“Shoot!” But the client shook his head. The bush was too thick. Seconds ticked by as if on a fuse. A cracking of limbs, hoof-thunder and dust took the beast away. “So close you must get!” Rui chided. “If bull charge, I have time for just one bullet! If I miss brain — you, me finished.” He snapped his fingers.

The Portuguese PH would see “almost shots” again, shots easily made with a rifle. Bob Swinehart carried a longbow. Though sharp and heavy, he explained, and driven by 90 pounds of thrust, his arrows would not plow straight through Angola’s thorn, or through the skulls and big bones of game such as buffalo. Because those missiles traveled slowly in steep arcs, he had to get very close.

Rui Almeida must have been astonished, then, when several days later his client suddenly dashed alongside a herd of startled buffalo, leaving his PH to catch up. Nocking a shaft as he skidded to a stop, he gave one of the galloping brutes “a long lead” and released. The arrow flew 35 yards and struck forward of the scapula. The animals vanished “in billows of dust and thorn bushes.”

The hunters found the buffalo dead 83 yards on, its jugular severed. It was Bob Swinehart’s first African big game. It would not be his last.

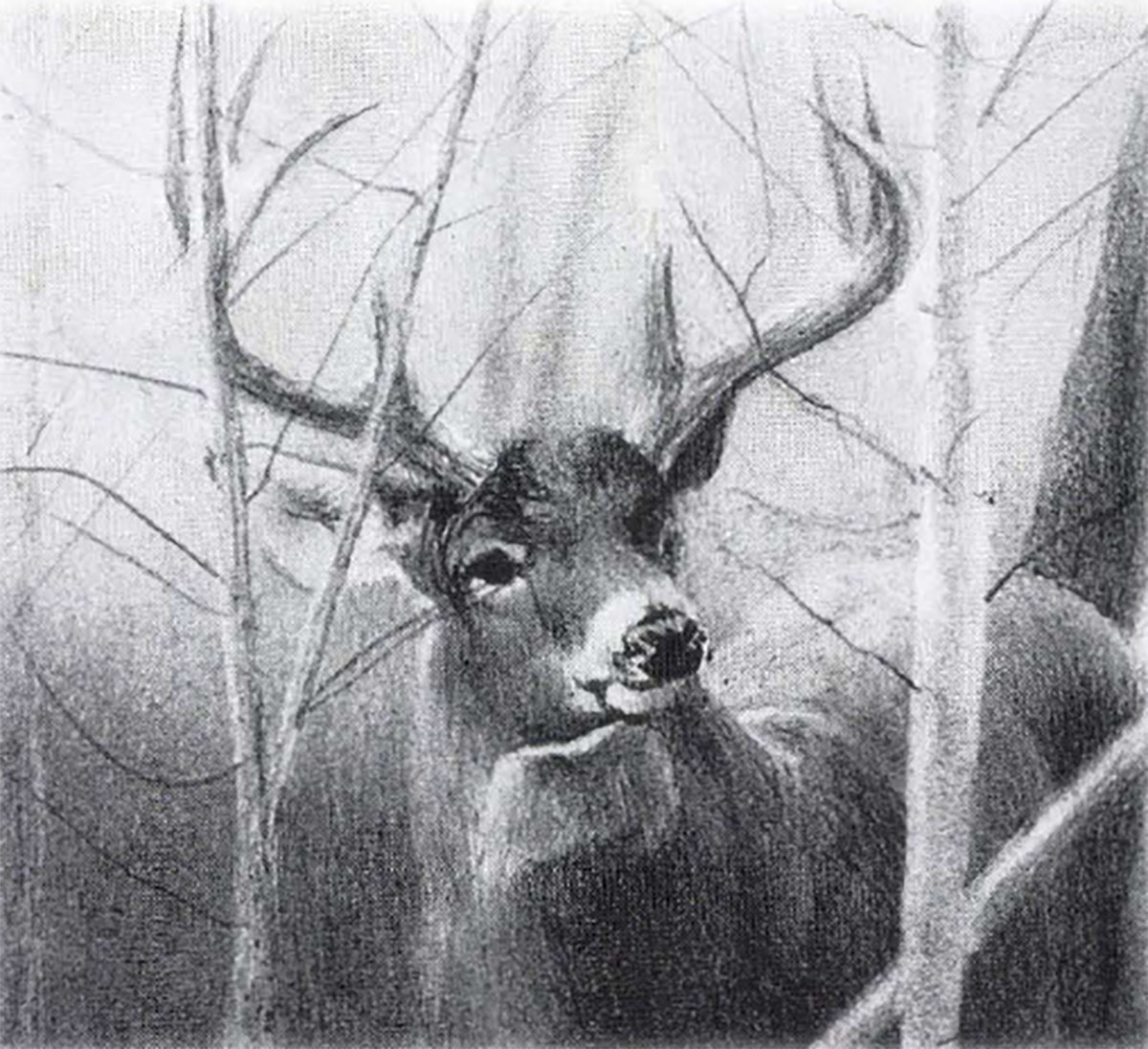

Swinehart’s book, Sagittarius, takes its title from the zodiac’s centaur. Photo: Doug Van Howd

In night’s sky, Sagittarius is a large S-shaped constellation where the Milky Way glows brightest. Beyond it lies the middle of our galaxy. It is also the ninth of 12 constellations comprising the signs of the zodiac. Completed in diagram, Sagittarius is a centaur: half-man, half horse, with a bow at full draw.

As a lad, I was mesmerized by Archer’s Bible, an exhaustive catalog from California’s Kittredge Bow Hut. Cover art by Doug Van Howd was based on the zodiac image of Sagittarius. Van Howd would later illustrate Sagittarius (pub. 1970). This book traces the life and adventures of an archer bent on taking Africa’s “Big Five” with a longbow.

Robert Neiffer Swinehart was born in 1928 to Viola M. (Neiffer) and L. Stanley Swinehart. His father’s small farm, Brookside, lay a few miles from Pottstown, Pennsylvania, then a rural community of 19,000. Bob grew up with a younger brother and four sisters. At the farm and in his mixed-race “Chicken Hill” neighborhood, he blossomed normally as a child. He played football and baseball on vacant lots and caught suckers by hand in a sluggish creek. He fell from a pony and out of a tree and ate too many green apples. The Depression limited vacations, but his two older sisters took Bob to movies featuring “Howard Hill — The World’s Greatest Archer.” For his 12th birthday he got a Ben Pearson lemonwood bow.

Athletically gifted, Bob played every high school sport he could, lettering in four the same year. Oddly, he had “no interest at all in learning to drive.” He preferred walking “unless pressed for time.” The difficult path would continue to draw him, whatever the ensuing delay or hardship.

One summer at a youth camp, Bob planned to canoe with six pals to a distant lodge. The second day out, two boys tired of paddling and with one of the three canoes turned back. Their companions went on with the other craft, albeit now unsure of the way and impeded by difficult portages. A rapids smashed the wooden canoe and left its aluminum counterpart “bent like a pretzel.” After the three days allotted to reach their destination, their food ran out. By week’s end, the lads were gaunt. One had a .22 rifle but had forgotten cartridges. Attempts to forage failed. At last Bob spied the lodge. To reach it, he and one of the others had to scale a cliff and swim across a large bay. Arriving, he “tried standing, but could not.”

Swinehart plowed through four years of college, graduating from Kutztown State. Three years of military service during the Korean War followed. Returning to Pennsylvania, the young man settled in Emmaus, where he would later own a travel agency and a contracting business. But the first day of his 18-years there proved pivotal. In the newspaper he read the local Fish and Game Association was organizing an archery club. Though he hadn’t shot a bow “in several years,” he attended the meeting.

To his surprise, he was elected president of Unami Bowmen, the area’s first field archery club. That re-introduction to the bow would inspire hunts with his four children in Blue Mountains foothills, and solo jaunts with only his bow, arrows and “a pocket full of pretzels.” Those pretzels would become a Swinehart staple in hunting camps. His favorites came from the Bachman and Unique Bakeries, both in Reading, Pennsylvania.

Swinehart hunted deer in his native Pennsylvania, and traveled to Canada and the West for other game.

In 1959, for Emmaus’ Centennial celebration, Bob invited Howard Hill to exhibit his skills on the high school football field. Hill wowed the audience by hitting tossed dimes. The event sparked a decades-long friendship between Swinehart and Hill.

Hill’s influence on archery is hard to overstate. To Swinehart, Alabama’s famous bowman was mentor and idol. Swinehart became the ideal protégé, eager to learn and quick to master skills. Soon he was wielding a longbow expertly, and booking exhibitions. Calling Hill an “intelligent, well-read man,” he cherished his tutelage and marveled at the “impossible shots” Hill made routinely in exhibitions — also at his ability to draw bows as heavy as 172 pounds!

Hollywood’s spotlights found Hill in 1937. Production of “The Adventures of Robin Hood,” starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, required an off-camera archer of extraordinary skill. Few if any men could have filled that role like Hill.

Splitting an arrow is exceedingly difficult with a longbow, even given the crescent-shaped head Hill used. He got a clean split on film with only nine shots. Six of those struck the target arrow! He was also tasked with hitting steel plates strapped to horsemen riding at a gallop. Hidden by clothing, the plates had thick balsa faces to catch and hold the arrows. But Hill noticed that with each stride a horse imparted nine inches of rise and fall to the target! Timing also mattered when Hill arrowed “enemy soldiers” hurling spears. “To throw, a man must rotate his body. I had to send my arrow the instant the fellow turned….”

In the making of “Robin Hood,” Hill’s shafts hit 45 balsa slabs on stunt men. The finished film, in 1938, showed 11. No injuries resulted. Hill was paid $150 a day plus $100 per hit. He appeared briefly in the tournament scene with the split arrow. Warner Brothers spent $2.03 million to earn $3.98 million.

Talent scouts didn’t swarm Swinehart; but neither, apparently, did he suffer the sting of envy. “A super SUPER star,” he wrote of Hill, who despite his fame remained approachable.

In Sagittarius, Swinehart detailed his choice of archery tackle, patterned predictably after Hill’s. He preferred the longbow to the recurve, insisting as did Hill that it is more forgiving of shooting error and easier to shoot from unorthodox positions. A longbow, he wrote, is less likely to hang up in brush and easier to string without twisting a limb. “The design of the longbow makes it by far the quietest bow of any [and] a long, straight-limbed bow can accurately propel a much heavier arrow than a reflex or recurve bow or any short bow.”

Swinehart preferred long bamboo limbs with fiberglass backing and facing. A “tempered bamboo bow” on the Hill design “has 75 percent of its strength in the bamboo and only 25 percent in the fiberglass facing on the belly and back. All commercial fiberglass bows with the hardwood core are just the opposite — nearly all their strength is in the glass.”

While a bamboo longbow looks simple, he noted, it is difficult to tiller properly, and doesn’t come cheap. “Mine cost from $75 to $125.” The Japanese bamboo he liked was expensive “and must be heat treated under pressure, in layers” whose number, thickness and width determined draw weight. Swinehart advised hunters to pull the heaviest bow they could control. A bow, he added, shouldn’t be clenched. To prevent his from shifting when steadied loosely by a sweaty hand, he preferred a straight handle covered with rough leather.

Top to bottom: Swinehart liked Hill’s long 160-grain broadhead, here with GrizzlyStik and Zwickee heads.

While he used Port Orford cedar shafts for years, Bob switched to fiberglass for its durability. He drew 28 inches and favored aggressive fletching: long, high and strongly helical. As regards the direction of spiral, he wrote “I don’t think it matters.” A left-hander, he did hew to conventional wisdom, ordering right-wing feathers. Swinehart hunted mostly with 160-grain Howard Hill broadheads. He mounted them with the two blades vertical so “the barb will bite into my knuckle,” preventing overdraw, and because it appears the same as a target arrow at anchor. He made his own strings of Dacron, with Flemish splicing.

As to a shoulder quiver and accessories, Swinehart found his mentor’s choices worked well. He used whale bone inserts in his shooting glove, cut and ground from a chunk of baleen Hill had given him.

From the outset, Swinehart reveled in the hunt, even under tough conditions. “I’ve had some of my most rewarding moments…in the stormiest, wettest, miserable days….” Probing the Adirondacks for deer, he and a pal once found themselves 12 miles from trailhead at dark. “We stayed the night [in] cold rain without food or shelter and really were not dispirited by it.”

Swinehart traveled repeatedly to Newfoundland’s bleak barrens, driving non-stop “48 hours (12 of them on a ferry), 1,700 miles” from Emmaus. “I do really like Newfoundland,” he enthused, “and God willing, I’ll return [to] slush the bogs…. If beauty isn’t a caribou silhouetted on a ridge at sunset across harvest-colored grass, or snow glistening over covered streams and evergreens, then the word has never been fully defined.” Recalling his 1965 trip, he noted the rate for a week’s hunt was “most reasonable” at $150. That sum covered food, lodging and the guide’s fee.

A western hunt for a black bear brought Swinehart under a big boar treed by hounds. The arrow flew true, but the bear snapped off the shaft and climbed higher, all but vanishing in the top-most boughs. Bob decided he’d have to climb to finish what he’d started. Limbs, twigs and foliage became an almost-impenetrable screen. By the time he had a shot alley, only 10 feet separated hunter and quarry “50 feet off the ground.” Somehow, Swinehart drew his 60-pound bow and sent a shaft through the ribs. And another. Then unexpectedly, the tenacious beast reached for him! His only option: a tightrope-walk out on a limb. Bow and quiver now hung nearest the bear but “would not have done me any good anyway.” Swinehart’s branch was about to yield when, with less than a yardstick between them, the bear expired and fell.

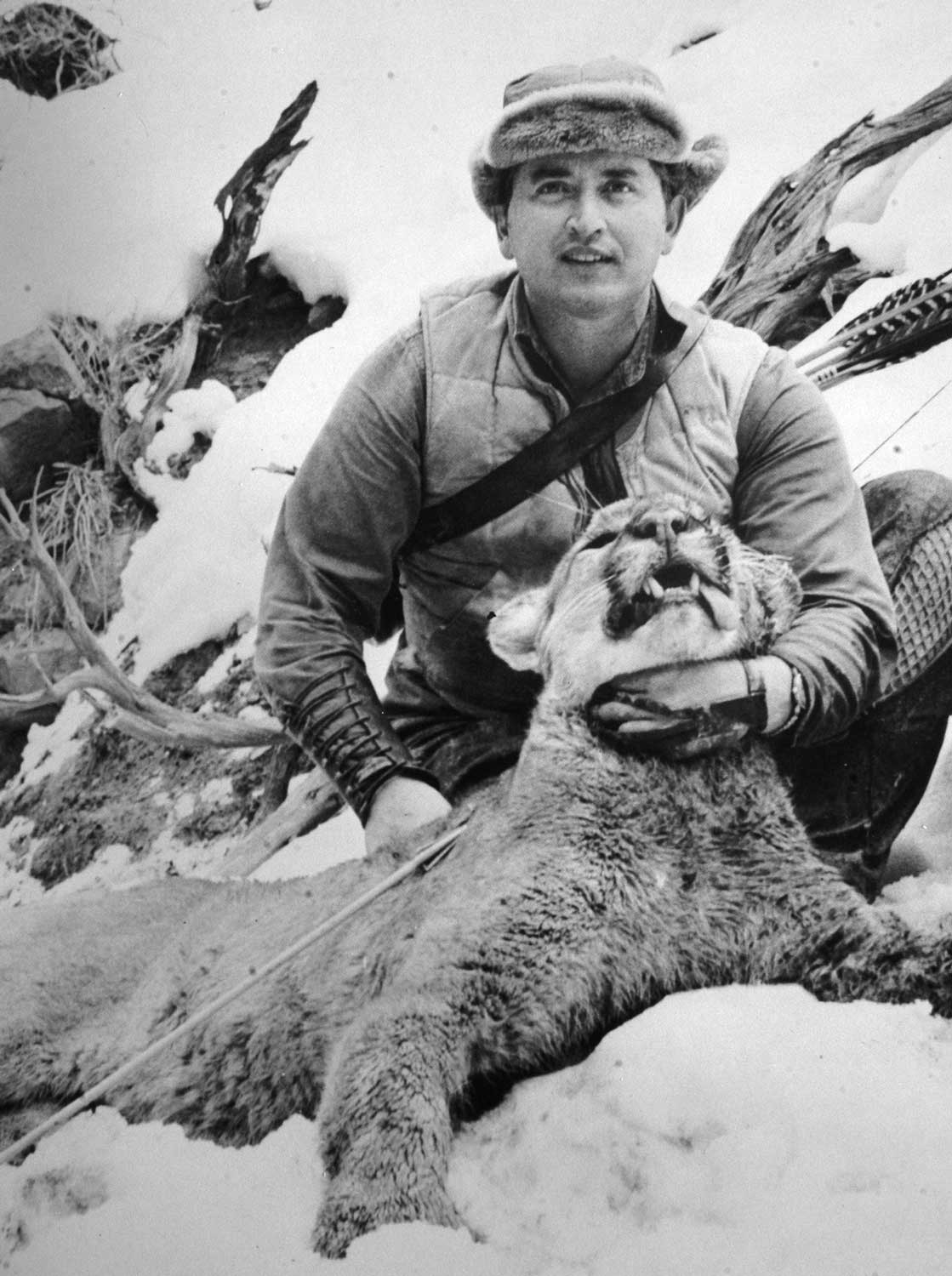

A grueling day in Colorado yielded difficult shots, two cougars. Swinehart arrowed one at 100 yards!

When Colorado outfitter Jack Peters telephoned one February morning to say he’d found a huge set of lion prints, Bob packed his hunting tackle and caught a flight that put him in Grand Junction early the next morning. Soon the men were post-holing crusted, knee-deep snow at 9,000 feet. “The going was as grueling and treacherous as any hunt I’ve ever made,” Bob recalled. The track joined another; then the pair split. The hounds treed the largest animal seven times before the exhausted hunters got within arrow range. Swinehart’s shaft tumbled the cat 30 feet into the snow. “But it rolled off the ledge [and] regained its footing…. In desperation I released an arrow from my high perch on the rim” as the animal trotted off 100 yards below. The broadhead’s lazy arc and the lion’s rail-smooth route seemed unlikely to meet. To the astonishment of both men, they did! The cat staggered and fell!

Such a climax would send many hunters to hot supper by the hearth. Not Bob Swinehart. Chilled, wet and weary, he and Peters retraced their tracks to trail the second lion. It took refuge in a cave, high on a bluff. There was no place from which to shoot except on a ledge at cave’s mouth. Bob’s first arrow into the darkness grazed the lion, which rocketed from its depths. Peters blocked the escape with a chunk of shale, but was almost knocked off the shelf by the impact. Bob’s next shaft buried itself in the cat’s chest.

Swinehart had more than his share of natural talent. Not only did he make difficult shots on hunts; in the off-season he nailed targets as demanding as tossed dimes in front of audiences. Asked to explain how he did that, he’d deadpan: “It’s up to the assistant. Just shoot and let him toss the dime in front of the arrow.” Like Hill, he shot fast and fluidly, bow and head canted. His routines included offbeat positions, even holding the bow with his feet. He advised hunters to practice from a variety of field positions.

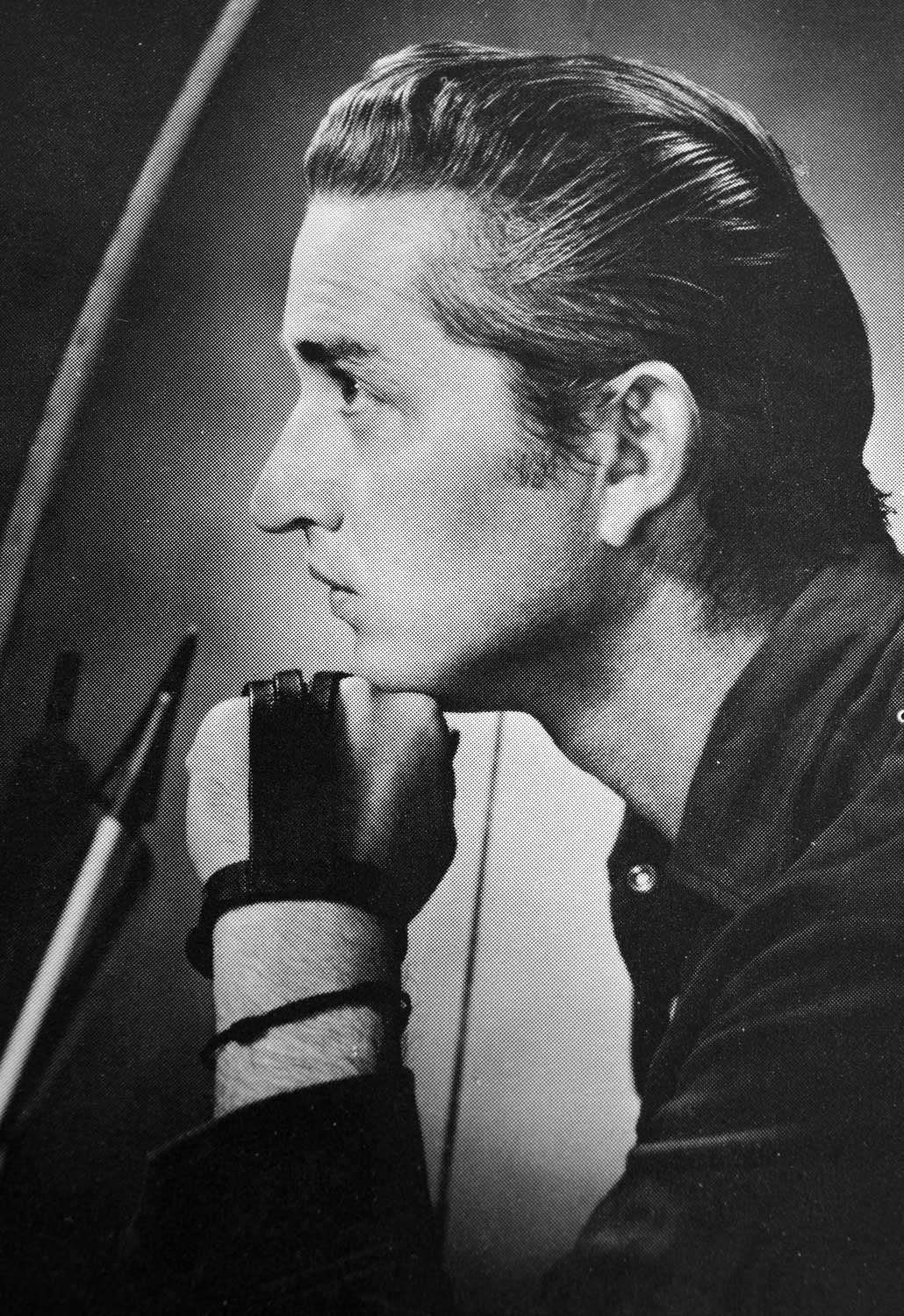

To keep his shooting form, Swinehart shot “an hour a day three times a week” during the summer and fall; but he laid off the bow for periods, too, “so as not to become stale.” At 5 feet 10 inches tall and 170 pounds, Swinehart was not a big man; he worked hard to stay fit enough to draw heavy bows and to help meet the challenges imposed by hunts in tough places. To others he recommended isometrics and “running several miles two or three times a week.”

In early post-war America, few archers had thought of hunting Africa’s heaviest animals with a bow. Hill’s much-publicized 1950 safari for elephant no doubt added a sense of urgency to Swinehart’s long-held dream to be the first archer to claim that continent’s “Big Five” with a longbow. Preparing for the task, Swinehart built himself up to handle bows of up to 110 pounds pull. (Hill had readied five bows for his safari, in draw weights of 65 to 115 pounds.) After fashioning special arrows up to 40 inches long and as heavy as 2,000 grains, Swinehart found that 36-inch, 1,200-grain arrows flew better and delivered adequate penetration. To reach that weight, he shaved solid-fiberglass fishing arrows to slip inside Micro-Flite shafts. Metal nocks of his design added heft and were open enough for the thick bowstrings. They also brooked the brutal forces imposed by the heavy arrow’s inertia under the thrust of a 110-pound bow.

Sagittarius takes readers not only to Africa, but back in time. The Luiana-Luengue Concession of Angola put Swinehart on the trail of Cape buffalo when the tab for a three-week hunt “including air fare, game licenses, safari costs…trophy care and shipping” might total $6,000 to $7,500. It also afforded him the chance to photograph people and places of an era now gone, and to pursue animals since protected.

When Swinehart hunted the black rhinoceros, it was already off-license throughout most of East Aftica. The few permits in southeast Angola were costly, he noted: $750. He applied and drew. It would be his second rhino hunt. He’d earned a shot on the first; but as the arrow bit, the animal spun and came. A hail of .458 bullets felled it short steps from Swinehart’s shoes. Not a bow-kill.

From Rui Almeida’s camp on the Luengue River, the two hunters probed the bush far upstream. When at last they spied a bull, Swinehart began a half-mile stalk through waist-high grass. Sun and wind favored him, and he closed to 25 yards. But before he could maneuver for a shot to the ribs, something alerted the bull. He charged. Bob sprinted toward a tree, where Rui was covering him. Two blasts from the .475 kicked sand in the rhino’s face. It stopped, then as if forgetting its mission, trotted off. Rui had gambled warning shots would suffice. He knew his client didn’t want to lose another rhino to a bullet!

Next morning after hours on a fresh track, they got within 15 yards of the rhino. Alas, Swinehart had no shot before the bull ran off. Miles farther along, after switching places with his lead tracker, Bob got the look he needed. But the rhino whirled as the shaft sped from the string, and it glanced off a horn. Confused, the beast paused just long enough for the bowman to nock, draw and release a second 1,200-grain arrow. It buried to the fletch behind the foreleg as the rhino crashed away. The hunters heard it fall.

“My bow handle is straight, and covered with rough leather.” This bow is the author’s, by John Schultz.

Swinehart’s intensity when closing for the shot prompted Howard Hill to say he “took too many risks.” Of Bob’s quest for the Big Five, Hill added, “I was confident he would accomplish the task, provided he did not get himself killed first.”

Oddly enough, one of Swinehart’s closest calls came when he had a rifle in hand.

In Mozambique on his fourth safari, his PH, Amilcar “Mike” Coelho, urged Bob to kill a “meat” buffalo with his .375. The animal fell to the shot. But when the hunters approached, it rose and charged. Bob leaped out of the way as his and Mike’s bullets pounded the bull without effect. The buffalo spun for another go “three or four yards away…. I fired from the hip, point blank, the muzzle practically touching [it.] The black hulk thumped to earth ….”

Shaken, Swinehart later demurred when an exceptional buffalo appeared. But Mike insisted he try for this bull with his bow: “You don’t see such buffalo every day!” Grass hid the hunters as they sneaked within 30 yards. Driven by Swinehart’s 90-pound bow, the broadhead knifed home. The bull thundered off, but came to a stop a short distance on. Seconds later it collapsed.

Another episode had nothing to do with the Big Five. Swinehart was ankle deep in soupy papyrus when he saw bubbles streak toward him. “I quickly drew an arrow and released,” he wrote. No carp shoot, this! The solid fiberglass shaft drove deep into the vitals of one of Africa’s most dangerous beasts. [“But] he was too close — just 18 inches from my feet. [He] would have had me if my guide had not…blasted a hole in the hippo’s brain.” He reported that in one area, 25 of 27 humans killed by big game over a short period were taken by hippos. Ever the naturalist, he added that a hippo has a six-bushel stomach and can remain under water for 10 minutes.

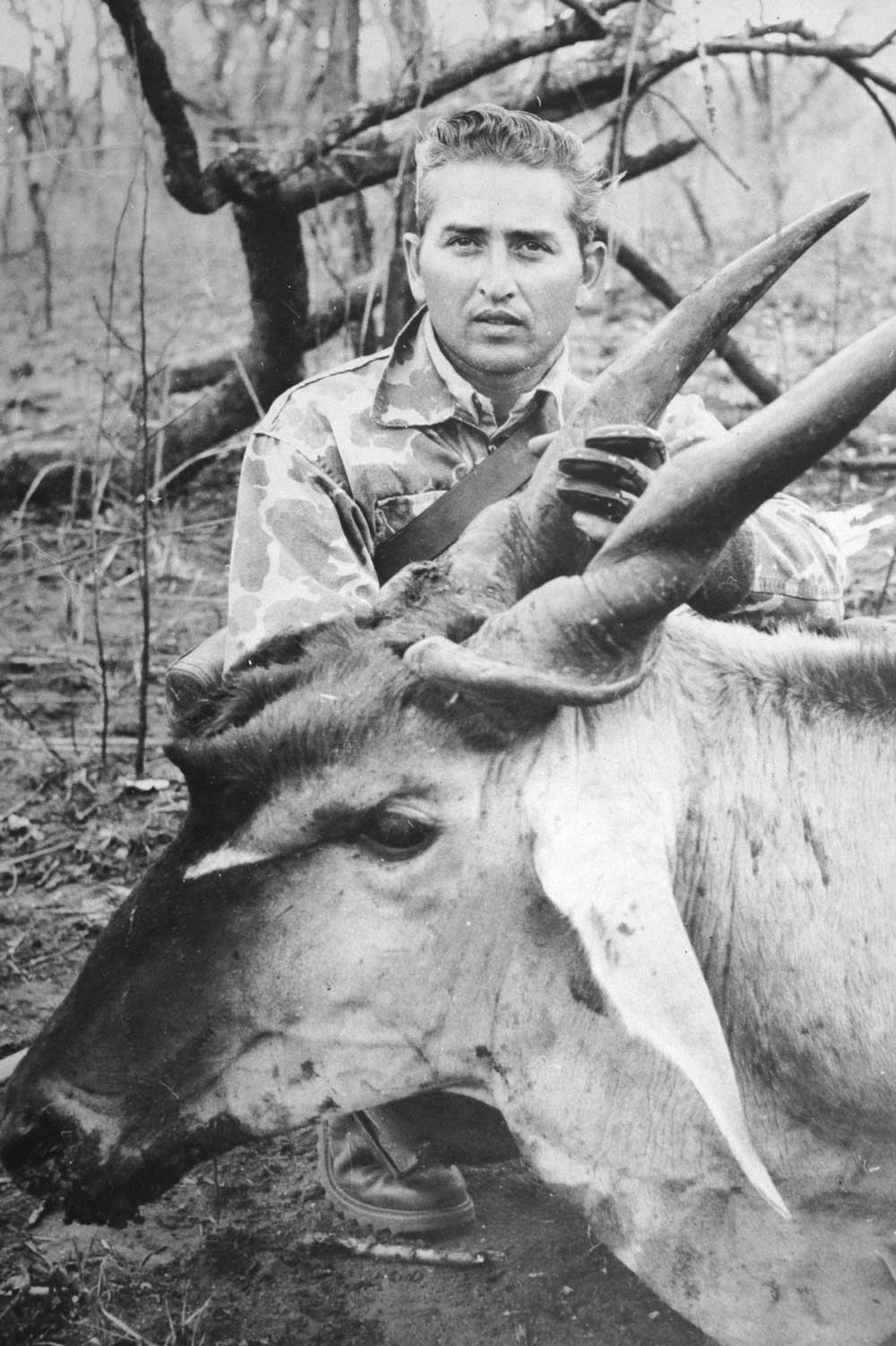

Several safaris brought Swinehart chances to hunt eland and other plains game as well as the Big Five.

Swinehart agreed with many professional hunters that the elephant is the most dangerous African game, and the most difficult for an archer to kill. The hide, well over an inch thick, “is the toughest of all skins. It resists cutting like pressboard….” On a hunt in Mozambique he succeeded in killing an elephant, but not with a single arrow. He would try again in Angola, whose elephants are famously huge. Would a 100-pound bow prove stout enough?

Not long into the hunt, Rui’s trackers found the prints of a giant bull. “My two boots, heel to toe, fit precisely in one footprint,” reported Swinehart. With another bull, it led the hunters on a long chase, interrupted by wind changes that nixed their efforts.

Hours later the pair of elephants had become five. At last the wind and terrain permitted Swinehart an approach. Just 22 yards from the biggest bull, all was going well. But this shot had to be perfect. He nocked an arrow — then gathered himself and dashed into the open to grab the very best shot angle. Too late the bull turned to flee. The shaft drove deep, spitting the heart. The elephant died as it ran and crashed to earth.

“Without extending tail or trunk,” Swinehart reported, the bull measured 16 feet in length and 12 feet in height. The tusks averaged 70 pounds.

In Mozambique’s central concession of Marromeu, Bob hunted with Mike Coelho, killing several of Africa’s signature antelopes. Sable, waterbuck, eland and bushbuck fell to his arrows. But to achieve his goal he would have to take the two great cats. His chance at a leopard came after days of waiting near bait hung in a tree. In evening’s shadow, a big tom appeared. A cautious pause, then, almost magically, the cat was high above. When he heard teeth tearing at the bait, Bob drew his 75-pound bow, a new Ben Pearson take-down recurve. The arrow zipped through the leopard’s chest and out the far ribs. Common sense and accepted practice dictated the hunters wait for daylight to follow. The cat lay dead 70 yards off.

Swinehart had hunted his way through four safaris without loosing a shaft at a lion. When he and Coelho started the Land Rover on a warm July 4th, they had no reason to expect better luck. Some miles out of camp, Mozambique mud mired the vehicle. As hunters and trackers struggled to extricate it, Bob noticed vultures circling a mile farther on. Retrieving the Rover, they motored to within a quarter mile of the carrion, then proceeded on foot. Suddenly Swinehart was eye-to-eye with a black-maned lion at 35 yards! Quickly he drew his longbow and released. The lion rocketed away; fletching bobbed on its ribs. Swinehart followed. In a gap in tall reeds, he again faced the cat, poised now as if to spring. “I sent another arrow into his chest…. He bit [that] shaft in two” and vanished. Nerves taut, the bowman inched ahead. When the reeds shivered, he sent three arrows to that spot, pell mell, then backed off. With Mike, he watched. After a long, silent stillness, they took the blood trail. The magnificent animal lay dead, the first arrow having pierced its heart.

Swinehart would visit Africa later on photo safaris. In Mozambique his 12-year-old son, Kurt, shot an impala with a rifle, the only kill he recorded on that trip. He noted that explaining the urge to hunt is difficult. “Hunting is a great many things. Killing happens to be a part of it….” Bowhunting had blessed him, he wrote, with much that had nothing to do with a kill. The raw challenge was compelling. Beyond that, it had given him “an understanding of nature and people, [and] my closest friends.”

Sagittarius is a window into the life and times of a man Howard Hill called “the best big game hunter I have had the pleasure of being with on the trail….” He applauded Bob’s skill with the bow, and his patience afield. “[He] is a fine tracker and possesses great courage.” In January of 2000, the archery industry would second Hill’s assessment, inducting Bob Swinehart into the Archery Hall of Fame.

Africa’s challenges proved less daunting than those in Pennsylvania. In 1972 Swinehart and his wife divorced. For two more years he retained ownership of the construction company once held by his father-in-law. According to the Morning Call newspaper, Bob worked later in Ohio for Asplundh Tree Experts. Then he returned to his native Pottstown, where again he would appear in the Morning Call.

On May 13, 1982, the paper reported Robert N. Swinehart, age 54, had taken his own life with his hunting rifle. He’d been troubled, speculated some, after his brother David was bludgeoned to death a few months earlier outside Pottstown. No other reason was given.

Whatever his struggles, the most dangerous game on earth was no match for this determined man and his bamboo stick.

This article originally appeared in the 2021 Guns & Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

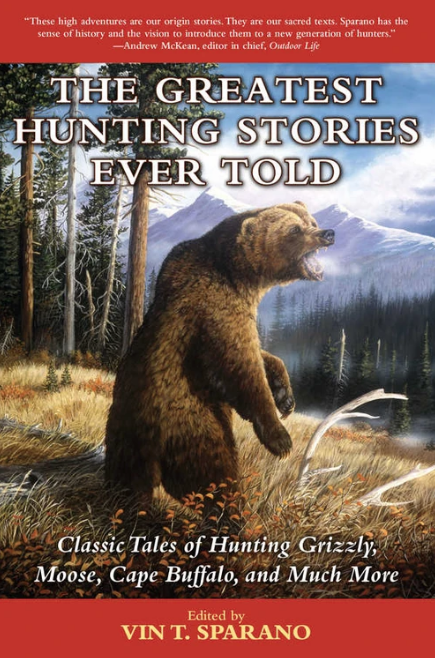

The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Buy Now

The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Buy Now