Pursuit of the tiny African parasite had fallen to his drinking buddies, who found it an amusing— though quite dangerous—game.

Wait a minute!” said Bucky Blackrod. “I can feel it moving now. Get ready. Okay, nail the bastard!”

A group of drunks lunged at his hairy bare leg, propped on the scarred lip of the bar. Clumsy hands matched and groped. Irish curses blued the air.

“Missed him!”

The worm had emerged from the edge of Bucky’s shin, waving up into the boozy light with its pointed, eyeless head—a thin red ribbon fully a foot long. But at the attack, it had once again retreated.

It was a Guinea worm, Dracunculus medinensis, an African parasite that had plagued explorers ever since the days of James Bruce, the 18th-century Scot who had been the first white man to reach the source of the Blue Nile in Abyssinia. Bucky had acquired his unwanted passenger during a safari in Central Africa three years earlier. Doctors could do nothing about it; the worm was impervious to drugs or medication of any kind. It lived in his legs, migrating from one to the other in a slow, tingly crawl occasionally punctuated by a stab of pain, like a hot needle run through his veins. Toward evening, it would often emerge from his skin for a look around. But usually, toward evening, Bucky was halfway in the bag, too slow with drink to catch it. Thus the pursuit of the Guinea worm had fallen to his drinking buddies, who found it an amusing game. Unfortunately, most of them were slower than Bucky. Retired cops, laid-off stevedores, sailors on leave, cab drivers, just plain bums— they had been drinking since nine in the morning when Clancy’s opened. Clancy, a tall, cadaverous, big-knuckled man with a slab of patent-leather hair across his pale forehead, never drank, but even he could not catch the Guinea worm and had long ago given up trying.

“Maybe he’s waiting to get back to Africa,” Bucky said, ordering another shot to go with his beer. “I’ll be over there by the weekend. Maybe he’ll come out and go away. Go get himself a girlfriend.”

“Yes,” said Clancy from behind the bar. “I suppose you’d call a female of the species a Guiness worm.”

“I still say you should let me try this,” said Riordan, the veinous ex-cop. He patted the .38 Police Special in the quick-draw clip at his hip. The butt of the gun peeked out from under a roll of fat in a dirty shirt. “He can’t be quick as a bullet. We’d let him come out with the bar as a backdrop and I’d blow his soddin’ head off.”

“Clancy wouldn’t care for that,” said Bucky, tossing off his rye. “And anyway, Riordan, you’d probably blow my soddin’ leg off.”

Riordan bridled, his red face going purple as the others chuckled.

“For thirty years I was the best pistol shot in my precinct,” he growled. “From the Bowery to Fort Apache, from Harlem to Sheepshead Bay, I could do it. Bucko me lad.”

“A sawbuck says you miss,” piped Schultheiss, the crippled ex-elevator jockey. He slapped a ten-spot on the bar. The sailors chimed in, laying singles and fives on the pile, arguing odds and laying off one another’s bets. Bucky peeled a twenty from the inside of his roll of expense money for the upcoming safari and smoothed it atop the pile.

“Half the pot goes to Clancy, to fix the bullet hole,” he said. “And the cops. All right, Clance?”

The bartender walked to the door, looked up and down the street, then pulled the shades.

“We can say it was a holdup man,” he said.

“Shhhh,” said Bucky, pulling up his pants legs. “He likes the quiet.”

The other drunks staggered off away from the bar. Riordan drew his pistol and crouched on the hardwood floor, clearing a space for his shoes in the sawdust. He held the pistol in a double-handed grip, his elbows locked and lying across his knees, the muzzle far enough away from Bucky’s bare leg to avoid flash burn. Clancy poured a shot for Bucky and another for Riordan. The Irishman shrugged it away. He wanted to be dead calm.

Silence fell over the saloon, apart from the odd hiccup—Maynard the one-time bicycle racer. They heard a siren go up Eighth Avenue. They heard two hookers giggle down the avenue. Flaherty, who had flown 36 missions as chin-turret gunner in a B-17 during World War II, struggled to stifle a beer fart. They waited.

The Guinea worm poked its head out of Bucky’s knee. It swayed in the dim light, retreated a bit, then emerged slowly. It came out like a cobra from a fakir’s basket, weaving to a music beyond the range of human ears. It was actually quite beautiful— slim, sinuous, graceful almost, a nearly translucent red, like a living thermometer. It hypnotized them with its dance.

Riordan shot.

They all jumped at the bark of the revolver. Bottles shivered on the bar. The clouded mirror shifted an inch to the left. Clancy’s black leather bowtie took a ride on his Adam’s apple. Flaherty cut his fart.

The Guinea worm, minus its head, whipped back into Bucky’s knee like a snapped rubber band.

Later, walking up Eighth past the porno houses and the hooks and the muggers, who paid him no attention because of the blood and beer stains on his clothing, Bucky thought that the Guinea worm would either die inside his leg and rot there, or else grow a new head. It would probably grow a new head. It was that sort of animal. Anyway, he hoped it would. He had come to like it.

He was glad to be heading back to Africa. New York had gotten boring in the past few years. Everybody whined or snuck around behind your back. Even the muggers were yellow. They cut first and took your money afterward. But they didn’t bother him because he was too much of a slob. Only the grungiest of whores would have anything to do with him. He used to be a good-looking guy, but now he was getting fat and he didn’t care about anything anymore. The job bored him: It was games. Politics put him to sleep. He liked to read, but he could do that anywhere. He carried his own music inside his head. His movies, too.

In Africa everything was strong, and it changed all the time. Everything bit. He knew that inside his fat and his lethargy there was a thin, eager young man waiting to be unzipped. The Guinea worm had told him. He knew that once he got to Africa, the man inside would jump out and go running over the game plains, buck naked, with the Guinea worms waving a weird dance around his ankles.

He could see the buffalo bull ahead of him through the heat haze, its huge black head shining, shimmering, waiting.

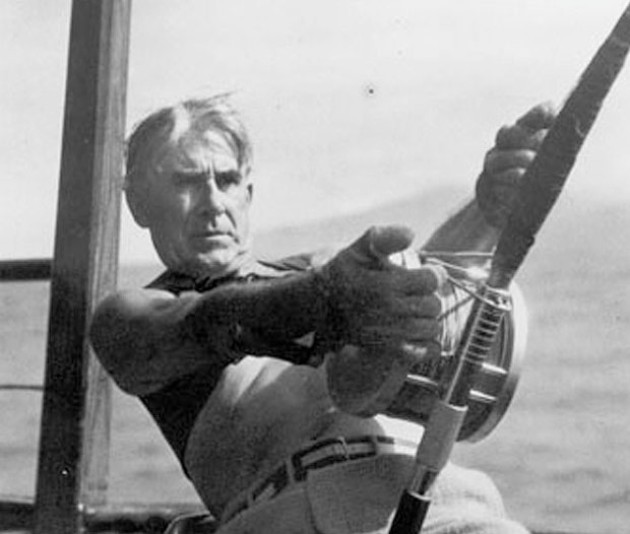

Editor’s Note: This excerpt is from A Roaring in the Blood— Remembering Robert F. Jones, published by Sporting Classics in 2006. Copies of the 205-page book are still available in the Sporting Classics Store.

A Roaring in the Blood – Deluxe Edition $35

A Roaring in the Blood – Deluxe Edition $35 $75

Three years in the making, A Roaring in the Blood: Remembering Robert F. Jones paints a frank, funny, richly textured portrait of this lion of American letters, as seen through the eyes of his friends and as revealed through his own hard-muscled prose. Bob Jones, you learn, was a writer’s writer, a man’s man and a fiercely loyal friend – if not someone whose friendship was always easy. In Jones’ company, you were never far from harm’s way.

And whether you’re among his legions of fans or someone coming to his work for the first time, A Roaring in the Blood, like running the rapids of a brawling North Country river, is a wild – but deeply rewarding – ride. It confirms Jones’ stature as a writer not only of uncommon gifts, but of enduring ones. Buy Now