The unlikely life, art and death of legendary artist and adventurer Peter Beard.

Peter Beard was a hard man to peg. A photographer of wildlife and beautiful women, a writer, an ethnologist, explorer, hunter, naturalist, conservationist, ladies man, married man, wise man. Good work if you can get it. But if you’ve ever seen the video of him being trampled by an elephant, you might want to add “fool” to that considerable list. But however you cut it, you’ll run dry of adjectives long before you ever had Peter Beard nailed down.

That he lived as long as he did is a God’s Wonder. He was cracking jokes when they funneled him into the safari car, though he was not joking by the time the bush plane finally got him to Nairobi. His insides were sloshing and he was declared “clinically dead” – but he wasn’t. A good thing.

Peter Hill Beard was the great-grandson of the legendary J. J. Hill, “The Empire Builder,” who spanned the continent with the Great Northern Railway back in 1893. Some called Old J. J. a Robber Baron and maybe he was. He also owned steamboats and coal mines, built a grand mansion in St. Paul, and funded construction of the city’s spectacular cathedral. But he’d get dirty if he had to.

A one-eyed, hard-bitten Canadian immigrant, J. J. surveyed sections of the route across the Great Plains himself – by dogsled. After two weeks on the trail, the story goes, he smelled more like his dogs than his dogs did. Refused lodging at a North Dakota hotel, Hill rerouted the rails 40 miles to the south, leaving the offending hotel landlocked and bankrupt.

Then there’s Hill City, Minnesota, The Empire Builder Amtrak run out to Seattle, and also a bar in Fargo, North Dakota, of the same name, where they proudly advertise you “limp in, leap out.”

On the other side of Peter’s family was his step-grandfather – tobacco magnate Pierre Lorillard IV. Fabulously wealthy, Pierre IV was also a real-estate developer, philanthropist, world traveler, yachtsman and horse breeder whose thoroughbreds placed in the Derby, won Belmont and cleaned up all over Europe.

On the other side of Peter’s family was his step-grandfather – tobacco magnate Pierre Lorillard IV. Fabulously wealthy, Pierre IV was also a real-estate developer, philanthropist, world traveler, yachtsman and horse breeder whose thoroughbreds placed in the Derby, won Belmont and cleaned up all over Europe.

Some say Pierre IV invented the tuxedo, but detractors claim he was only the first American to wear one in New York – after stealing the design from the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII of England.

Small wonder Peter Beard sported such a long and confusing resume.

Growing up among New York’s elite, Young Peter was a precocious child. By age 12 he was keeping diaries and taking photographs, combining them into handmade collage scrapbooks. A nice hobby, his family reckoned, while they made plans to send him to Yale Medical School.

Blessed with a keen eye and steady hand, Peter Beard might have made a fine surgeon, had it not been for Karen Blixen.

Karen Blixen, aka Isak Dinesen, was author of Out of Africa, eventually the heart-throb movie of the same name. But this was long before Robert Redford and Meryl Streep got hold of it. Beard went to Kenya in 1955 and again in 1960, and another J. J. Hill great-grandson, Jerome, arranged the introduction. By that time Blixen had retired to her native Denmark, but the two struck up a letter-writing campaign after their first meeting.

Beard was smitten with Blixen “who in her life and person sums up the old Africa, lost beyond excavation…an unseen support for me, a figure of real and poetic importance for the world.”

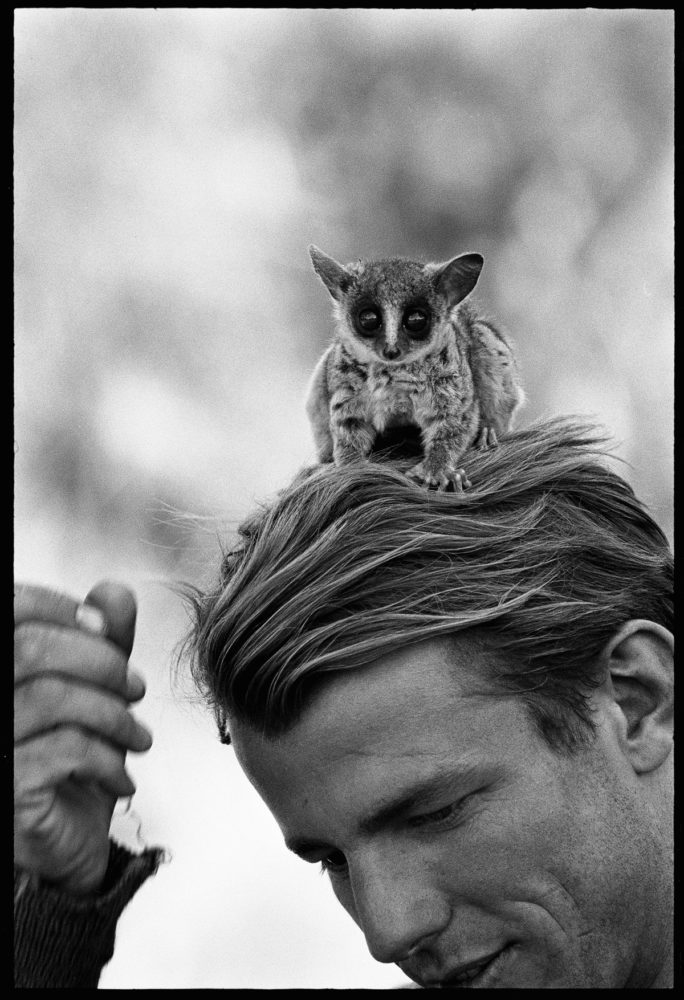

Peter Beard purchased 45 acres adjoining Blixen’s coffee plantation. He pitched a tent and called it Hog Ranch, for the abundance of warthogs thereabouts. Beard befriended Blixen’s old cook, Kamante, and moved him onto his property. He also fed the warthogs until they were entirely tame.

“It was amazing to discover this otherworldly world where the laws were very old and common sense still a strong ingredient…where survival wasn’t just an expression,” Peter wrote. Indeed.

Those Hog Ranch warthogs may have become acclimated to people, but not to each other. One afternoon a battle-royal between two dominant boars flattened tents, upended tables and sent camp staff scurrying from the snorting and slashing melee.

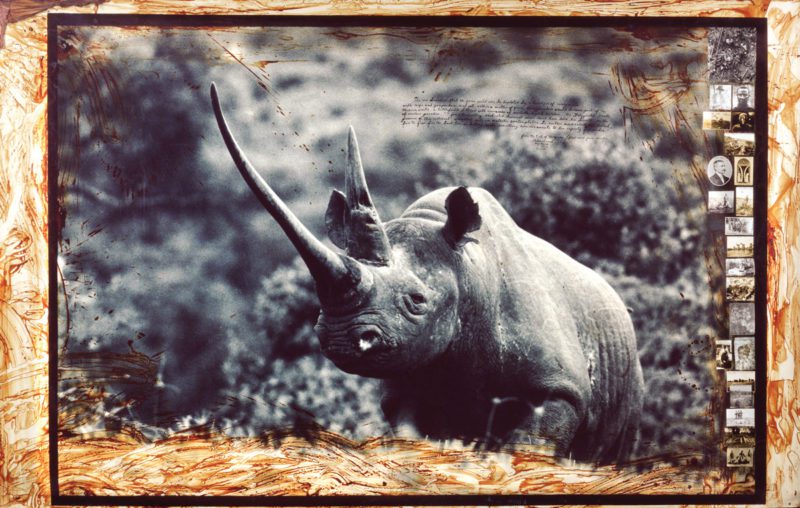

Peter Beard lost interest in medicine when he came to the conclusion that “humans are the major disease.” He completed a major in art history and upon graduation, he ran off to Kenya where in 1955 he joined an expedition to rope and transport white rhinos from overpopulated areas near Tsavo National Park.

Beard, who could turn a phrase as deftly as a camera lens, began his tale this way: “Farther down in Zululand, Umfololzi’s park warden was constantly talking about having too many of an animal that was far too rare . . . . one moonlight night on an open plain, he saw sixty-four white rhinos standing together in the silvery glow – a horny mob scene under the full moon.”

After a mountain of paperwork secured the necessary permits, Beard and his cohorts went to work. “My first and most favorite job in Africa,” he says. “We were Gardeners of Eden.”

Well, not quite. Men and beasts wore each other out. There were any number of predictable escapades – wrecked cars, gorings, tramplings – and unpredictable ones as well, like when a candy-chomping baby rhino clipped a finger off a game scout who did not get his hand away in time.

After four or five months of chaotic bush rodeos, some of the rhinos began to look familiar. The beasts had turned right around and come home! But no matter, the trapping and transporting went on. Meanwhile, back in Nairobi, government officials cashed their paychecks and called the project a resounding success from the number of rhinos “relocated.”

Rhino roping – “conservation at its loony best” – was formative for Beard, who came to believe that protecting game from native and sport hunters was leading to overpopulation and eventual starvation for many wild species.

Rhino roping – “conservation at its loony best” – was formative for Beard, who came to believe that protecting game from native and sport hunters was leading to overpopulation and eventual starvation for many wild species.

Nowhere was that more evident than in Tsavo National Park where some 50,000 elephants were eating themselves out of existence. Beard went to “Starvo,” as he called it, in 1961 to photograph the disaster. His first book, the fantastic The End of the Game, was the result.

Deeply disturbing and politically incorrect, The End of the Game is a riveting mix of Peter’s photography, native art and Blixen’s vintage photos with quotes from just about everybody who has written about Africa, from Greek historian Pliny the Elder (“there is always something new and strange out of Africa”) to Colonel J. H. Patterson, the man who hunted down the man-eating lions that stopped the construction of the “Lunatic Line,” the Uganda Railway back in 1898.

The End of the Game was reprinted by Taschen Publishing, but years ago when originally released, the book was quietly removed from many public and school libraries. Little boys, it seems, swooned over Beard’s celebration of bare-breasted African women and little girls wept at photos of dead and starving elephants. Today, if you are lucky enough to find a first-edition copy, it might be a discard from the Orange County Public Schools, spirited away from the incinerator and lovingly shipped from a used book dealer in London.

When “60 Minutes” ran the dead elephants story and blamed it on poachers, Beard hand-delivered a letter of protest to the CBS New York corporate office. His letter was “misplaced” and never acknowledged. But all that was awhile in coming. Meanwhile, Peter Beard was off chasing crocodiles.

The Government of Kenya was considering legalizing croc-hunting, but it needed some numbers first – population, lengths, girths and weights, life expectancy, reproduction rates, and so forth. For this study, they were willing to allow a private contractor to kill an astounding 500 crocodiles for their skins – meat, too, if they could stomach it – so long as appropriate data was collected in the process.

Beard threw in with Alistair Graham, formerly a zoologist with the Game Department, and then an operator of his own research firm. The pair flew a bush plane in to Lake Rudolph, crocodile central.

Lake Rudolph – now Lake Turkana – is square in the middle of the infamous Northwest District along the Somali border, home to nomadic tribesmen, scorpions, puff adders, scruffy lions and scruffier shifta bandits who will rob you and then skin you alive just for fun. A volcanic island rises from the alkaline waters, still smoldering from subterranean fires. It was a “difficult place, awkward to get to, uncomfortable when reached, dangerous when meddled with,” noted Graham.

Beard and Graham set up camp on a gravel beach, in a desolate and windblown bay called Ferguson’s Gulf, wryly wondering what sort of man Ferguson was and how such a place had come to be named for him. They employed Turkana skinners and porters, and set about their grim work of shooting 500 crocodiles. The work was grim indeed, and as dangerous as you might expect. Graham and Beard set a quota of 50 crocs a month.

Though previously unhunted, the beasts were extremely wary. They might lay in full view while sunning themselves on shore, but they would ease into the safety of deep water at first sight of the hunters.

Sometimes the men hunted at night, putting the crosshairs squarely between the eyes shining red and yellow in the flashlight beam. Daytimes, they would disguise themselves as crocodiles, greasing themselves with lake mud and slipping along behind a blind of inner-tubes and vegetation to get within range.

Sometimes the men hunted at night, putting the crosshairs squarely between the eyes shining red and yellow in the flashlight beam. Daytimes, they would disguise themselves as crocodiles, greasing themselves with lake mud and slipping along behind a blind of inner-tubes and vegetation to get within range.

Like all reptiles, even when fatally hit, the crocs would not obligingly die on the spot, but would flip and roll into deep water, necessitating a harrowing retrieve. Beard’s casual attitude toward obvious dangers reinforced the Turkana’s suspicions that all white men were crazy.

A year on the lake and just three crocs short, the men chanced a long boat ride when they should not have. They got their crocs but were overturned in a sudden squall, and when they finally staggered ashore minus the skins, they were happy enough to call 497 a generous plenty.

Eyelids of Morning was the result. As in The End of the Game, Beard and co-author Graham did not speak only of their adventures among the crocodiles and Turkana, but wove their experiences into all of human history.

The book’s subtitle speaks of “the mingled destinies of crocodiles and men.” Sometimes it seems more like “mangled destinies,” especially considering the almost-phony shot of Beard writing in his journal from the jaws of freshly killed croc. The croc may have been dead, but just as he went into rigor mortis, its jaws tightened and the Turkana had to painfully extract Beard from the toothy maw.

And then there is a horrific photo of something not phony at all – the arms and legs of an unwary Peace Corps volunteer who swam where he should not have been swimming.

Back in civilization, Beard considered his next adventure. His choice must have seemed an obvious one. Why not go on tour with the Rolling Stones?

What?

Well, why not? After all, he knew Mick Jagger and Truman Capote from his New York days. Mick would be the subject, Beard would take photographs, and Capote would write the text for a large format book called It Shall Soon be Here.

If you know anything about the Rolling Stones, you will probably recollect their infamous 1972 tour, coinciding with the release of their landmark album “Exile on Main Street.” After hundreds of arrests, a half-dozen riots and a bombing, the Stones were indeed exiles on main street, and just about everywhere else. Capote jumped ship when the band took to packing pistols and “It Shall Soon be Here” was abandoned.

To Peter Beard, Africa never looked so good. Back in Nairobi, a graceful brown girl caught his eye. Beard introduced himself, then snapped some photos, which he sent off to a New York modeling agency. “Who is this girl?” they wanted to know. She was Iman Abdulmajid, a university student and daughter of the Somali ambassador to Saudi Arabia. Abdulmajid went on to become the famous Iman, a super-model and one of the most recognizable and photographed black women in the world.

And Peter Beard went on to a new career, photographing beautiful women in exotic settings for the most prestigious fashion magazines. Beard would marry model Minnie Cushing and then actress Cheryl Teigs. His last wife, Nejma Khanum, is likely the best-looking woman to ever come out of Afghanistan. They had a daughter, Zara, which means Yellow Desert Flower in Arabic. Zara was inspiration for Beard’s next book, Zara’s Tales, stories he does not want her – or us – to ever forget.

And Peter Beard went on to a new career, photographing beautiful women in exotic settings for the most prestigious fashion magazines. Beard would marry model Minnie Cushing and then actress Cheryl Teigs. His last wife, Nejma Khanum, is likely the best-looking woman to ever come out of Afghanistan. They had a daughter, Zara, which means Yellow Desert Flower in Arabic. Zara was inspiration for Beard’s next book, Zara’s Tales, stories he does not want her – or us – to ever forget.

Beard also published two high-end art books of his creations, both limited editions, numbered and signed by the artist. If you want to ask what a copy might cost, you don’t really need to know. The same holds true for his photographic prints, each an original of his own design that might be framed with doodlings from native artists, crisscrossed with Land Rover tire tracks with his own blood serving as ink for the images. Some of these wildly original renditions have fetched as much as $300,000.

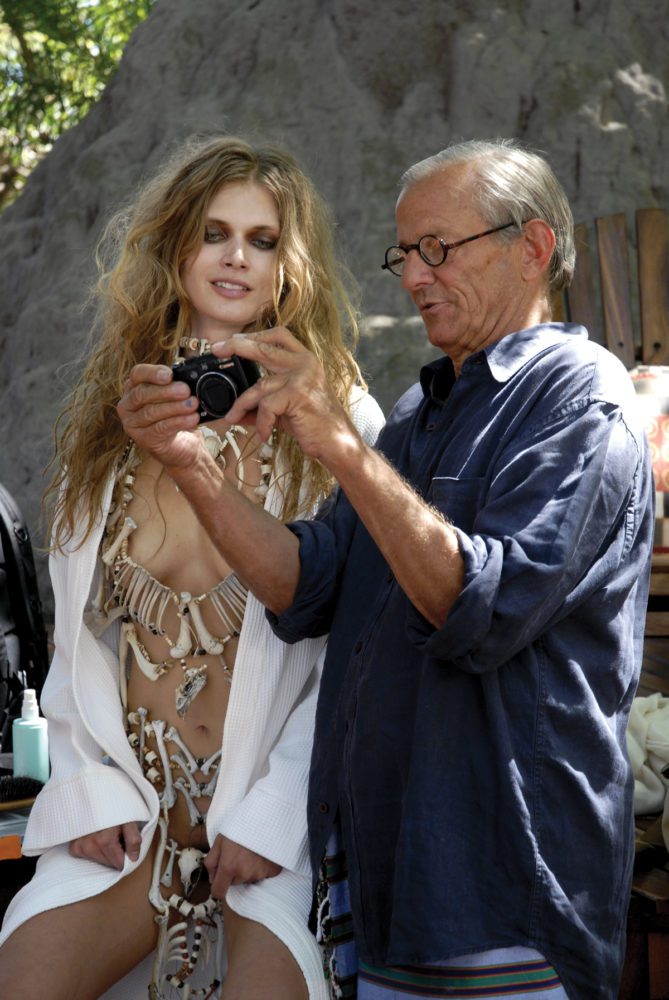

And then comes the 2009 Pirelli Calendar, a limited-edition publication by the tire company of the same name. Famous enough for a cult status of its own and known to the art world as simply “The Cal,” it was only a matter of time before Peter Beard was invited to shoot it.

All of the images were taken in May at an eco-camp in Botswana, “a wild and beautiful country,” said Pirelli’s communications manager Julie Naylor, “completely unspoiled…a most exciting project with Peter’s exuberance and energy shining through.”

Good stuff, Peter Beard, very good indeed. Your grand-daddies would have been mighty proud. Ease your broken bones, all pinned back together. Thank you for your stories and taking your pictures.

Peter Beard, age 82, disappeared on March 31, 2020. After a 19-day search, East Hampton Town police released a statement confirming Beard’s death after discovering his body in Camp Hero State Park in Montauk about one mile from his home. The statement also claimed, “Peter defined what it means to be open: open to new ideas, new encounters, new people, new ways of living and being. Always insatiably curious, he pursued his passions without restraints and perceived reality through a unique lens.”

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Sporting Classics has compiled this remarkable anthology showcasing the best African adventures published in our award-winning magazine.

Ruark, Capstick, Roosevelt, Markham – the legends in outdoor literature are all here, sharing their stories of deadly encounters with dangerous game, of bizarre run-ins with witch doctors, gorillas and man-eaters, of safaris into the uncharted wilds of deepest Africa.

Illustrated by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now