahs and yeahs we ain’t never done fell in.”

“I guess she doesn’t like your playing around with all these young girls, and leaving her at home.”

“I tole her dat woman and cat is to stay home; man and dog is to go abroad. She didn’t like dat atall, atall.”

“Well,” I said, “this is Friday. Monday will be Christmas Day. I know just one way I can get you out of the dog-house where Amnesia has put you. Wouldn’t you like to get out for Christmas?”

“Well,” I said, “this is Friday. Monday will be Christmas Day. I know just one way I can get you out of the dog-house where Amnesia has put you. Wouldn’t you like to get out for Christmas?”

Steve licked his lips, a sure sign that he is about to take the bait. Besides, as I had beforehand been of assistance to him in the vital matter of domestic reconciliations, he regards me as a kind of magician.

“Tomorrow,” I told him, “will be Saturday, the day before Christmas Eve. I will help you, but I expect you to help me.” I was testing his loyalty in a large way.

Haunted by a sense of his own helplessness and by the mastery of his huge Amnesia, he appeared pathetically eager to do anything. Inf act, such was his yielding mood that I had to be careful what I asked him to do, for he would do it. Steve can resist anything but temptation.

”I’m giving a big deer drive tomorrow,” I said. “There will be 20 men and one woman — but I hear she wears pants.”

“Great Gawd,” was Steve’s comment.

“Green ones,” I went on.

“Jeedus!”

“Now, Steve, you know that old flathorn buck in the Wambaw Corner — the one that has been dodging us for about five years?”

“You mean him what hab dem yaller horns, flat same like a paddle?”

“He’s the one.”

“Cap’n, dat’s a buck what I knows like I knows the way to another man’s watermelon patch,” Steve assured me grinning.

“What you want me to do? And how Amnesia suddenly gwine take me back because of what you is planning for me to do?”

“Well,” I told him, “you’ve got a job, all right. I don’t want to be unfair to these men, but ordinary bucks will do very well for them. Your business is to get the buck with the palmated horns to run to the lady in green. If you will do this, I will give you a whole haunch of venison, a ham out of my smoke-house, a dollar in cash and a dress for Amnesia. How about it?”

Steve was stunned. When he came to, he said, “Boss, when I gits to heaben, I ain’t gwine ask, ‘How ’boutit?'”

“Of course,” I told him, “I will put her on the Crippled Oak Stand. You know that is the favorite buck run. Just how you are going to get him to run there I don’t know, but you probably can figure it out. Oh,” I added, “I will not hold you responsible for her killing the buck. Being a woman, she’ll probably miss it anyway. But I want you to give her a chance to shoot.”

I could see that Steve was already deep in his problem. Knowing the woods like an Indian, so familiar with game that he can almost talk with it, familiar also with the likelihood of big game’s acting in ways unpredictable, Steve was pretty well equipped for his task. I could almost see how he would enjoy this particular job.

“One more thing,” I told him: “this lady doesn’t shoot a shotgun. She always uses a rifle.”

“Cap’n,” he sensibly asked, “does you think she knows a deer? If she don’t, I mustn’t get too close to dat rifle.”

“I have never seen her,” I told him, “and I don’t know whether she is a real huntress. All I know about her is what I have been told. But she’s the daughter of one of my best friends, a gentleman from Philadelphia. I want her to have a good time. Think of what it would mean if she could kill the crowned king of Wambaw Corner!”

“I sure loves to please wimmins,” Steve mused, “But so far I ain’t done had too much of luck.”

As we parted I kept pounding home his job to him: “Drive the buck with the flat horns to the Crippled Oak Stand. Drive him there if you have to head him off. And remember the haunch and the ham that will be yours if you manage it right.”

Not long after daylight the following morning the crowds of Christmas hunters assembled in my plantation yard. As the season was nearing its close, every man I had invited came. And there was the lady in green. When I saw her, I was ashamed of the way in which I had bandied words with Steve about the nature of her attire. She was slender, graceful and very lovely. She looked like Maid Marian. Clad in Lincoln green, with a jaunty feather in her Robin Hood’s cap, she was the attraction of all eyes. I could see that all the men were in love with her, and I didn’t feel any too emotionally normal myself. There was nothing about her of the type of huntress I had described to Steve. She appeared a strange combination of an elf, a child and a woman; and though I do not profess to know much about such matters, that particular combination seems especially alluring, perhaps dangerously so.

While my drivers were getting their horses ready, and while stately deer hounds, woolly dogs and curs of low degree gathered from far and near on account of the general air of festivity and the promise of some break in the general hunger situation, I got everybody together and told them that we planned to drive the great Wambaw Corner; that we had standers enough to take care of the whole place, we had drivers and dogs, we had deer. The great, and really the only, question was, can anybody hit anything? That is often a pertinent question in hunting.

Wambaw Corner is peculiarly situated. A tract of nearly a thousand acres, it is bounded on two sides by the wide and deep Wambaw Creek. On one side is the famous Lucas Reserve, an immense backwater, formerly used for waterpower, but now chiefly for bass and bream. In shape this place is a long and comparatively narrow peninsula, with water on three sides. On the south runs a wide road, along which I usually post my standers; but when I have enough (or too many), I post them along the creek. The chance there is excellent, for if a buck is suspicious there’s nothing he’ll do quicker than dodge back and swim the creek.

With the woods still sparkling with dew, and fragrant with the aromas from myrtles and pines, I posted all my standers. I had sent my drivers far down on the tip of the peninsula, to drive it out to the road. I had also had a last word with Steve.

“Only one mistake you might be can is makin’, Cap’n,” he told me. “I dunno how ’bout wid a gun, but with a rollin’-pin or a skillet or a hatchet a woman don’t eber seem to miss. Anyhow,” he particularized, “dey don’t neber miss me!”

“Have you got your plan made?” I asked him. “You’ve got five other boys to drive. That just about sets you free to do what you want to.”

“I got my plan,” he said. “And,” he added darkly, “if so happen it be dat I don’t come out with de other drivers, you will onnerstand.”

In a place like Wambaw Creek there are at times a great many deer. They love its remote quiet, its pine hills, its abundant food, its watery edges. I have seen as many as six fine bucks run out of there on a single drive, a flock of wild turkeys, and heaven knows how many does. I have likewise seen wild boars emerge from that wilderness — huge hulking brutes, built like oversize hyenas, and they are ugly customers to handle.

I knew that there was sure to be a good deal of shooting on this drive, certain to be some missing and possibly to be some killing. Everybody seemed keyed just right for the sport. I had men with me who had hunted all over the world, grizzled backwoods men who had never hunted more than 20 miles from their homes, pure amateurs, some insatiable hunters but rotten shots — and I had the lady in green.

After I had posted the men, there being no stand for me, or perhaps for a more romantic reason, I decided to stand with Maid Marian. She seemed like such a child to shoot down a big buck; yet she was jaunty and serene. When I had explained to certain of the standers as I posted them just how an old stag would come up to them, I could see, from the way they began to sweat and blink, that they were in the incipient stages of nervous breakdowns. But not so my Sherwood Forest girl.

Her stand, by the famous Crippled Oak, was on a high bank in the pinelands. Before her and behind her was a dense cypress swamp, in the dark fastness of which it was almost impossible to get a shot at a deer. If the buck came, she would have to shoot him when he broke across the bank, and likely on the full run — climbing it, soaring across it, or launching himself down the farther bank. All this I carefully explained to her. She listened intently and intelligently.

She appeared concerned over my concern. “You need not worry,” she assured, for my comfort. “If he comes, I will kill him.”

“Have you killed deer before?” I asked.

“No,” she admitted lightly but undaunted. “I never even saw one.”

My heart failed me. “This one,” I told her, hoping that Steve’s maneuvering would be effective, “is likely to have big yellow horns. He’s an old wildwood hero. I hope you get him.”

About that time I heard the drivers put in, and I mean they did. A Christmas hunt on a Carolina plantation brings out everything a black worker has in the way of vocal eminence. Far back near the river they whooped and shouted, yelled and sang. Then I heard the hounds begin to tune up.

Maid Marian was listening, with her little head pertly tipped to one side.

“What is all that noise?” she asked with devastating imbecility.

Tediously I explained that the deer were lying down, that our workers and the dogs roused them, and that by good fortune an old rough-shod stag might come our way.

“I understand,” she nodded brightly. But I was sure she didn’t.

Another thing disconcerted me: I could hear the voice of Prince, of Sam’l, of Will and of Precinct; Evergreen’s voice was loud on the still air. But not once did I hear the hound dog whoop of Steve. However, his silence did indicate that he was about some mysterious business.

In a few minutes a perfect bedlam in one of the deep corners showed that a stag had been roused. The wild clamor headed northward, toward the creek and soon I heard a gun blare twice. But the pack did not stop. There was a swift veering southward. Before long I heard shots from that direction, but whoever tried must have failed.

The pack headed northeast, toward the road on which we were standing, but far from us. I somehow felt, from his wily maneuvers, that this was the buck with the palmated horns. Ordinary bucks would do no such dodging, and the fact that he had been twice missed would indicate that the standers had seen something very disconcerting.

Watching the lady in green for any tell-tale sign of a break in nerves, I could discover none. She just seemed to be taking a childish delight in all the excitement. She was enjoying it without getting excited herself.

About that time, I heard the stander at the far eastern end of the road shoot; a minute later he shot again. He was a good man, a deliberate shot. Perhaps he had done what I wanted Maid Marian to do. But no. The pack now turned toward us.

Judging from the speed of the hounds, there was nothing the matter with the deer; judging by their direction, they were running parallel to the road, at a little over a hundred yards from it. It was a favorite buck run, and at any moment he might flare across the road to one of the standers at the critical crossings. Ours was the last stand on the extreme west. It seemed very unlikely that he would pass all those crossings and come to us. Now the hounds were running closer to the road. It sounded as if the buck were about to cross.

It is now just 50 years since I shot my first buck, and I have hunted deer every year since that initial adventure. But never in all my experience as a deer hunter have I heard what I then heard on that road, on which I had 12 standers. Judging from the shots, the buck must have come within easy sight, if not within range, of every stander. The bombardment was continuous. Together with the shots, as the circus came nearer, I could hear wild and angry shouts; I thought I heard some heavy profanity, and I hoped the lady in green missed this.

She was leaning against the Crippled Oak, cool as a frosted apple. I was behind the tree, pretty nervous for her sake.

“Look out, now,” I whispered. “He may cross here at any minute.”

My eyes kept searching for the buck to break cover. Suddenly, directly in front of the stander next to us, I saw what I took to be the flash of a whitetail. The stander fired both barrels. Then I saw him dash his hat to the ground and jump on it in a kind of frenzy that hardly indicated joy and triumph.

The next thing I knew, the little rifle of the lady in green was up. I did not even see the deer. The rifle spoke. The clamoring pack, now almost upon us, began a wild milling. Then they hushed.

“All right,” said Maid Marian serenely, “I killed him.”

Gentlemen, she spoke the truth, and the stag she killed was the buck with the palmated horns. At 60 yards, in a full run, he had been drilled through the heart. On several occasions I had seen his horns, but I had not dreamed that they were so fine — perfect, 10-point, golden in color, with the palmation of a full two inches. A massive and beautiful trophy they were, of a kind that many a good sportsman spends a lifetime seeking, and often spends it in vain.

However, mingled with my pride and satisfaction there was a certain sense of guilt; yet I was trying to justify myself with the noble old sentiment, “Women and children first.” I had told Steve to drive this buck to my lady in green. He had done it — heaven knows how. He would tell me later. But his plan had worked. But now came the critical phase of the whole proceeding. Standers and drivers began to gather, and afar off I could hear many deep oaths. These, I felt sure, would subside in the presence of Maid Marian. They did, but not the anger and the protests.

There seemed to be one general question, asked in such a way that it would be well for the person referred to to keep his distance. “Where’s that driver?” I heard on all sides. “I mean the big, black, slue-footed driver. I believe you call him Steve. I had a good mind to shoot him.”

There seemed to be one general question, asked in such a way that it would be well for the person referred to to keep his distance. “Where’s that driver?” I heard on all sides. “I mean the big, black, slue-footed driver. I believe you call him Steve. I had a good mind to shoot him.”

“I’d have killed that buck if he hadn’t got in the way.”‘

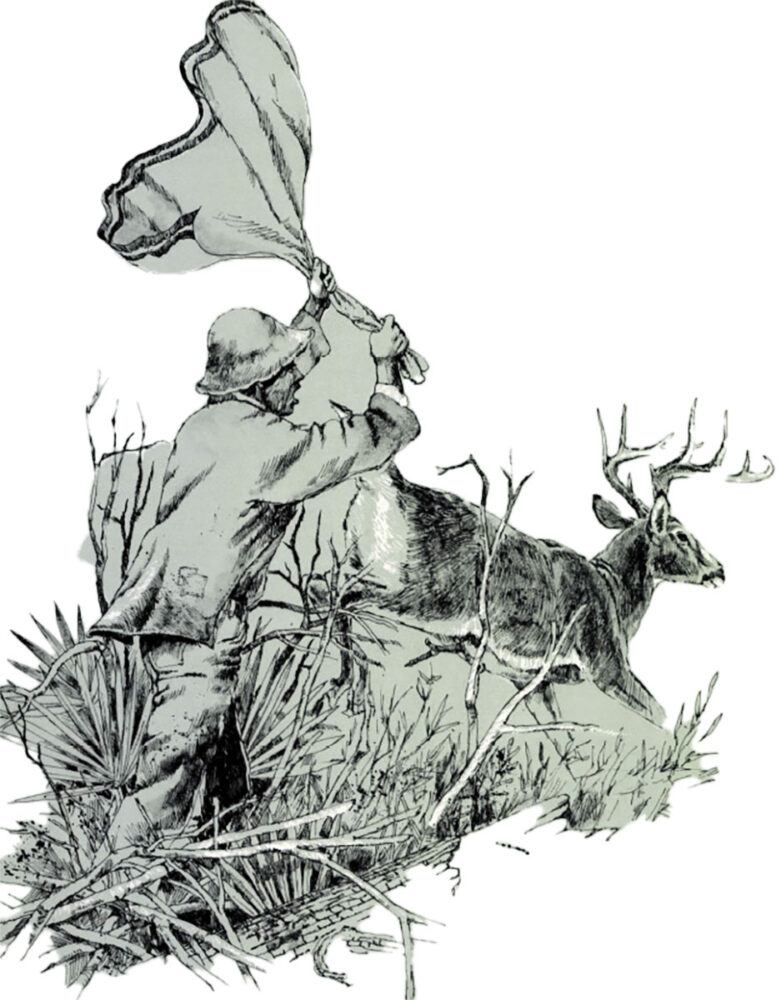

”What was that flag he was waving? Looked to me like he was trying to turn the buck from us.”

“He was coming right on me when he jumped out of a bush and started waving that flag.”

“Well, after all, gentlemen,” I said, “here’s the buck, and I must say the lady made a grand shot. Wouldn’t you rather have her kill him than do so yourselves?”

Everybody had now gathered but Steve. When questioned, the other drivers disclaimed all knowledge of his whereabouts or his peculiar behavior. But they knew perfectly of both. One artfully sidetracked the whole painful discussion by saying, “Steve ain’t neber been no good deer driver nohow.”

Tyler Somerset, a prince of a backwoodsmen, drew me aside. “Say,” he said, “I know what went on back there. You can’t fool me. That’s the smartest deer driver I ever did see. More than once he outran that buck. And he sure can dodge buckshot. I wonder where he got that red and white flag he used to turn that old buck?”

We made several other drives that day. Five more stags were slain. But the buck and the shot of the lady in green remained the records. On those later drives Steve put in no appearance.

When my friends were safely gone, Steve shambled out of hiding to claim his just reward. I loaded him down with Christmas.

“By the way,” I said, “some of the standers told me that you headed that buck with a red and white flag. Where did you get that?”

Steve grinned with massive shyness, as he does only when anything feminine comes to his mind. “Dat’s de biggest chance I took — wusser dan dodging buckshot. Dat was Amnesia’s Sunday petticoat.”

“Huh,” I muttered with gloomy foreboding. “If she ever finds that one out, I’ll have to take you to the hospital.”

“Cap’n, I done arrange it,” he told me — the old schemer! “I did tore seven holes in it with all that wavin’; but I tole Amnesia I was ashamed to have my gal wear a raggety petticoat, and you was gwine give me a dollar, and I was gwine give it to her to buy a new one for Christmas.”

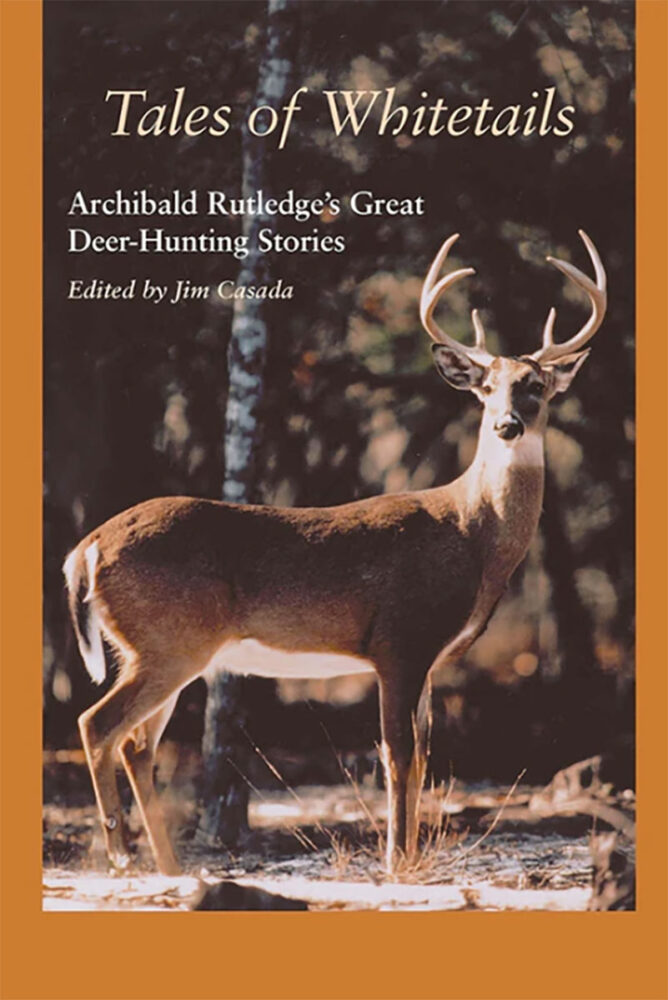

Archibald Rutledge—renowned outdoor writer, poet laureate, and authority on whitetails—is again returned to print in this stirring collection of thirty-five of his finest deer stories. Rutledge, who lived a rich life at Hampton Plantation in South Carolina, had a mystical attachment to deer that found fulfillment in hunting and writing. No American sporting writer has been more persuasive in capturing the myriad, and often elusive, meanings of the hunt. Buy Now

Archibald Rutledge—renowned outdoor writer, poet laureate, and authority on whitetails—is again returned to print in this stirring collection of thirty-five of his finest deer stories. Rutledge, who lived a rich life at Hampton Plantation in South Carolina, had a mystical attachment to deer that found fulfillment in hunting and writing. No American sporting writer has been more persuasive in capturing the myriad, and often elusive, meanings of the hunt. Buy Now