We were camped on the edge of Pom Pom Lagoon in the game-filled Matsebe concession, located deep in northern Botswana’s 4,000-square-mile Okavango Delta. Here, brush-covered islands, mopane sand and big herds of buffalo, primary prey of the area’s magnificent lions.

The year was 1982, and Dave Harshbarger was on his first African safari with his good friend and California business associate, Steve Colwell. Accompanying the California hunting buddies were Soren Lindstrom and myself — Dave would be hunting with Soren, while Steve hunted with me. At the time, Soren and I worked for the Maun-based outfitter, Safari South, whose roster of respected professional hunters included Harry Selby, Tony Henley, Lionel Palmer, Simon Paul, Steve Liversedge and Dougie Wright.

After careful consideration Dave and Steve had chosen Botswana for a three-week general bag safari because of the variety of terrain and the sheer abundance of game. Buffalo topped Dave and Steve’s want-list, which also included kudu, warthog, zebra and gemsbok. Both of the Californians were keen wingshooters and they looked forward to sampling some of Botswana’s excellent bird-hunting. Dave was especially interested in taking a big-maned lion. About a week into the 21-day safari, Soren and Dave were cruising the islands and floodplains of the Okavango with lions in mind. It was late in the afternoon, and they were about to turn toward camp when they rounded a point of bush. Lying on a termite mound was a big lion and four lionesses, all intent on watching a herd of wildebeest. At the sight of the vehicle, the lion stood up and trotted across the grassy plain toward an island of brush.

“He’s a good one,” Soren said, knowing if the lion ran, it would be a risky shot for his client. But Dave had proven to be a capable marksman, taking several head of game with single, well-placed bullets. Soren felt certain that Dave could do it, but they had to act quickly.

Dave jumped from the vehicle, brought up his rifle and found the lion clearly visible in the 3×9 variable scope. The lion stopped at 75 yards and looked back at the hunters. He then began to lope toward cover.

The hunters could only inch their way through the dense tangle, giving the wounded lion a huge advantage.

Swinging his 375 H&H rifle slightly ahead of the bounding cat, Dave felt confident with the Sight picture and squeezed the trigger. The crack of the rifle shot echoed across the plain, followed by the solid thump of the bullet. Before Dave could shoot again the lion had melted into the long grass.

“It sounded like a hit,” Soren said, “but I can’t be sure. I saw no reaction.”

Dave got back in the vehicle, and the men drove up to the spot where the lion had disappeared. With rifles in hand, the two hunters and their trackers climbed out to examine the tracks. Squinting against the glare of the sun, Soren studied the deep, dish-size depressions in the sand. Small, crimson splatters of blood confirmed a hit. But the blood sign was meager, suggesting the lion probably sustained a less-than-lethal wound. Even so, once an animal is wounded, particularly a dangerous one, it’s up to the hunter to finish it, no matter how sticky the situation gets.

“Where do you think the lion was hit?” Soren asked Joseph, his head tracker.

“I don’t know. He didn’t jump or growl after the shot. It’s not good,” the tracker observed grimly.

Soren’s grip tightened on his 458 double rifle at the thought of a wounded lion hiding in the thick bush only a few yards away. His thumb automatically felt for the safety catch, and he pushed it to the off position as he knelt and peered into the shadows. He looked for a shape or movement in the dense undergrowth. He knew that tracking the lion across the sandy ground would be relatively easy, but he also knew that what lay at the end of the tracks would be nerve-wracking, gut-wrenching work.

The lion had escaped into the thickest part of the island, heading straight into the setting sun. Soren explained that it would be almost suicidal to follow the cat into the thick tangle, particularly with the sun’s bright glare in their eyes. They circled the island, checking for tracks, but found none.

“If the lion remains in this island of bush tonight, we’ll find him tomorrow,” Soren said, attempting to reassure Dave.

What Soren didn’t say was that Dave might also get a chance to see firsthand why the Botswana lion’s reputation is so fierce over the past 20 years the country has experienced more incidents of man-eating lions than any other African nation. Most of the attacks have occurred in game parks and reserves where wildlife is protected, but owing to the constant presence of people, many animals, including lions, have shed their fear of man. Lions and hyenas are opportunists and occasionally regard people as prey. The parks and reserves are not fenced, and the big predators roam in and out of the areas freely.

Soren studied the surrounding bush to get a lay of the land before darkness finally veiled the African landscape. Switching on the Landcruiser’s headlights, he turned the vehicle around and headed toward camp.

Earlier in the day Steve had taken a good buffalo and he was ready to celebrate his success when Soren and Dave rolled into camp. When they walked up to the campfire, their faces reflected a somber mood, which soon permeated the camp atmosphere.

Dinner was strangely quiet that evening. Dave couldn’t erase from his thoughts the sight of the running lion and his shot at him before the cat disappeared into tallgrass. After dinner we sat by the fire and discussed our strategy for finding the lion. It was a job that nobody liked, but Soren and I agreed that it would be best to team up. Both of us, along with our trackers, had followed wounded lions before, and we knew that when pressed, the lion would most likely come for us.

We also knew that tracking the wounded lion with more than two guns along could complicate matters, sometimes tragically so. Fresh in our minds was the case of Henry Poolman, a professional hunter from Kenya who was accidentally shot and killed by a tracker when Pool man stepped between a charging lion and his client. I knew from a couple of my own close calls with charging lions that whatever happened, it would happen fast.

We decided to position Dave and Steve and my tracker Sanga in trees where they would have a degree of safety, but more importantly, the advantage of height would help them spot the lion if he moved away from us and came in their direction. They might even get a shot at him. Meanwhile, Soren and I, accompanied by the other three trackers, would track the lion on foot. Our team included my number-one tracker, Galabone, (pronounced Ha-Ia-boney) and both of Soren’s trackers, Joseph and Kelibile (pronounced Kill-a-bee-lee), all experienced and well familiar with dangers in the bush. We would leave after breakfast.

Arriving at the brush-choked island the next morning, Soren pointed to where the wounded lion had escaped. We circled the island to check again for his tracks and found none. We were pretty certain he was still hiding somewhere within the dense bush. At the opposite end of the island we positioned Dave, Steve and Sanga in trees that offered commanding views of the area.

I left my Land Cruiser parked nearby and climbed into Soren’s vehicle, then we drove about a half-mile back to the other end of the island. After discussing the situation with our trackers, it was agreed that Galabone and Joseph would work side-by-side, scanning the ground for tracks while Soren, Kelibile and I would keep watch for the lion in the bush ahead.

My custom bolt-action Mauser was chambered for.458 Win. Mag., which was capable of dropping a charging elephant. It was fitted with express sights and stoked with factory Winchester loads pushing a 510-grain, soft-nosed bullet at slightly more than 2000 feet-per-second. Together, our two 458 rifles could unleash more than five foot-tons of energy — a massive amount of knockdown power if directed to the right spot.

Taking up the lion’s tracks locked us in a deadly game of hide-and-seek We moved slowly and deliberately willie Galabone and Joseph bird-dogged the tracks, while our eyes looked through, around, over and behind every bush, tree, termite mound and fallen log. It was tedious and tiresome work, without an ounce of joy to it. Inching forward on hands and knees, we wiped sweat from our eyes to peer into thick foliage that we parted with our rifle barrels. Tension gripped us like the clenches of a coiled snake, and each of us could heat “the breathing of the others as we moved toward an invisible quarry. Like the silent support of a friend, my rifle’s familiar feel was reassuring.

An hour of painstakingly slow progress brought us to an area where the grass was matted and spotted by dark, dry bloodstains. Here the lion had lain in four or five places during the night. Blood sign had decreased gradually, and there was little to suggest he was weakening from his wound. Tracking became more difficult with less blood to follow, and moving through thick bush we were often forced to split up and cast about to locate the tracks.

Spending an extended amount of time in a state of condition-red eventually took its toll. After three hours our concentration began to lag, and ironically, fatigue from stress triggered an impatience that actually caused us to quicken our pace. In a subconscious call for confrontation, we pushed forward, almost daring the lion to charge, or run, or at least growl.

We were tired and frustrated, and our state of mind shouted for something to happen. But this would come at a cost — our actions unwittingly pushed the pendulum of advantage to the lion’s side.

Lions are superb hunters who bring down large prey by instinctively knowing the best time to launch their attack. That same instinct works for them in defensive situations. Armed with large, bone-crushing teeth and claws that grab like steel hooks, the lion is one of the most formidable game animals on earth. Add to that mix a poorly placed shot, and you have all the ingredients that can spell disaster for the hunter.

Our battle would begin at the lion’s choosing — when we were least ready and our guard was down. While the rest of us looked for tracks on the ground, Kelibile spotted the lion first. The tracker, with a minimum of movement, quietly reached for my arm and pointed a stubby finger at the thick undergrowth 50 feet away. I followed the direction of his finger to see two yellow eyes blazing with anger.

The instant the lion locked eyes with us, he began lashing his tail, signaling his intention to charge. With the trackers behind us, Soren and I concentrated on the ball of fury in front of us. The lion’s lip curled back, revealing long sharp teeth, and a deep angry growl ripped the still air.

The enraged lion charged in a quick rush, but somehow the world shifted into that slow-motion state that’s often described by those in life-threatening situations. In two bounds he was only a few yards away. Soren, a fine shot and quick to reflex, fired first.

Staring in disbelief as the animal kept coming, I shot with the beast only a few feet off the end of my barrel. Slowed only slightly, he kept coming.

We were trapped in a living nightmare with a deadly lion, and it felt like we were defending our lives with cap guns. I remember thinking his monster must be bulletproof, and wondered how we’d end the madness before someone was bitten. I wasn’t long to wonder.

The lion knocked Soren to the ground like a rag doll and ran over the top of him, brushing by me so close that I could have touched his back with my hand. Even if our shots had missed, I could only imagine that two rifle blasts in his face must have shocked or confused the big cat, for by all lights he should have pressed his attack on Soren or me.

Before I fully registered what had just happened , a blood-chilling scream came from behind me, and I turned to look in horror at thelion ‘s rear end as he began mauling one of the trackers . Hunched over his victim , he shook with the effort, much like a terrier shaking a rat. As I bolted a fresh round into my rifle, the screams from underneath thelion stopped as suddenly as they had started.

I could not shoot from where I stood, for fear of hitting whoever was under the lion, so I moved forward with the intention of placing the barrel in the lion’s ear and blowing his head off. But before I had taken three steps, the lion abandoned his victim, moving directly away from me. I snapped off a shot at his rear end before he was swallowed by thick bush, and then ran to the tracker, fearing the worst.

The bloodied body was face down and lay motionless in the sand. Thelion continued growling nearby, and Soren rushed up beside me to keep us covered in case the lion charged again. I carefully turned over the prostrate body, and winced in shock at the Sight of Galabone’s expressionless face. The top of his head was badly gashed, and blood from deep claw wounds seeped through his ripped and torn green overalls in several places.

When I felt for a pulse in Galabone’s neck his eyelids began to flutter, and I silently thanked God he was still alive. When the lion finally stopped growling, Soren knelt down to help me check Galabone’s wounds to be sure there were no arteries severed or bones broken. Miraculously, everything seemed to be intact. Joseph and Kelibile materialized beside us and helped lift Galabone to his feet and shuffle him over to my vehicle several hundred yards away.

Dave and Steve, surprised by the shots, were even more shocked by the screams and roars they’d heard. They had maintained their tree-borne vigilance until we shouted for them to climb down, and then had came running to look on in horror as we limped in with the bloodied tracker.

We immediately broke out the first aid kit, then set up the radio to call for a mercy flight. We irrigated Galabone’s wounds with a syringe of strong antiseptic wash and got him to swallow a handful of painkillers and antibiotics. Still silent, he began shaking uncontrollably from shock and we wrapped him in a blanket. Within a couple of hours of our call for help Galabone had been picked up by an aircraft at a nearby bush airstrip and was under a doctor’s care at the Maun Hospital.

We then requested that our safari headquarters in Maun leave the radio on with someone monitoring it, for we still had to deal with the wounded lion.

We now recognized that whatever the extent of the lion’s wounds, they were only serving to anger him. Short of administering a paralyzing shot to the brain or spine, we were sure to face another furious charge.

We formed another plan and regrouped by putting Dave and me and the three trackers in the back of Soren’s Landcruiser. Soren drove with Steve next to him, both cradling their rifles. Even though our nerves were frayed and raw, we headed back into the bush to face the lion once again. Soren pushed and crunched his Landcruiser through a thicket of bush, trees and vines to where we had last heard the lion. Dave and I held onto the lurching vehicle with one hand and our rifles with the other.

When we could go no farther with the vehicle, we began scanning the brush and soon spotted a patch of tawny hide about 20 yards away. As we tried to make head from tail, thelion burst out of the bushes in a scene that’s seared in my mindlike a freeze-frame from a horror movie. His head was bloody, hismouth gaped open hideously, and his eyes bore straight through us. Dave fired just as the cat reached the front of the vehicle, and I fired a fraction of a second later.

Rearing up on his hind legs, the lion tried to claw his way onto the hood. Dave fired again and his bullet knocked the lion off the Land Cruiser. He was moving back into the brush when I fired a shot that dropped him. Dave shot again — the ninth round to be fired at the lion — and he fin ally lay still. He would not get up again.

Only after inspecting the lion were some of our questions answered. Upon his initial charge, one of our shots had ricocheted off a tooth and gone onto smash his lower jaw. The enamel on a lion’s tooth is hard enough to deflect a bullet, even one with 5,000 foot-pounds of energy behind it. This is why shooting a lion in the head is considered a risky shot.

Galabone had survived the bite tohis head because the lion’s jaw had been shattered. When the cat tried to bite him, he only gashed the top of Galabone’s scalp with his upper canines. It could also explain why thelion had left him so quickly.

When a lion attacks, he normally stays with his victim long enough to inflict serious injury or death. A wounded leopard, however, often dashes from person to person, biting as many as he can. Dazed, shocked and unable to bite properly, the lion left Galabone to seek the nearby security of the bush.

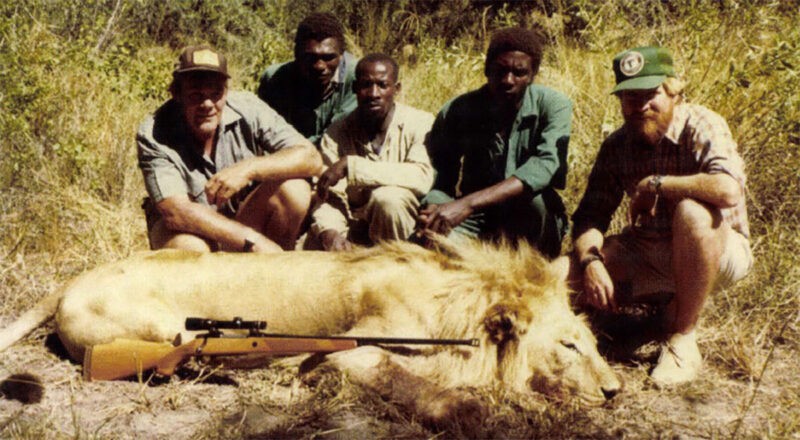

The author (far right), fellow PH Soren Lindstrom and their trackers with the lion that would not die.

The tracker spent a little less than three weeks in the Maun hospital and was released without further complications. Later, he told me the lion knew that Galabone was the one pointing out the tracks and that’s why he passed up Soren and me to attack him.

There is little love for lions among native Africans, who historically regard them as an evil menace. Plenty of superstition surrounds the big predators, and the safari crews always celebrated as if the devil himself had been killed whenever a lion was brought into camp. Some Kalahari bushmen believe that certain lions are capable of transforming themselves into human form. Those are the lions, they say, that you don’t want to mess with.

Galabone rejoined Sanga and me on safari a month later and completed the rest of the hunting season with us, showing no hesitation to track up a lion on foot. But he did say that the next time we had a wounded lion in thick bush, he would let someone else point out the tracks.

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now