George was a legend to those at the Compleat Angler, and to catch and kill him would be an unspeakable villainy. Or would it?

I hope George is all right,” said Basil as he began on his beef.

“Right as ninepence, Selby,” said Major Poole, “and stouter than ever.”

“It hasn’t yet been definitely ascertained. But it’s generally agreed that he’s put on flesh since last season. Personally,” said the Major, “I think he must go quite the four and a quarter pounds now.”

“Not by two ounces,” snapped old Mr. Wellington. “Four two is his weight, or I’ll eat my brogues.”

“Who is George?” asked Arethusa Lyne. She sat between Basil (to whom she was affianced) and her mother. These three had descended at the Compleat Angler only ten minutes previously; dinner being on, they had come straight into the coffee room, where Basil had found several habitués go whom he was well known.

“George,” said Basil, ”is a trout that lives in a pool close by here. I’ll introduce you to him after dinner. He’s a famous fish, for I may tell you that a four-pounder in the Yeoman is simply fantastic. Anything over a pound here-abouts is an absolute whale. And at the end of last season George weighed precisely four pounds and one ounce. He’s known throughout Deveon and Somerset and there’s not a West Country angler of any repute who hasn’t had a go at him.”

“Can’t they catch him?”

“Some of them can. Not many. The place where he lies is as near as needs be impossible. It takes a broth of an angler to ensnare George, I promise you.” He paused.

“Selby is modestly waiting, Miss Lyne,” said Willie Rook, “for one of us to tell you that he, Selby, has had George out no less than three times. Permit me to give you this piece of information. Now Selby, you can carry on with your tale.”

“It is even so,” said Basil, “and that’s how I know what his weight was last September. Before putting him back —”

“Do you always put him back?” she asked.

“Always,” he said. “It’s an understood thing that anyone who catches George puts him back. It would never do to have George slain. He confers a luster upon this hotel that is absolutely unique. Anglers come from the United States and New Zealand just to fish for George. His fame is worldwide. He is legendary. To kill George would be a quite unspeakable villainy. I don’t believe that even a Norwegian farmer could be wicked enough to kill George. George is sacred.”

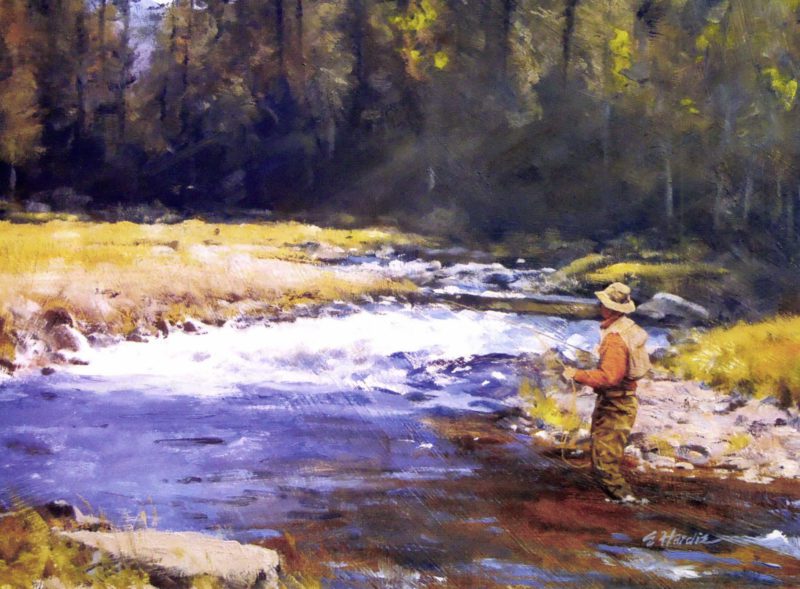

by Eldridge Hardie

“But,” she objected, “suppose some angler came along who didn’t know that George mustn’t be killed.”

“Oh,” he replied, “there’s a notice-board by the pool to say so. We had it put up five years ago; the people, I mean, who come here fishing. Besides, it’s unlikely that anyone who was man enough to catch George wouldn’t know about him. One would as soon expect a plus-four golfer never to have heard of St. Andrews.”

“He’s very hard to catch, is he?” she asked.

“Well,” he explained, “I wouldn’t say that. If you can get your fly to him properly, he’ll generally take it. We have a theory that George knows he won’t be killed, and that when he sees a fly properly presented to him, he says to himself: Now that’s a pretty good effort. This fellow deserves his reward … and thereupon he takes the fly, gives the angler a good run, and gets off or is netted as the case may be. George, in a word, is a thorough sportsman. I drink long life to him.” And Basil emptied his pot of ale.

“Well,” said Arethusa, “I call it pretty hard luck on the trout.”

“What do you mean ‘pretty hard luck on the trout?’” Basil cried. “I tell you George simply loves being caught. Doesn’t he, you fellows?” he demanded of the other fishermen. They all swore that to be caught was George’s greatest pleasure in life.

Arethusa didn’t argue the point. She was too hungry, and the beef was too good.

After dinner Basil led her, according to his promise, out of the hotel, across the road, through a gate and into a wood of young oaks, where they found the Yeoman making its way to the sea. Almost at once they stood by the pool where dwelt George, that inconceivable monster.

Bail showed Arethusa the notice-board which stood by the pool. It read: “Any angler who catches the large trout that lives in this pool is earnestly entreated to return him to the water.”

Then Basil pointed out the place where George habitually lay. A particular description of it, with diagrams and measurements to the eighth of an inch, would be out of place. I will only say that George’s lair was an exceedingly narrow passage, thickly overhung with hazel bushes, at the very head of the pool, and only to be entered by a fly that should be thrown from a point situated some 25 yards downstream, because, owing to the depth of the pool, it was impossible by wading to get any nearer; and that since the whole place was closely over-arched by the branches of trees, and thickly shrouded in undergrowth, the projection of a line 25 yards in length was a feat to tax the powers of the Apostle Peter himself.

Arethusa was duly impressed, and said that she didn’t think she would probably waste very much of her time angling for George. In the wood there was very little light, for the sun had been at least three hours gone out of the valley. George, therefore, on this occasion was not to be seen lying in the water. But even as they gazed at the place where he was supposed to be, there came floating upon the oily glide that floored the little green tunnel a pale insect which fluttered once and again.

And lo! An august snout emerged, followed by a broad olive-green back, and the fly was gone, and in the water there was a heavy swirl, while Basil said, “That’s him,” and Arethusa clutched Basil’s arm, and emitted an eldritch scream.

“Always the little gentleman, George is,” said Basil as they went back to the hotel. “He knew you wanted to have a look at him.”

“Oh Basil,” said the girl, “if ever I catch a trout like that I shall give up the ghost for sheer beatitude.” Hitherto the young lady had grassed nothing heavier than six ounces.

Basil squeezed her to reward her enthusiasm. “No, you won’t,” he said. “You’ll be too keen to go on living, so that you may catch a still bigger one. And now you’ll want to help your mother to unpack and get to bed.”

He kissed her good night and repaired to the bar to exchange fishing boasts with the Major and little Willie Rook and old Mr. Wellington and the rest of them.

by Eldridge Hardie

Nobody fished seriously for George; I mean, none of the habitués did. Ambitious strangers might set down behind the great trout and devote long hours or even whole days to the hopeless siege of him; but the habitués knew better. They were at the Complete Angler to catch fishes, not to lose their time and temper juggling a fly in and out among the leafy defenses of George.

After breakfast they distributed themselves over the various hotel waters — this man up the Yeoman, that man down the Yeoman, the next up the Cobley Brook, a fourth on the Davy in the next valley, a fifth on the Brewer two miles away.

When they fished for George, it was before breakfast or after tea or dinner. Anyone, in short, who had an empty half-hour on his hands was as likely as not to take his rod and go and attempt to put a fly over George’s nose. This feat was so difficult that it was never undertaken save apologetically and as a sort of joke. Very, very rarely, as we know, it was accomplished, and then George might be risen and missed, or perhaps hooked and lost, or actually brought to the net. But no one who went out to fish for him ever expected anything but failure.

On the third morning of her stay Arethusa came down to breakfast to find Basil just entering the hall with his rod in hand. “Well,” she said, “you’ve been at it early.”

“Yes,” he replied, as he put his rod up on its hooks. “I though I’d just see if I could land old George. I did, too,” he added casually.

“Basil!” she screamed. “How could you, and with me not there to see?”

“If you had been,” he told her, “you wouldn’t have seen it, because it wouldn’t have come off. George hates a gallery. He weighs four and a quarter pounds by the way. My balance says so, at any rate. Old Wellington is wrong, and I shall insist on him eating his brogues.”

Basil took it all very lightly, but it was obvious that he was thoroughly pleased with himself. And, indeed, to have taken George four times out of his pool was a very considerable thing to have done.

At breakfast Basil was quite the hero, but he didn’t succeed in making old Mr. Wellington eat his brogues; for old Mr. Wellington simply maintained that Basil must have read his balance wrongly.

Basil put on airs. He announced that he was never going to fish for George again. He’d had enough of catching George. George was altogether too easy, he said.

“Well,” said little Willy Rook, “I don’t fancy anyone else will catch him this summer. You’ll have given him a distaste for flies, Selby, that’ll last him for some time.”

But little Willie Rook was wrong. Before a week was out he himself had landed George. He, too, reported that George weighed four and a quarter pounds. Old Mr. Wellington, however, still declined to eat his brogues. This time he gave no reason for his refusal. He just refused — angrily.

It really looked as if Basil had been right and that George was a thorough sportsman. It looked as if he did positively enjoy having a tussle with an angler. Unless this was the case, it was almost incredible that a trout of George’s size and age should let himself be caught twice within ten days. Once a season is as much as such a fish’s nerves can ordinarily stand. But George was very far from being an ordinary trout. He was, when you come to think of it, more of a pet than anything else.

Arethusa was an honest, humble-minded young fisher-woman. She knew herself to be still a mere bungler, though she was quite tolerably pleased with the advance she had made since, during the previous summer, Basil had entered her at the game. She could catch trout in quite respectable numbers, given that conditions were strongly in her favor — that is to say, if the wind was upstream and the fish were hungry. A basket of half a dozen was nothing out of the way for Arethusa. But she knew her limitations; and she had recognized at once that she would do better not to aspire to the grassing of George.

And so, during her first fortnight at the Complete Angler, she was very well satisfied to fish, with Basil, the many miles of the hotel water in which George was not. During these days she covered herself with moderate glory, on two occasions wiping the eye of old Mr. Wellington to his extreme annoyance and the intense delight of all the other habitués.

On her 15th day, however, she and Basil having been on the lower Yeoman, she arrived at the hotel about half an hour before tea-time, and to kill this half-hour, went down to George’s pool just to have a look at him, a thing which she had done many times before.

There he lay in his little green tunnel: huge, solid, phenomenal, and almost motionless. To Arethusa, wholly inaccessible.

Oh, she thought, for the skill to put a fly only once over that great brute’s nose! And she cast a baleful eye upon the close-set greenery by which he was surrounded. “If this were only cleared away,” she murmured, “it would be grand.”

Suddenly her heart stopped beating, then bounded against her ribs. George had left his tunnel (a thing which he was supposed never to do) and had come down into the pool. Around it he now proceeded slowly to cruise. Arethusa knew that a marvelous, incredible opportunity had been presented to her, but she did not realize that George was simply behaving like the gentleman he was.

Suspending entirely the movements of her breathing apparatus, she detached from the cork handle of her rod a small red tag with which she had been fishing since lunch, and letting it and the cast swing clear, lowered her point and held the fly steady a foot above the surface.

As George came loafing along, Arethusa made the red tag dance, and George halted to gaze upwards. Arethusa lowered her point still further and the dry red tag just touched the surface. George — good sportsman that he was — hurled himself upon it and was fast.

A hundred thousand eons later Arethusa lifted him in her net from the water, laid him in the grass, and fell on her knees beside him.

Next moment George had got it in the medulla oblongata from the handle of the net — whack! He gave one strong shudder of approach and was still forever.

Then Arethusa came to herself. The red mists which had been obscuring her vision scattered and were gone, and all things became clear again. She knew what she had done.“Oh heavens!” she cried, leaping to her feet, “I’ve killed poor old George!”

She stood looking down upon the lovely corpse and was suddenly blinded by tears; three or four great sobs burst from her. The triumphant joy which should attend the slaughter of a four-and-a-quarter-pound trout was singularly to seek within her bosom. She felt much worse than Cain did just after he murdered Abel, for Cain was only scared; whereas Arethusa was filled with remorse as well, not to mention pity for poor, gentlemanly, sportsman-like George.

Crying never picked up any spilt milk, and Arethusa knew this perfectly well. She realized further that it behooved her to take speedy counsel with herself as to what she was to do. At any moment an habitué might be inspired to come down to George’s pool and have a go at its principal denizen. Suppose she should be found by a habitué standing red-handed above the corpse of George. Suppose the habitué in question should be Basil. She had left him busy on a fish only a few hundreds yards below the hotel. He was certainly not far away. Suppose she should now see him coming toward her through the oaks!

Panic laid hold of her and, tearing up some double handfuls of green stuff, she scattered them over George’s body. Then, with the spike in the butt of her rod, she began to dig in the clay of the bank. The clay was as stiff as soap and very soon she broke a nail. But she persisted and presently the little grave was prepared. She dropped George’s body into the hiding place, scrabbled the clay on top of him, trod it flat with her brogues, and then scattered the greenery over it. Then she whispered: “An otter has killed George. Yes, an otter did it.”

She waded into the Yeoman, cleaned her brogues, cleaned her hands, took her rod, and began to move in the direction of the hotel. But at the edge of the wood she paused and looked back…

Note: William Caine was best known in the fishing world for his 1911 book, An Angler at Large. “The Four-Pounder” appeared in What a Scream, a collection of short stories (London: Phillip Allan & Co., 1927).

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

Read on as some of the sport’s most talented writers recount their personal memories of catching bass, trout, bluefish marlin, tuna, and more. Explore the Pacific with Zane Grey, as he fights a 1,000-pound blue marlin, or listen as A.J. McClane explains just what it really means to be an angler. Take a step back in time when you read Ernie Schwiebert’s tale of fishing a remote lake in Michigan, when he was still only a young boy. Each of these stories, selected because of its intrinsic literary worth, reinforces the unique personal connection that fishing creates between people and nature. Buy Now