There was urgency in his voice. My grandfather and Ed Brower went below deck. The Dolphin’s bilge pump had stopped working. Water was coming in.

It’s a bright Saturday afternoon in Fairfield, Connecticut, just after 5:00; mid-April 1960. Daffodils bloom along the edges of our yard. I’m sitting on the back porch steps as my grandfather, Jarvis DePledge, drives slowly up the driveway and stops in front of the garage. DePledge Plumbing and Heating is displayed with his phone number on the back windows of his blue station wagon. He and my brother Larry get out.

My grandfather’s hawkish face is tanned. His thinning hair is silver and black on top, white at the sideburns. The tailgate squeaks when Jarvis lowers it. He takes out two bushel baskets, walks across the lawn, puts them on the weathered top of the picnic table.

Larry, one of my two older brothers, is in seventh grade now. Jeff is in sixth, I’m in fifth. He comes up the steps, says “Move, shrimp.” I lean out of the way.

The tautog (Tautoga Onitis), also known as the blackfish, is a species of wrasse, native to the western Atlantic Ocean from Nova Scotia to South Carolina. – Original Lithograph Print by Sherman F. Denton

My grandfather says “Jackie, you wanna see somethin’?” He nods toward the two baskets. His eyes follow me as I walk over. One had gray hand lines coiled around flat pieces of wood. Lead sinkers hung from clips. Long black hooks dangled off the ends. The other basket contained a few flounder, a small sand shark – fish from a world I’d never visited. I looked back up at my grandfather.

“Where did you go?” He took off his glasses, cleaned them with a handkerchief. His pale, unfocused eyes made him seem older, more vulnerable. I stared back at the fish.

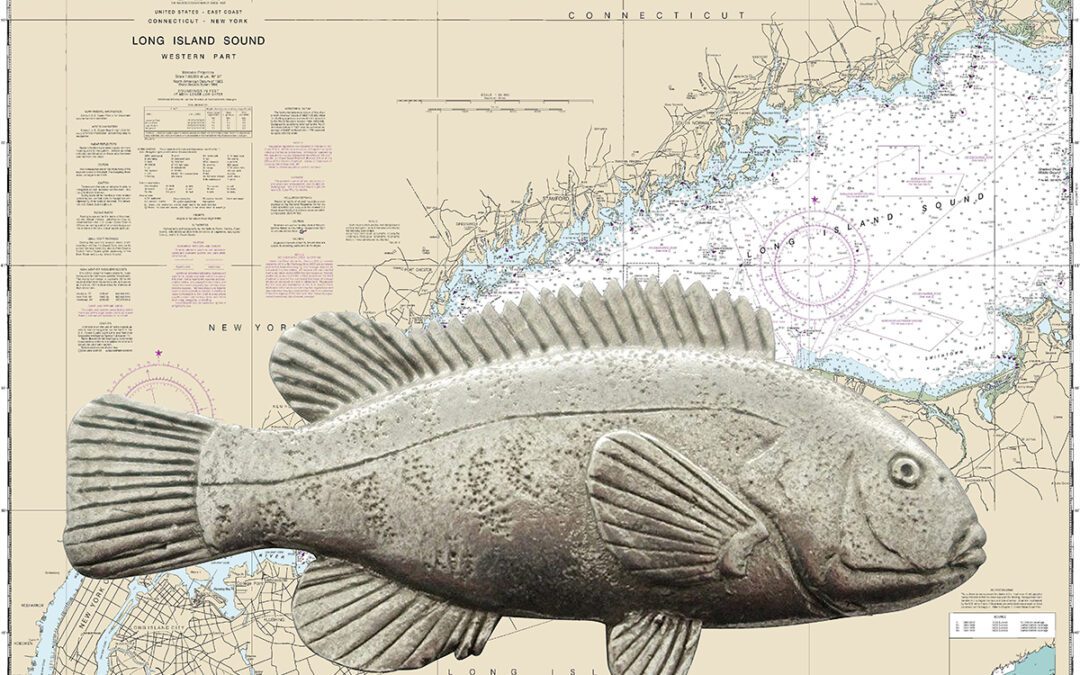

“On Long Island Sound,” he told me. “On a boat called the Dolphin.”

Larry came out of the house with old newspapers, spread them on the picnic table. Jarvis put a flounder on top of them, started sharpening a knife. My mother came out, suggested I come back to the porch, then sat down next to me.

“Did Gramp tell you where they went?”

“Yeah. On the Dolphin. When can I go?”

She pulled me to her with a gentle hug. Then the awful words: “Maybe when you’re a little older, Jackie.” And it got worse.

Jarvis replaced the hand lines with stout saltwater rods and proper reels. He and Larry started bringing home dozens of flounder. I would hear them on Saturday mornings. The automatic garage door went up. Car doors creaked open, thudded closed, the engine started. I’d watch out my bedroom window as brake lights blinked, back-up lights came on. They rolled out of view as the garage door went back down.

Two months later, my Uncle Jack and Joe May, an old friend of my grandfather, were over for dinner on a Friday night. They were all going out the next morning to fish on the Dolphin. Larry, of course, would be included.

It was just getting light out on Saturday morning when I felt someone gently shaking me. When I opened my eyes, it was my grandfather.

“Jackie,” he asked softly. “Do you want to go fishing?”

“On the Dolphin?”

He just grinned and nodded.

I dressed like I was in a race. When I got down to the kitchen, Larry and Jeff were already there. Uncle Jack and Joe May would accompany my brothers.

Captain Ed Brower greeted us as we boarded. He was about 50, 5-foot 9, and thin with high cheek bones and a small, square-jawed face. Curly brown hair mixed with gray was topped by a short brimmed captain’s hat, tilted slightly back. His face and hands were weathered and tanned. Ed looked down at his watch. Quarter to eight. We’d be leaving in 15 minutes.

Men joked with one another as they arrived. They fastened their fishing rods to the safety railings that ran down both sides of the boat, staking out their positions. Ed was squinting at his watch again when his wife Laura hurried down the dock with four large, flat, cardboard boxes. She was thin, tanned, dressed in drab work clothes, her brown and gray hair pulled back into a ponytail. She said, “Sorry I’m late. Had to wait for the worms to arrive.”

Ed set the boxes down on the large beverage cooler that stood in the middle of the back deck. Laura quickly surveyed the crowd on the boat, looked back at Ed, said, “See ya tonight, Dad,” and left.

Ed opened the top box, pushed aside a layer of shining seaweed. Some of the sandworms were nearly a foot and a half long. Ed picked one up. I winced when two black pinchers protruded from its distended mouth. Ed laughed. “You’re not afraid of the bait are ya?”

Jarvis removed the lid from a bushel basket next to the worms. It was full of small green crabs crawling on top of one another. When he picked one up by the legs, it flexed its claws in protest. He leaned over, told me he’d take care of our bait.

My brothers, Uncle Jack and Joe May found places near the bow. My grandfather rented a rod for me and tied it to the rail next to his, a couple places up from the stern. The starter whined, then the diesel engine rumbled to life under the front deck. The first mate hopped off, untied the dock ropes, hopped back on. Grinning, yellow-beaked gulls screeched and circled above us. The hum of the motor grew louder, the wake started to churn, as Ed accelerated past the harbor breakwater.

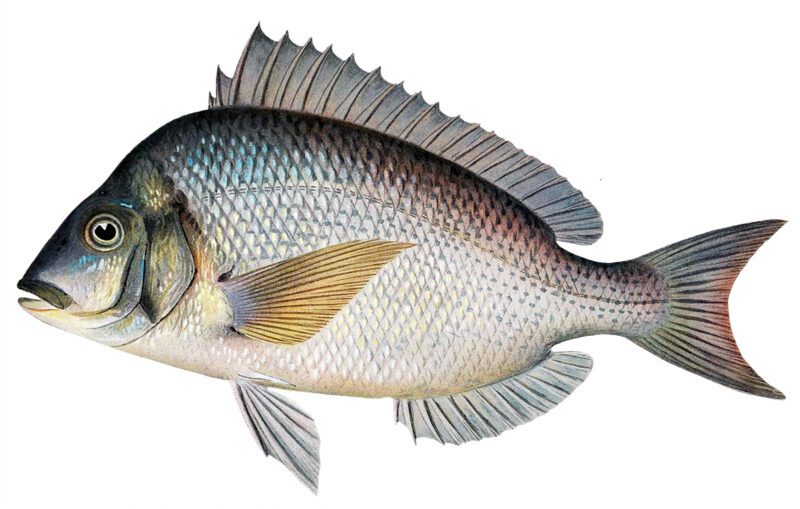

Scup, commonly known as porgies, were in abundance. They were called bouncers because when you reeled them in, the rod tip gyrated up and down. Porgies are thick, silvery fish more than a foot long, weighing up to two pounds. They were giants compared to the panfish I caught at a pond near home. My brothers found other things they’d rather do than fish, but I couldn’t get enough. My grandfather rarely went without me.

I learned that the tough head of a sandworm stayed on the hook. You centered the point between the pincers, pushed the worm up to cover the hook, pinched it off. You grabbed crabs from behind, twisted off the claws and legs with your other hand. At first I used gloves, then I just barehanded them like my grandfather.

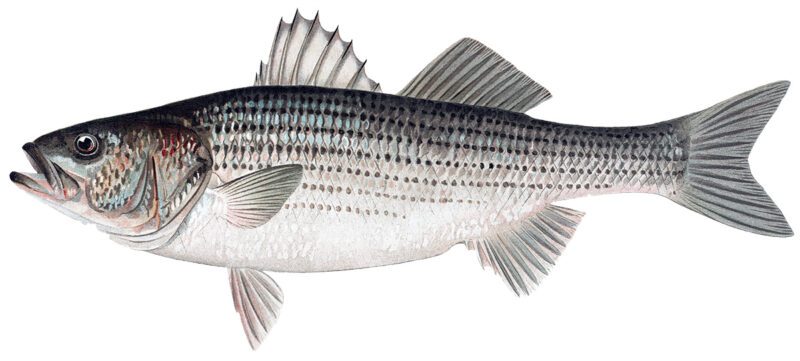

You cut a crab in half, used one piece. The hook went through a leg hole, was curled back just enough to poke the point through the bottom shell. The blackfish that ate the crabs were beasts that could weigh more than ten pounds. Sometimes I needed help reeling them in.

I got to know the names of the places we fished: Russian Beach, mouth of the Housatonic, Buoy Nine, Middleground Light, the Oyster Beds. There was nothing I enjoyed more than being with my grandfather out on Long Island Sound.

When the Saturday fishing was especially good, on our way in my grandfather would cock his head and gaze up at the sky. “You know what Jackie?” he’d say, as he looked back down at me. “I think maybe we ought to come back – to–mor–row.” Tomorrow was drawn out in three distinct syllables, emphasizing the importance of the decision. Then he’d grin at me and wink.

My mother hated our early Sunday morning ritual. For breakfast, my grandfather fried fish we’d caught the day before. The margarine he cooked them in always burned a little before he turned the flame down on the gas stove. Pungent, greasy smoke hung in the air when we sat down to eat.

I remember hearing my mother’s footsteps coming down the stairs. She stopped on the landing above the kitchen, half-asleep, waving her hand in front of her face. She looked at the clock on the wall over at the empty frying pan on the stove, then at her father.

The scup (Stenotomus chrysops)is also commonly known as porgy. Scup can grow as large as 18 inches and weigh as much as 3-4 pounds.

“Geez Dad!” she complained. “Turn on the exhaust fan. Or open a window.” He looked up at her, but said nothing. She looked down at me, her face wrinkled in disgust, as I chewed another forkful of blackfish,

“You really like that stuff?” she asked me. “For breakfast?”

“Uh-huh.”

When we heard her going up the stairs and back to bed, my grandfather looked at me. He raised his eyebrows, gave me an “Oh well” hunch of his shoulders. I gave him one back. I was 12 years old now, and proud to be a weekend regular on the Dolphin. We were a disparate group.

Peter Leon, a tall, affable Greek, was the president of the Star Taxi Company in Bridgeport. Wealthy enough to fish anywhere, his patronage of the Dolphin was testament to Ed Brower’s reputation. Peter was always over-dressed in docksiders, pressed khakis and a button-down collar shirt. With his large straw hat, he looked like he belonged on top of a horse, overseeing a coffee plantation instead of on a head boat.

Ed Brower’s first mate, Ed, was referred to as “Big Ed.” He was a portly, balding man in his mid-40s with too much height and muscle to be considered overweight. He wore a hat that matched the captain’s, had a round, pink face, and thick-fingered, heavily callused hands.

The middle-aged guy they called “Whitey” was as pale as can be with freckled arms and a perpetually sunburned nose under his Yankee’s cap.

Then there was “One Hook,” a diminutive, quiet soul I guessed to be in his mid-60s. A black watch cap topped his curly white hair and jaundiced eyes. His nickname referred to the way he always rigged his line. He spoke very little English, but he’d smile and shake his head enthusiastically when people said hello. His frayed shirts had seen better days. Pants too large for him were bunched under his tightly drawn belt.

One Hook always arrived early and fished when we were still at the dock, oblivious to the rainbow swirls of engine oil and detritus that floated in the harbor. My grandfather surmised that the fee for the boat trip wasn’t small change to One Hook. Sometimes my grandfather gave him a few of our fish.

One morning before we left the dock, I saw One Hook lean over the rail and vomit into the water while he was fishing. He just stared straight ahead, pulled a pint bottle of whiskey from a back pocket. His hand shook as he took a long pull. I was too young to understand what I was witnessing.

One guy stands out from the rest. Anunzio Caramello was born in Italy, came to the States with his parents and his older brother when he was a baby. “Nuzzie” was in his mid-50s, about 5-foot 9, olive skinned, with a belly two sizes larger than his clothing. He had thick bifocals and wore two flannel shirts, the top one usually graced with an assortment of stains. Curly, reddish-brown hair mixed with gray was topped with a threadbare, equally stained engineer’s cap. I always enjoyed the aroma of the Parodi cigars he smoked.

Most of the time Nuzzie was either smiling or laughing. On the rare occasions he was being serious, or if he was putting you on, he’d knit his brow and tilt his head to indicate serious contemplation. His pleasant mood was frequently bolstered by mixing soda from the boat’s cooler with red wine he poured from a gallon bottle. He’d be glassy eyed by the end of the day, but I never saw him wobble.

There was always a voluntary, dollar-a-man pool for the biggest fish. On one trip, a guy who’d never been seen on the Dolphin before insisted on entering. His blackfish appeared smaller than the other finalist’s fish, but it weighed more. When we got back to the harbor and our winner was getting off the boat, the captain yelled “Hey!” When the guy turned around, Ed shouted “Don’t ever show your face around here again, you son of a bitch!” The man did not reply. He just hurried up the dock. Ed told us that when he picked the fish up, he could feel sinkers stuffed into it. He didn’t want to create a scene out on the water, so he didn’t say anything.

A couple weeks later, Nuzzie won the pool with a blackfish just slightly heavier than one my grandfather caught. Nuzzie gave me a heads up and winked. He checked to be sure Jarvis was distracted and stuffed two large sinkers into the fish’s mouth. He waited until Jarvis was looking, then he cut off the fish’s head and the sinkers tumbled out onto the cutting board. Nuzzie’s eyes grew wide as he looked up at Jarvis. My grandfather tried to look shocked, his eyebrows raised high, his mouth hanging open. Nuzzie couldn’t contain himself. He broke into a big smile, then both of them started laughing.

One trip on the Dolphin was different from all the others. It was late August, two weeks before I started high school. We arrived late and, as we hurried down from the parking lot, we could see the boat just starting to leave. Laura Brower was walking back up the dock, saw us, yelled to Ed. He backed up so we could get on.

It was a warm morning under a clear sky. A light chop and a stiff breeze greeted us as we left Bridgeport Harbor. Once we reached the fishing grounds the captain let the boat drift, a common practice that locates fish.

The wind picked up. Rolling waves that slapped the sides of the boat made it too difficult to fish. We’d never been out when it was this rough. Ed had to run under power now to control the boat.

My grandfather and I were seated in the stern. We watched Big Ed come up from the engine room and stop at the bridge. Big Ed took the wheel, the captain went below.

When Ed Brower came back up, he walked quickly down to where we were sitting.

“Jarvis,” he asked, “Would you take a look at something for me?” There was urgency in his voice. My grandfather and Ed Brower went below deck. The Dolphin’s bilge pump had stopped working. Water was coming in.

Ed Brower came back up to the bridge, took the wheel. Big Ed walked to the front, dropped the anchor. The bow swung into the wind, the engine now idled in neutral.

Big Ed joined Jarvis below deck. Ed Brower was on the radio. I heard “Mayday! Mayday! This is the fishing boat Dolphin.”

My grandfather came up from the engine room, walked to the stern holding a life jacket. After he helped me put it on, he looked me straight in the eyes and said, “Just sit right here, Jackie, until I come back, okay?” I assured him I wouldn’t move and he went below deck again. I wondered how cold the water was.

I don’t know what magic my grandfather performed, but he got that bilge pump going again.

Big Ed came back up, stopped on the top step. Jarvis came up behind him. They leaned in toward one another, exchanged a few quiet words, then shook hands. Big Ed gave a thumbs up to the captain, walked to the bow, pulled up the anchor.

The engine’s idle rose to a loud drone as we started to move forward again. My grandfather sat down next to me, rolled his eyes. I started to ask a question. He put his finger to his lips and said, “I’ll tell you later.” Only three men on that boat knew how close we had come to sinking.

As we made a slow turn, the captain made an announcement: “We’re going in folks. Sorry, but it’s just too rough to fish today.” When we chugged past the breakwater into the calm haven of Bridgeport Harbor, it was like waking from a bad dream.

Atlantic striped bass (Morone saxatilis), also known as the rockfish, are the state saltwater fish of New York. – Painting by Sherman Foote Denton

Before he pulled out of the harbor parking lot, my grandfather stopped and looked over at me and said,“Know what Jackie? I think we’d have been better off if we had missed the boat today.” Driving home, he gave me the details.

When Ed Brower realized the gravity of our situation, he told Jarvis he didn’t have enough life preservers on board. That’s when my grandfather came back and put one on me. Questions will always remain.

Without enough life jackets to go around, how long would the captain have waited before he handed them out? Would men have fought for them? Would my grandfather have gotten one?

Jarvis said we would have been better off if we hadn’t gone, but what about everyone else on the Dolphin that day? Was it luck? Fate? The dictionary defines Providence as God, or a force that arranges things that happen to us. Fifty-five years later, I still think someone, something, made sure that Jarvis DePledge was on that boat.

The captain’s nearly tragic carelessness provided stark lessons for a 13-year–old. Most heroes do have feet of clay. And what gives you extreme pleasure, can also kill you.

The following spring, Ed Brower had a brand-new boat. We took a couple trips on it, but that was all. Nuzzie was noticeably absent, as was much of the old crowd.

I was in high school then. I had new friends, new priorities. Trout fishing had become my number one passion, but whenever Gramp and I were together, the conversation always led back to the Dolphin.

In his 70s now, Jarvis’s legs started to bother him.

“Jackie,” he told me. He wrinkled his nose like he smelled something that had spoiled. “My pins just aren’t what they used to be. I’d have a hard time standing on the boat now.” He encouraged me to go, but it would never have been the same without him. I’m sure he knew that.

When the house here in Maine is quiet, I hear the refrigerator motor cycle on and off. When it starts, it drones a note the exact pitch I used to hear from distant ship’s horns on foggy mornings out on Long Island Sound. I hear gulls cry, and the steady drone of the engine. The wake is churning behind the Dolphin again. Nuzzie and my grandfather are laughing.

Read on as some of the sport’s most talented writers recount their personal memories of catching bass, trout, bluefish marlin, tuna, and more. Explore the Pacific with Zane Grey, as he fights a 1,000-pound blue marlin, or listen as A.J. McClane explains just what it really means to be an angler. Take a step back in time when you read Ernie Schwiebert’s tale of fishing a remote lake in Michigan, when he was still only a young boy. Each of these stories, selected because of its intrinsic literary worth, reinforces the unique personal connection that fishing creates between people and nature. Buy Now The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish.