Perhaps there truly are angels among us.

The journey to the mailbox should have been exciting. There was a flawless, expectant stillness to the air, as if the world held its breath in waiting. Dense, leaden clouds layered the bottom of an ashen sky, leaving the fields gaunt and drawn in the penetrating chill, the woods and thickets huddled and lonely. Sparrows and juncos anxiously worked the fencerows, bunching and foraging with frenzied urgency. Absent the usual malediction, a line of crows lugged slowly by. It was compelling, unmistakable … the promise of snowfall.

But the memory was too fresh. He would have loved this day, for there were only a few such in any year, even more rarely at the tag end of February. The birds would move. Always before snow or ice, the birds would move.

The mail was uninspiring. She turned and started for the house, undeterred from the mood of the moment. Uncle Murray had been intrinsic in her life. He and Mary had no natural children of their own, but the fascinations of their antiquated, country lifestyle were irresistible to two generations of nieces and nephews. Never beleaguered by social convention, the veneer of their existence betrayed the culture and fervor of their lives. The barn and outbuildings, ancient and drab, stood around doubtfully on splayed legs. The same turn-of-the-century farmhouse was their home for 78 years. From the outside, it would have appeared plebeian, even unkept. For at least half that time, it had worn the tattered remnants of its maiden coat of paint. But inside was a wealth of period music, antiques, books and oils that would have been the obelisk of any elitist townhouse. And out back was a neatly kept kennel with running water and a sewage lagoon. It was a reflection of their simple creed . .. passion without pretense. The old house weathered the storms on its own terms, gracefully, as they did.

Murray Britt had made special of her from the beginning. From the time he took her and her third birthday frock into a barn-stall full of marauding, seven-week July pups, he had won her heart. It was her first lesson of many, from him on what was most important in life. Forever an outdoorsman and dog man, he kept ranks of pointing dogs and legions of hounds. For all the years of her childhood and even after she was grown with family, he would show up on an anonymous impulse with a box-full of dogs and an invitation to go a-huntin’, totally oblivious to the possibility that anything in life could be more important to the moment. More often than not, it wasn’t. She could mark the memorable events of their relationship by epochs of dogs … by Jake, Sadie, Belle, Pat or Gabe. As he habitually remarked, “If it hadn’ got a dog in it, I never cared much for it.” Most of all he cared for pointing dogs and quail hunts.

She snugged her coat to her neck, taken with a sudden awareness that the chill was growing. It was then, also, that she became conscious of the crunch of gravel under tire rubber at the end of the drive. The car was unfamiliar, an older, generic sedan that had once been a more virtuous blue. It was proceeding up the drive and she stopped to wait, slightly ill at ease. As it neared, it appeared that the driver was the only passenger, an older man with white hair. She began to relax.

“Pardon me, miss, would you by chance be Nida Giddens?” he inquired, as he pulled alongside. His face was gentle, his countenance comforting.

“Yes …” she responded, cautiously intrigued at her spoken name, “can I help you?”

“Please forgive the imposition, but I wonder if we might talk for a few minutes.”

He climbed out of the car, and steadied himself with the assistance of a cane. “Arthritis, the doctors say,” he commented, answering the unspoken question, “an abomination of age, I’m afraid.” He wore khaki trousers, a frayed-at-the-fringes, cinnamon sport coat of corduroy that contrasted pleasingly with the sterling tones of his hair and mustache, and lacerated hunting boots with leached toes. She liked him immediately.

“I’m Frank Gupton.” He extended a hand, and an affable smile. She accepted both.

“I’m sure you don’t know me, but I hope you will come to forgive my intrusion. We can sit in the car if you like,” he gestured, “but it’s all the same to you, I’d as soon sit by the fence and enjoy the day.”

“Yes, thanks,” she replied, “I would prefer that.” She led the way to a nearby fence corner with a comfortable bench of earth, her curiosity rising.

“What would you like to talk with me about?” The stillness punctuated the question.

“Bird hunting, actually,” he smiled.

“Bird hunting’??”

“Yes, I have gathered that subject is not unfamiliar to you. Do you mind if I call you Nida?”

“No … I mean yes, please.” “Bird hunting!?,” she was repeating to herself silently, incredulously.

“Do you know the significance of today,” he asked.

“No.” More than you know … she had started to say.

“It’s the last day of the quail season. And could you ever find a better one?”

“No, it’s virtually perfect,” she agreed.

“As perfect as it is, there is another, even more special to me. Fifteen years ago. I was a bit younger and sprier then, still kicking up a little dust. Red was still here … a lifelong friend. We both kept dogs and bird-hunted. We loved it more than anything.

“Fifteen years ago almost to the day, the bird season had wound down to the last Saturday. We had about worn our local territory out by then, and were up for a change of scenery. Somebody had told Red about a laid-back crossroads two counties south that was thick with quail, so we loaded up the guns and the dogs and were on the way about 4:30 in the morning, excited as schoolboys with a substitute teacher.”

“It was a beautiful day for February, which usually goes limp and balmy on its gasping breath. Different from today, but nice nonetheless. The morning dawned bright and yellow over a heavy frost, and when the first rays of the sun hit the tops of the pines the highlights in the ice looked like Christmas candles. The weatherman was promising light winds, and afternoon temperatures that would never get out of the forties. It was all ahead of us … bittersweet though, being the last day and all … and we were feeling mellow. Just as the sun climbed high enough to put a halo around the field edges, with the land still mostly in shadows, and all those fires in the frost, my old hunting buddy Red looked out the car window and said, ‘Don’t want anything more than this . . . never wanted anything more.’ I’ll never forget that. We never said a lot to each other. Wasn’t necessary.”

“It was a beautiful day for February, which usually goes limp and balmy on its gasping breath. Different from today, but nice nonetheless. The morning dawned bright and yellow over a heavy frost, and when the first rays of the sun hit the tops of the pines the highlights in the ice looked like Christmas candles. The weatherman was promising light winds, and afternoon temperatures that would never get out of the forties. It was all ahead of us … bittersweet though, being the last day and all … and we were feeling mellow. Just as the sun climbed high enough to put a halo around the field edges, with the land still mostly in shadows, and all those fires in the frost, my old hunting buddy Red looked out the car window and said, ‘Don’t want anything more than this . . . never wanted anything more.’ I’ll never forget that. We never said a lot to each other. Wasn’t necessary.”

His tale was warming nicely. Yet, she fought the urge to ask him why on earth he had arrived out of nowhere to tell it. Why to her? But the lull and tenor of the old man’s voice was captivating, and an interruption would have been unsouthern.

“The country turned out to be everything we had hoped for,” he continued. “Very few houses. Laid-out bean fields everywhere, patches of scrub lespedeza … briery heads in old grown-up weed fields, brooms edge here and there. Now and then there was an old garden plot gone to seed, an abandoned hog lot, or a cast-off tobacco bed. You could read quail into every nook and cranny of it.

“It was like that everywhere when I was growing up,” Nida observed spontaneously.

The old man paused and pulled two sticks of horehound candy from his coat pocket. She smiled. It had been a longtime since she had seen horehound candy.

“Care for a piece,” he offered.

“Yes, thanks.”

They pulled silently on the candy for a minute or so. The chill was growing ever more convincing under the somber sky, the air dampening as the afternoon waned. It would start soon.

“Did it turn out as well as you hoped,” she asked.

“Yes,” he said gently.

“We rode around awhile admiring the territory until we found an inviting field with no poster signs. We weren’t in the habit of hunting without permission, but there wasn’t a house anywhere close to go ask, and we were so excited over the prospects, we decided to go ahead. It didn’t sit well though and before we got halfway across the field, we decided to gather up the dogs and find somebody to ask. It wasn’t easy; the dogs were full of vinegar and in no mood to get back in the box, but we finally rounded ’em up and leased ’em. We had almost made it back to our car when an old, beat-up, green pickup came by, slowed down like it was going to stop, and then went on. In a couple of minutes, it came back.

“‘Red,’ I said, ‘we’re in for a chewing,’ as the old truck pulled up and stopped. It had gouges in every fender, the paint was flaking off in spots, hanging like loose bark on a sycamore tree, and it kept running for fifteen seconds after the switch was killed. Red looked at me wall-eyed.

“The driver got out and looked at us. He was middle-aged and in farming garb, two days’ worth of stubble on his chin, obviously a local. Where you boys from?,’ he asked. No show of emotion either way.

“Red took all kinds of pains telling him and begging the situation. I thought he was doing pretty good, so I just kept my mouth shut and tried to look genuinely pitiful and repentant. About halfway through Red’s apologetic diatribe, the man’s face began to lighten a bit around the corners, and Red, sensing progress, turned it on all the more.

“Finally, the guy interrupted. ‘Listen,’ he said, smiling for the first time, ‘why don’t you boys just load your dogs in the back and go hunting with me.’

“I looked at Red in complete disbelief. He had a strange grin on his face like he had one foot in Heaven and a promise for the other.”

“I guess so,” Nida said, laughing, now fully invested in the story. “You went, I guess?”

“Wasn’t a minute’s debate. We generally hung pretty tight to ourselves, but this man had a way, and no doubt knew the country and everybody in it. He introduced himself, we shook hands all around, and started loading guns and dogs into that old truck. We had three pointers, Pete, Bell, and Duke, pretty good dogs! But Bell hated to back, and would steal a point when you weren’t watching. We didn’t know what to expect dog-wise from our host, but wanted to be on our best behavior, so we left Bell in the box. We climbed into what was left of the front seat, me in the middle with the floor shift and an old Fox Model B between my legs, and rode a mile or two down the road. Red was beside himself, talking more than he had for the past three years.

“When we got to the first field we were going to hunt and turned out, eight bird dogs got out of the box! Or seven anyway. One was a question mark. He had four of the biggest, raw-boned, double-nosed pointer dogs we had ever seen, a strapping lemon-and-white pup on a check cord, and one small bitch that could almost have passed for a rabbit or a deer hound. That little dog could cover more ground than any dog I have ever seen, before or since. In polite company, she would have been liver-and-white, but the liver was more of a washed-out brown and the white was a sort of tobacco-stain yellow. She blended with the cover so well you could barely see her, so he ran her with a bell around her neck.

“Oh, what a morning it was. Clear and still, with a bite in the air … patches of frost still splattered around. We hadn’t been down twenty minutes, when the little bitch pointed. She was flying down a long edge when she smelled those birds and swapped ends like her nose was nailed to a wall. She took two mincing steps and snapped into a point … and left skid marks in the dirt where her toenails dug in. God, it was nice. The covey had fed about 40 yards into bean field stubble and she was reading them the bill of rights.

“I had followed bird dogs for 38 years, but the next few moments were easily the most moving of my hunting life. The sun was hard in our back, 9:30 high, in that forever blue, crystal sky, and the light reached over our shoulders and cut that little bitch out of her ground shadow like a carving relieved from a block of yellow fieldstone. Seven other dogs arrived on the scene from five different directions, all in turn, and caved at the withers like they had been cleaved, honoring the find. The pup was last up and a peaceable “whoa” was all it took. They ended up in a semi-circle, eight dogs! The intensity was electrifying. It was eloquent. Breathtakingly eloquent.”

“I would loved to have seen it,” Nida offered, tears welling. “Once, I hunted with my uncle and we had five dogs standing. It’s mesmerizing. You want to lock the moment away and relish it forever. It’s like a Christmas present in special paper with something wonderful inside, but too pretty to unwrap.”

“We savor ed it for quite a while before we kicked the birds up. When they went out, Red killed two, I got one, and the fellow we were hunting with knocked down three’ It went that way, more or less, most of the way. We called it quits about mid-afternoon with 16 birds in the bag. We thanked our benefactor profusely, this man who had been a virtual stranger only a few hours before. Whatever we said, it was totally inadequate. The conversation home that night was the best Red and I ever had. For the first time we tried to tell each other how much the years between us had meant, to relive a lot of the wonderful times we had enjoyed outdoors.”

For the second and last time, Frank Gupton paused in his account and looked away for long moments across the shadowy landscape. Waiting mutely, Nida Giddens respected his silence. His story was beautiful, but there remained a question in her mind. Finally, he turned and looked at her with softened eyes.

“Nida, we hunted that day near the little community of Turkey in Sampson County. The man we hunted with, who so generously gave us that exquisite, final day of the bird season 15 years ago, was your uncle, Murray Britt. He was the finest hunter and quail shot I have ever had the privilege of associating with. Red felt the same way. To this day, when someone mentions sportsmanship, I tell them about that day, and Murray Britt.

“I read his obituary in the paper in December. He died just three months after Red. The family note mentioned a niece, Nida Giddens, of Creedmoor. I live in Oxford, near the Brasstown Road. When I saw it, I knew I had to come and see you. I don’t know how much longer I’ll be here; it was a way of thanking him again, one last time. I asked around and found out where you lived. I purposely waited until today to come, so it would be an anniversary of sorts. I thought you would want to hear it. I hope I haven’t upset you too badly. I wish I could say I ordered the day; it seems made for the purpose. Makes you wonder.”

Nida Giddens was struggling to compose herself, trying to speak through the constriction in her throat and the tears in her eyes, and the mixture of pain and gratitude in her heart. He took her hand. “Call me some time,” he said softly, as he rose to leave. She tightened her grip on his hand, speaking a profound “thank you” with her eyes. The gravel whispered under the tires again and he was gone.

For a long time, she sat and stared into the eternal gray of the sky, trying to comprehend the magnitude of the day. How could it have possibly happened as it had? It defied reason. But the years had imparted the wisdom to leave it be, to accept it for the simple blessing it was. Perhaps there truly are angels among us.

The little bitch would have been Belle. She became as much of a legend in her time as her uncle in his. She, herself, would have been 30-something then, endeavoring to weave a teaching career between the assiduous threads of family responsibilities in a different corner of the world. Her uncle would have already been well into his 50s. She thought about the time which had transpired since, and his passing, reminded acutely of their revocable velocity of the years.

“The puppy on the check cord would have been Luke or maybe Joe,” she thought, as she gathered herself and started for the house once more. It was his trademark, a puppy on a check cord. So it must always be with men who set their worth by the measure of their dogs, find a passageway to tomorrow in faithful, hazel eyes, and wrap their memories in eras that hasten by on canine feet.

“The puppy on the check cord would have been Luke or maybe Joe,” she thought, as she gathered herself and started for the house once more. It was his trademark, a puppy on a check cord. So it must always be with men who set their worth by the measure of their dogs, find a passageway to tomorrow in faithful, hazel eyes, and wrap their memories in eras that hasten by on canine feet.

Almost as an illusion, the first notion of snow was on the air … tiny, vagabond flakes faintly stealing by, caught against the cathedral green of the pines … their faint ticking against the tinder leaves a welcome intimation.

Dusk was near. She could hear the clamor of the dogs at the kennel. Jarrod must be feeding. He was 15 now. Almost off the check cord.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1996 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

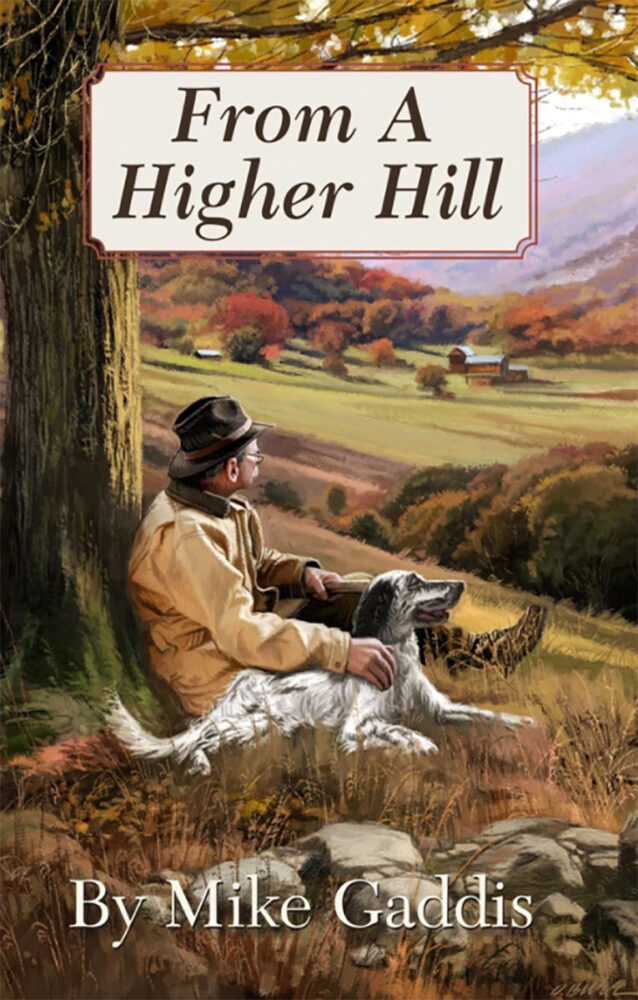

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now