The very nature of hunting requires that you know as much as possible about the game you pursue. And that’s why, the author maintains, artists who hunt are able to capture the essence of their wild subjects.

For the past few decades, wildlife art has enjoyed an unprecedented boom. Public acceptance and demand have never been so high. Many books have been published on the subject, and today, dozens of magazines feature wildlife artists and their art.

Wild Boar by German artist Manfred Schatz.

When viewing the work of an artist, whether in a book or periodical, the reader mentally separates the really striking pieces from the mundane. Some images create a strong impression simply because the artist was clever or used a gimmick to grab the viewer’s attention. Other pieces attract the eye because they project an intangible “something” that appeals to the viewer.

It would be an oversimplification to say that anyone factor makes the viewing public feel more strongly about one work of art versus another. However, there is one factor that shows up with uncanny regularity in the best wildlife and sporting art: the aspect of hunting. Nearly all of the animal artists who create convincing paintings on a regular basis either are hunters, have been hunters but no longer are, or at the very least, think like hunters.

Hunters love the out-of-doors. To them, the quest for game is an integral part of their life. The very nature of hunting requires that you know as much as possible about the game you pursue: habits, habitat, food preferences, feeding times, what attracts, what repels. Hunter-artists typically know more about their subjects than do non-hunting-artists.

Non-hunters in general tend to take a far too simplistic view of the hunter-quarry relationship. They fail to understand how a hunter can respect and love the game he chases, yet be able to kill it. Admittedly, it is an extremely complex relationship, one that defies description; yet it is thoroughly understood by virtually every hunter. This “mystic” connection gives the hunter-artist a distinct advantage over the non-hunter-artist, which is evident in the finished work of each.

Non-hunter-artists also tend to view animals anthropomorphically-that is, they ascribe human values and characteristics to their animal subjects. Their work leans toward the cutesy side — bear cubs playing among wildflowers with butterflies enacting an aerial ballet around them, a red squirrel chattering from atop a tree stump, a blue jay scolding from high in a flowering dogwood.

Animals do what they do from instinct and from mimicking the adults. They do not know about Bambi or Thumper; they aren’t aware of wives or husbands; they hold no special love for, or loyalty to, a brother or sister. Their sole purpose, whether through instinct or learned behavior, is survival. They mate, not because they want to experience gratification, but purely out of instinct to perpetuate the species.

Artworks that depict “love” between animals are occasionally humorous and usually trite. Such situations are rarely executed by hunter-artists, which further underscores the fact that these artists have deeper insight into the true nature of their subjects than do non-hunter-artists. Humor in wildlife art is perfectly legitimate, so long as the humor comes from the artist, not the animal subject. Wild creatures may do funny things, but they do not perform for humans and other animals.

Setting Decoys by Frank W Benson.

Going back through the history of European wildlife art, a number of greats come to mind: Sir Edwin Landseer, Wilhelm Kuhnert, Bruno Liljefors, Archibald Thorburn, Sir Peter Scott, George Lodge. All were avid hunters at least part of their lifetime.

Among past masters in North America are John James Audubon, Frank Benson, A. Lassell Ripley, Ogden Pleissner, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Francis Lee Jaques, and Carl Rungius. Again, they all hunted at one time or another.

In fact, most of them not only hunted, but skinned and dissected wild specimens so they could scrutinize muscle placement and structure. They studied animal skeletons for proportions and position of bones and limbs. They made many reference drawings of fresh kills and anatomical drawings of skinned specimens. They preserved bones, body parts, and skins for future reference. Their paintings reflected anatomical accuracy as well as the essence of the animal.

Carl Rungius, for one, would suspend a dead animal with ropes, then maneuver it like a marionette into various positions for sketching. His finished works reflect his love for the outdoors and the game he hunted in a convincing and realistic manner.

Artists who hunt have more than just a superficial respect for the animals they paint. When pursing wild game, they pit human reasoning against the animal’s survival instincts and special attributes-speed, ability to fly, raw power, superior senses-in a contest that will result in life or death. To be successful, the hunter must think like the hunted. He must know how the game acts and reacts; he must be aware of every little nuance which is characteristic of that species.

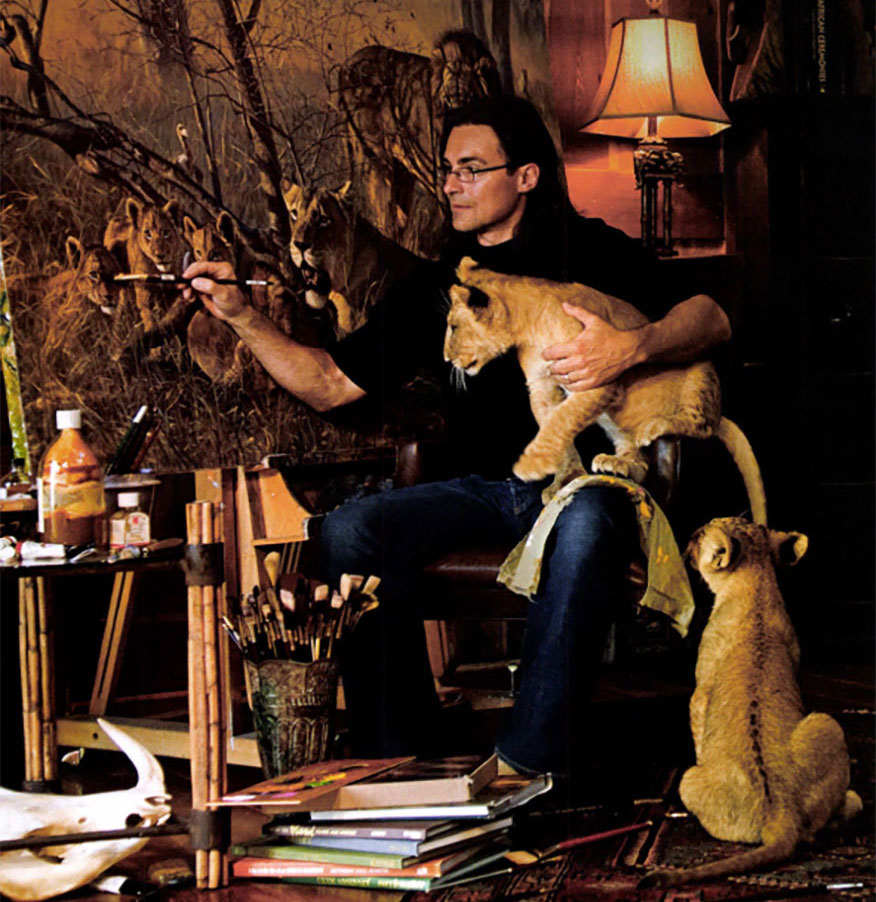

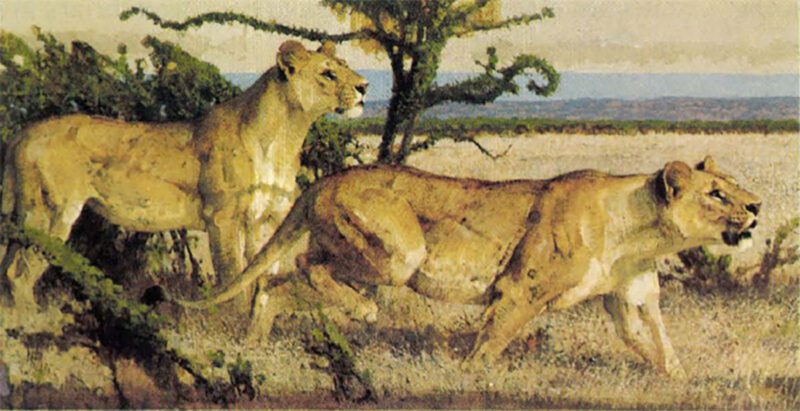

In his introduction in the “Masters of the Wild” book, The Art of Bob Kuhn, Bob Abbett, an excellent sporting artist in his own right, tells about Kuhn’s awesome knowledge of animal anatomy and his ability to almost creep into the minds of his wild subjects. He quotes Fred King, owner of Sportsman’s Edge,Ltd./King Gallery in New York City, as saying: “In a Bob Kuhn painting you see the animal and the setting as they should look. They’re never ‘squeaky clean’; he makes you feel the dust and the heat (or cold) — you can almost SMELL the animal.” Kuhn has been a hunter most of his life. He is renowned for his paintings of the big cats in which he captures the character of the feline. Bob’s ability to convey the electric personality of wild cats stems largely from intimate knowledge gained by stalking them, though he admits to never having killed any of the big cats.

Ken Carlson and Manfred Schatz, two undeniably fine wildlife artists, hunted early in their careers, but both found it difficult to hunt and to do a credible job of sketching at the same time. Each chose to forego hunting for fieldtrips expressly for sketching. On the other hand, such notable sporting artists as Chet Reneson, John Cowan, and Thomas Aquinas Daly continue to be active and enthusiastic hunters.

In his book, Jagdtage (Hunting Days), Schatz describes the difficulties encountered in the pursuit of game: snow, sleet, driving rain, dense underbrush, biting insects, etc. Few non-hunting wildlife artists are willing to suffer the rigors of a hunt simply to observe the subtleties that wild animals display when they think they are not being observed.

No wild animal acts the same in captivity as it would in the wild. Predators, both mammals and birds, are especially vulnerable to personality changes in captivity. Many become sluggish, some become fearful, some become overly aggressive. Many animals also change physically: bones in their feet break down, they become flabby, fur becomes lackluster, teeth change position due to unnatural diet and muscles atrophy. They lose much of their wildness.

Paintings created strictly from photos of zoo animals and semi-tame animals found along roadsides in the country’s national parks often lack the “spark” found in truly wild animals. A great many commercial artists are quite capable of copying a photo of an animal with hairline accuracy in every detail. However, not only is that not art, but the finished product lacks the essence of the animal and results in simply a “pretty picture.”

Bob Kuhn’s Closing the Distance. Few contemporary wildlife artists can recreate the tension in lions stalking their prey.

David Maass’ waterfowl and game bird paintings have become legendary among collectors because they convince the viewer that he is observing wild birds in their natural state. Dave has hunted feathered game most of his life, and the additional understanding he has gained over the years is obvious in his paintings. He has spent countless pre-dawn hours in sub-freezing weather waiting for a flight of blue bills or mallards; he has endured innumerable scratches from briars in search of grouse and woodcock, and no matter how tired, he has worked into the night cleaning the day’s take. These are the things that bring a hunter-artist closer to a true understanding of his subject. Viewers of Dave Maass’ paintings recognize that the artist has “been there.”

The bottom line is that artists who only hunt with a camera rarely, if ever, develop the insight to capture the soul of an animal on canvas. They see only the physical aspect of their subjects. But then again, they’re only passing through the wilderness world; the hunters live there.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1990 May/June issue of Sporting Classics.

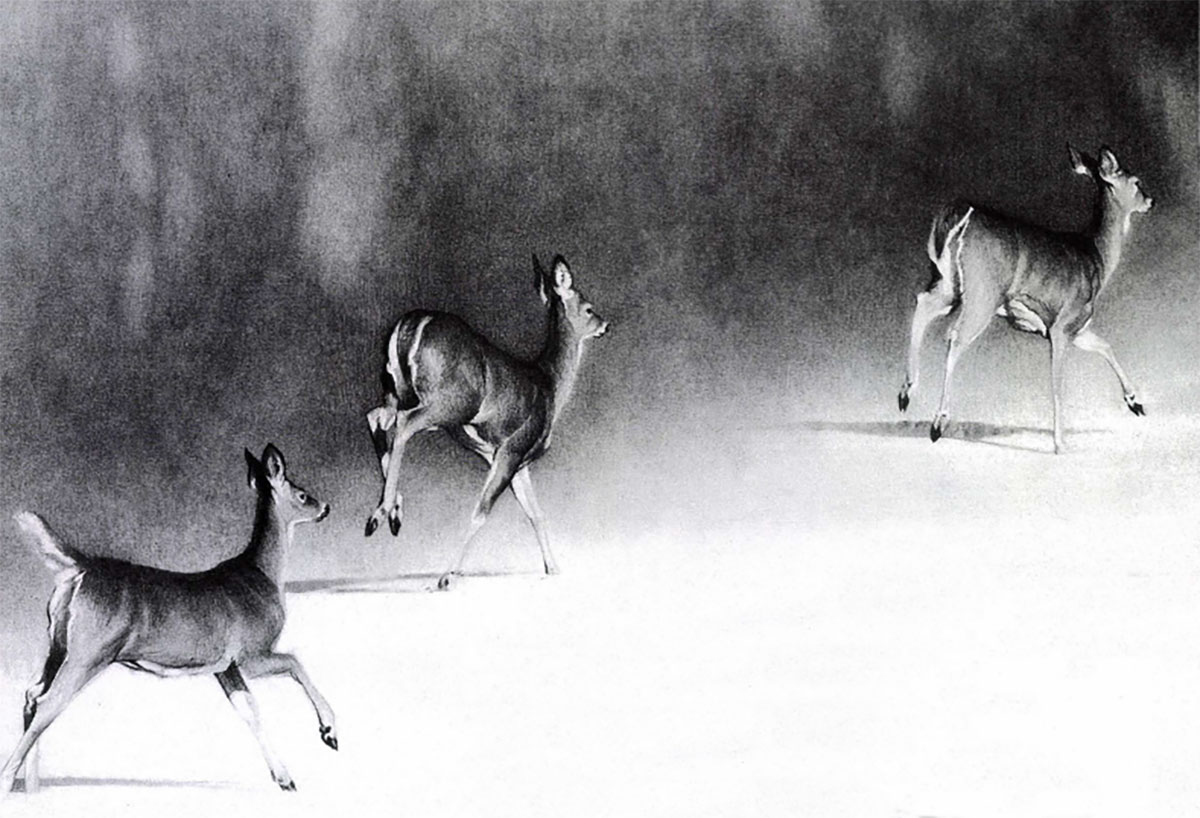

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now