The following is an excerpt from Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles. Featuring over 40 fictional and true-to-life adventures, the stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Click Here to Order your Copy Today!

Mark Twain’s Huck and Jim survived many adventures as they rafted down the Mississippi River, but Mr. Twain, even at his most fervid, didn’t dream up an encounter with African lions on a river island.

But truth really is stranger than fiction. Had Huck and Jim landed their rude craft on an island off Mississippi County in the Missouri Bootheel in January, 1932, they likely would have been face to furry face with the King of Beasts.

The 1932-33 Bootheel African lion hunt stands as the most bizarre episode in Missouri’s hunting history. It was the Perfect Brainstorm of a wealthy St. Louis businessman with an obsession over big game hunting and the money to make it happen.

Denver Wright Sr. (one of his nine children was Junior) made billfolds, belts and other leather sundries at two manufacturing plants, one in St. Louis, the other in Doniphan.

When he wasn’t holding up the pants of male America, he was afire with the intrigue, glamour and danger of Darkest Africa in the days when big game safaris were the ultimate testosterone test. Although Wright later would hunt worldwide and bag nearly every species of game animal, the Missouri lion hunt was his first foray into the figurative jungle after animals far larger than the biggest native Show-Me wildlife and ones that theoretically could kill him as easily as he could kill them.

Denver Wright’s plan was to acquire a pair of African lions, then release them in what wilds remained in the Missouri Bootheel and hunt them down, safari-style, with gunbearers, beaters and all the accoutrements of a Hemingway-esque adventure. As it would prove, it sounded far better on paper than what it became in actuality.

Wright had hunted Missouri’s indigenous animals as well as moose, but Africa was his dream and, at that time, an unattainable one. “You can’t hunt big game in Missouri, so I decided to supply my own quarry. Just sort of bringing Africa to the United States,” Wright said.

Later in life, Wright reflected, “Some people wonder why a man takes a gun, goes into a steaming jungle, wades around in water for weeks, gets chewed up by bugs, doesn’t eat and is generally miserable—just to outsmart an animal. Well, I sometimes wonder why some men meander around a golf course all day trying to outsmart a golf ball.”

After the Missouri lion hunt and over the next two decades-plus, Wright would visit 82 countries, averaging two such trips a year in search of big game—from polar bears in the Arctic to charging Cape buffalo in Africa. He even brought back wild elephant poop, which he donated to a Branson museum where it still amazes visitors.

One of his 12 grandsons and a namesake, Denver Wright III, today says, “People who might want to fault my Grandfather for such a stunt might well consider that 1933 was a much different world than even 1953, let alone 2009. In the latter part of his life, he continued big game hunting, but he more often than not chose to shoot with a camera.”

One of five children, Denver Wright was born in 1889 in Providence, Kentucky. He apprenticed at 17 to a Cape Girardeau shoemaker—his introduction to leather—and went to St. Louis, spent some time as a news “butcher” (peddler of newspapers) on a train, migrated to Atlanta for a while, eloped with a 14-year-old girl in 1911 (with whom he would have nine children) and moved to St. Louis permanently in 1918.

His leather plant in Doniphan had 300 workers, which undoubtedly made it the biggest employer in the area. Famed tennis player Helen Wills Moody wore a Wright leather sun visor when she won at Wimbledon.

Wright became a licensed pilot at 58 and owned his own plane. He was a police commissioner, school director and a deputy game warden in the days before Missouri’s conservation program became professionally oriented (that happened in 1936 with a citizen-driven Constitutional amendment).

But all those accomplishments paled before the Great Lion Hunt. There were two attempts. The first, in October of 1932, involved two female lions he purchased from a circus. Wright planned to release them in Missouri’s Mississippi County but the sheriff, Jesse Jackson, was less than charmed at the idea of live African lions roaming his county.

Here’s how Time magazine described the first attempt:

“Into the Ozark foothills in a truck went Denver M. Wright one day last week. With him beside the two young lions he had bought from a circus for $75, were two friends, a barber and a plumber. Somewhere in the hills were his two sons, lost. Behind him, horrified, was the St. Louis suburb of Brentwood, where he had long been respected as a manufacturer and a member of the school board. All around him was hostility. In Mississippi County waited a sheriff with an insanity warrant. In Cape Girardeau County waited 800 vigilantes determined that he should hunt no lions there. Over the rough roads of Scott County bounced the truck, stopping now and then while Hunter Wright begged shelter at a farm house. Always there was only one bed. ‘It’s making me look like an inhuman ogre,’ cried he.”

While Time’s story captures the innately weird nature of the outing, it was at odds with other stories (the part about the sons being lost, for example). As a matter of fact, one son, Charles, was a willing participant in the second hunt and applied the coup de grace to one lion. And it’s doubtful that Wright’s home town, Brentwood, cared much one way or another as long as the lions were released more than 100 miles south.

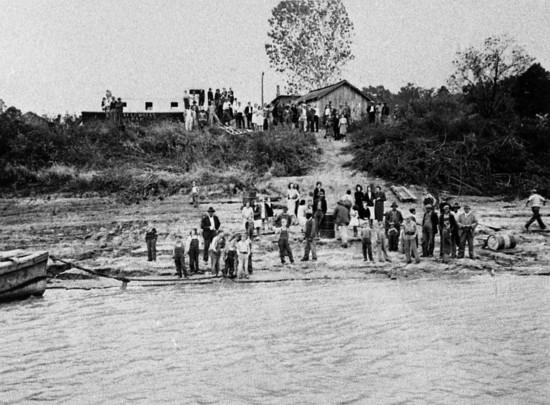

The first hunt with the two young lionesses also featured a chicken dinner and lost opportunity. The 10-month-old lionesses apparently were far less enchanted than Wright with the idea of a get-together in the brush. They cowered in their cage and, as a reporter put it, “sulked.” Wright’s hunting party released Nellie and Bess, the charmingly named lionesses, on a small island in the Mississippi on October 16 and repaired to Commerce, Missouri, for a down-home chicken dinner.

When the hunting party returned to the island, they found lion tracks overlain with boot prints. It was an “uh-oh” moment, which became more suspicious when they found gouts of blood. “Maybe somebody was hurt here,” Wright said hopefully.

No—the two lions had been shot Al Capone-style by a fellow named Walter Wise, one cat lying down, the other just getting to its feet. Wise used a submachine gun provided by the sheriff’s deputy Tom Hodgkiss, who went along for moral support. The two finally ’fessed up and returned the defunct lionesses later in the day. Chances are the execution was sanctioned by local authorities not happy with the idea of lions on the loose.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, having fun with the whole thing, wrote: “So, the lionesses, poor, beaten creatures bought by Wright from a broken-down circus for a $15 drayage fee, had taken it, in a manner of speaking, lying down.”

Wright was nothing if not persistent. He immediately bought two mature male lions, estimated at 450 pounds each, from a north Missouri wild animal farm and set his sights on January for his next safari. Wright wanted to release the lions on 20,000 wooded acres south of East Prairie, but the local citizenry, especially the law enforcement segment, started playing “What if?” Especially, what if the lions somehow evaded Wright’s guns and got hungry? What if the first hearty meal they happened on was some farmer’s prize bull? Or the farmer?

A reporter for the East Prairie Eagle wrote, “Wright has been maligned, praised, complimented and criticized for organizing the hunt. On the one hand a sly desire to see him prosecuted has been entertained. His motive has been questioned. His sportsmanship has been attacked.”

That’s a fair summary of the public’s reaction from St. Louis descending to the Bootheel, with the antipathy swelling the farther south the safari went. According to Time magazine, folks in Cape Girardeau County were as grumpy as those in Mississippi County, recruiting “800 vigilantes determined that he should hunt no lions there.”

Time had a wonderful, well, time with the story: “Newshawks asked Hunter Wright if his lions were real. “’Well,’” said he, ‘they look like lions, and they roar like lions, and they eat like lions. I guess they’re just lions.’”

The second hunt was plagued from the outset by bad weather—it rained almost constantly and the road to the river turned to slop. The hunters wound up pushing their vehicles out of one bog after another and finally enlisted a sympathetic farmer to tow them with his tractor.

An unnamed shipbuilder who put together the boat that ferried them to the island hunting ground might as well have apprenticed to the rattletrap African Queen of movie fame (fittingly enough). The boat, to be charitable, lacked glamour. Writer George Conrad Nagel, an obvious fan of Wright who chronicled the adventure in a small booklet, wrote, “A discarded automobile engine furnished the power. A discarded dish pan served to hold in place the stove pipe projecting through the top and acted as insulation against the deck catching fire.”

So far, all the safari lacked was Humphrey Bogart covered with leeches.

Somehow the boat got across to the island with the hunting party and the lions. Everyone pitched in to drag the caged, combined 900 pounds of lion ashore.

“The first night was terrible,” Nagel wrote. “Not because of the accommodations, but the sudden change from modern conveniences, comfortable beds, steam heat, to an army cot in a tent on an island in the Mississippi River on a rainy night in January—one must experience it to appreciate how it feels.”

And the lions, no doubt just as uncomfortable as the hunters, persisted in roaring periodically through the night. No one got much sleep. When the big cats were released, they plowed through a four-strand barbed wire fence as if it were kite string. That somewhat alarmed the hunting party, which had hoped to rely on the fence to keep them safe during the night.

So, armed guards spent much time shining their flashlights into the trees and jumping at every sound. Persistent rain glistened on the trees, looking in the light from lanterns much like the glowing eyes of ferocious lions.

“Throughout the 34 hours following their release from their cage Friday afternoon,” reported the Post-Dispatch, “they [the lions] appeared utterly incapable of living up to the standard expected of hunted lions. They refused to leave the vicinity of the camp, they gamboled before the bewildered members of the party, they insisted on howling through the hours of darkness when Wright’s retinue was already hard put to find dry spots under tents that failed to ward off the drenching rain.”

At one point, all the accounts agree that many of the unarmed members of the hunting party took to the trees, including the mayor of East Prairie. It wasn’t as if the lions were clawing at the trunks of the trees . . . but you never know.

The “hunt” was almost anticlimactic. The several accounts vary, agreeing only that the two lions wound up dead. Nagel’s admiring account said, “Without warning or a moment’s notice he [the first lion] rushed forward directly at Wright, who was nearest to him. Wright quickly dropped to one knee. There was a shot.”

Wright winged the lion, which fled, seriously wounded. Wright’s son, Charles, “finished the lion with a well aimed shot in the head,” said Nagel.

The Post-Dispatch was far less breathless. “One of the animals, less willing than the other, was wounded when it arose from its recumbent position as Wright and his three riflemen got too close. It was finished off by Wright’s 14-year-old son Charles who shot it through the head as it lay on the mud at the water’s edge, bleeding from two body wounds.”

That left one lion and in Nagel’s account it died in mid-air from simultaneous shots from the two Wrights as it sprang at boatman Indian Joe Putnam who was poking it with a long stick. Considering that the hunters had been throwing rocks and sticks at the lions for two days, cornering them at the end of the island with no escape route except back through the hunters, it’s no wonder the last lion made a break for it.

The P-D had it this way: “The other got on its feet after it had been prodded by one ‘Indian Joe,’ a member of the party, and was promptly dispatched by Wright, his son, Ted Bennett of Dorena, Mo., and John Cliffy of East Prairie, who riddled the animal with rifle fire.”

This last account sounds more like the end of Bonnie and Clyde than Hemingway on safari.

Nagel quickly published “The True Story of America’s Strangest Safari,” a 15-page booklet (which today lists for $600 in the rare book world). The booklet is complete with photos of Wright and all the major participants in the hunt. Nagel’s booklet conveniently makes no mention of the Capone-style execution of the lionesses. “Wright merely did the unusual and reaped the pioneer’s crop of adverse criticism,” Nagel wrote and compares Wright to Daniel Boone and Henry Clay, not to mention Abraham Lincoln, all sons of Kentucky as was Wright.

On the back page is an advertisement for The Lure of the Beast, a movie “with sound effects” of the hunt that, according to the booklet, is “being publicly shown in various Motion Picture Theatres.”

The Post-Dispatch reported that it was too dark and rainy for cinematography and its own still photo of Wright shooting one of the lions is so dim as to be almost in silhouette. Charlie Wright, son of Charles, says there was a 16mm film in the family archives, but it was shot on nitrate-based film and restorers “said not to even bring it by their office as it was too unstable and they were afraid of an explosion.”

If there is another copy of the movie, it has vanished into the dusty vaults of forgotten celluloid—a Google search comes up empty. Perhaps somewhere in the holdings of a library, museum or other repository there is a usable copy of this priceless comedy—one can only hope.

Otherwise, the Missouri lion hunt is confined to the rare book market and the squinty little microfilm files of old newspapers. Too bad—when they talk about legendary hunts (the unicorn, the pot of gold and its attendant leprechaun, the Emerald City) someone should say, “Oh, yeah, and of course that lion hunt in Missouri.”

Denver Wright died in March, 1975, secure in the knowledge that he had organized and carried out the only African lion hunt in the history of Missouri . . . and without a doubt the only one that ever will be held.