Returning to his favorite squirrel woods after 40 years, he would rediscover the land and a few things about himself.

Dank black pools of standing water enveloped the timber, mostly oak and hickory. The trees were massive in their maturity, casting the woodlot and its single human inhabitant with a spell of enchantment. The chilly air was crisp with autumn, its rich aroma pungently paired with the decay of the morass. In the shadows I could see indistinct flickers of movement, which soon revealed themselves as squirrels. Fox squirrels…and in eye-popping numbers.

By the time shooting light arrived, the squirrels had scurried into the crowns above me, on the ground before me and everywhere in between on their arboreal flying trapeze. Never before had I seen such squirrel nirvana. I shot from a single location and marked them with memory where they fell, stopping at five. Later, I still-hunted the border of a cornfield, stalking a squirrel whose chirp was curiously bass in tenor. I soon spied it in the crook of a distant branch, and when that sixth and final squirrel tumbled freely into the air, it looked so big that I thought I’d shot a tree-dwelling groundhog. It landed like a sack of flour. I had just taken the largest fox squirrel I had ever seen and the largest I would see for at least the next four decades…for that’s when all of this happened; more than 40 years ago.

I was a college student then, far from home and familiar haunts. I had been looking for a place to hunt, an escape from campus and a means to forget about responsibility now and then. A few casual inquiries with locals soon had me knocking on a farmhouse door. The man who answered had square features, thin dark hair and a kind expression. He regarded me curiously as I explained that I was a college student looking for a place to hunt.

“Do you know of any good squirrel hunting you could point me to?” I asked.

“Squirrels? The man suddenly smiled. “Oh, yeah. I sure do.” And then his smile grew broader.

After explaining the details of his boundaries and a final admonishment not to shoot any pets, he granted me access to what would become one of the most remarkable hunting areas of my life. I’d never find a more productive squirrel woods, where fox squirrels outnumbered the grays and grew to such impressive size. But more importantly, that parcel of swampy timber became something of a personal oasis at a formative time of my life; and though my time there lasted only four seasons, it was a magical place I’d forever cherish in memory.

I thought of that little woodland many times over the years, and I fantasized about someday returning. But life has a way of interfering with such wistful musing, especially when tempered by inevitable probabilities like the passing of ownership or timber cutting that would have destroyed the land’s productivity and charm. So it lay on the back burner for decades until one fall when a bit of serendipity intervened.

It was the weekend of my college homecoming and, having nothing pressing to do on that particular Saturday, I considered making the trip to my alma mater on the off chance I might run into some old fraternity brothers. But I was ambivalent about going, and as I drove along the interstate, I found myself thinking less of old college friends and more about old college hunting. Once again I thought about the vaunted squirrel woods, only to have an epiphany. What’s keeping me from going there right now to have a look at it? In a moment of spontaneity, I decided to embark on a different sort of homecoming.

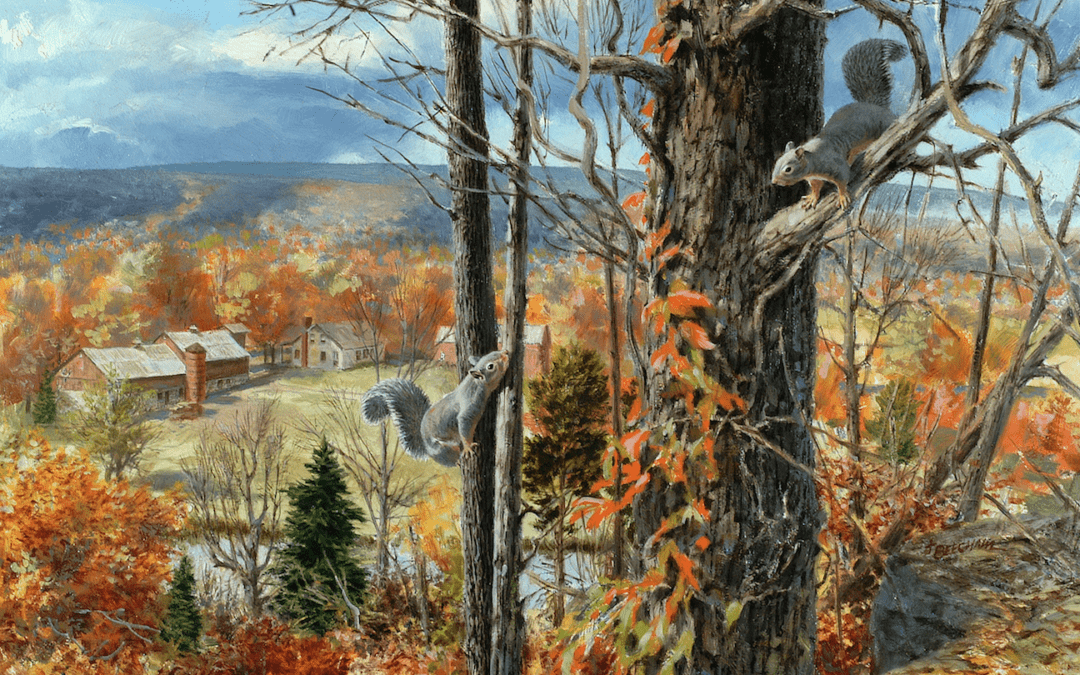

Squirrels in a Tree by Archibald Thorburn

I recalled the way easily and soon found myself looking at the hayfield where I used to park and the sturdy tree-line beyond, as beckoning and enchanting now as it had ever been in memory. I recognized the old farmhouse where I first obtained permission, and then I noticed another house, newly built across the road and closer to the woodlot. The front door was ajar, meaning someone was there. I found myself pulling into the driveway and calling through the screen, “Anyone home?”

An older man came to the door. He seemed annoyed at first, but he softened somewhat as I explained my history with the property. I inquired about the current owner and was delighted to find that I was speaking to him. He told me that it was his father, long deceased, who had given me permission to hunt so many years ago.

That’s when I recognized in him the same square features, the thin dark hair and the kindly face of his father. There was a woozy time rush as I struggled to comprehend that this old fellow was the son of the middle-aged man who first gave me permission to hunt here. This one’s name was Barry. Then I asked him something I hadn’t planned to ask, but certainly had to ask because I now realized it was the whole point of my being there.

“Barry, do you think it would be possible for me to come back and hunt here again?”

The question seemed to pain him. With a shake of his square head, he replied, “No. I can’t give you permission. I have relatives who bow hunt here, and I don’t have a say in it. They make all the decisions. It’s archery season now, you see. I’m sorry. I definitely can’t.”

I had been hopeful, but now my heart sank. Nevertheless, I lingered to talk for a minute; a long minute that grew to most of an hour. Barry turned out to be an interesting and affable guy, and he seemed to enjoy this opportunity for company. We talked of everything from farming to hunting, from politics to his service in Vietnam. He told his war stories and became visibly emotional in remembering friends he had lost there.

For my part, I shared that I was a freelance outdoor writer, and I floated the idea of wanting to write a story about a guy who went back to an old hunting spot after 40 years just to see how things have changed. I gave him my card as a rainstorm threatened to end our conversation.

Then Barry curiously said, “You can park here in the driveway when you come back.”

I was nonplussed. “Are you saying I can hunt here after all?”

He beamed a little. “Yeah, I will talk to my relatives. I’m sure it will be alright.”

I could hardly believe it. Something I had quietly yearned for my entire adult life had come to fruition on a mere whim. It was an unexpected day of destiny. I would see my old woodlot once again. A college homecoming is always a bit of a farce. We go there to celebrate what was but can no longer be. We return to the campus only to find that others have taken our place; therefore, we reminisce but no longer participate.

A hunting homecoming is different. There’s still the satisfaction of remembrances. There’s still the intrigue of contrasting perspectives. But delightfully, we’re still part of the scene as well, as much a participant today as we were in our former lives. That’s the beauty of a hunting homecoming.

I plotted mine with great zeal, waiting for good weather and leaving in the middle of the night for a full day of opportunity to recreate the nostalgic memories of youth. In that I was hopeful but not expectant. Truthfully, I didn’t know what I would find there. Most likely I would see changes, both in the land and in myself. I was prepared for that. I knew this would be less of a hunt and more of an experiment to test the measure of time against the true nature of all things. It was to be an adventure of discovery.

I had dreamed of it for so long that I arrived that morning with butterflies in my stomach. The day was barely breaking when I parked my truck in Barry’s driveway, being careful not to shine the headlights on the house or slam the doors. With my .22 slung atop my shoulder and enough food and water to last the day, I crossed the back field to the edge of the timber, and with a pause and a deep breath, gingerly stepped into a personal time portal.

First there was a small creek to cross. I remembered that when I saw it. Then I began looking for familiar paths and the young man who once trod them. But the first thing I encountered was a trail camera pointed directly at me, a firm reminder that it was no longer 1978. I gave it a wave and a smile and continued on.

There was evidence of logging. Rotting treetops, heavy understory and skidder scars told the story of the not-too-distant past. But as my wanderings widened and my old haunt gradually revealed itself, I marveled over how much of that big timber had survived. The stately groves of oak and hickory still stood much as I remembered them along with stands of mature beech along the fringes.

In the old days, these woods came alive at sunrise with squirrels scampering everywhere. It was common to have a limit by noon. But that was in sunny weather. This day was overcast and breezy, and a full hour passed before I saw my first squirrel. Shooting it was difficult. I was a long time tracking its movements through the scope before I could finally press the trigger.

As a young man, I used a shotgun because killing squirrels mattered. Now, as an old man, I use a .22 because how I kill them matters more, and the killing itself doesn’t matter at all. Being there is all that matters, and being in this particular place in this particular moment mattered a great deal.

At the shot, the squirrel disappeared, and I feared a miss, but on the other side of the tree I found a boar fox squirrel lying on the ground. I had done it!

In that moment, the past and present were fully reconciled. I could have finished then and been content, but the day was still young, cool and damp, still full of autumn and full of promise.

As I ventured farther, I saw more trail cameras and numerous treestands but no hunters in them. I could only wonder how many times my photo was taken and what the owners of those cameras would think of my invasion of their perfectly monitored deer habitat.

When answering calls of nature, I looked around carefully to make certain no digital eyes were watching. Woodlands like this once provided our only escape from our often-hectic lives, but that’s no longer the case. Today, our every move is monitored.

I suddenly remembered the only bow hunter I had ever encountered there in the old days. I saw him on two occasions, both times in the same place. He was squatting on the ground, hunkered under the boughs of a pine tree, watching the trail in front of him. He wore a green plaid jacket and held an elegant recurve in a ready position. Both times he smiled and waved as I passed him. I remembered that hunter and considered how much the sport of bow hunting has evolved over the decades. I considered that and many other things as I wandered, paying little attention to my direction of travel, losing myself in thought and reminiscence, losing myself in the joy of being there, and eventually losing myself in the swamp.

I stupidly thought I would remember my way around. But after a 40-year absence and with no sun or terrain features to guide me, I became thoroughly disoriented. By the time I straightened things out, I had lost considerable hunting time and walked many fruitless miles. I decided to sit for a while.

The author’s custom .22 Remington Model 547 and a morning’s bag of squirrels

I went to a place that had always been a hot spot. The big trees were still there, growing from high ground amid the black, stagnant pools; still producing the mast that produces the quarry. I waited quietly and soon spied a fox squirrel, and then another and then another. I tried moving closer to one of them when suddenly a fourth squirrel appeared on a log not 10 yards away. A quick offhand shot added the large male to the game bag.

Now the squirrels were fully active. They crisscrossed the swamp in their random travels, and I stalked them one at a time. As I would lose track of one, I’d soon pick up another, so that once again I was randomly drifting through the timber as I had that morning and as I had always done as a young man back in the old days.

The memory of that young man was with me, and I noted with pleasure that I still moved with the same purposeful stride and careful economy of motion. My patience seemed no greater and no lesser than it had been since the last time I visited these woods. I recognized in myself the same temperament that I recalled from that time, the same outlook and the same spirituality embedded in this endeavor.

It was curious to me that after all the monumental changes that 40 years brings to a man…a career, a wife and children and now grandchildren—the countless joys and bitter struggles that are universal to all of us in that chunk of a lifetime—it was curious to discover that the hunter inside of me had survived it all. Or was it that an essential part of me had been preserved by hunting?

Later in the afternoon, I worked my way back to the entrance of the woods. Along the way I saw a few more squirrels rummaging the understory. After a short stalk, I managed to shoot a third fox squirrel that dwarfed the others I’d taken. This was the culmination of the hunt. To try for more was to drink too deeply.

My long-awaited return had been a success. What had grown obscure after 40 years was clarified and found to be without mystery after all. The woods were largely the same, and apparently so was I. As I crossed the field on my way to the truck, I joyfully planned an annual reunion with this treasured place.

Barry was out burning stumps in his pasture. I put my gear into the truck and walked out to greet him and to make my request to come back for a single day every year. For his generosity I’d keep him well stocked in homemade pie. Such was my plan, but when I got there Barry seemed upset.

With sad resignation he said: “We have a problem.”

He then told me that one of his deer hunting kin was furious with him for allowing someone else onto the property.

“They don’t want anyone messin’ up the deer huntin’ here,” Barry added.

“So does this mean I’m done?” I asked.

“I’m afraid so. I can’t let you come back.”

Poor Barry seemed truly miserable, and I was too.

I had expected my old stomping ground to be drastically altered, but it wasn’t. I had expected a terrific contrast between the young hunter who roamed there many years ago and his aging counterpart in the present, but there was none. Surprisingly, the only change I had discovered after 40 years was in hunting itself.

The somber lesson to every homecoming is that you can never really go back. In my case, that’s quite literally true. And it’s true for all of us as technology and our hunting culture continue to evolve, slowly transforming the way we hunt; slowly transforming our priorities and our values; and slowly transforming some of us into anachronistic dinosaurs who stubbornly persist in a more fabled version of America’s woodlands.

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman, William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach and more. Buy Now

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman, William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach and more. Buy Now