Askew’s Carolina Lady was, and is, the foundation female—the Eve, if you will—of the field-type Irish setter as we know it today.

One day a friend of Ned LeGrande’s stopped by to visit him at his Willow Winds Farm, near Douglassville in southeastern Pennsylvania. At the time—it was the mid-1950s—LeGrande was up to his armpits in the effort for which he’d ultimately be recognized as the savior of the hunting Irish setter and the chief architect of the modern “red” setter.

It was getting on toward evening when the friend noticed, with understandable alarm, that one of LeGrande’s dogs had climbed the fence and was about to make a break for it. This wasn’t just any dog, either. It was Askew’s Carolina Lady, the most valuable animal in his kennel and the cornerstone of his entire breeding program!

The friend was ready to summon the National Guard…but LeGrande barely batted an eye. “She’s just going out to catch a rabbit for her pups,” he explained.

And that’s exactly what she did. Before the sun went down, this future Hall-of-Famer who almost single-handedly transformed the fortunes of her breed was climbing back into her kennel with a freshly killed cottontail flopping limply in her jaws.

Askew’s Carolina Lady placed 28 times in FDSB-recognized field trials, was named the winner of the inaugural National Red Setter Shooting Dog Championship and earned an AKC Field Championship for good measure. But while her comportment afield may have been letter-perfect, there remained something gloriously wild, untamed and even a little bit savage about her.

Of course, if your intent is to reboot a gene pool that’s lain stagnant for close to half-a-century, infusing the blood of a borderline renegade with white-hot prey drive is a pretty good place to start. The story’s been told many times, but by the late-1940s the hunting Irish setter, historically equal in every respect to the English setter and the pointer, had largely passed from the American scene.

What had happened? Well, to put it as simply as possible, the Irish setter had become a victim of its own beauty. Its breeders emphasized coat, conformation and looks—the qualities prized in the show ring, essentially—at the cost of virtually everything else and as a result, the red dogs’ once-vaunted hunting prowess eroded to a pitiful remnant of what it had once been. By the 1940s many Irish setters wouldn’t even point, and even when they did, they were so lacking in style and intensity they looked like they were waiting for a bus.

They were awkwardly gaited, too—terms like “lumbering” and “rocking horse” were commonly used—which not only hampered their ability to get over the ground and hit the birdy places but absolutely killed their stamina. The bottom line is that from a hunter’s perspective, the Irish setter of the mid-20th century was, for the most part, a pretty sorry animal.

Which brings us back to W.E. “Ned” LeGrande. Born in Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1911, he’d grown up hunting quail behind the kind of Irish setters that used to be described as “good country bird dogs.” But he drifted away from the sport until his curiosity got the better of him one day and he took his wife, Helen, to check out a field trial restricted to Irish setters—all of them, as was typically the case in those days, from bench stock.

What LeGrande saw appalled him. As he recalled years later, those bench-bred setters “looked like they were bred to pull a milk wagon in harness rather than to be taken into the fields to shoot a mess of quail over…short on nose, deficient in point, and without exception equipped with pump-handled tails.”

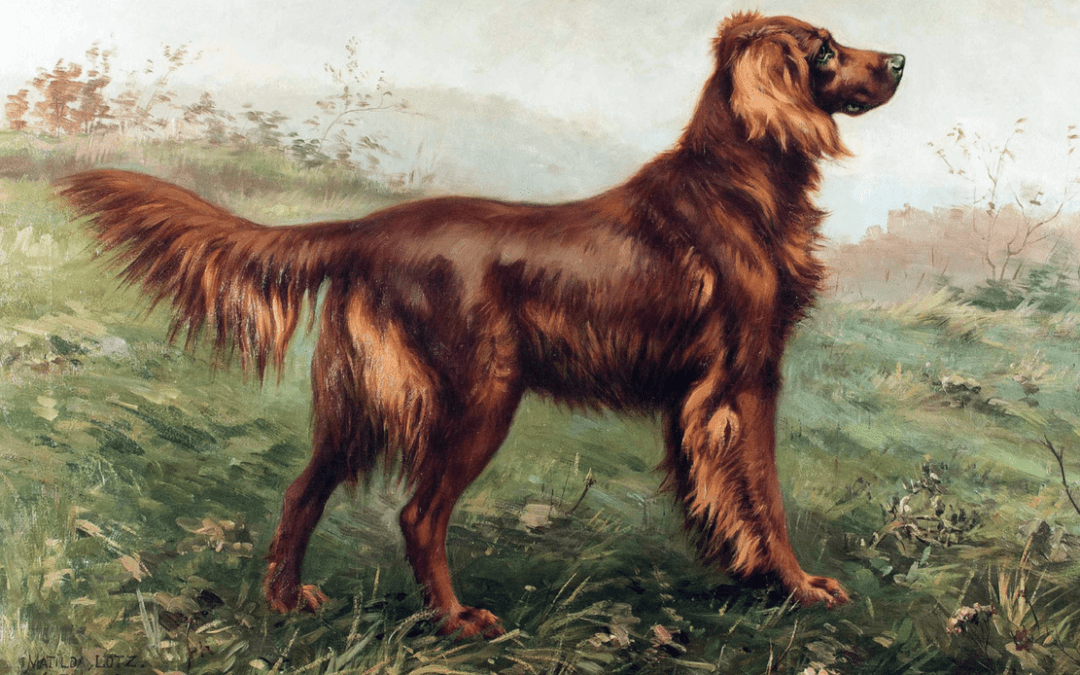

Askew’s Carolina Lady

It was while watching this sad charade of a field trial that Ned LeGrande—a big, handsome, charismatic guy who’d been a star football player at the College of William & Mary and was now a successful business executive—turned to his wife and made a proclamation that would change the course of bird dog history.

“Something,” he said, “has got to be done about the Irish setter.”

And, in that imponderable way fate has of finding the right person to meet the challenge of a certain historical moment, LeGrande was just the man to do it.

By 1952, LeGrande had assembled a small nucleus of field-bred Irish at Willow Winds Farm. Even in the breed’s darkest hour, a few diehards had kept the old bloodlines going, breeding a litter every now and then and selling the pups (or simply giving them away) to local bird hunters. The problem for LeGrande was that, because these men weren’t in it for the money and tended to live in isolated rural locations, they, and their dogs, were damnably hard to track down.

LeGrande was nothing if not persistent, however, and by casting his net far-and-wide he managed to find a few setters that met his criteria. They were solid gundogs…but they weren’t world-beaters. Their most conspicuous deficiency, in LeGrande’s judgment, was that they didn’t point with high tails. A level or slightly elevated tail was an absolutely fine attitude for a hunting dog on point, but if the red dogs were to have any hope of putting a scare into the white ones in field trials, their tails had to come up.

Through advertisements in The American Field and other outlets, LeGrande spread the word that he was in the market for field-bred Irish setters that pointed with high tails. He looked at dozens of dogs and rejected every one of them. Then he got a tip from one Hunter Grove, a professional trainer in North Carolina. Grove told LeGrande that there was a farmer in Enfield, NC, whose Irish setter female was the best quail dog in those parts—and she pointed with a high tail!

LeGrande drove to North Carolina, only to be told by Lady’s owner, Kelsey Askew, that she wasn’t for sale. As dog men are wont to do, though, he was happy to show her off, and when LeGrande saw her slam into point on the “home place” covey he could barely contain his excitement. She pointed not just with a high tail, but with the kind of electrifying intensity that raises the hair on the back of your neck. On the smallish side, she had ideal conformation for the field—and it was obvious that she didn’t have a speck of show blood in her. She was athletic, animated, light on her feet….

It took a while, but at last the two men came to terms. “He didn’t want to let her go,” LeGrande recalled in a 1978 interview. “But we sat down over a jug of cider and finally he said, ‘Everything I raise is for sale.’”

What LeGrande couldn’t know then, but would learn in breathtakingly short order, was that in Askew’s Carolina Lady he’d found his pot o’ gold. She posted a sterling record in field trial competition, but as a producer she blew the roof off. She was the quantum leap forward for her breed: If the hunting Irish setter pre-Lady was an oxcart, post-Lady it was a Porsche. She was, and is, the foundation female—the Eve, if you will—of the field-type Irish setter as we know it today.

In 1972, 14 years after her passing, Askew’s Carolina Lady received the ultimate honor when she was elected to the Field Trial Hall of Fame. Many people who know more about this stuff than I do will tell you that the quality of today’s field-bred Irish setters is better than it’s ever been. Some even insist that, dog-for-dog, the reds are the best pointing breed going. Of all the ways you can frame the remarkable legacy of Askew’s Carolina Lady, that strikes me as the one that says the most.

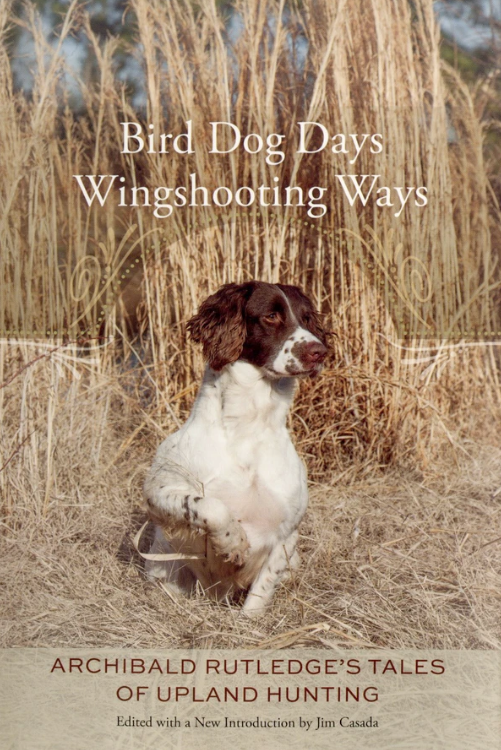

Archibald Rutledge has long been recognized as one of the finest sporting scribes this country has ever produced. A prolific writer who specialized in stories on nature and hunting, over the course of a long and prolific career Rutledge produced more than fifty books of poetry and prose, held the position of South Carolina’s poet laureate for thirty-three years, and garnered numerous honorary degrees and prizes for his writings.

Archibald Rutledge has long been recognized as one of the finest sporting scribes this country has ever produced. A prolific writer who specialized in stories on nature and hunting, over the course of a long and prolific career Rutledge produced more than fifty books of poetry and prose, held the position of South Carolina’s poet laureate for thirty-three years, and garnered numerous honorary degrees and prizes for his writings.

In this revised and expanded edition of Bird Dog Days, Wingshooting Ways, noted outdoor writer Jim Casada draws together Rutledge’s stories on the southern heartland, deer hunting, turkey hunting, and Carolina Christmas hunts and traditions. Shop Now