The spaniel had lived beyond her time. But strangely – to the last – she had acted almost as a puppy.

He had felt the turn of the tide three years before. Felt it more than in the 73 years before them. It pulled against him now, receding rather than rushing in. He could feel the firmament of his life being drawn away, like the sand from your feet as the breakers subside.

Nobody had to tell him he was getting older, that he was less the man that he used to be. That each day was the more to be treasured now. That there were far more behind him than lay ahead.

He rocked slowly in the old Shaker chair, as the clock struck midnight…gazing into the fire, acknowledging that it was almost spent…just as their woodcock season, his and Sally’s. There was no escaping the symbolism. Or the sadness.

Unlike the fire, which he could replenish, throwing on another log and punching it up again to a blaze, a year past was a year gone.

The little spaniel was lying at his feet, as close as she could get to the hearth and the warmth of the pulsing coals, without drifting from his side. She was 15 now. Her bunting days were nearing their close – and worse, the candle of her life was burning low. She had slowed, the pace of her quest no longer the bouncing, darting, scorch-the-coverts cadence of her prime, which had thrilled him so. There were occasions when she fell, trying to cross a log, or working through clotted cover. Each time it happened, it cut him to the quick.

Her body had withered, more and more, with the past two seasons – but not her spirit. That was nonnegotiable. She was merry still, a bit wobblier on her feet, yet firm of desire. He had worked meticulously on conditioning during the summer, taking her swimming most afternoons in the river and for runs through the misty morning meadows. With the dew on the green grass to cool her going. So that when October came, if he rested her generously between times, she could still go a good hour and a half in the best of a mellow afternoon.

So that each time she faltered, she picked herself slowly up and urged her old bones on. On and on. How he loved and cherished that.

In mind’s eye, he could see her as a puppy still, full of flame, bounding over anything that loomed, threading the densest thicket in a flash and blaze. When the birds were in, they went up like popcorn, and after the gun she would sally back with them in her mouth, her tail high and bushed. She had done it from a puppy, delivered more proudly than all the other spaniels he’d known, with that prissy and prancy little gait. That’s how she had gotten her name, Sally. He had thought to name her Gwen.

He studied the old dog’s breathing. It was shallower and more broken, and he watched closely to see that it continued. From time to time, she twitched and whimpered. Maybe she was remembering, too.

“Sally, Sally,” he said softly, letting the words trail to silence. Days a dozen years dead seemed hardly more than yesterday. Turn around and they were gone.

This season was likely her last. There was one more beautiful week of it, and he would relish every moment, though bitter sweetly, as you would the kiss of someone dearer to you than tomorrow, who was soon given to leave, never to comfort your life amore.

How many times he had wished – wished that he could give her years of his own. To see her again in her prime, to have her with him, their small measure more. To see her bouncing happily back to him, the balance of his days, delivering again a bird.

Another hour passed, given to reverie. Then, suddenly consciousness returned, and he was once again aware of the rain on the roof and the growing wind at the eves. The fire was in its last throes, flickering weakly, so he had let it die, banking the coals against the new morning, shuffling off to bed, and now Sally snuggled against the covers, tight with in the crook of his legs.

He did not know how long he had slept, or if he had slept at all. His mind had not disconnected, and he had wandered for an eternity, it seemed, in the throes of meditation. Thinking ever more wistfully of yesterday, dreading how quickly would come tomorrow…and tomorrow.

He did not know how long or far he had wandered. Abruptly, he found himself on a small path in the dark shadows of a deep woods. The path was the color of brooms edge in autumn, and he was bound to follow wherever it should lead. After many miles he crossed a small, wooden bridge. For he was acutely aware of his footsteps on the bare, silver boards, and of the babble of the small brook that traveled beneath it among the mossy-green rocks. He had taken only a few steps more and paused. For the little path had ended, and he knew then something of the reason it had brought him here.

He did not know how long or far he had wandered. Abruptly, he found himself on a small path in the dark shadows of a deep woods. The path was the color of brooms edge in autumn, and he was bound to follow wherever it should lead. After many miles he crossed a small, wooden bridge. For he was acutely aware of his footsteps on the bare, silver boards, and of the babble of the small brook that traveled beneath it among the mossy-green rocks. He had taken only a few steps more and paused. For the little path had ended, and he knew then something of the reason it had brought him here.

Ahead the woods opened to gentle hardwood hillsides painted red and gold, and between them little golden meadows grew. Beneath the little bridge, the tiny brook rushed along anew, happy to be there, flowing out of the woods – and on and on, to water the little gold meadows so that the earth beside them breathed soft and sweet. As far as he could see stretched the beautiful little hills and meadows, and between them lay broken thickets of popple, gray dogwood and alder. Upon all the sun was shining brightly, more brightly than ever he had known.

He was so taken that he did not see, at first, the old man standing to his side.

The man was older, it seemed, than even the hills, his face weathered by seasons and centuries, etched deeply as rock by the chisels of time. He was dressed in vintage hunting clothes, his hair and mustache long and white under a battered old felt hat. He was in waistcoat and jacket, a tie knotted at the collar, knickers and leggings, and tall leather boots, laced to the knee. Tattered, scuffed and torn to rags from the hunts of the ages. Across the crook of his arm lay an antique fowling piece, and about his shoulder an ancient game bag and powder horn.

But it was the small spaniel at the old man’s feet that most demanded his attention. She was in the bloom of her prime, sleek and muscled under a shiny black coat…as once Sally had been. Dancing and cavorting, she bounced up and down at the old man’s leg, begging to be on, until he mildly cautioned her to “Hup.” There she wriggled, tail beating, locked to him with beseeching eyes.

“Where is this place,” he asked the old man. “How did I come here?”

“It is not how, but why,” the old man said.

Puzzled, he was silent, uncertain what next to say.

“You have wished, I am told,” the old man continued. “I had the same wish, a long, many years ago.”

“I do not understand,” he said.

“You have a dog?” the old man said.

“Sally…” he said hesitantly.

“She is old. You wish to return to her your years.”

He understood now. “I have wished it were possible,” he said softly.

“Did you mean it?” the old man said.

The thought was incredulous, yet the old man did not quaver. For a moment he saw Sally, looking up at him, like the spaniel at the old man’s feet.

“Yes,” he said. “I meant it.”

“Then I have been sent to grant it,” the old man replied.

“But that cannot be?” he told the old man directly.

“Should you wish to quibble,” the man replied, “I will be about my way.”

He was dumbfounded, knew nothing to say.

“The years of your life,” the old man offered, “how many do you wish to give her?”

He stared at the old man, disbelieving. But, again, he did not waver.

“This is Molly,” the old man said, nodding to the spaniel at his feet. “I gave her ten years, in the Year of Our Lord, 1857. She was 16, I was 36. She lived and hunted with me in flesh for 11 more years. I died unexpectedly, I am told, at forty-nine. My father had lived to seventy.

“But I am very old now. Time is of no meaning here. But age travels on. That is a portion of the price. Only the dogs are ageless, so they are ever with us. Here, they live forever, doing the thing we love most.”

“This place, this beautiful place…” he said.

“It meanders on forever,” the old man said. “There are many of us here. Many of us as yourself, who had the wish. But only those who were willing to accept the sacrifice,” the old man cautioned. “You must decide, now or never,” he said again, “the years you will give.”

“Why did you not come earlier?” he said. “When I was younger…there were other dogs…I loved them all.”

“You have never wished so hard before,” the old man said. “It can be granted only once. I will say no more. Now you must decide, quickly.” The old man looked at the anxious spaniel. “We must be on about our hunt.”

He had thought about it many times. “I will give her seven years,” he said. The old man shook his head, “I am sorry my friend, but you do not have seven to give.” He could feel his body tighten with the weight of the old man’s words.

“You mean, my time is…”

“Yes…” the old man said sadly.

“Then…?”

“Six,” the old man said.

“Then I will give her three,” he said without hesitation.

“So it shall be,” the old man said, releasing the spaniel, turning away with no further word and never a look behind.

He had watched them out of sight, the spaniel happily ahead, darting merrily about the little golden meadows and the gentle, painted hillsides. Dancing in and out of the alders along the little gurgling creek.

Surely he must have slept then, for he was greatly at peace.

Many winters later Sarah Logan rocked in the old Shaker chair; before a fire, on a night much the same, deep in December. Once again aware of the rain on the roof, and of the wind, growing at the eves. Pulling off her glasses, she wiped the tears from her eyes, gently closing the yellowing pages of the family Bible and sinking against the back of the chair.

It was all there, the folks and the years. The blood of her blood and the flesh of her being.

All the many stories. At the ebb of his life, her grandfather had had a spaniel…Sally. They had died in the same month, after Christmas, in December. The year was 1954.

Her mother had told her of it many times. Something of a curious night, three years before he had passed. The spaniel was very old, had lived beyond her time. But strangely – to the last, even as her father was weakening – the spaniel acted almost as a puppy, had never faltered.

They had hunted together until the end.

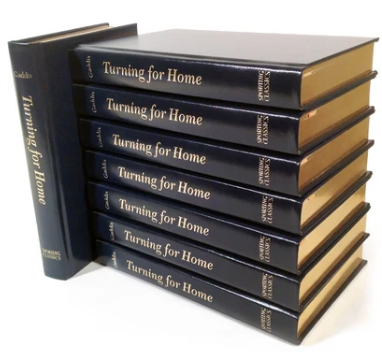

“The Gift” is one of 48 essays and 19 stories in his book Turning for Home. Here, in a new and eclectic compilation of masterful stories and essays, one of the most revered sporting authors of our time contemplates the homecomings of the sportsman’s heart. He unearths a treasury of broadly divergent encounters, from the delightfully absurd hilarity of Love Gloves,” to the piercingly intense melancholy of A Prayer from Dark Timber.” Each is told with an insight and dexterity that rarely gains expression, and each is drawn from the timeless and beloved pathways of the sporting life that wander between a laugh and a tear.

There is a juncture in every journey when your heart must find soon again something long, dear, and gently known. There is a waver in the wildest of wanderlust when the soul runs dry and must come again to the thing, the place, or the somebody that can make it replete. There is to every life an awakening that the miles ahead are greatly less than the ones behind, that beyond all things lies an end that you must come again as closely as you can to where you begin. Buy Now