I have been privileged, over the course of my life, to know a number of folks with sharp tongues, sharper wit, and a gift of rapid repartee that cut like a well-honed pocket knife. None of them, however, quite matched Britt McCracken.

The people of my native Smokies have always been noted for their humor – sometimes wry, often eccentric, and invariably distinctive. I have been privileged, over the course of my life, to know a number of folks with sharp tongues, sharper wit, and a gift of rapid repartee that cut like a well-honed pocket knife. None of them, however, quite matched Britt McCracken. A friend of my parents, the father of a high school classmate, and a man whose company I enjoyed a good bit as a youngster, Britt was one of those jolly souls who somehow consistently managed to wring every bit of the juice of joy from life’s sponge. He stands in a class by himself as the funniest man I have ever known.

Mentally quick as a snake’s strike no matter what the subject at hand, Britt always seemed to wear a smile and be the quintessence of good nature. A nephew of legendary Smoky Mountain sportsman Mark Cathey, a man who was in his own right noted for pranks, Britt was likewise an avid hunter and fisherman who clearly inherited his uncle’s droll sense of humor.

Many, though by no means all, of the countless hilarious high points of his life revolved around outdoor experiences. When barely in his teens Britt was privileged to accompany his Uncle Mark and a bunch of other locals on a fox hunt. These outings primarily consisted of building a big fire atop some ridge where it was possible to hear at great distances, relaxing around that fire with ample liquid refreshment, telling whoppers and bragging on dogs.

On this particular occasion Mark allowed his nephew to lead a cherished hound by a leash and told him, once a fire site had been selected, to tie him off until it came time to release the dogs. Britt did just that, but thanks to involvement in other matters and perhaps a bit too much tanglefoot, his uncle failed to tell him to turn the hound loose. Accordingly, when the pack of dogs struck a trail and started sending a hallelujah chorus of hound music ringing through the hills and hollows, Uncle Mark’s favorite was still tied up. On multiple occasions Britt tried to interject and explain the situation, but each time he was abruptly shushed and reminded that youngsters were to be seen only a bit and not heard at all.

Thus, matters remained until Cathey began bragging about his dog leading the pack hot on the fox’s trail and offering comments to the effect of “Listen to him sing a song. He’s making life miserable for that fox.” Somehow Britt finally managed to convey the message to his uncle that the prized hound, far from leading the pack, was still tied up less than a hundred yards away. Cathey was then himself fit to be tied, and for once the prankster and storyteller was hoist on his own petard.

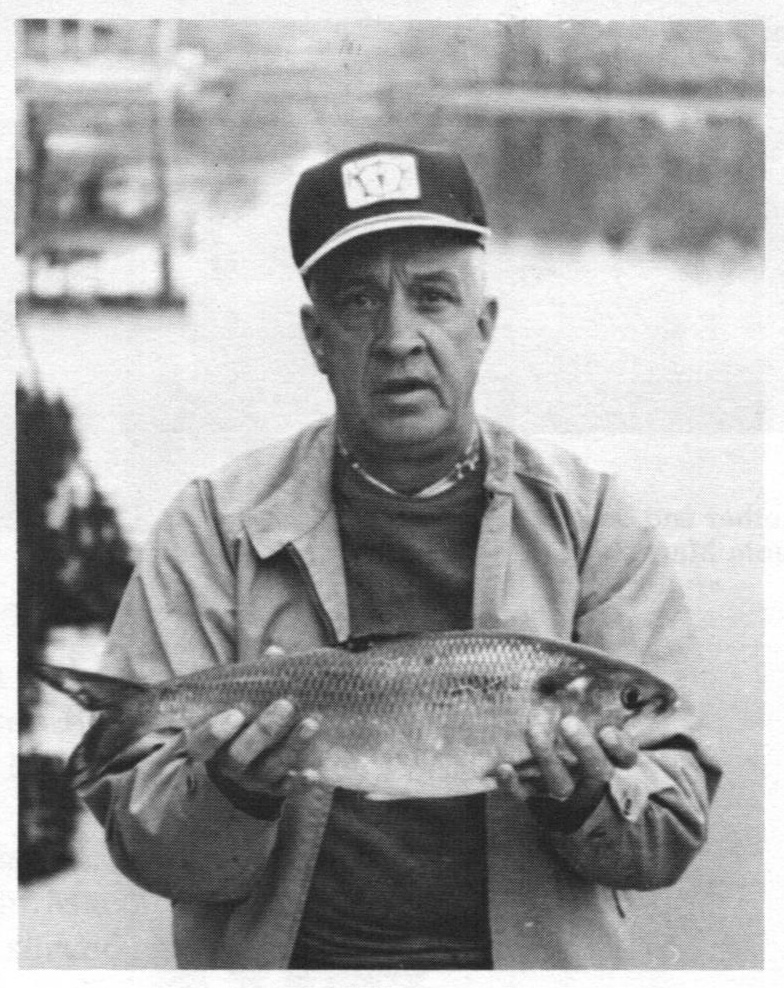

Britt McCracken shows off his catch of the day.

It was years later, however, when “Britta McCrack,” as his buddies often called him, came into his own as a man of merriment. On one occasion I happened to be an observer of a prime example of his humor. This came during a golf match where, as a caddy, I enjoyed a front row seat in a movable feast of comedy. He always kept folks in stitches, and this time he had three of the four golfers, along with a quartet of caddies, literally rolling on the ground. The sole exception was the “pro” and course manager at the local club.

The golfers had a modest wager on their match, and as they reached the 18th green Britt and his partner seemed destined to lose the bet. All the “pro” had to do was sink a short putt – less than three feet in length – to close the deal. A far better golfer than most local linksmen, the pro was a bright, likeable fellow who taught school and managed the golf course on the side. However, he did possess an exceptionally short fuse, and on this occasion, he exploded before the laughter of others in effect forced him to overcome his wrath.

It all came about when, just as he struck what seemed sure to be the match-winning putt, Britt broke wind in a fashion fit to shake leaves off nearby trees. The release could have come straight from Geoffrey Chaucer’s story of the miller in Canterbury Tales. The putt, far from being holed, ended up all the way across the green. The pro and his partner lost the match, and it was a full 10 minutes before matters returned to even a semblance of normalcy.

Juvenile? Unquestionably. Yet there was no denying Britt’s impeccable sense of timing or the plausibility of the explanation he offered by way of a supposed apology. With a perfectly straight face he stated: “I long ago learned that it’s better to fart and bear the shame than hold it in and feel the pain.”

On another occasion, at some point in the late 1940s or early 1950s and not too long after returning home from service in the U. S. Army in World War II, Britt held a job driving a bus which made daily runs between two mountain towns. The route followed a steep, tortuous course along a two-lane road crossing lofty Soco Gap.

This particular day Britt had a full load of riders and was running a bit late. With a single exception, however, the riders were unconcerned. Most were local residents who realized Britt would make up time as best he could. If they failed to arrive precisely on schedule, so be it. They were living on what might be described as Smoky Mountain time rather than answering to some strict observance of a clock.

The one rider lacking that relaxed attitude regarding bus schedules was a prim, proper Yankee lady, dressed in Sunday go-to-meeting clothes, who graced the bus seat immediately behind the driver. Her accent and attitude left little doubt that she was an outlander of precisely the sort sure to set local nerves on edge. She began giving Britt a verbal ration of grief for running behind schedule even before boarding the bus, and it continued apace once she had taken her seat. She launched into a tirade condemning shoddy service and local indifference to the way things should be done, complaining almost non-stop as the bus, grinding away in “granny gear,” made a slow climb towards Soco Gap. She threatened to report the driver, contact her lawyer, and in general raised a ruckus.

To his credit Britt remained stoically silent. However, once he topped out over Soco and started down the mountain towards Cherokee, as was his custom when needing to make up time, he really let the old bus roll. That suited all his passengers except this vocal harridan just fine, but within a mile or two of Britt straightening the curves she had gone from criticizing his slow pace to alarmed comments about his excessive speed.

Finally, with more than a hint of fear in her voice, she said, “Driver, if you’ll stop this bus, I’ll get off.”

Britt had endured all he could, and in a masterful example of the perfect squelch, he replied in a gentle, soft-spoken, and seemingly dead serious voice, “Lady, if I could stop this bus we’d both get off.” Silence reigned supreme for the remainder of the trip down the mountain.

On another occasion Britt was fishing a trout stream in north Georgia which had been designated “artificial lures only.” Action was slow and after an hour or so he decided illegally tipping the Yellarhammer fly adorning his in-line spinner with a night crawler might help matters. When he did so, action picked up almost immediately. He creeled three of four trout in the span of a half hour, but then, happening to look downstream, he spotted a game warden headed his way on the streamside trail. Britt realized the situation demanded some immediate, drastic action.

It was too late to reel in and remove the night crawler, so he began jerking the spinner in violent fashion, figuring surely the illegal bait would be torn off. Alas, it was not to be. He had done too good a job threading the night crawler on his hook. When the warden stepped up to him, asking to see his license and check his lure, Britt took the only route that came to mind. He reeled in his spinner with the night crawler still attached and then shook his head in disbelief.

“I’ll be damned,” he said. “Over the years I’ve caught pretty much everything in the way of different species on a spinner. Once I even hooked and landed a hellbender, but this is the first time I’ve ever had a night crawler strike.” The bemused game warden was so tickled by his originality and seeming seriousness he let Britt off with a warning.

Then there was a time when he was part of a group camping on one of the streams running into Fontana Lake’s north shore. The campsite had a rough privy, and after supper the group had taken the easy but somewhat foolish expedient of dumping their scraps and leftovers, including the bones of a big mess of trout they had consumed, down the outhouse hole.

At some point well after dark, but when everyone was still sitting around the convivial campfire telling tales, one member of the party got up and headed for the john. At that juncture it’s best to pick up with Britt’s direct account. “The fellow got settled down to business and was making good progress,” Britt said, “when the ground beneath him began to rumble and the toilet seat commenced to shake.” It turns out a small bear, apparently attracted by the smell of the fish and other fried foods, had somehow managed to clamber down into the privy hole.

“I’ve seen sack races and three-legged races where folks managed to scramble along at a pretty good pace,” Britt related. “But let me tell you right now. You ain’t seen speed until you watch a guy with his britches and underwear around his ankles making tracks after a cheek to cheek encounter with a bear. How he kept from falling and half killing himself is a mystery to me, but I guarantee he set a new time record for a hobbled man fleeing from a bear that had just been pooped on. It also provided an immediate cure to any constipation he might have been suffering.”

In singularly delightful fashion James Britt McCracken was a comic genius, and these examples of his wit are but a slender sampling. To be around him was to laugh. He was that funny.

In A Smoky Mountain Boyhood, Casada pairs his gift for storytelling and his training as a historian to produce a highly readable memoir of mountain life in East Tennessee and western North Carolina. His stories evoke a strong sense of place and reflect richly on the traits that make the people of Southern Appalachia a unique American demographic. Casada discusses traditional folkways; hunting, growing, preparing, and eating wide varieties of food available in the mountain region; and the overall fabric of mountain life. Divided into four main sections—High Country Holiday Tales and Traditions; Seasons of the Smokies; Tools, Toys, and Boyhood Treasures; and Precious Memories—each part reflects on a unique and memorable coming-of-age in the Smokies. Buy Now

In A Smoky Mountain Boyhood, Casada pairs his gift for storytelling and his training as a historian to produce a highly readable memoir of mountain life in East Tennessee and western North Carolina. His stories evoke a strong sense of place and reflect richly on the traits that make the people of Southern Appalachia a unique American demographic. Casada discusses traditional folkways; hunting, growing, preparing, and eating wide varieties of food available in the mountain region; and the overall fabric of mountain life. Divided into four main sections—High Country Holiday Tales and Traditions; Seasons of the Smokies; Tools, Toys, and Boyhood Treasures; and Precious Memories—each part reflects on a unique and memorable coming-of-age in the Smokies. Buy Now