Once you fire up the brain stem, 1,800 pounds is immense. I figured it like this: I’d encountered aggressive dogs in my life, each one a genuine threat to life, each one fully justifying a full dump of fight-or-flight into my bloodstream. The biggest of them had been maybe 100 pounds. This ancient, bovine battering ram was eighteen times that size. And when you add in the difference in lethality between inch and a half fangs on the one side and two-foot-long horns on the other, it was electrifying to behold. He could merely run me straight through to the five-inch base of those horns, he could then toss whatever remained 30 feet up a tree. I mentally tried to paraphrase Robert Ruark’s great line about how they look at you, but the sheer malevolence of the beast stripped the frivolity from my soul.

But I wasn’t there to look at him. Rory Dickey Clark was my professional hunter. At six-foot-five, the man was a sjambok-lean 165 pounds of pale gristle from South Africa, and in the face of an animal, he was all business. He gave me the nudge, and I threw the 375 H&H Browning safari-grade bolt gun to my shoulder. I’d trained and trained with this gun, and ones very much like it, since childhood.

As the bull quartered away, I snapped off the safety. I got the clear, crisp view through the optics aligned, and moved the reticle generally in place. Then I held and half-released a breath, eased the apex into perfect position and…oh-so-perfectly squeezed off the round.

K-BOOM!

A .375 is a massive cartridge, and without hearing protection, it took a moment’s reorientation. We were maybe 90 yards away, which both gave us some margin and lost us some information. I didn’t hear the sound of the impact separate from the blast, but every other voice in the party immediately roared the hit. Without breaking my cheek weld, I cycled, and looked for the follow-up shot, but the bull was running, gone into the covering sea of cane grass. It wasn’t just that I didn’t have a responsible follow-up shot—it was that I didn’t have one at all. The vegetation swallowed him like a greased marlin to the sea and left nothing but the waves formed by the tips of the grass.

Anybody reading this probably already has an introduction to how severely dangerous a wounded Cape buffalo is. But in case not, I’ll give you a shaky-handed sketch here. Or, if you are already familiar, it’s always a good idea to remind yourself about this beast’s sheer lethality. There seems to be somewhere in that boxcar-like body a yet-unidentified organ with the volume of a beer keg, holding reagent-grade adrenaline. So long as nobody tips it over, all’s well and good. But if your first shot fails to drop him, as mine just had, then some damnable internal lever knocks the keg over and gives the buff ability to absorb ordnance like the range berm at the Aberdeen Proving Ground. The temporary stretched cavity that follows in the wake of a 300 grain 375 H&H round will readily blow up a buff’s thorax. But that, it turns out, often has no effect within the time frames you care about.

Do they kill hunters? Absolutely, and with almost monotonous regularity. The literature is already well-developed on historic buffalo attacks, so I won’t retell them all here. But let me offer that, lest you were afraid that your opportunity to get yourself stomped into a nice marinara risotto is something of Africa’s past, consider that while I have been writing this, two more professional hunters have had buffalo hand them one-way vertical tickets. That’s two professionals—in just one year.

On June 9, 2012, Professional Hunter Owain Lewis was guiding in the Chewore North concession of Zimbabwe. The term “Professional Hunter” gets abbreviated in the safari universe to just “PH,” and it gets used enough that it has become its own word. Anyway, the Chewore North concession is not terribly far from where I was on this first buffalo contact. Owain was not new to the dangerous game arena. He was 67 and described by those who knew his record as tough and experienced. Three days before, his client had landed a round in a buff, but it wasn’t a killing shot and they’d had to track the bull. For three very long days. To his professional credit, Owain would not give up. Under both the morality and the legality of it, he had an obligation not to let the animal suffer and not to expose the local populace to a murderously injured buffalo. On the third day, there were at least three people in his group: Owain, an apprentice PH and the client’s son and, presumably, trackers—the client himself not having joined that morning. Good timing.

Can you envision it from Owain’s perspective? Three days of tracking is brutal. Three days through cover when very literally every step can be a life-ending decision. Ten minutes of that is draining. Three days is nearly incomprehensible. The sweat and the adrenaline, the rightful fear, every step, having to lead the pursuit. For a full day. And no real rest at night. Knowing as you try to fall asleep that the first thing you have to do in the morning is start it all over again and that there’s a very real chance that it’s your last day. Yes, the ethos of the professional, but a crushing and horrible one. Then the second full day. Exhausted. Then, unmercifully, the third one.

You have a .458 bolt gun. It’s full-up, and you are in the lead. You know the gun intimately, which helps. You have good trackers, and that helps, too, so you can keep your eyes up while they follow the spoor. But it is now crushingly difficult to muster the laser-concentration at every second, because after three days you and everyone you’ve ever known would be rightfully and truly exhausted. Spent. Burnt. Done.

And then, after all the tension and all the work and all the fear, there’s that jittering instant when the trackers point and bolt to both sides, and after three days of brutal grind, you know.

There.

The nightmare is lying down, and for one very hopeful moment, you think it might be bled out.

But you don’t know.

You’ve long ago gone past the “only the client shoots” ethos. At this point, everyone shoots. At this point, if you had claymores, you would use them. If you could call in an Arc Light raid, you would.

You throw the weapon up and fire in one motion, the boom brutally loud, and it is joined as the apprentice PH next to you does the same, and then the client’s son joins—

And again.

And again.

And AGAIN.

But the ancient, malevolent creature rises to its hooves.

And looks at you.

It’s beyond anything Ruark ever wrote.

The numerous, solid hits from major caliber African rifles have had the impact of tsetse bites. And it comes. As it does, you have fired the last round in the magazine of the .458. So you now have a charging, wounded, Cape buff at close range with an empty rifle in hand.

Those facts are drearily reliable predictors of how this movie is going to end.

And it did. The apprentice apparently still had a round in his rifle, but couldn’t fire for fear of hitting Owain. Then as the players scrambled, the apprentice was the first to be struck by the beast, in turn slamming into Owain. One account states that the impact caused the apprentice to lose his rifle, which would both explain why he didn’t fire immediately after that, and what he was doing for the next few seconds. The survivors say that Owain held his ground, madly working on the reload.

The black monster was just oh-so-marginally quicker. It snap-turned and lunged, and the massive, thick body, with its slabs of heavy muscle and armor-like hide propelled the nature-perfected weapons on its head into the man as if he weren’t even there. With a convulsive ripple of the immense neck and shoulders, the bull completed piercing his body, hooked him and, with a violent contraction of its giant superstructure, the bull tossed him into the air. As it happened, both the client’s son and the apprentice had either recovered their rifles or reloaded or both, and they unleashed a near-contact volley.

That finally did it.

Reports to date don’t indicate where the earlier rounds had hit the buff, or what effect they’d had. We don’t know if it was a failure of the .458—something with which I have some unfortunate experience. My bet: Owain did everything exactly right. He put the bullets exactly where they belonged and the bullets performed, but the buff simply hadn’t gotten that far down its inbox yet. A post from someone who arrived at the scene shortly thereafter states that the bull lay only eight feet from the downed PH. The bottom line is that, with information just about as current as you can get, old mbogo is still very active in his local chapter of bwana bashers.

The second tragedy happened to Zimbabwe native PH Wayne Clark while operating in the Lolkisale Area of Masailand, Tanzania. Wayne, too, was deeply experienced. This is not a case of some newbie being caught with his boxers down. He’d grown up in Zimbabwe, and from childhood he’d been immersed in the arena. He qualified as a professional hunter in 1997. The reports say that the client’s first shot on the buff was a good one, smack through the fuel pump. So, too, was the second shot, placed in the last instant before the onyx monster melted away into the tall grass. With two good hemorrhaging shots, you have the age-old dichotomy: Will you find him in a bled-out heap, or will he be waiting?

As they seem to do so preternaturally well, the buff had gravitated to the heart of a dense thicket. Wayne did the right PH thing, and ensconced the client securely in the hunting vehicle before he moved forward alone. While no second-by-second account exists because only Wayne went and he did not survive, you can imagine it, can’t you? The Evil is there. You know it’s there and you know you have to go face it and you don’t make any excuses. It hasn’t tried to run out the back of the thicket, and it’s badly wounded, and you know from your 15 years as a PH what that means. It is implacable and it expects you and it will not stop but you have to go anyway.

So you take a good look around, at the topography, at the bush, at the track. You try to think of every advantage you can get. Then you check the chambers on your 500 Nitro Express double. Both loaded. Both with solids. You check and re-check that the action closed solidly. And check twice that the safety is well and truly in the “off” position. Then you sense the wind, and satisfy yourself that it’s as good as it’s going to get, and maybe even a little in your favor. A deep breath. Then maybe jostle the left vest pocket with the secondary backup ammunition. Maybe even drop a hand in to make sure it’s all oriented in the same direction. Next, you address the primary backup ammunition. That goes between the fingers of your left hand, carrot-sized rounds, long and front-heavy and comforting, held projectiles-up, sticking way out so as not to interfere with your grip on the forearm. Another breath. You take a moment to realize you are sweating now, you can feel it under the vest, and more importantly, on your hands.

Then it is time to move. Oh so slow, listening. So damn careful. Each step carries horrific meaning. Its noise can betray you, and each step can carry you into the threat’s view. Each step is critical. The 500 Nitro double gun is up, comb against your right cheek, hands pressed into the checkering, looking down the twin barrels, both eyes open. Wide open. Scanning. Knowing how hard they are to see.

Your heart rate would blow out a digital monitor. The sweat drips into your eyes.

Nobody can both hunt and track at the same time. And you know that. Knowing that you can do one or the other but not both. Your eyes flicker down to the blood trail, then right back up. Grateful that the client had nailed it so cleanly, so much blood. Hoping, really hoping, that the hits had been enough and that this one-man stalk proves wildly unnecessary.

Kneeling. Right hand on the weapon’s stock, muzzles up, eyes flickering down to the left, touching the leaves with the blood on them before starting back up again.

You are profoundly grateful for your rifle. It’s a 500 Nitro Express, and it is a truly breathtaking piece of machinery. The cartridge had long ago started life as a blackpowder round, but by about 1890 it had entered smokeless modernity. And in that incarnation, it is something fearsome to behold. It fires a projectile nearly twice the weight of the otherwise legendary 375 H&H, at a staggering 570 grains. Nearly twice. And you remember that the 500 Nitro Express steps out at 2,150 feet per second, for a total energy of 5,580 ft.-lbs. Someplace, you dimly comfort yourself that this fully adheres to Robert Ruark’s edict to “Use Enough Gun.”

You smell him first. That was the gift of the wind. It’s barnyard and it’s sweat and it’s the vaguely metallic scent of the blood that must have pooled under him while he waited.

But you can’t see him.

Until he moves. The explosion.

NOW, NOW, NOW!

Front sight.

Bo-boom!—both barrels.

Open, eject, in close.

Bo-boom!

And then that horrific instant, just before contact, when you know that it has not been enough and that there is nothing more you can do.

The giant beast took one of its horrific horns and thrust it through Wayne. We don’t know exactly where, but someplace in either the thigh or somewhat above. A slow-motion replay of the massive, ancient piece of keratin plunging into him is too awful to contemplate. But even though buff are renowned for taking downed humans and turning them into liquefied dark spots in the dust, that wasn’t the case here. It appears that the buff merely hit him and bolted.

Merely.

Wayne was alive for a period. That somehow makes it all even sadder. But the point in the context of this writing is that buff have not gotten even slightly less dangerous. They are continuing to do what they’ve done for a good 50-ish million years and as long as they draw breath, they always will.

I had all those sorts of stories playing in my head as we looked at the place the buff had disappeared. After I’d fired, I took a long minute to start breathing properly again. And another long, slow, four minutes to work our way through the 90 yards to the point of impact.

Every step in those circumstances is like walking across a frozen late-spring lake. Every nuance, every crack, every sound has supreme importance to your survival. Because the buff is probably still alive. The trackers found the blood.

There were two of them, of the Ndebele tribe. On the Great Bell Curve of Tracking, I couldn’t track a streetsweeper through a mudflat. But the trackers were superlative, nearly extraordinary. How, I truly never did figure out. But in this moment, their magic was wildly unneeded—the shot had been a clean-through heart/lung one, and bright red, fully oxygenated blood was present on both sides of the track. Helen Keller could have tracked it.

We were near the Zambezi River, on the edge of Lew’s 30-mile by 30-mile hunting concession. The ground we were on was low elevation, near river level and covered with untold hundreds of acres of tall, dense, rigid river cane grass. Much of it was chest-height, some of it was over our heads and all of it was opaque. In the places where it was low enough to catch a glimpse of the area ahead, I scanned with total intensity. But much worse was when the grass was too tall to see ahead. I was aching, stretching, projecting, feeling for some kind of sound. But the bull had been far enough ahead of us that I could hear nothing but the cacophony we made pushing through the cane grass. Patton’s Third Army had made less noise taking Metz.

My pulse was 180, and it felt triple that. We went forward like that, on one compass azimuth, for a long, long time.

Each step in that process involved my entire being. It was everything I had.

Then, in an electric instant, my tracker, Simon, shot a quick look back at me, eyes wise and concerned. He snapped out one hand, pointing. For an adrenal instant, I was lost. And then, the importance of it rolled over me. Sharp enough to lay a protractor on it, the blood trail turned 90 degrees to the left.

Wally’d told me: “You’re going down by the river, in the cane grass, aren’t you? I’ve done that, an awful lot. Once a buff’s hit, there are three possibilities. He may simply expire. Or he may bolt straight off to cover, where you will have to root him out. But the third possibility. If he runs and turns hard, it means he’s trying to switch things up. That is, he’s now the one coming for you.”

To my left the unending sea of cane grass extended, a visual snakes-and-ladders of chlorophyll and fiber, tips all slightly swaying in the breeze. I stretched up, tiptoe, weapon shouldered, just looking both through and over the 1X scope, trying to absorb the slightest off-pattern in the grass. And when that didn’t work, I went back to putting my auditory cortex on time-and-a-half.

Nothing.

Then the idea hit me. Should I top off the magazine? I wanted the additional round, but didn’t want to risk the instant of downtime. If I opened the bolt, I knew I’d lose the chambered round, too, so I’d have to top off with two. Nothin’ doin’. Muzzle up, both eyes open, scanning the cane and—

Explosive movement in the far peripheral vision….

Behind us.

Only black fragments visible through the rushing commotion in the grass, coming at a literal dead-run onto the trail behind.

In a flash, I had the understanding that he was engaged in an ancient contest his nucleic acid had played out untold millions of times and won often enough that natural selection had made it a part of him.

Then, close enough for the shot.

A flash look through the 1X scope.

No memory of the blast or recoil, onto the second round.

Oh, so damn close.

Second round away, same place.

Action open, tight against the right side.

Only time for one round in.

Thumb feeling against the mag spring, then bolt slamming closed.

Head down now for the contact.

I have a distinct memory of what it felt like to pull the trigger.

Not the sound. Not what I saw.

Just the trigger pull. Crisp and good.

The 300 grains of bonded Bitterroot .375 left the muzzle at somewhere around 2,800 feet per second, which meant it took something like .03 seconds to cover the 80 remaining feet between us. For contrast, a blink takes far longer. By the grace of God, the round just kissed the armored top of the Panzer skull and went straight into the cervical spine beyond, where it conclusively severed diplomatic relations between the brain and all the big, scary parts.

Isaac Newton dictated that the excitement wasn’t quite over. Nearly 2,000 pounds had relinquished life but not momentum, which it proceeded to demonstrate by sliding to a halt just 40 feet in front of me.

The first thing I actually heard was: “Well, that’s done it!”

Right.

I was still covering the carcass, apparently having topped off again.

Rory was close up. “Magnificent show.”

I directed my muzzle at the ground, but some bit of wiring formed someplace in the early Holocene wouldn’t let me take my eyes off the oh-so-recently malevolent creature in front of me.

Rory checked the downed monster, then the rest of the party swarmed in behind us, singing and loud, jubilant.

I then learned something about Lew and the people who worked with him. Over the years, a particular practice of theirs would become a true art form, one I came to love and one that my father, who eventually hunted with Lew, also came to love. It was this: After a particularly hairy almost-didn’t-survive-it event, while the riptide of adrenaline was still flowing through your chest, they would offer some sort of brilliantly droll, dry, understated comment.

Rory shook my hand, with his eyes narrowed in the best of humor, somewhere between smiling and laughing. And in that funny South African accent, “Welcome to Africa.” His eyes flickered down to the buff, then back up.

“I expect you’ll do.”

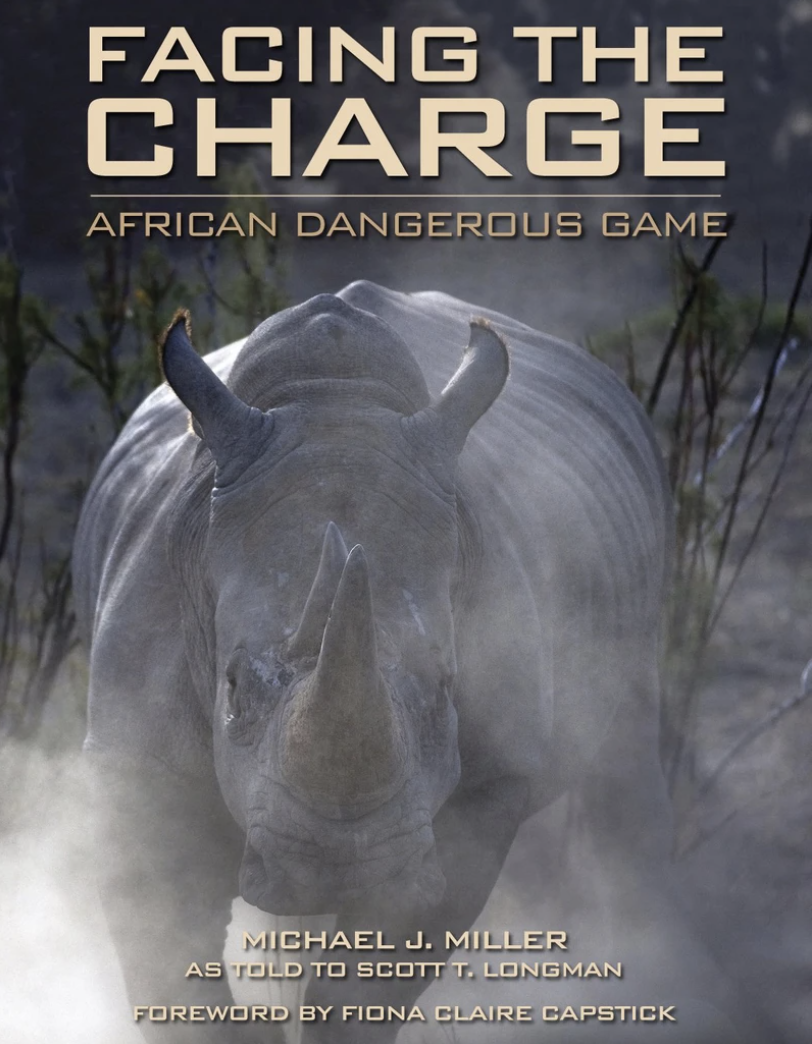

This article is adapted from: Facing the Charge by Michael J. Miller as told to Scott T. Longman. In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death is a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population and examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa.

This article is adapted from: Facing the Charge by Michael J. Miller as told to Scott T. Longman. In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death is a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population and examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa.