Perhaps it was only a trick of the water, a trompe l’oeil of the late summer light, or maybe just one of those hallucinatory visions provoked by hours on end of upstream nymphing. You know the feeling: cast, lift, reach, lift, cast again – over and over, always staring, until the world fades away, sun and bird song and roar of water, until all that’s left is the endless downstream dance of the strike indicator. But in that moment I saw the dead angler clear, down there in the depths beneath the floating red leaves.

I mean crystal clear, in detail. His waxen face with the hair floating vaguely in the current, pale eyes fixed upward on mine, the grizzled mustache trailing like eelgrass over a rueful smile, the blue collar points waving limply above the fishing vest. I could see it all in that mirror-light of underwater. A shattered black rod gripped in the stiff hand, forceps twisting silver from a retractor pin, the bulge of fly boxes in the buttoned pockets. A black-finished leader snips dangling from a D ring. Even the flies hooked into a fleece drying patch – dry flies – a Ginger Quill, an Adams, a Blue Dun and a fourth I didn’t recognize, the brightest of the lot. All clear, all seen clearly in an instant.

As I looked, horrified, he rose a bit from the bottom – lifted, it seemed, by the hackles of those flies on his chest, by some heavenly Mucilin or mystical Gink that urged him free of the rolling current’s downward grip. I grabbed for him, got hold of the slippery vest, arm-wrestled the current for a moment, felt the fabric slipping from my fingers, then a sharp stab of pain in my palm. I clenched. He broke away and down again. One hand rose, limply, as if in farewell, and he rolled back into the depths.

I staggered off into the shallows, stunned and disbelieving. Odd things happen to the mind on trout streams. Illusions and delusions are the bedrock of our sport. Maybe I’d imagined the whole thing. Maybe it wasn’t a man but merely a waterlogged tree stump, or the carcass of a drowned deer. But I’d seen it so clearly. Then I remembered the pain in my hand as I grappled with the body. Sure enough, there was a fly stuck in my palm, dead center. It was the fourth of the flies I’d seen on his vest, the odd one. Buried to the shank, I pulled at it tentatively, and it came right out – barbless, thank God. Absently, I stuck it in my own drying patch, then sat back on the bank, in the sun, to watch the pool for the body’s reemergence, but mainly to think.

What I decided, when the body failed to show again, may seem heartless and inhuman, but remember that I am a fly fisherman and the season was winding down. I decided to fish on. What else could I do? The truck was a good five miles downstream, and it was another ten from there by jeep trail to the nearest highway. By the time I got out, it would be midnight – no time to organize a search party with grappling hooks for a man already dead and beyond help.

I was fishing my way up Wendigo Brook, a little-known feeder of the Nulhegan River in the so-called Northeast Kingdom of Vermont. The region itself received little pressure from anglers – the locals are mainly “wormflangers” who fish near the bridges, and then only when the rivers are discolored from heavy rain – and this section was virtually trackless except for logging roads used seasonally and sporadically by the paper company that owns most of the land. I was packing in, light, with only a tarp for cover, and figured to be on the water for at least three days. There was a highway to the north where I could hitch a ride back to the trail where my truck was parked. So far, the weather had been splendid – high, crisp, sunny September days; frosty nights full of owl hoot and coyote song and, toward midnight, a dazzling display of the aurora. The trout were fat brookies and cagey browns, bright and savage in their spawning colors. Why give that up for a dead man?

A fellow I know told me how he’d been fishing for spring steelhead up in British Columbia once when he came upon his partner, dead of a heart attack on the gravel. “I reeled in the fish that had killed him, released it, then laid him out with a stone for a pillow and his rod alongside him like a knight’s lance,” he told me. “Then I went back to the river. What the hell, the run was still on.”

So I, too, fished on.

It was getting toward evening, time to look for a campsite and kill a couple of trout for supper. Ahead, the stream wound down through a grassy meadow, one of those dried-out beaver ponds that stud the country up there, with plenty of standing, sun-cured downed trees to provide firewood. I unslung my day pack and spread the tarp under a big white pine, built a ring from a fractured granite ledge, gathered enough wood for the night and laid a fire, then went down to the brook to catch supper.

Nothing rising yet, just the brown water coiling smooth and deep under the high banks. I pulled the dead man’s dry fly from my patch and examined it. A strange fly, this one. It was hair-bodied, kind of like a deerhair Adams a friend of mine ties with a big, fat body resembling an Irresistible or a Rat-Faced McDougall. But this clipped hair was of a color I’d never seen before – all colors, it seemed, the more I looked at it. In that late-afternoon light it almost glowed, refulgent and refractive at once. Blue and burgundy and mahogany, with glints of fiery green, as if copper wire were burning; a deep midnight luster in toward the hook shank, like the underfur of a fisher cat. It couldn’t have been dyed, not with all those ever-changing colors, and I tried to puzzle out what sort of animal that hair could have come from. Not badger or moose or wolverine or skunk, certainly not squirrel or bear – not even cinnamon bear. Marten or sable, perhaps, but I doubted it. Hackle, wings and tail were clearly from the same animal, and equally deceptive as to their true colors.

The hook, too, was of a type I’d never seen. It was a size 12, I’d judge, sort of Limerick-bent with a turn-up eye, japanned in black lacquer like a salmon hook, but of course far too small for that purpose. There was something archaic about it that called up images of Hewitt or Gordon tying late at night by lamplight, with a Catskill blizzard howling beyond the windowpanes, or perhaps Dame Juliana herself in some echoing abbey chamber with rush torches guttering on dank gray walls. Could it have been tied before stainless steel came on the market? Unlikely – the fly was not a bit tattered. Or maybe it just didn’t catch fish – that would account for its pristine state. But then why did the dead angler have it on his drying patch? What the hell, I’d give it a try.

I knelt in the bankside grass and worked the fly out toward the far bank with a few false casts. I still had a short leader on, the same I’d been using while nymphing, since this was just a trial run anyway and the tippet was heavy enough to turn over the big fly. The fly was traveling overhead in the higher light, and I could see it from the corner of my eye – glowing. A red-gold firefly, it seemed, above the oncoming dusk. I aimed to drop it on the deep run against the far bank, where a nice fat brookie ought to be lying, hungry and unselective as to his dinner menu. He would fill mine. But before the fly even reached the water, I saw a wake streak toward it. From my side of the water. Then another, from downstream. And another, from far upstream . . . . A huge, dark, golden-bellied shape leaped clear of the water and nailed the fly solid, a full foot above the surface. A big brown, by the look of him. He’d won the race. The other wakes turned sharply on themselves and chased after the brown, who hit the water like an anvil dropped into a lake.

Thank God for the heavy tippet. I was so stunned by the ferocity of the onslaught that I failed to drop the rod tip as the hooked fish jumped, then jumped again. The lesser trout jumped with him – half a dozen, it seemed, all in the same instant. All aimed at his mouth, where I could see the dead angler’s fly glowing in the brown’s hooked jaw. It was as if . . . It was as if they were trying to take the fly away from him.

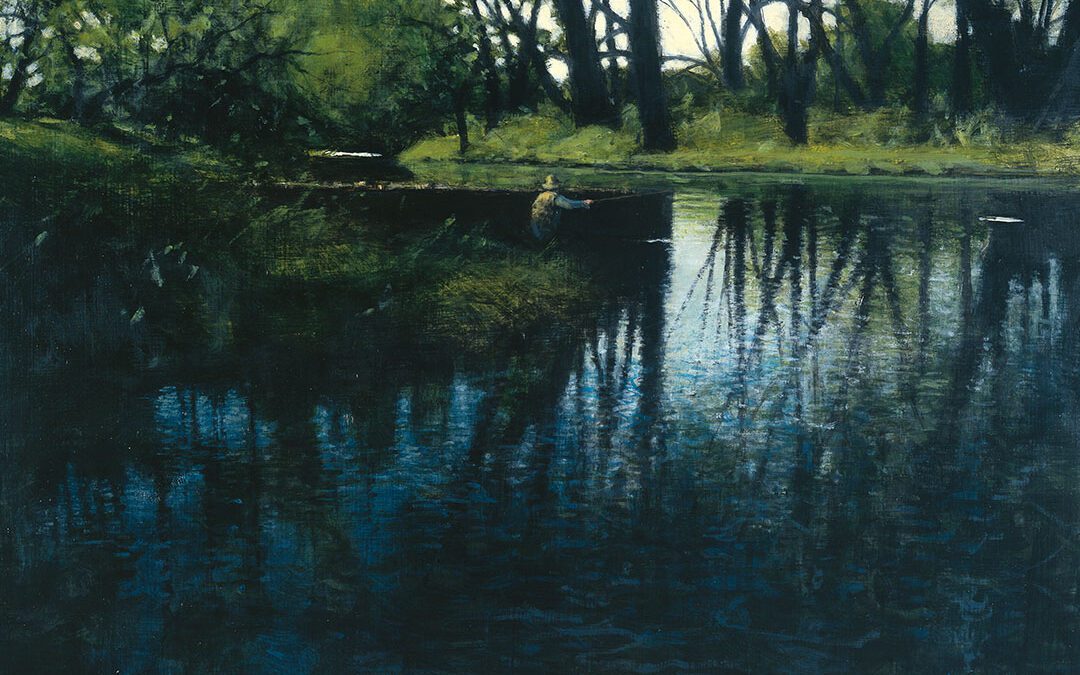

Down In Monkey Run by Thomas Aquinas Daly.

I snubbed the brown around, took him on the reel and horsed him in, panic gripping my heart. I hadn’t felt like this since I was a kid, fast to my first big fish and frantic that it might get away before I could land it and go running home to show my friends. But when I netted him and lifted him to the bank, he was too big to kill – a good 20 inches long, deep and thick and heavily kyped for the spawning run, far too big a fish for my supper, far too handsome to die. I slipped the hook and sent him back. The other trout were still there, in the bankside water, waiting as if for his return. As he swam off, they followed, darting at his mouth in puzzlement – where was that good bug?

What the hell was this? My heart slowed down and I moved upstream toward the head of the run. Once again I laid the fly out, once again the wakes appeared from all directions. Once again a big trout leaped clear of the water to glom the fly before it hit. Once again the other trout chased it.

Once again he was too big to kill. This was getting upsetting.

I took five more fish on five more casts as the light failed, each the same as the last. Now we’ve all had similar, or roughly similar, experiences at times, particularly at dusk, when almost any big bushy fly splatted on the water will take trout one after the other. I recall an evening on the South Platte, in the Cheesman Canyon, when I took eight nice Colorado browns on successive casts during a caddis hatch, without shifting a step from my position in midstream. But this night there was no hatch, not that I could see. And each fish took the fly before it hit the water.

I’d often seen brook trout chase one of their number after it was hooked, but brookies are notoriously naïve – some might say suicidal – in the face of danger. These trout, as best I could see, were browns – the Einsteins of entomological discrimination. And not little ones, still learning their Adams from their Baetis from their Coachman, but 15- and 16-inchers from the graduate school of Selective Sipping.

It was nearly dark by the time I wised up, cut off the dead angler’s fly and tied on a mothlike Grizzly Wulff. It took me well into full dark, float following fruitless float on the now-still, apparently troutless water before a lone, ten-inch brookie foolishly gobbled the fly and sacrificed himself for my supper. I knocked him on the head and whipped his guts out, shamefacedly, then stumbled back through wet grass to light my fire. The dinner – fried trout, baked beans, cold cling peaches from the can – leaves no memory of taste behind it, but I must have eaten it, because I remember walking back down to the river to wash the pan. The water was strong and black as ice-cold coffee, but I needed whisky. I lay against the pine trunk in my sleeping bag, sipping Scotch from the peach tin, my mind dancing like a skyful of mayfly spinners.

You’ve probably wondered, as I do, why certain flies that bear absolutely no resemblance to anything in nature not only catch fish but, at certain times and places, are the only flies a trout will look at. The Royal Coachman, with its white wings, rusty hackle, bristly barred tail and three-segment body, is perhaps the best example. I’ve heard it argued that the segmented body makes the trout think “flying ant,” while the white wings are there only to help the angler keep track of the fly in fast water. I’ve got another theory, and it came back to me that night as I lowered my Scotch supply and pondered the strange fly I’d found – a fly I’d started thinking of as Ephemerella incognita.

Trout have been around for millions of years on this planet, making a living largely off aquatic bugs, and during that time many insect species have come and gone, whereas the trout in its various forms has remained pretty much the same. Could it be that deep in the trout’s racial memory, taped on its genes as vividly as its spots and fin rays and mating instincts, are images of insects long since extinct? Images that, when presented in a certain light or temperature of water, by a certain curl of current over a specific type of streambed – sand or boulder or pea gravel – trigger a strike as inevitable as a salmon’s fruitless leap at a newly erected dam on its preordained spawning river? Maybe trout still feed on a long-dead past, just as men do on books long out of print but nonetheless still compelling. And perhaps this odd killer fly I’d come by, this E. incognita, by sheerest chance happened to imitate some splendid bug of prehistory, some trouty equivalent of braised sweetbreads or oysters on the half shell in an age of sawdust hamburgers . . .

By the time I sloped off to sleep, the Scotch bottle was down by a good three inches.

Fog on the water at daybreak – a pearly pea souper through which the spires of black spruce and the cracked, bone-white fingernails of snags poked, silent and dripping. Heading down to the stream for coffee water, I heard something splash away through the shallows. Moose, I thought. Their big, cloven tracks scarred the shore the full length of Wendigo Brook from where I’d entered it. After filling the pot, I went down to look for sign. I wish I’d never looked. There at the bottom of the run where I’d caught the big trout the previous evening were the carcasses of seven big browns. Clearly, they were the fish I’d hooked and released. But how could that be? I hadn’t played any of them to the point of exhaustion. I’d hardly touched them in removing the barbless hook, and none of them had swayed even slightly onto its side before swimming off strong and swift to cover. Now, though, they were just heads and tails connected with bare bones. Whatever ate them had some appetite. The skeletons looked like cobs of sweet corn gnawed from end to end, machine-gun style. Big paw prints surrounded the spot, not the long, plantigrade prints of a bear or a bootless man, but round ones a good hand span in diameter, with sharp, deep indentations, as if from claw tips at the end of the toes. A catamont? If so, it was the size of a Siberian tiger – my hand span is nine-and-a-half inches. Thank God the thing had finished eating before I came up on it . . .

I hurried back to the fire and stoked it with my remaining wood. When the water came to a boil, I spiked my coffee with another inch of whisky, then waited for the fog to burn off. I dug the .22 Colt Woodsman out of my pack, checked the magazine, and jacked a Long Rifle round up the spout. Not that it would do much good against a creature the size of that one, but it made me feel better with the holster slapping against my thigh as I packed and headed upstream as soon as I could see a hundred yards ahead. I resolved not to joint the rod until I was at least a mile away from that place, no matter how good the water looked.

But as the day brightened and the sun shone down strong and jolly, my worry burned off like the fog. I felt a fool with the pistol on my hip and put it back in the pack. There were trout rising everywhere – in the pocket water, the riffles, along the undercut banks, in the long, slick, stillwater runs and the deep, blue-green bottomless pools.

Would E. incognita work its wonders under conditions like this, where every trout in the river was already glutting itself on the tiny blue-wing olives I now saw emerging? The naturals were no bigger than 18s or 20s – a fraction of the size of the incognita. Even if I cast with the utmost delicacy, as fine and far off as I could manage, its impact on the water would probably put everything down.

I strung up, tied on and cast. At first nothing happened. The feeding trout continued to etch their endless, interwoven circles on the water, and I was about to breathe a sigh of relief – last night’s events had just been another of those rare lucky moments in a fly fisherman’s diary of strange happenings. But then another huge brown appeared out of nowhere and took the fly at the end of its float. In fact, the fly had been dragging abominably for half a minute while I stood there, falsely relieved that the mystery was explained.

I played the fish fast but carefully, took great pains to insure that I didn’t so much as touch it while pushing the hook with a fingertip out of the corner of its mouth. Again, it swam off in full strength, even splashing me with a faceful of water as it tailed away. Thus began, ironically, the most frightening, frustrating day of my angling life.

I tried the incognita in the most unlikely trout lies – in dead back eddies, in boiling currents too strong even for a tarpon, dapped it directly at my feet in seemingly fishless pools, even bounced it down a shallow, gravelly riffle no more than ankle deep. Wherever I dropped it, trout appeared, often as if from the streambed itself, out of ancient redds long buried under glacial till, springing in seconds from alevin to parr to smolt to full-grown, hooked-jawed, bloody-eyed lunkers hellbent on suicide. One such – a broad-shouldered five-pounder at least – actually zipped up through water only half its own depth from dorsal to ventral, scooting along the gravel on its pectoral fins like some giant wind-up toy. I’d seen king salmon do that on the Salmon River near Pulaski, New York, when the water was down and the fish themselves were pursued by a horde of two-legged snaggers, splashing and falling down in their lust for kill. But never the dignified brown trout. It was sickening – ignoble, repellent, downright hoggish.

And behind me, as I fished and tried not to look back, I saw fish after fish – all carefully released as tenderly as possible – go belly up in my wake. Every one that the incognita bit died. Yet I couldn’t stop fishing. Even as my mind shrank from what I was doing, as I cursed myself aloud, I kept casting, hooking, releasing but inevitably killing trout – trout of such a size and beauty that if I’d seen some wormflanger catching and killing just one, a day ago, I’d have seriously considered shooting the bastard and leaving him for the ravens.

Poison, I began thinking. Poison on the hook. What I took for black lacquer is actually some kind of deadly venom – like that black tar the Wandorobo hunters use in Africa, boiled down from the sap of the Acocanthera, and smeared on their hand-forged arrows and spearheads to kill even rhinos and elephants with the stuff. But I, too, was dying – going mad first, unable to stop what I hated doing, yet compelled by the poison to continue. Maybe in an hour, maybe not until tonight, I would gasp hopelessly for breath like those splendid fish dying behind me. Maybe I would roll belly up in my sleeping bag, eyes going white with death, and . . .

And what? Provide a midnight snack for that big, round-pawed carrion eater I’d surprised this morning by the riverbank?

That snapped me out of it. I looked at the palm of my hand where the hook had bitten me yesterday afternoon – less than 24 hours ago – but the wound was healed. As perfectly as if it had never been there. Nor was the flesh tender when I probed it. Oh, I felt a little woozy, but that might just be a touch of hangover from last night’s Scotch, plus the belt I’d had instead of breakfast. And I hadn’t eaten a bite of lunch. It was already late afternoon. No wonder I was giddy – too much fresh air, too much sun, too much adrenaline, too much imagination. When I looked back downstream, I couldn’t for the life of me see a single dead fish, yet just moments ago it had seemed there were dozens. Maybe I’d imagined the whole thing.

But the incognita was still clinched fast to my tippet. And with a pang of horror I saw that, for all the big fish it had taken today, all the spiky vomerine teeth that had raked it, not a wing was tattered, not a hackle point bent, not a tail whisk frazzled or a strand of dubbing trailing loose. With a shudder, I cut the fly loose and threw it into the current.

Before it could hit the water, a huge brown surged head and shoulders up and onto it – snap, like a giant mousetrap and he was gone.

At that same moment, a wind kicked up and, under its sudden roar, I heard a low, throaty growl from downstream. I turned and ran.

I slept that night on a rocky islet in midstream, wading out to it through currents that lapped over the top of my chest waders. There was ample driftwood jammed at the head of the island to build a huge, roaring bonfire. I kept the upholstered Woodsman beside me while I ate a frugal supper of beans, Spam and Bing cherries – no trout for me tonight. I’d killed enough in the hours just past to last a lifetime. I also reduced the Scotch level another few inches, trying to quiet my raging imagination.

To keep my mind off the day’s event, I dug out a book I’d brought along, as I always do on such trips, to read myself to sleep. Usually it takes half a page or less, after a hard, fine day on the water, but tonight I feared it would take longer. Keys to the Kingdom, it was titled, by Zadok Mosher. Being a Compendium of Myths & Legends Peculiar to Northeast Vermont. I’d picked it up in a fine little bookstore in Lyndonville that specialized in used books. No date of publication was given, nor was the name of the publisher, but clearly it was an ancient tome – glossy paper, antique typeface, faded leather binding, excellent drypoint illustrations, the sort of book no one makes anymore. I settled down into my sleeping bag, took a stiff wallop of Scotch and brook water, and opened the volume at random.

“The Monster of Wendigo Brook.” Uh-oh. But I read on.

The Wendigo is thought to be a myth of the Cree Indians of the western boreal forests [Mosher wrote]. A murderous creature, half cat, half man, that stalks its human prey through the treetops. When it catches an unwary Indian, alone and deep in the forest, it swoops down and grabs him, lifting its hapless victim high into the air. Then ensues a pell-mell dash through the night sky, conducted at such speeds that when the Wendigo – dragged groundward by the weight and frantic struggles of its still-living captive – allows the victim’s feet to touch the earth, the sheer friction sets his moccasins afire. The Wendigo, like a house cat, likes to show off its prey, frequently carrying it at chain-lightning speed around the camp from which the poor captive strayed. His kinsmen, huddled in their teepees, can hear him screaming all through the night: “Oh, my burning feet! Oh, my feet of fire!”

In the morning, nothing is found of the victim but his scorched clothing and picked bones, usually under a tall tree at the top of which the Wendigo, like an owl, has made his meal.

Such, then, is the Wendigo of the Cree. But the Abnakis of northern New England have their own legend – that of the Water Wendigo. Like its western congener, this creature too is a man-eater, though it much prefers fish. It haunts the virgin trout streams of that luckless country, hoping to find a dupe to catch fish for it. To that end, it ties a lure on whatever old hook it can find, using swatches of its own fur to disguise the fatal implement. This fur, the Abnakis say, is irresistible to trout and salmon, some of which have been known to crawl on their fins from lake to lake in pursuit of a lure of such devising. No sooner do they taste of it, than they die. Whereupon the Wendigo dines on their corpses. But since the Wendigo cannot cast a fishing pole by itself, it needs a human intermediary to do its fatal business in its stead. This it handily finds, the Abnakis say, since what man would pass up the chance to catch a fish with every cast of his lure? Should the fisherman object to sharing his catch with the Water Wendigo, the Wendigo kills him along with the fish, then passes the lure on to another victim. No man has lived to tell how. Nonsense, of course. But when you hear a withered old Abnaki tell the tale, in a skin lodge on a still winter evening with the Aurora guttering overhead . . .

That was enough for me. I poured another Scotch and resolved, then and there, to fish no more on Wendigo Brook – tomorrow or ever. Total nonsense, of course, as Mosher said, but I would not press my luck. I was lucky to get rid of the fatal fly when I did. I unjointed my fly rod and slipped it into its case, finished my drink, stoked up the fire and went to sleep.

The sun was already up when I woke, so sound and dreamless had been my rest. It was a beautiful day, clear and warm with just an apple-bright bite of frost in the shadows, the brook tinkling and purling along its merry way over the timeworn rocks. I looked at my map and saw a quick way over the hills to the northwest, which would take me to the highway in a matter of a few hours. I’d have to bushwhack, and there might be a few bogs and beaver ponds along the way, but any amount of hard slogging was a cheap price to pay to get away from this cursed river. Still, I’d better get myself around a good breakfast first – a couple of chunky little brookies, caught on a human-tied, unmystical fly for a change. I went over to where I’d left my rod case leaning against a rock the night before.

The rod case was opened. The rod stood assembled. The line threaded bright yellow through the guides to the tip-top. The leader led down to the keeper ring. Cinched in it, snug and bright, was Ephemerella incognita.

Again I fled, to the limits of the island. I may well have been gibbering to myself as I ran. I skidded, half fell down through the sharp granite rubble to the water’s edge. My reflection shone, unwavering, on the still, cold water. I looked down, dreading what I would see.

The face of the dead angler stared up at me from the mirror of Wendigo Brook. The grizzled gunfighter’s mustache wavered, shimmered in the current, the pale eyes stared up into mine – dead at first, then with growing recognition. The face I saw was my own . . .

This story also appears in A Roaring in the Blood, which features 15 of Robert F. Jones’ best stories. Order your copy today!