Last November in Scotland, a line of seven friends spaced 20 yards apart marched across a harvested field in pursuit of pheasant.

On that misty morning, hunters, dogs and gamekeepers were eager to find birds and almost immediately they did. A brightly feathered pheasant leapt into the air with a cackle and took flight.

“Bang!” Bird down.

At the shot, two more cocks flushed.

“Bang! Bang!” Birds down.

The line moved forward retrieving the downed birds, and five more pheasants rose from the far edge of the field. Five shots later, four more birds down. The Labs retrieved.

There were more flushes, more shots and more birds down. Birds in the air, guns up, shots and then twisting, well-centered pheasants hitting the ground leaving a string of feathers floating in the air.

The head gamekeeper, Garry Ford, turned to Ron Shepherd, one of the hunters, and said, “This is a true firing line!” Garry had not seen the group of shooters at work before as this was their first visit to his grounds.

Ron agreed replying, “You have no idea.”

These men of New England were experienced ruffed grouse and woodcock hunters, used to shooting at fleeting glimpses of their quarry through a screen of thirty saplings, three pines and an apple tree. For a ruffed grouse hunter, the wide-open shots were a dream-come-true.

Drummond Castle is outside of Crieff in Perthshire, Scotland. For historians, that name conjures barons, earls and, indeed, a queen; Queen Victoria visited the castle to view the famous gardens. But for hunters, something different is brought to mind – an estate of 61,000 acres with pheasants, Spanish partridges and the occasional duck or woodcock on its grounds — a shooting estate, with gamekeepers and dog handlers.

It was a pleasure watching the dogs work combing the fields and finding birds.

For five days our American shooting party was privileged to hunt those grounds. Each day was a mix of driven and walked-up shooting – it was heaven for gunners. Going away shots, incoming, crossing, towering, snap shooting through brush, long shots over open meadows — we had them all.

A mixed day is a combination of rough (walked-up) and driven shooting. That combination is the less expensive relative of a full driven day. Rough shooting is the same technique we Yankee shooters use to hunt upland birds. Several hunters in a line, with or without dogs, walk through cover and shoot birds as they flush. Most shots are going away, quartering or crossing.

Driven shooting is true estate shooting and it takes a large group of non-shooters for it to be done properly — beaters, gamekeepers, loaders, dog handlers, walkers, spotters, even cooks and bartenders. While it is possible to have a rough shoot with only one gamekeeper and his dog accompanying the shooters, a driven day needs 20 to 50 people to flush, find, retrieve the birds and support the gunners. Most driven shots are at incoming birds.

After the initial flurry of walked-up pheasant action was over, the group turned their attention to driven birds.

Dave Tilden had organized this trip of shooting friends using Jay Steel of Cowans Law Country Sports as his outfitter. Jay is a handsome, memorable woman with a warm smile and a firm handshake, a shooter with hunting connections throughout Scotland.

Jay told Dave, “The Drummond Estate is just beginning to host shooting parties. You will be in on the ground floor. Once the news gets around, it will be harder to book.”

Jay and Dave had worked together before and he knew that her advice was good. He booked the shoot, and we had the gunning trip of a lifetime.

After the initial flurry of walked-up pheasant action was over, I waved the rest of the group on and found a comfortable rock to sit upon. My aging knees had given up several weeks before the trip and I was taking things easy. Throughout our stay, my shooting partners and the gamekeepers were very understanding and posted me on the less strenuous beats. I participated only in the short walk-ups, but shot all the drives.

About thirty minutes after our firing line disappeared over a rise, I spotted a hare moving very quickly away from the shooters and toward me. I froze, remained seated and watched the speeding hare. I checked the area – no dogs around, no other hunters in view, and it was safe to shoot a target on the ground. The hare whipped through the grain field, leaped the stone wall and roared into the green and grassy field. It was cruising right along and would pass on my left. Maybe all those sporting clay rabbits were going to pay off.

Seated on my rock, I moved, mounted, shot and rolled that hare at thirty yards. The 16-bore W&C Scott side-by-side bagged its first European hare and made my morning. Soon the Firing Line was returning and walking toward me. At the edge of the field, 60 yards in front of them, a pheasant flushed toward me, flying the same line that the hare had run, so I moved, mounted, shot and folded that cock up at thirty-five yards. Whoops and shouts came from my friends who had had a ringside seat.

The group found sunny places in the courtyard, rested and ate lunch among the breathtaking surroundings while talking guns and birds.

The Land Rovers returned us to Drummond Castle where we walked into the courtyard and looked in awe at the walls, gates and battlements. As children, all of us had at some time imagined ourselves either as defenders or attackers of a castle. Now as adults, there we were and took full advantage of the situation, walking the courtyard, looking over the walls toward the garden, and finally going into the famous garden itself.

We found sunny places in the courtyard, rested and ate lunch among the breathtaking surroundings while we talked guns and birds. Six of us were shooting 16 bores, two of us 12s, and all were English side-by-sides. We’re all traditionalists and believe that gunning in Great Britain merits side-by-sides and appreciate the feel and quick response of an English double and, out of respect for the birds, the guns and the estate, some of us even wore ties and snap-brim Barbour caps.

Shooting flying and driven birds on estates has shaped at least two centuries of British gun-making. Estates mean wealth and for more than two hundred years, aristocrats shooting on these estates ordered the “best” guns. Just as their garments were bespoke and custom fitted, so too were their shotguns.

Think of their many choices – boxlock, sidelock, round action, bar-in-wood; 12, 16 or 20 bore and either tight chokes for high driven pheasant and red-legs or open chokes for lower flying red grouse and woodcock. Add a selection of highly figured wood for stock and forend, engraving on exposed metal surfaces—either something traditional such as rose and scroll or perhaps a tasteful game scene—and, of course, make it a matched pair. Both guns identical in gauge, chokes, weight, measurements, wood, engraving – all beautiful examples of the “Art of The Gun” made by hand to suit, whether in London, Scotland or Birmingham by the best artists/craftsmen/stockmakers/engravers of the respective gunmakers.

These were light, responsive, beautifully designed and engineered works of art. They mounted effortlessly, shot where they were pointed, stood up to British weather, patterned well, were inherited by the next generation and continued bringing down birds – perhaps ultimately by the hundreds or even thousands.

After lunch we drove several miles through the Drummond estate to a group of stone outbuildings and parked. The light mist of the morning had changed to cloudy overcast before noon. The sun that came out during lunch was now hidden and only a glimpse of blue sky peeked through the clouds. It felt like late fall as the air smelled wet and there were puddles and mud underfoot. We cheered the blue sky on, but it stayed Barbour weather – chilly and damp – the reason Scotch whiskey was invented.

Garry and Jay walked us to our stands just inside a fence line halfway up a ridge. Garry explained how the beaters would drive the birds over the ridge and into our line. Some of the birds would be high, others low, and to always remember the blue-sky rule— shoot only at birds surrounded by blue sky, let the low ones go for another day.

We took our positions and, with our guns broken, faced the nearby ridge. In the distance were more hills and ridges — pasture, bracken, a bit of marsh and then a crest of pine trees — just a slice of the shooting estate prepared and ready for us. The gamekeepers had raised and released the red-legs and pheasants, put out medicated feed, counted and worried about, tracked and planned, planted and cut and burned and fertilized. A hundred days had been spent in preparation for this one day, our day.

Left to right: Taylor Thompson, Randy Croote and Pete Stanley with their side-by-sides in hand and close to their hearts.

It was some time before the birds got to us. The beaters were off in the distance out of our sight in a carefully planned and guided line walking toward us. Their dogs walked with them under control, well-trained, eager and happy. Labradors, springers and cockers, flushing dogs, dogs to put the birds in the air. The beaters used walking sticks for support in the rough going and they waved and flapped flags. They called directions to each other and laughed as they saw birds flush toward us and flapped their flags and arms to turn birds that tried to make an end run behind them. Forward, ever forward.

Ron was a bit downhill on my left and Taylor Thompson was 30 yards uphill to my right. The other shooters were out of sight. The blue sky rule was important. We had to keep away from low birds to protect beaters and fellow gunners.

The hunters were experienced ruffed grouse and woodcock hunters used to shooting at fleeting glimpses of their quarry.

On the left, Jay was talking to Ron and I heard him laugh and saw Ron load his gun. Jay gave me a thumbs up and also loaded his shotgun. Jay signaled Taylor and word went up and down the line. “Load up. Birds soon.”

We waited. I mounted, swung my gun, and did some twists to loosen up my aging body. I heard Jay laugh again and then heard a shot from the far left. Russ Hughes had opened the ball and there was a dead Spanish partridge in the brush behind him – work for the dogs. I resisted the urge to look, kept my eyes focused forward and saw a hen pheasant break toward Taylor giving him a curving shot up the hill to his right.

A shot, feathers in the air and Taylor’s bird struck the ground. I turned from watching Taylor’s shot and looked as a rocket whooshed past me 10 feet up. Distracted, I had no time, no shot. Eyes front, focus! Get in the game.

Two shots came from my right. It was one of those hurried “bang-bang” that signals “behind-behind” and then another shot came from the left where Ron was at work grassing a long-tailed and colorful cock pheasant.

Taylor yelled, “Bird!” and I swung right, mounting as I looked and fired a fast snap shot at a high red-leg. Feathers puffed in the air and a crumpled heap landed behind me. “Thanks, Taylor!” I called out and turned face first into a cock pheasant hurtling over the ridge. Blue sky, another fast shot, and down the rooster came.

A hundred days had been spent in preparation for this one day, our day.

There were more shots from both the left and the right. Brian Fawcett, Randy Croote and Pete Stanley were all at work as the driven birds come faster. I shot another red-leg and as I was reloading, another flew past unharmed. Two more shots came from Taylor and I couldn’t resist looking his way. Taylor shouted and I saw three red-legs, two dead in the air and the third heading behind me. I turned, took a high crossing shot, and splashed that bird in the river 40 yards away.

And then it came.

The flurry that we’d all heard about—bird after bird, in pairs, singles, flocks, often with red-legs and pheasants mixed together. We shot, reloaded and shot again. Oaths were sworn at fumbling fingers as live shells dropped to the sodden ground. Barrels grew hot such that we felt the heat through our gloves. This was the hot frenzy of driven shooting. The birds flew at us, over us, to our right, to our left, high and low. Some hit the ground, but many more flew on.

Ron made a bragging-rights shot in the flurry with a right and a left, striking down a red-leg flying directly at him with the right barrel and then a breaking away cock pheasant with the left barrel. It was fast, instinctive shooting. Then, after the heart-pounding time with the guns and the birds, came the horn, the signal that the beaters were too close for safe shooting.

We unloaded our doubles and laughed as a few late flying pheasants flew past. Over the ridge came a group of dogs, women and men. They were the people who had worked so hard for our sporting pleasure. We smiled and talked, pointed out where birds had gone down, admired the dogs and watched the superbly trained Labs and spaniels at work.

Gunning in Great Britain merits side-by-sides and the feel and quick response of an English double.

Ron walked over and picked up a Spanish partridge – the first half of his red-leg/pheasant right and left. A Lab already had the pheasant in his mouth and was trotting back to his trainer. It was such a pleasure watching the dogs work combing the fields and finding our birds.

We greeted our fellow shooters and walked with the dogs, gamekeepers and beaters back to the cars. With stories told and memories shared of dogs, shotguns, the grounds, the birds, shots made and missed, the best part of the day was that we would get to do it again tomorrow.

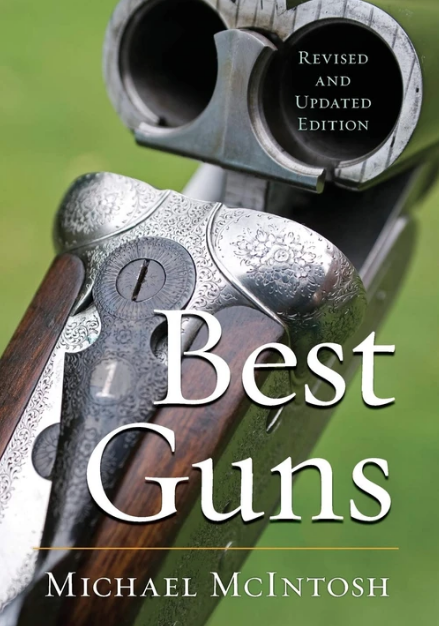

In this second section, Michael McIntosh explores the revivified world of gunmaking abroad–in England, Spain, Italy, and elsewhere, places where traditional craftsmanship and modern technology have combined to make the turn of the twenty-first century the most vibrant and exciting period in fine gunmaking in nearly a hundred years.

In this second section, Michael McIntosh explores the revivified world of gunmaking abroad–in England, Spain, Italy, and elsewhere, places where traditional craftsmanship and modern technology have combined to make the turn of the twenty-first century the most vibrant and exciting period in fine gunmaking in nearly a hundred years.

McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting, and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

As interest in fine double guns reaches a new high in this country, Best Guns serves as both a guide for the uninitiated and a standard reference for the experienced collector and shooter, all written with the precision and seamless grace that were Michael McIntosh’s trademark style. Buy Now