Remington called it “The Gamemaster.” Serial number 260,000, one of more than a million made between 1952 and 1982.

We met on the beach. I was doing turtle work for the DNR, she was on vacation. I was registered with the Feds with authority to possess and transport endangered species. I figured she was an endangered species; she figured I was, too. Seems we both were right. Talking about Miss Biscuits now. She came with two boys, knee-high when I gottem. We married on a boat in the middle of the river. It was a 1913 Trumpy motor yacht, 60-some-odd-feet but Coast Guard rated for only 28, a much shorter guest list that way. We stood by to repel boarders should there be any interruption by sundry exes. Wasn’t necessary, just occasional heckling from the bank.

Miss Biscuits came with quite a pedigree, a Baylor out of San Antone. One uncle founded the university of the same name, one died at the Alamo and yet another rode with Buffalo Bill. There was furniture that came apart with pegs and wedges for transport aboard covered wagons, assorted pioneer chairs, a monogramed cigar case from the Wild West Show, and an upright piano nobody would play and so out of tune, nobody could.

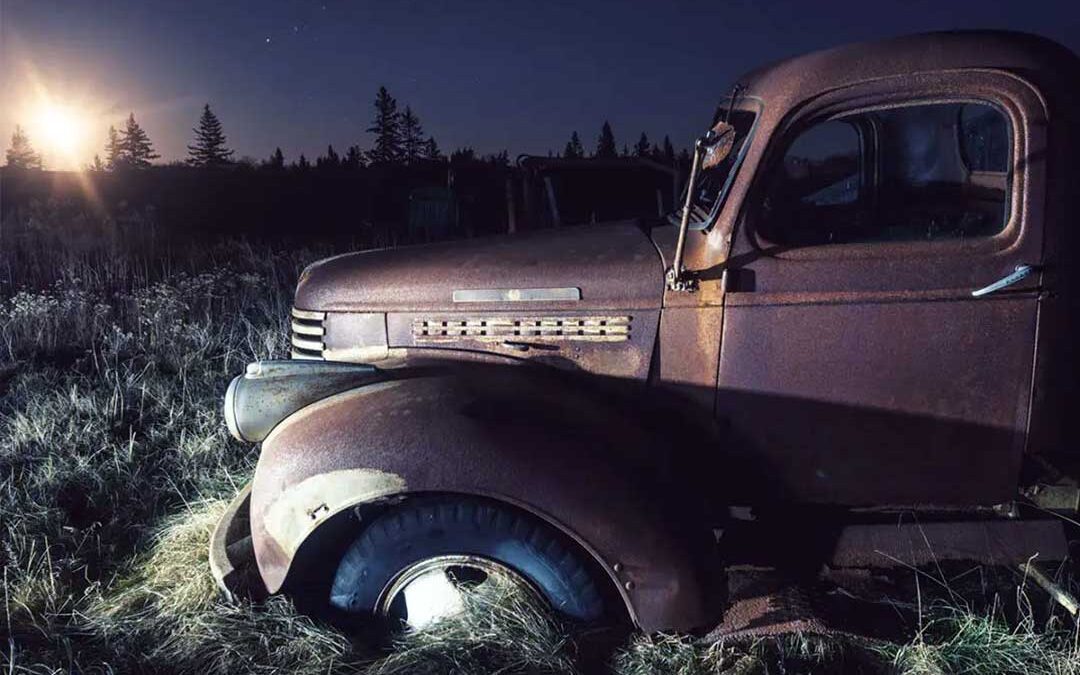

And then there was a mossy old Remington pump rifle, circa 1956, with a four-power Bushnell Banner scope and looking through it was like looking down a muddy culvert.

Miss Biscuit’s pappy picked up the tale: “The gun was purchased by my grandfather, Roland N. Baylor. He shot many South Texas whitetails with it. When the gun was passed down through the family, it always came with a ’49 Chevy pickup that was the learner car for the boys. My Uncle Raymond owned a cattle ranch in Carrizo Springs and used the gun for hunting and the pickup on the ranch during the times when there were no boys.

“When I got my driver’s license, my uncle passed down the gun and the pickup to me. I drove Mary to high school every day in that thing. We lost the key and we hot-wired it. There were six rattlesnake tails in the glove-box and the brake pedal went clean through the floor.” Gotta love Texas.

Meanwhile, the gun went out West after mulies. Another Baylor had a ranch near Marfa, way out in the Trans-Pecos high desert, just north of the Big Bend of the Rio Grande. That’s when the rifle got scoped, as those West Texas shots were long ones. That Bushnell was a middling good scope in 1962.

“My daddy would never shoot a deer he would not mount, and he mounted every one he ever shot,” Pappy recalled. “He hung lights on the antlers each Christmas. The house got brighter and brighter, year by year.”

Fast forward 50 years. Boy One was already killing deer with buckshot out of an old Ithaca double. Boy Two helped him gut and drag and skin and quarter. “Hey son, you ’bout ready to try this yourself?”

“I think so,” he said. He was already rolling beer cans with a .22. Pip, pip, pip. He was a natural.

Remington called it “The Gamemaster.” Serial number 260,000, one of more than a million made between 1952 and 1982—full rifles, carbines, deluxe with hand-cut checkering on premium walnut, the most popular pump-action big game rifle ever.

The Gamemaster came in a wide assortment of calibers, from .223 Rem. to .35 Whelen, which is a .30-’06 opened up to .35 caliber. This one was in .270, the same ’06 squeezed down to seven millimeter. But as Americans by then had a generous plenty of metrics being thrown at them—sevens in Cuba and eights in France. Winchester called it the .270, even though it measured .277, very close to a true seven, .284.

The .270 cartridge was initially a dud until writer Jack O’Connor took a shine to it back in the 1930s. O’Connor killed 36 species of game with the .270 and used it in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, India and Africa. Some of the large game O’Connor shot with the .270 includes eland, zebra, black bear, elk, 12 moose and two grizzlies. Maybe Jack stretched it a bit with the bears, but it’s a fine, flat-shooting cartridge for open country, though a bit much in this maritime jungle where a man sometimes has trouble seeing his own feet, much less a deer at even a hundred yards.

A bone- and brush-busting Whelen would have been a better choice if I had the luxury of a choice, which I did not. The rifle was a Texas family heirloom, and thus sacred, so we made it work as best we could.

No telling how long since it had last been fired. Thirty years? Fifty? Looking down the bore was like looking through the scope—scant praise. But it cleaned up quick with a generous application of love, Hoppes #9 and some liberal bronze brushing. A dozen passes with pillow ticking swabs cleaned up the swarf. The lightest lube and the bore was instant 1956.

Parts were still available through Gun Parts Corporation and schematics were posted online. That murky old Bushnell had seen its day, fare-thee-well. The rear sight was gone, discarded many years ago when the rifle was scoped. There were three possibilities for replacing it, but only one correct.

I reasoned the earliest rendition most likely and I was right. And those four tiny little screws filling the blind holes that secure the scope base? You know, the ones everybody throws away? Don’t ever toss them again. Replacements were half the size of a grain of rice but still eight bucks apiece.

What kind of ammunition? As the .270 is a renowned open country rifle for game up to and including elk, most bullets were pointy spitzers from 120 to 130 grains and blistering quick. Though no bullets are immune to deflection in leaves, twigs or grass, some are less prone to go astray.

I found something perhaps more appropriate to the tangle at hand in Federal’s “Non-Typical” whitetail line, a 150-grain, round-nose bullet at 2,800 feet per second, an entirely civilized velocity, about the same speed as the beloved .30-’06. I ordered up two boxes and Number Two Son and I lit out for the range, a dirt pile a hundred yards from the edge of the river at the butt end of Barge Landing Road.

Windage was applied to the dovetail rear sight with gentle taps from a 10-ounce brass hammer that would not mar the steel. First shot was nine inches to the left, tap, tap, soon only one. Another quick tap and it was dead on but low. The notched elevator wedge brought the bullet holes into the bull’s-eye at 100 yards, four inches low at 200, perfect.

So, I got the girl, I got the boys, I got the furniture and the piano nobody plays. I got the gun and the gun is ready for the woods. But where in the hell is that ’49 Chevy?

I ran it by Miss Biscuits’ daddy. “I wish I knew,” he said.

But I got the stories, and that will suffice for now.

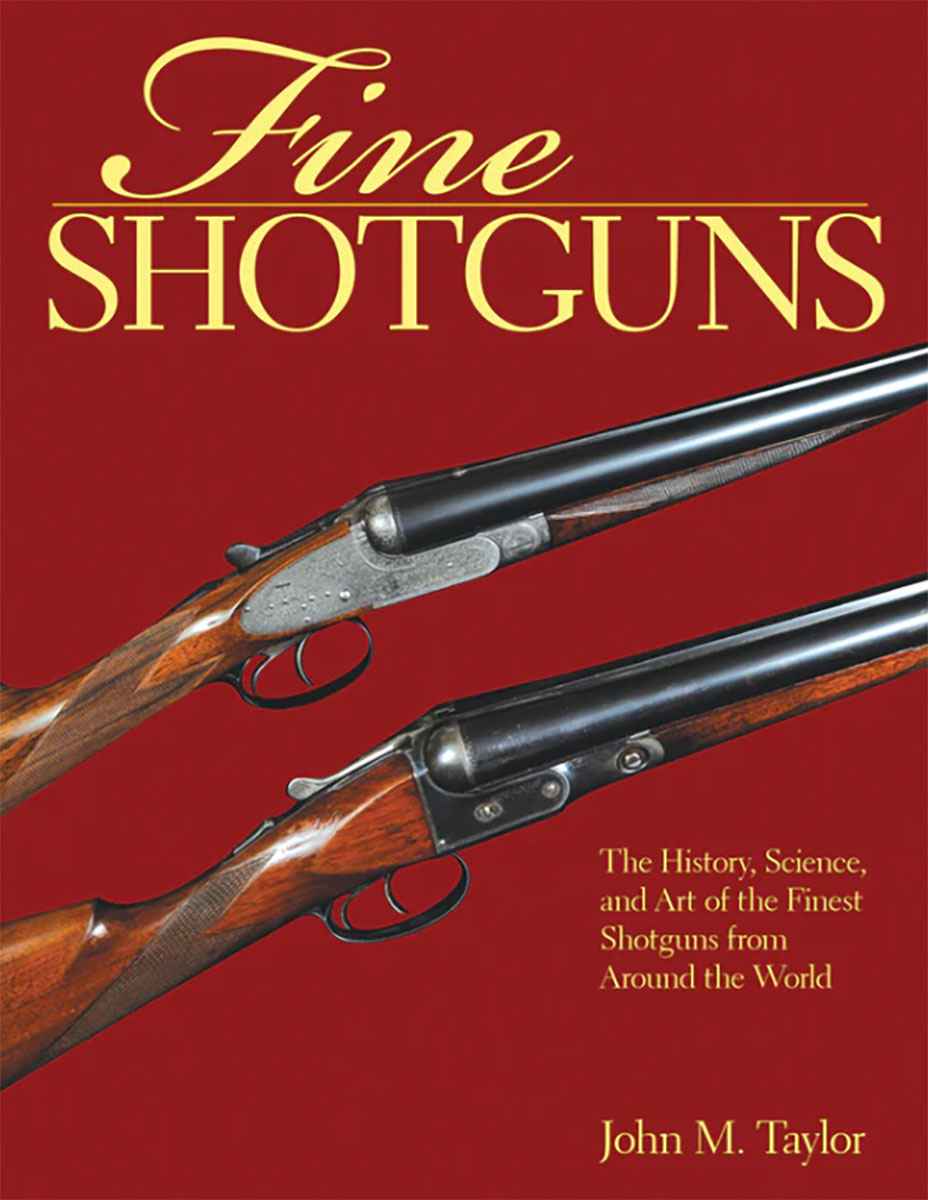

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes, and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case. Shop Now

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes, and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case. Shop Now