Image courtesy of Horst Held Antique Firearms

Imagine a Glock with its magazine stuck perpendicularly through the slide instead of inside the grip. That’s a harmonica gun.

The design was an early attempt at high-capacity firearms. Harmonica guns were made with a steel magazine of sorts with each shot charge in its own housing. Metallic cartridges weren’t in use yet, so the separate powder, primer, and projectile were placed into the magazine’s nine to ten chambers.

There were two predominant versions of the design: one with a single barrel and sliding magazine; the other with each chamber of the magazine functioning as its own barrel. The harmonica style could also be had in either a pistol or rifle. Texan Sam Houston owned a rifle that has since been included in the Smithsonian.

The firearm came at the end of the loose ammo period and was rendered obsolete by the invention and widespread use of self-contained cartridges. It’s awkward shape didn’t help. Users could not easily conceal the pistol version, which was in direct competition with six-shooters of the era.

Several manufacturers produced the harmonica gun over the 1800s. The most notable name on the list is Jonathan Browning, father of the world-famous John Browning. John went a different direction with his Model 1911 and forsook the external magazine of the harmonica gun. Imagine what might have happened if John incorporated Jonathan’s magazine into the 1911 using self-contained .45 ammo. Modern pistols could have been dramatically different—and drastically more cumbersome.

Here’s a demonstration of how the harmonica gun functioned:

Video courtesy of Forgotten Weapons via YouTube

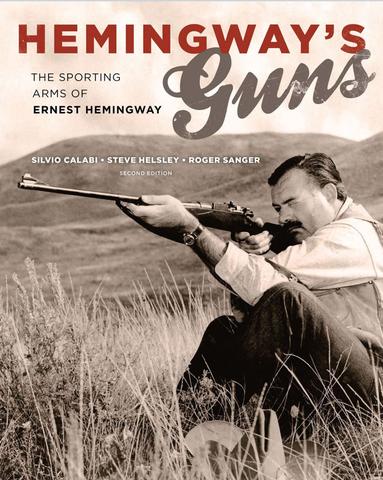

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Ernest Hemingway’s friend A.E. Hotchner once described a “yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest,” shown him by Hemingway, “aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 2½ and when 4 could handle a pistol.’”

Firearms and shooting infused Hemingway’s existence and thus his writing. He was a member of his high-school gun club and went to war when he was eighteen. He hunted elk, deer, and bear in the American west and went on two extended African safaris, which figured hugely in his writing and changed his life. To the day of his death, Hemingway remained an avid hunter, first-class wingshot, and capable rifleman.

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Buy Now