“My goal is to keep drawing in as much money as possible for conservation…It’s good for wildlife, and a good challenge to try and set new records.”

On a snowy Saturday morning deep in the winter of 1969, my father asked me a favor. Would I help him haul the prizes?

Terry Redlin

Would I? Good God, I’d have killed for the privilege. Stacked to the rafters in our basement was a 12-year-old boy’s dream: shiny shotguns, case lots of magnum shells, hip boots and waders and duck calls and decoys. All of it new. None of it was for me. With covetous eyes I’d watched that mountain of sporting goods grow as my father and his duck hunting cronies added to the pile. For weeks they had scoured the streets of Green Bay, Wisconsin, strong-arming hapless merchants for donations. The goods would become door prizes and auction items at their upcoming Ducks Unlimited banquet. Old Beno had recently scored the biggest kill of all, extracting a snowmobile from the local dealer. How would we get that in the basement?

It would stay with the dealer till auction time, Dad grunted, as he and I hauled boxes out to the car. We were to meet the newspaper photographer in an hour.

“Passel of Prizes,” the photo caption read, instructing readers where and when they could win the stuff. Pictured above the caption was Old Beno. Seated on the snowmobile, buried in a king’s ransom of sporting goods, he beamed so broadly his face could have lit up a coal mine. He was helping the ducks.

My father and his friends raised $4,000 at their dinner. They were but one of some 300 volunteer committees nationwide that generated $1.6 million that year. Big money, to be sure. But what those good duck hunters didn’t know at the time was that they were on the cusp of something huge. DU was about to build a fund-raising machine the likes of which had never been seen in wildlife conservation.

Ducks Unlimited’s fundraising formula [then began] to produce $68 million per year. Wildlife groups beyond count have cloned this formula, raising dollars to benefit pheasants and quail and turkeys and deer. The formula owes its origin to one simple thing: wildlife art.

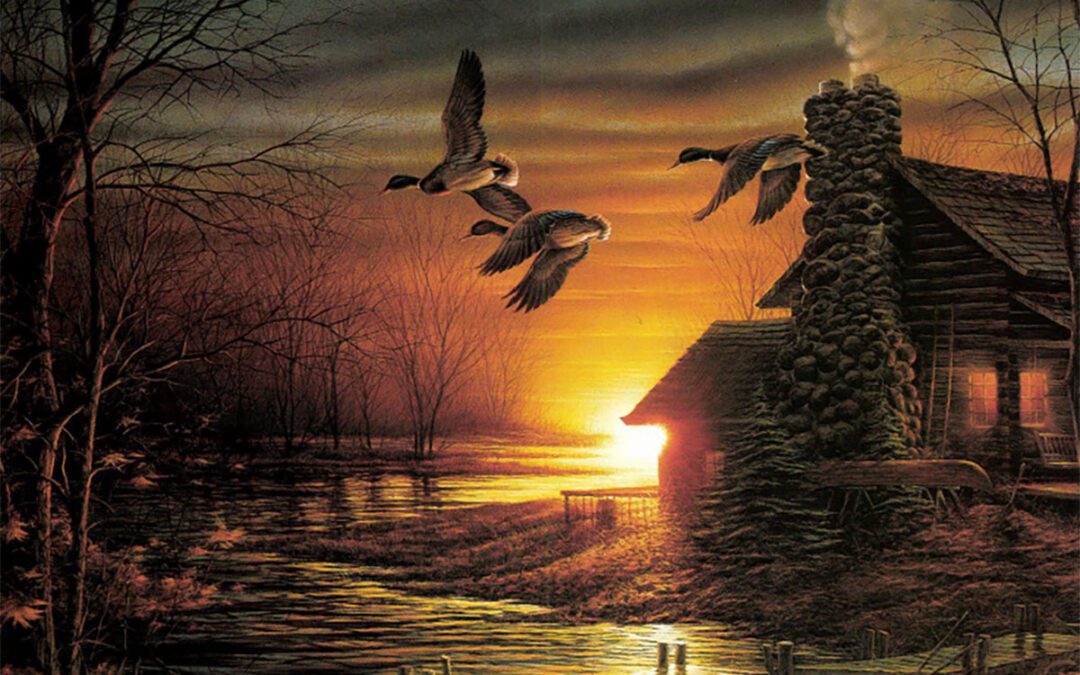

David Maass‘ slashing canvasbacks on the wing … Jim Killen’s snow geese descending to frozen fields of picked corn … an idyllic cabin in the autumn woods as brushed by Terry Redlin. Such are the images that have come to embody the successful symbiosis between wildlife artists and conservation organizations. How successful? Between 1971 and 1991, Ducks Unlimited sold 535,000 art prints, generating about $81 million. Today, just one print edition by Terry Redlin will raise something in the neighborhood of $3 million for DU.

The best part about this raging success story is that it was never foreseen, let alone planned. A boatload of MBAs with spreadsheets couldn’t have done any better than what a group of duck hunters just sort of fell into back in 1970.

David Maass

“It came about on a plane, as we were coming back from our annual convention in San Antonio,” says Ken McCreary, DU’s executive secretary McCreary came to the organization in 1965 with Dale Whitesell, the man today credited as the builder of Ducks Unlimited. Gaylord Donnelley, a printer by trade, was then a DU officer. Donnelley had an idea. “Gay mentioned that he had a hunting friend named Jim Lockhart, who had painted a picture of green-winged teal. Lockhart said he’d be happy to grant reproduction rights to DU,” McCreary recalls. “Gay suggested we do a limited edition, and offered to donate the paper and printing through his company. Sounded like a good idea to me.”

Up until this time, DU fund raising revolved around all the ice augers, motorcycles, hunting trips, and bottles of brandy that local committees could scrounge. Nothing was provided from DU National Headquarters. How would this print thing go?

Donnelley’s press ran 500 prints of Green-Winged Teal, more than enough to cover the 455 chapters that would hold dinners in 1971. Lockhart’s prints averaged $299 a pop on auction, translating into nearly $150,000 for the ducks. It didn’t take the DU brass long to decide what to do next.

DU started its Artist of the Year program in 1972. Ohio artist John Ruthven was tabbed as the first painter, and his Oak Grove Pintails duplicated the dollar figure of Lockhart’s print. And then things really started rolling.

Edition sizes mounted as DU membership grew — first 500 prints, then600, then 850, and even 1,000. Through 1977, one edition was offered per year. Then two, then four, then eight and more. In 1990-1991, DU offered its committees 17 prints in various edition sizes ranging to 5,600. The chapters sold 61,400 signed and numbered prints, raising about $10 million.

Since limited-edition art worked so well, why not shotguns? In 1973 DU National offered its first shotgun, a special-edition Remington 1100 commemorating the 1100th project in Canada. Limited-edition liquor decanters followed. There were knives, too, and collector’s plates, etched crystal, field glasses, sculpture — even a limited-edition golf club.

Jim Killen

From putters to pewter, DU sold it all. Meanwhile, wildlife artists continued to offer their work. David Maass, Maynard Reece, Les Kouba, Owen Gromme, and Lee LeBlanc were some early names, their paintings raising hundreds of thousands as edition sizes grew. Then, in 1981, came a fellow named Terry Redlin. DU dinner goers, used to framed marsh scenes, were captivated by a woodsy log cabin vignette entitled Morning Retreat. It was the first million-dollar print DU ever did. With Redlin’s continuing help, it was far from the last.

“That painting was the beginning of my association with DU — it was one of the first donation pieces I’d done,” Redlin says. “My theory back then, and today, is when you donate, donate your very best work and good things will eventually come back toyou. At the time I had a half-dozen paintings in the works. My wife and I sat down and picked the best out of all of ’em, and that was the one.”

Redlin’s artwork has paid off quite handsomely for wildlife conservation. Golden Retreat, DU’s 50th anniversary print, brought a record $2.9 million! Since 1981 seven Redlin prints raised $15.1 million, another record. It must be stressed that this figure only reflects what Redlin’s art has raised via DU’s national print program. It is impossible to quantify just how much Redlin — or any other artist — has raised for DU. These artists have donated works on the local and state levels for decades.

Jim Killen is a good example. Each year the Owatonna, Minnesota painter donates an original to his friends on the Rockford, Illinois DU committee. He has done so for 24 years.

“The reason is my strong, strong feeling about DU, and the good it is doing,” Killen says. “Without reservation, it’s the number one conservation organization in North America. This is my small way of contributing to the movement.” Through the years, Killen has been the most consistent contributor to the national print program, producing six editions that have raised $4.5 million. His consistency is not surprising, since he literally lives conservation. His 160-acre farm is open to school kids to learn about, and get involved in, conservation. The Killens have planted 5,000 trees, established 17 acres of native prairie plants, and excavated two duck ponds.

Maass’ Greenhead Alert, a highly successful piece at DU’s Flyway Print.

From mallards circling farm ponds to canvasbacks sizzling across leaden skies, the birds in David Maass’ paintings hold a special appeal to waterfowlers. “I am a hunter, and all I’ve ever wanted to do is paint for the sportsman,” says Maass, the only painter to be twice chosen as DU’s top artist (1974 and 1988).

A percentage of every Maass print series is set aside for conservation causes. “I can’t think of a time I turned down a worthwhile organization if they wanted a print,” he says. For the past quarter-century Maass has been heavily involved with DU. He is a major donor of cash and an honorary trustee. Beyond prints, he’s given originals, designed the organization’s 40th anniversary logo, and made medallions to grace the receivers of shotguns.

“To me, Ducks Unlimited is the conservation organization in this country I thoroughly believe in the work it is doing,” Maass says. “Anything I can do for them, I will, unless I just don’t have enough time. I did four engravings for their shotguns, because I felt it was an honor. I didn’t look at it as ‘Jeez, they’re trying to get another job out of me.’ I feel good about what I do for DU…and without DU, I don’t know if David Maass would be a successful waterfowl artist.”

The list of successful waterfowl artists who have participated in DU’snational program is long. Lynn Kaatz, Ron Van Gilder, Robert Abbett, Ralph McDonald, Andrew Kurzmann, Jack Cowan, and David Hagerbaumer have participated consistently.

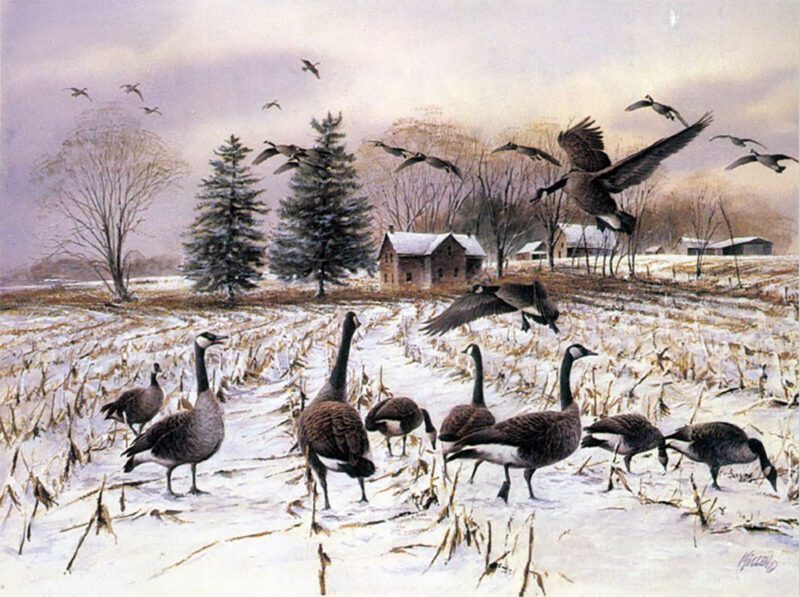

Killen’s Sharing the Land – Canada Geese, another hit at DU’s Flyway Print.

These contemporary painters, and many more, represent the second generation of artists who have gone to work for DU. Their predecessors include such luminaries as Frank Benson, Roland Clark, Richard Bishop, J.D. Knap, Lynn Bogue Hunt, Francis Lee Jaques, and Ogden Pleissner. All lent their considerable talents to the organization through the 1930s and 1940s. Their art was not used to raise funds, but instead, for illustration and a series of “membership certificates” issued from 1937 through 1967.

Today’s artists are in fine company indeed, and say they intend to maintain the tradition. “My goal is to keep drawing in as much money as possible for conservation,” Redlin says. “It’s good for wildlife, and it’s a challenge to try and set new records.”

“I’m proud to be involved,” says Jim Killen. “I will continue to do whatever I can, for just as long as I can.”

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1991 Sept./Oct. issue of Sporting Classics.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now