All the gauges are useful for some purpose or other, and I love ’em all. But a twelve? A twelve will do damn near anything!

A while ago, I reviewed Remington’s 12-gauge, V3 Tac 13. Despite its short barrel and abbreviated stock, I found it to be a truly versatile firearm. To tell you the truth, though, the same can be said of nearly any 12-gauge shotgun.

Many years ago, when I was growing up in deeply rural mid-Georgia, nearly everybody owned one. If you lived on a farm in that time and place, there was a 12 gauge behind nearly every door. It was partly for security—every family accepted the responsibility for taking care of themselves. The reality was that in the event of trouble, the arrival of aid from the sheriff was sometimes measured in hours, or even days. Back then, very few country folks even had a telephone. The same was true for folks who lived in small towns like ours.

We were, above all else, an independent and self-sufficient lot. Crime was rare, because every “criminally inclined person” knew the consequences of messing around with other folks’ person or property. A 12 gauge is about the most convincing tool I know for that job. Someone, I can’t remember who, famously said that “an armed society is a polite society.” Maybe that’s how Southerners came by their reputation for politeness!

Why a 12 bore, specifically? Because in those days, that’s what we had. The current small-bore craze hadn’t even been imagined. The standard gauge was the 12. As a result, 12-gauge shells were cheap and available at almost every hardware store. And they would do anything that might be required of a shotgun.

There were a few 16s around in the hands of the “enlightened,” and those who were affluent enough to own more than one gun. My uncle, Robert Weeks, and his son, “Cousin Bob,” fell into the former group. Both of them had beautiful Winchester Model 12s in 16 bore. I never knew why until I tried one many years later and could afford more than one gun. In time, I became a fan of the 16, but even then, I often reverted to the 12 when one was appropriate for the task at hand. After all, the 16 is a glorious thing, but not quite as versatile as a 12.

Hunting was strictly for birds and other small game. Quail, doves, rabbits and squirrels were plentiful, to say nothing of ’coons and ’possums. We gladly ate them all. Since we lived squarely between the Atlantic and Mississippi flyways, there were only a few waterfowl, and an occasional woodcock in wintertime, but we took them as targets of opportunity. The 12 worked for them, too.

Lefever Trigger Plate Type, 12 gauge. PHOTOGRAPH BY WILLIAM HEADRICK

There were no deer or turkeys to speak of in that part of Georgia at the time. They had been hunted to the brink of extinction long before. As a result, we were considerably perplexed as to what to do when deer began their resurgence in the 1960s. Nobody I knew had a “high-power” rifle, because we had had no need of them and spending hard-won dollars for a separate gun for hunting “unicorns” was unthinkable. After all, you might hunt hard for years without actually seeing a legal buck. Though I desperately wanted one, the cost/benefit analysis of buying a thutty-thutty was not favorable.

Until the late ’60s, it was largely an academic exercise. Then one chilly fall evening, Cousin Bob called with the news that he had located a “honey hole” near Eatonton that held a fair population of the rare creatures. Furthermore, he’d share his find with me, if I’d like!

What followed was a case of mixed emotions as strong as seeing your mother-in-law run off with your new Cadillac. On one hand, I really wanted to bag a deer. On the other, I had nothing to shoot one with. Up until then, my trusty 12-gauge Lefever double had sufficed for everything from snipe to geese.

By then, I already knew the limitations of buckshot. With the shells available, it was only effective to about 30 yards. I had been told that with luck, you could stretch that just a bit by using a rifled slug, but only if the gun sported real rifle sights. And I surely wasn’t about to defile the beautiful old brown-barreled Lefever with those.

About a week after Cousin Bob’s call, I stumbled across a rusty old 12-gauge Stevens 311. It was an unlovely beast, to say the least. It was pitted all along the barrels and, to make matters worse, the muzzles had been damaged and the barrels had been hacksawed off to about 20 inches. Consequently, there was no choke in either barrel. The owner had refinished the stock with 3-in-1 oil, which accounted for its sickly yellow sheen. To his credit, he didn’t ask extra for the “custom work.” After a bit of haggling, I offered him the princely sum of $15 and drove home with the disassembled 311 stuffed into a paper bag so nobody would see the wretched old thing.

What followed can only be described as a fortuitous confluence of youthful exuberance and blind ignorance. To my surprise, the barrels still placed buckshot patterns in roughly the same place at short range. Seeing that, I was encouraged enough to pilfer a set of sights from a junk .22 that a buddy had, and screw them to the top of the rib, just like the fancy double rifles that I had seen in magazines. By then, I had a crowd of at least a half-dozen boys and young men who were following the experiment.

Of course, the next step was to have a go at “long range” with rifled slugs, but when I tried rifled slugs, the barrels wouldn’t print within 15 inches of each other at 100 yards. Bummer!

The good news was that a little trial and error revealed that the right barrel, used alone, would keep three shots in a hand-sized group at that range. I might not have a double rifle, but I had a reasonable facsimile of a Cape gun. With double-oughts in the left barrel and a slug in the right, I had ’em dead to rights, near or far, short range or long.

And it worked out just that way, too. When opening morning came, my elder cousin led me into the woods in the pitch-black pre-dawn, scraped the leaves from the base of a huge white oak and sat me down with my back against the yard-wide trunk. When the eastern sky pinked, I could see that the oak towered along the lip of a deep ravine. A small trail ran across the slope about 30 yards to my front. It was bone-chilling cold, but Bob had strictly instructed me to stay put, stay still and stay quiet. So I did.

When the time came, a little doe streaked full-bore down the trail, followed in short order by a smallish four-point buck. The load of double-oughts from the left barrel caught him in full stride and he stumbled but didn’t fall. When he slowed and paused for a moment about 70 yards out, the slug from the right barrel took him squarely behind the shoulder and he slid all the way to the bottom of the “holler” before he pitched up against a small cedar and stopped.

At home a scant two weeks later, I removed the sights from the old clunker and fetched home a 15-bird limit of bobwhites and a couple of woodcock from the sedge fields of the family farm.

The whole point of this little story is that all the gauges are useful for some purpose or other, and I love ’em all. But a twelve? A twelve will do damn near anything!

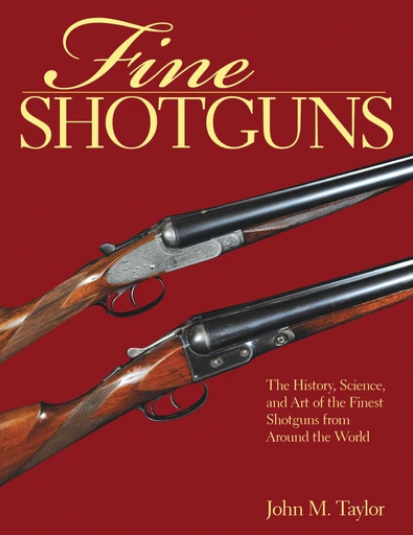

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes, and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case.

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes, and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case.

John M. Taylor began hunting with his father at age five. For the past thirty-five-plus years, he has written for major outdoor publications, including Petersen’s Hunting,Gun Dog,The American Rifleman,Outdoor Life, and more. He is currently the shotgunning editor of Sports Afield, Delta Waterfowl, and Pheasants Forever magazines. He lives in Lorton, Virginia. Buy Now