Once he strikes a trail, a great rabbit dog like The General might just keep a’goin…on and on to the damn ends of God’s green earth.

Everybody in the piedmont had heard of the General, but nobody had hunted with him. His owner, Reverend Eddie Chapman, had become somewhat of a recluse. He had inherited some money and about half of the big old Chapman farm down near the river out between Spartanburg and Rock Hill, and he’d let the place go to pieces while he followed one hair-brain notion after another. Well, you can do no better for the rabbit population than to let a farm go to rack and ruin.

So the rabbits and the rabbit hunts in that region became, well, damn near epic. Especially if you threw the General into the mix. Only problem was nobody I’d ever talked to had ever been out there to hunt. They’d just heard stories about it.

Now all of us boys are sitting around Doug’s, the local meat and three, eating eggs and bacon before we head out deer hunting. Our waitress, a woman name of Rodena, tells us that a man named Haas two tables over has been rabbit hunting there with Reverend Eddie Chapman and the General.

So we invite this Haas to come over to our table and tell us about his hunt.

“Tell him we’ll pay his tab,” John Mitchel says to Rodena.

So this Haas raises his cup to us to say he’s coming. Then he gets a refill and comes over and sits down. And this is the story he tells us.

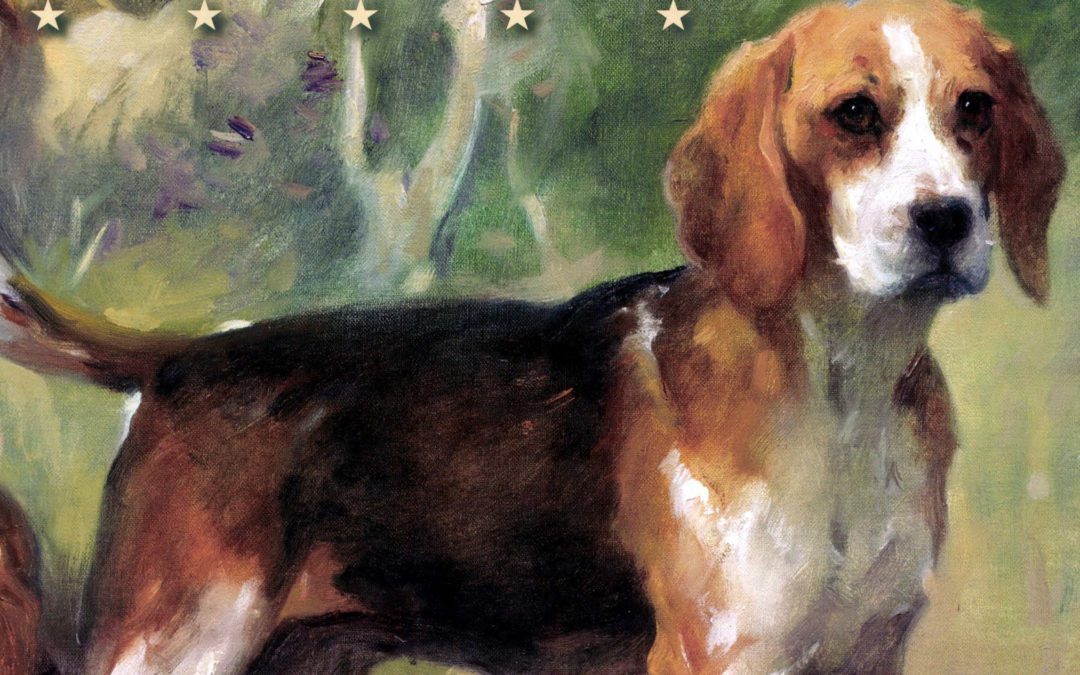

The General looked nothing like I’d thought he might look, boys. In fact, after the Reverend Chapman pointed him out to me, I had trouble distinguishing him from the other hounds we took hunting that day. Just another short-legged, long-eared beagle.

So I’m thinking: This is the dog I been hearing about since I came to town. Nothing particular ’bout him.

Well Chapman, who is a short, stubby fat man, directs the dogs down in the hollow near one of those fields that he’s let grow up in weeds, and they begin to sniff out the area around the creek, getting into some of those cut banks where there are hiding places. Suddenly, the dogs are onto something. It’s then that I understand why they call him the General.

He’s the dog that makes the announcement and heads up the troops. And if any dog gets in his space, why he growls in this low, mean voice like he means to give one warning and one warning only.

“Grhhhhhhhhhhh,” he says. Then he sucks in a little air – making this “ugh” sound – before you hear it again: “Grhhhhhhhhh.”

Well, the other dogs are true believers. They just give him room and look away, showing the whites of their eyes and tucking their tails as if they don’t even want to think about what might happen if they were to get him riled up.

Then, when they hit paydirt, the sound of his voice is like a bugle call, only no bugle I’ve ever heard has anything like outrage and joy in it, all at the same time. And this dog’s voice does. He’s found the villain, the offender – yep he’s found the prize. And everybody had better just fall in line cause the chase is on, and he’s the General, leading the troops.

Chapman and I are standing up the hill from where the chase starts and the rabbit darts right out in front of us close enough for a shot, but the Reverend just watches, sort of shaking his head as if to say, “Whoa, and don’t he run though.”

At first I think he’s crazy or slow – you never know about preachers – and then I realize he just wants to enjoy the chase, take his time, listen to the dogs.

After we listen for a moment or two to the music of six or seven beagles on the trail yapping and bellowing, Chapman casts his head to the side and closes his eyes.

“Hear that?” he says, shaking his head from side to side. “That high-pitched kind of wail a pitch or two above everyone else?”

I nod.

“Well, there he is – that there’s the Gen’ral.”

He looks around at me, shifting his gun to his left hand so he can use his right to pull up his sagging pants.

“Ain’t he sompthin’? The Lord made only the one. That’s all,” he says, holding up a chubby finger.

Chapman knows just about where the rabbit’ll reappear, so he puts me up the hill a-ways, and he takes the low area down close to the creek. We hear the wails and the bellows get soft and then they get a bit louder back over our shoulders as the rabbit does his circle and begins to head back to home turf. Then the Reverend takes that little double-barrel twenty of his and sights down it just to be sure all is right with it.

Then here comes the rabbit. I am unsure of the etiquette, but since I’m the guest, I figure I get the first shot cause the rabbit is coming about midway between us. Before I can even aim, I have moved around too much and the rabbit sees me, swerves and heads more in the direction of the Reverend.

I hear the pop of the 20-gauge, and the rabbit does a flip and falls dead between us. And then the dogs – here they are piling in all in an uproar cause of the shot.

The General is clearly the retriever. He’s on that rabbit in snapping-finger time, shaking him here and there a bit before the Reverend says, as if he’s talking to a person, “Now Gen’ral, that’s just about enough.”

At that, the General drops the rabbit and stands there panting with the other dogs. The Reverend holds the rabbit up for the other dogs to sniff and examine. He’s a well-fed bunny – ain’t no doubt about it. But we aren’t there to play or to congratulate ourselves. The Reverend gives the order, and the General and the other dogs are at it again.

After we bag two more rabbits in just about the manner we bagged that first one – me killing one and the Reverend one more – the General strikes an enormous cane-cutter. By now we’re closer to the river, hunting in the Johnson grass along the far edge of a fallow field that’s separated from the water by a thin line of sweet gums and cane in a swampy bit of land.

That old rabbit comes out of the grass kicking up dirt with his big back legs, and you can hear in the General’s voice a note of damn near panic. It’s as if they have just now started the real hunting – those first three were just for grins. He’s found the rabbit that set the world off balance.

“I be dog,” the Reverend says. “Don’t see that many a them, particular ones that big.” Then he lets go with a chortle. “Boy, we in for a tussle. That there’s a thoroughbred.”

This is the first time in the hunt that I have seen the Reverend strategize. Part of the problem is the grass and cane that grow in that swampy land along the river. “That rabbit get in there,” says the Reverend, “you won’t be able to smoke him out. And them dogs get all hung up in the mud. Might lose the scent.”

He shakes his head and looks at the sky. Then he just listens to the wailing of the beagles for a minute or two. Thinking.

“And you know what’s the truth ’bout a rabbit dog like the Gen’ral. He get on a trail a one he can’t catch or slow down, he might just keep goin’…on and on and on to the damn ends of God’s green earth, never to be seen by human eyes again.”

Then more thinking.

“All right,” he says finally. “There’s just one thing to do here.”

He places me on one edge of the swampland while he goes up and gets down in the grass itself. He seems to think that the rabbit’ll seek the grass.

It’s a while before the rabbit comes around, and he’s leading the dogs on quite a chase, but Reverend has us positioned perfectly. It prevents the rabbit from getting in the thick grass and disappearing. But the damn rabbit is so fast that he just smokes by us like a runaway train from hell before anybody gets a shot.

And then by the second circuit, I can tell that the dogs’ll soon be getting tired. They’ve already run down three rabbits, and this big old swamp rabbit looks as if he still has a marathon or two in him. Like he’s just enjoying the hell out of this. Like he was born to it.

So when I hear him coming a third time, I hatch a plan of my own. I decide I’ll move him toward the river and box him in.

And then the unexpected.

Apparently, the rabbit has done a switchback to fool the dogs, but it doesn’t work. And when they round the bend ahead of me, the General is about 20 feet behind him and the other dogs about 10 to 15 yards back from the General. The General’s barking and yapping has become one continuous, anguished yawp as he pushes his short legs as fast as they’ll go so he can get closer and closer to the varmint.

And then the damn rabbit disappears. Now I know he didn’t really disappear, but what I’m telling you’s this. I’m looking right at him coming along, and he turns or jumps or gyrates so fast that I don’t see where he goes.

Well there’s mass confusion among the dogs cause they don’t see where he’s gone either, and they’re dead tired to boot and can’t seem to follow the scent. And it’s then that I notice that the General has gone. I assume he’s still chasing the rabbit, but for some reason, he’s silent. Maybe he didn’t want the other dogs homing in on his prize rabbit or maybe he’s just as stumped as they are, but with his reputation and all, he has more on the line than they do.

Without their leader, the other dogs splinter and wander off in several directions, panting like they’re gonna die. But they come back pretty quick because they don’t seem to find anything.

I look up at the Reverend and shrug my shoulders. He does the same back to me. We scan the woods and cane and the Johnson grass, but it’s as if both dog and rabbit have been transported by damn magic out of the vicinity.

The silence probably lasts only about five minutes, but on a rabbit hunt in the midst of a chase with a dog like the General, that’s a damn long time. Eerie too. The silence I mean.

Then from out of nowhere I see something coming through that damn Johnson grass between me and the Reverend. It’s real hard to see, but the dried-out seedpods on the top of the grass go to trembling. And suddenly it’s as if the General has been restored to life on the spot by God Almighty.

His wailing begins in mid-wail, and the sound seems to go into the stratosphere, hitting notes that I bet the General nor any other beagle has never hit before. And here they’re both coming right at me, cause the rabbit has seen the Reverend in the Johnson grass.

“There he is,” screams the Reverend.

I break the rules a bit and step directly in front of the rabbit and draw a bead on him, but the damn General is so close, I’m afraid to shoot. So I move toward the river, which causes the rabbit to move even closer to the river.

Well unbeknownst to me, the Reverend has come up behind me even closer to the river, so that when the rabbit seeks to return to the canebrake and Johnson grass, he’s got the Reverend to contend with. And then the rabbit does something I ain’t never seen a rabbit do before. He disappears again, switching around here and there. And the next thing I know he’s heading for the river. And then he soars off into the river like some sort of winged creature out of a damn dream.

No, I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes. But I ain’t lying. It happened. And he hits the river like a water spaniel. And I can still see him such a remarkable sight it was…that head bobbing in the water, those ears plastered back as if in a pompadour, and him swimming and making good time like a damn otter.

And then I see the General jump in after him – only he don’t look nearly so spry as that old rabbit. He hits the water with a loud splash almost like a rock. And there the two of them are, swimming the dang river right at the swift part.

“By damn,” I hear the Reverend say behind me. “Sweet Jesus,” he says again, louder this time. “Shitfire!”

By now, the other dogs have hit the shoreline and are bunching up and yelping and howling like a bunch of banshees. They pace the shore and whine, but nobody is willing to enter the water. I guess that’s why he’s the General and they’re not.

For the second time I draw a bead on that damn canebrake rascal, but just before I pull the trigger, I feel the Reverend’s hand on my arm.

“Uh-uh,” he mutters right in my ear, “ain’t no way to retrieve him. We only kill what we eat on this farm. It’s the Lord’s way.”

Well, by the time the rabbit makes it to the other side and skedaddles up the bank and shakes himself good, the General’s a quarter mile downstream caught in the current. There’s been lots of rain and the river is high and fast. Suddenly, I see that the General is struggling, and then I see his head bob a couple of times.

“He’ll come up,” the Reverend says, all confident-like. “Just give him a minute. No rabbit can beat him, not even a canebrake varmint like that ‘en.” But I see on his face that he’s worried.

And then when we still don’t see the General break the surface, we walk upstream to look for him. But though we search up-shore and down, we don’t find hide nor hair of that General. Though we stay late into the night, building a signal fire for him and calling his name again and again, though the Reverend prays to the Lord, the General does not come.

His story finished, Haas leans back in his chair and holds his cup up to the waitress, signaling for more coffee.

For a few moments everyone’s quiet, thinking about swimming swamp rabbits and drowning dogs and cussing preachers and Johnson grass and all.

So old John Mitchel pipes up and says, “Richard Haas, is this here story true?”

“You accusin’ me a lying?”

“Well, no, but…we don’t know, never have known that the damn dog exists – or at least existed – and now you’re telling us that he don’t, but that he did and that he mighta died swimmin’ after a rabbit that was swimmin’ like a damn otter. Well…”

Old John Mitchel shakes his head as if he can’t quite figure out what else to say about what he has just heard.

Haas looks around at all of us as if we’re ungrateful wretches or traitors or even nonbelievers.

“If you don’t believe me,” he says, “you go find the General.”

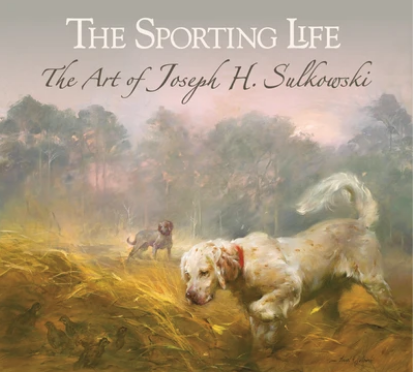

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski.

Acclaimed as one of America’s premier dog and sporting artists, Sulkowski shares his personal conversation with the outdoor life in a style of Poetic Realism. Influenced and guided by the hands of the Old Masters, he creates fluid brushstrokes that imbue his canvases with a compelling blend of light, atmosphere, and spatial effects that bring his passion for the sporting life into vivid focus for the viewer.

Whether it’s still-lifes, dog paintings or scenes of hunters and anglers, Joseph Sulkowski derives his inspiration from personal contact with the natural world. He carries out his visions through a lifelong discipline to his craft in which hand-ground paints, carefully prepared oils and varnishes, and handcrafted linen canvases and gessoed panels play a vital role in the quality of each work of art. Buy Now