The rifle was all they talked about. A slick new Winchester Model 94 resting in the glass showcase at Harden’s Hardware. Jack coveted it. All the boys did.

An inveterate hunter all of his long life, Mr. Harden smiled at the boys’ enthusiasm. Recalling his excitement at their age, he allowed them to gather near the gun so long as they didn’t interfere with his regular customers. The boys liked him and spoke openly around him.

“I wonder who’s gonna win it.” Perry pressed his forehead against the glass for a closer look at this year’s prize for bagging the biggest buck in the county.

“Me.” Jack pantomimed the kill, mock-shooting a glassy-eyed, dusty deer mount nailed to the wall and rocked back from imagined recoil. “Boom! Mr. Buck down on the ground.”

Perry guffawed. “You? Yeah, right. You couldn’t hit the ground with your hat even if your dad does let you hunt this year.”

“Laugh all you want, Perry, but I’ve been keeping my nose clean. Dad and I already got a good spot picked out for me . . .

lots of big tracks and rubs plus we’ve seen Bullwinkle twice this fall down by the creek. The neighbor saw him too. Said he’s got more points than you can count.” He raised his arms and framed a finger rack over his head with both hands.

“Don’t matter if he’s got more points than Wilt Chamberlain, with that mule-kicking pumpkin-thrower of yours, you’d have to tie him to a tree to get close enough to hit him.”

“We’ll see,” Jack countered, catching Mr. Harden’s amusement at Perry’s comment. “I figure I got as good a chance as anybody else, and I plan to win that gun if it’s the last thing I do.”

“You said that last year too,” Perry quipped, “and that was the last thing you didn’t do because you were grounded as usual before the season even started!”

“This year is going to be different. I plan to stay out of trouble.”

Then Jack mimicked shouldering the Model 94. Racking a shell into the chamber and squinting down the iron sights, he squeezed off another mental round at the mount. He visualized the deer dropping stone dead at 100 yards, a shot he practiced once too often during English class when he was supposed to be diagramming sentences.

“Jack, suppose you put down the gun and pick up your pencil, unless you want me to call your father again,” his teacher had warned.

“Yessir.”

“So much for staying out of trouble,” Perry had whispered across the aisle.

Later Jack replayed the conversation in his mind with his friend. A twinge of remorse clouded his mood, and he wished he hadn’t mentioned the deer. Perry had a mouth like a magpie, and Jack’s father had warned him to keep quiet about the big deer. Word traveled quickly in a small town, Jack knew, and once the other boys heard what he’d said, they’d tell their relatives. With deer season this close, more hunters than ever might decide to pile onto the public land that crowded his grandpa’s property for a crack at Bullwinkle and a chance to win the 94. Then again, he wouldn’t be in the woods at all if his father found out he was loafing in school. It wasn’t the first time Jack had been chastised for daydreaming during classes.

A young, confident Jack Troutwine shivers in a stick blind awaiting dawn’s early light, shotgun resting on his lap. His steely eyes scan the forest. Overhead a canopy of stars glitters like gems strewn over a jeweler’s black cloth. Somewhere in the graying light a cock pheasant crows and owls trade questions. When Jack calls back, they answer. Jack’s gaze searches the far side of a trout stream where moonlight splinters on rapids gossiping over stones, ribboning his grandpa’s property like a present wrapped for him. Rich with expectation, he knows today is his day.

Mirage then miracle, the monster buck eases from the treeline, silent as whisper and slow as sunrise, a shadow of subtle movement. When the deer dips its head to drink, Jack grins at the immensity of its antlers.

“Bullwinkle,” he mouths.

Crouched in ambush, calm as a cucumber, Jack slides a slug into the Stevens single-shot, a relic forced on him by his father, and muffles the closing of the breech with his mitten. Sensing danger, the deer noses the wind, tail flicking nervously for the flight to come. Jack freezes and cocks the hammer with confidence.

Click.

Whirling, the big buck bounds up the streambank and races for sanctuary. Taking aim, Jack anticipates the route and effortlessly swings into the shot, threading a slug through the dense trees into the deer’s heart. After the crash he opens the breech, catches the hull in midair, and waits in silence, knowing the Winchester is won.

“Jack?”

“Um . . . yes?”

“Why don’t you enlighten the class with what you know about Walter Mitty?”

“Who?”

“I see. How about The Lady or the Tiger? Did you at least finish that one?”

After the teacher called, Jack knew what would be waiting behind the door for him when he got home.

Truth be told, even Walter Mitty would miss with the Stevens. Jack hated it, embarrassed by the battered, silver-barreled 12-gauge single-shot flintlock that once belonged to his great-grandfather, who had killed his first buck with it. A faded picture of him holding the gun and grinning beside a heavy-antlered buck still hung over the fireplace.

Passed down through the generations from boy to boy, the gun was embedded in Troutwine tradition as firmly as that big oak still rooted to the soil out back. A beginning hunter’s rite of passage included, among other things, carrying the old gun for a minimum of two years or until killing a deer, whichever came first. Jack found such reverence for ritual corny, something cooked up by old men lost in the past. Why handicap someone with a one-shot beater just because some dead relative killed a deer with it? Even Perry was allowed to carry a pump-gun.

The only one ever to beat the two-year requirement was his grandfather, who reportedly took an eight-point his first year afield at the age of nine, a surprising and questionable feat given his size back then when compared to the heft and length of the Stevens. Unless he were Popeye after a can of spinach, there was no way such a small boy could’ve shot that deer with the Stevens. Suspicious, Jack figured the tale was bunk concocted to impress nimrods like him into thinking they had a ghost of a chance of taking a deer with the relic.

Worse was the extended apprenticeship where would-be hunters at an early age accompanied their fathers afield to learn the lore and earn the “privilege” to hunt. Safety, ethics, tactics, rituals . . . the worst being repeated, grueling drives through the alder swamp in an effort to push deer toward the older hunters . . . were paramount to each boy’s training. These initiations also included blind building, knife and hatchet training, compass proficiency, tracking skills, knowledge of weather conditions, and gun handling. By the time a Troutwine finished his tutelage and was allowed to carry a gun in the deer woods, he was expected to know right from wrong and he was usually 12, much to 15-year-old Jack’s chagrin.

It was no secret that Jack chafed at the restrictions and expectations imposed on him. His conduct often warranted punishment and delayed his acceptance to deer camp except to work the drives and clean up the campsite. There was the matter of frogs, turtles, sparrows, and chipmunks slain for no reason, BB-gun killings found by his father who suspended Jack’s “hunting” by taking a hammer to his Daisy and grounding him for a summer.

The silent disappointment radiating from his father that day shamed Jack, but his bloodlust was equally compelling. Later killings went hidden . . . raccoons, possum, squirrels, and rabbits out of season, even a hen pheasant. Jack’s sneaking and shooting of the .22 going unreported and unknown until a neighbor saw him take a bead on his cat. It was nearly the last straw and would have been if not for his mother’s intervention. She believed a third chance was warranted if Jack were ever to redeem his father’s trust and become the man he wanted him to be. She brokered a deal to make amends. Jack spent a month cleaning chicken coops and shoveling cow flop for the offended party.

“Sometimes shoveling a lot of crap is the road to contrition,” his mother had offered, hoping the penance would hold.

Somewhere between the first shovelful and the last, it did hold, at least outwardly. Jack’s recalcitrance faded, his epiphany taking on the sheen of pragmatism. There would be no hunting, he realized, unless he followed the rules. In time his father softened and forgave him, ready to welcome his prodigal son to the hunt given his seeming reformation.

To confirm his trust in the boy, Jack’s father left a box of Peter’s blue slugs by Jack’s plate one morning, signifying what was to come. Marksmanship, the final phase of an apprentice’s training before earning the Stevens, started in earnest for Jack the summer before his expected debut.

It was the ultimate test of a boy’s stealth, skill, and determination to take a deer. Accuracy beyond 30 yards with the gun was improbable but within 30, possible. Jack knew this from the paper pie plates he’d practiced on to get a feel for it. Flinching from the recoil that staggered his footing and decorated his shoulder with purple epaulets, Jack rarely fired more than three rounds. Under his father’s watchful eye, Jack’s shooting was beyond dismal at first, but he kept at it, leaning into the gun, gritting his teeth and hanging on like Ahab to Moby Dick until tighter groups emerged.

“I don’t want you shooting beyond the gun’s capabilities, you understand? Reckless shooting is a hunter’s worst sin because it results in the wounding and wasting of life.” Pausing, his father arched an eyebrow. “We’ve covered this ground before, haven’t we? So you remember, a good hunter . . .”

“. . . is a good man. I know, Dad,” Jack finished.

The final part of the challenge entailed a mock stalk where a deer silhouette was hidden somewhere on the property. Jack’s first task was to locate, decipher, and select the correct set of tracks. Once found, usually partially obscured in brush or cattails along the creek, the deer presented a heart-shaped target taped beneath a foreleg. Prior to shooting, Jack was expected to evaluate distance and creep within 30 yards of the silhouette before firing a slug into its “heart.” Two shots were allowed; Jack nailed it with one.

The family toasted and cheered his success at a celebratory dinner that evening. Jack thought it mostly hokum but played along, even feeling a flash of pride when his father handed him the Stevens in front of his relatives. The significance of the upcoming hunt was not lost on him.

Late afternoon before the November 15 opener, Jack tarried at the hardware for one last longing look at the Winchester before Mr. Harden closed up early for the day. Except for Jack, no customers remained. Everybody knew Mr. Harden was a hunter too even though he was nearing 80. Wearing a tattered apron and surrounded by all the clutter you find in a small-town hardware, he looked antiquated to Jack in the waning afternoon light, like a Dickens’ character down on his luck. Men like Mr. Harden were a dying breed, his father used to say.

“So, Jack, your father was in here yesterday and told me he’s putting his trust in you this year and letting you go hunting.”

“Dad was here? How come?”

“Promise you won’t tell him I told you?”

Jack nodded.

“He bought you a new compass, one of these Marble’s pin-ons. He’s going to give it to you in the morning.” Mr. Harden picked up a brass compass and handed it to him.

“Oh.” Jack took it, puzzled. “But I already have a compass.”

Mr. Harden locked the front door before opening the cash register to count the money. “Not with the meaning behind this one, you don’t. Think of it as a moral compass. Your dad’s teaching you a lesson. He wants you to remember what’s important tomorrow.”

“He’s always trying to teach me a lesson, Mr. Harden.”

Jack watched him lay the bills, mostly tens, fives and ones, in uneven piles, thinking of their “fireside chats,” as his father liked to call them, like he was the Franklin Delano Roosevelt whom Jack had studied in history class. All that stuff about stewardship. Staying on the right side of wrong, doing what’s right, taking less than allowed, respecting the game, honoring the past, caring about the future.

“Living a hunting life is a special privilege, Jack. Your dad’s just trying to teach you the religion of it, and like any religion, there’s a litany to learn, a way of doing things. It probably seems like rigmarole to you, but it’s not.”

Mr. Harden glanced up and smiled at Jack.

“Why don’t you take that rifle out of the case there and see how it fits you? Go on, rack it and aim at that deer on the wall there like you did before.”

Surprised by the offer, Jack was speechless. Taking the gun gingerly from the case with trembling hands, he worked the lever, held the cool, blued steel to his face, and sighted down the barrel. It was the most beautiful blend of metal and wood he’d ever touched. He steadied the bead on the mount but kept his finger clear of the trigger like Mr. Harden hoped. Then he lowered the gun toward the floor, eased down the trigger, and clicked it back to safety.

“Who taught you to handle a gun like that?”

“My dad. He said once a hammer drops on a live round, there’s no taking it back.”

“My dad taught me that too,” Mr. Harden mused.

It was hard for Jack to think Mr. Harden ever had a father. “Only he said it a little differently. He said you can’t bring back a life once it’s dead . . . unless you’re Jesus.” The old man chuckled and then continued counting.

Jack returned the gun to the showcase. “What’s it like to shoot a deer that big?” he asked, pointing at the ten-pointer whose blank stare had greeted customers for as long as he could remember.

“There’s a pleasure and a regret to it.” Money counted, Mr. Harden stood and slid rubber bands around the bills. “You’ll see.”

“Thank you for letting me handle the gun, Mr. Harden.” Jack turned toward the door.

“Good luck tomorrow, Jack. I hope you get the one you’re supposed to.”

“Same to you,” Jack said.

By 11 a.m. a bluebird sky floated swollen clouds and framed an Indian summer day of soft breezes rustling among leaves left unplucked by autumn. By the time the frost melted Jack had eaten most of his lunch. He’d counted six chickadees, two blue jays, three squirrels, numerous flocks of crows, geese, and ducks, and no deer. He’d lost count of gunshots near and far that echoed over the landscape from other hunters, who reduced his odds of taking a buck from slim to none, he figured. Discouraged, he threw the apple his father had packed with his lunch across the creek where it stuck in the mud along the bank. Five hours of sitting had dimmed his enthusiasm. It was nothing like he’d imagined.

By 2 p.m. his attention flagged to occasional glances down the shooting lanes he’d cut and trimmed with such high hopes that summer. Stiff from sitting, he stood often to relieve himself of the thermos of coffee he’d drunk most of the morning. His mind wandered to girls, school, and some of what Mr. Harden had said. The Model 94 never felt farther away. His eyes drooped in the afternoon sun that warmed his face. Unbuttoning his wool coat, he dozed and his head bobbed and jerked, startling him awake each time his chin nicked the compass pinned by his father to the collar of his coat.

Hours later Jack felt the temperature cool as the sun slid down the sky and ignited on the horizon like a bonfire before dwindling toward dusk. Shadows gathered as the gold of day gave way to the blue of night. Jack buttoned his coat against the chill, in some ways glad the long day neared its end, when suddenly a badly injured deer hobbled into view on three legs. Struck by a bullet, one limb dangled like a puppet leg detached from its string. When the yearling turned to stare across the stream, Jack froze and his heart galloped before he noticed the broken leg and the buck’s three-inch horns.

Nearly a nubbin buck, he thought, not wanting to waste his tag and his chance to win the rifle when the real trophy waited for him. Thoughts of Perry’s ridicule made the choice even worse.

Yet he was sickened by the animal’s plight and knew in his heart the right thing to do, what his father and Mr. Harden would do. The lure of the Winchester pulled at him, though.

Pausing, he again followed the little yearling’s gaze to the far bank where the buck of a lifetime stared back, still chewing the muddy, red apple.

Breath ragged as a long distance runner, Jack cocked the hammer, aimed true, and fired, killing one deer instantly while the other melted into the woods.

“Once a hammer falls on a live round, there’s no taking it back,” he whispered, shaking badly.

It was a shot that would make all the difference for the rest of his life.

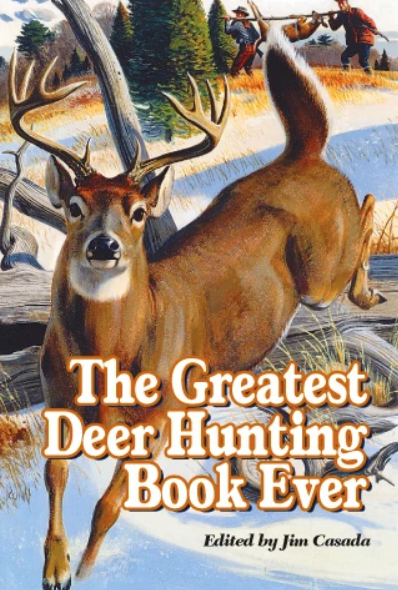

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor, Gordon MacQuarrie and many others. Buy Now