Deep down, he knew this duck, this day, no matter how good it had been, could not have made up for the things they had already lost.

As they turned off the main highway onto a rutted two-track, Tom glanced over at his son and wondered what Casey would be thinking. There were a million questions he wanted to ask him. Did he recognize the road? Was he excited about his first real duck hunt? And when had he gotten so big?

As they turned off the main highway onto a rutted two-track, Tom glanced over at his son and wondered what Casey would be thinking. There were a million questions he wanted to ask him. Did he recognize the road? Was he excited about his first real duck hunt? And when had he gotten so big?

He thought of asking Casey, but instead he just continued driving and hoping that the west wind would continue blowing, and the ducks would still be in the same pond, and that no one else would beat them there, and that Casey would like the new shotgun, and that every single thing would be absolutely perfect.

It had to be.

This was the first time he’d seen Casey in almost a year; the first time his son had been back to North Dakota, back home, since he and his mother moved to Californian early two-and-half years earlier.

“Remember this road?” he finally asked, looking over at his son and forcing a smile.

Casey looked around for a moment and shook his head.

“Huh-uh.”

No! How could you not remember? Tom wanted to yell. We used to come here all the time when you were a kid. This was our road.

“How ’bout that slough; I know you remember that.”

“It all kinda looks the same, you know. Forgot how flat it was up here.”

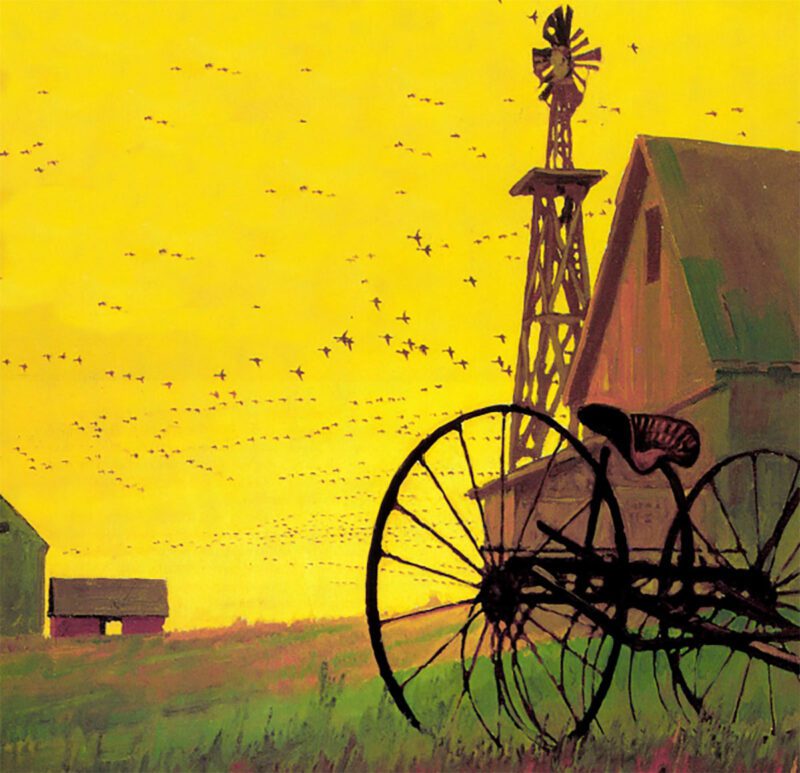

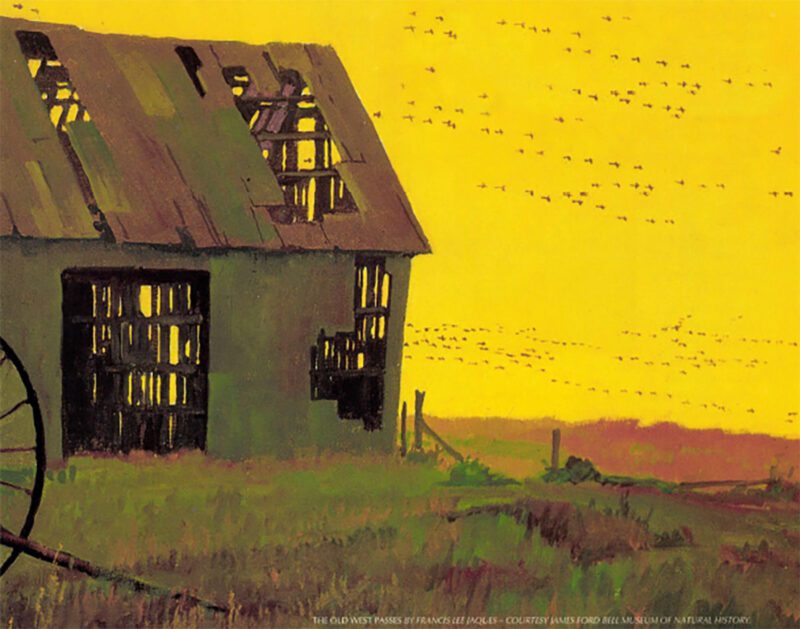

Tom looked around. He’d never thought of it as being flat before. It was home. But looking around now, and thinking of the lush, rolling mountains where Casey lived, maybe it was kind of flat. In every direction the prairie seemed to roll on forever, the monotony of the farmland broken only by the occasional pothole or shelter belt.”

Your uncle Dale and I hunted this slough opening weekend and got our limit of mallards and honkers in an hour,” said Tom, pointing out Casey’s window. ‘We were set up on that point right over there. You’da had a blast.”

Casey looked over at the pond for a moment and nodded.

“Huh.”

Like he cared, Tom thought. Ducks and me and shotguns and home had probably been the furthest thing from his mind out there. Or had they? Casey hadn’t said much since that morning when he picked him up from his grandma’s house. He didn’t even really know if his son wanted to be here.

He had found out Casey was coming a month earlier. Cindy had called to tell him she needed to return home to see her parents for a weekend, and she was blinging Casey. “You might take him out duck shooting or something,” she had said. “He passed his hunter’s safety class this year, you know.” It seemed like something he should know, but didn’t. That’s kind of how things had been lately. He usually had to find out things like Casey making the all-star team or learning to fly fish from his grandparents, or from Casey’s mom. He stole a glance at his son, still amazed at how much he’d grown … and how far they’d grown apart from each other.

It hadn’t always been like that, though. They talked a lot right after he and his mom left, almost every day. Casey would even call him on occasion. But gradually, the conversations became less frequent. Casey made new friends, took up new hobbies, and Cindy’s boyfriend Ted seemed to fill the void he had left. When Cindy called to tell him they were coming, he realized he hadn’t spoken with Casey in more than a month.

“How’s football going?” he tried again.

“Fine.”

“School?”

“Good.”

Although they were finally together, their conversation so far seemed a lot like their phone calls -a lot of one-word answers and awkward pauses. At first he thought one day didn’t seem like much time to make up for a whole year, but the way things were going now, one day might feel like a year.

“How ’bout your mom and …

“Fine. Everything is just fine.”

Tom could hear the frustration in his voice. He had promised himself he wouldn’t try to force his way back into Casey’s life in just one day; that he would just by to have fun with him and hope that was enough. He was banking on a great day in the duck blind to make everything all light and he’d done everything he could to ensure the hunt would go smoothly. He had been out scouting every night that week and watching the weather channel religiously. It had been a wet summer and the ducks had been scattered in small flocks for most of the fall. But a cold snap the week before had frozen many of the smaller ponds and now, most of the divers had headed south and the mallards were concentrated on the bigger marshes. Just like the weathermen had said, the west wind started blowing on Thursday and hadn’t let up in two days. The marsh they were headed to was deep enough in the middle that it hadn’t frozen yet. He had come out the night before and built a small blind and then watched until sundown as hundreds and hundreds of mallards funneled in after feeding in the nearby stubble fields.

God, I hope it didn’t freeze last night, Tom was thinking to himself, when suddenly Casey reached over and touched his arm. “Look,” he said, pointing out the window. Tom didn’t look right away. Instead, he stared down at Casey’s arm on his.

In the short brown grass beside the road were a dozen heads bobbing up and down. “Partridge,” he said. “Good eye, son.”

“Huns,” Casey added proudly. “Can we shoot ’em? The season’s open isn’t it?”

Tom didn’t want to tell him that he hadn’t shelled out the $95 bucks for a nonresident upland bird license.

“Nah, we’ll let ’em be. We’re a little late as it is and we need to get our decoys set up while the ducks are out feeding.” He could see the disappointment on his son’s face . “Maybe on the way home,” he added.

The west wind was building, and the truck rocked gently back and forth as they continued north. Casey slumped down in the seat, obviously disappointed about the partridge. Tom was still considering turning mound when they crested a low hill and he saw the ducks just a moment before Casey said, “Holy crap, I mean holy cow. Look at all the …”

Tom smiled at Casey’s enthusiasm. Johnson’s Slough was always one of the last to freeze, and its proximity to the road made it a popular place for hunters more interested in shooting ducks than hunting them.

“Always a few in Johnson’s,” Tom said, slowing the truck as they drove by. “Mostly gadwalls and spoonies, though. We’re gonna go get some real ducks – mallards and pintails.” Casey pressed his face against the glass as they passed. “Can we go get ’em? It’s not posted.”

Tom shook his head and smiled. “Nah. We don’t want to jump-shoot ’em. We’ll go get our decoys set up.” He laughed again at the thought of it.

“C’mon, please. We could sneak light up to the edge there.” Casey pointed out the window and then turned to him with eyes Tom hadn’t seen in years. He hadn’t planned on this.

Casey turned back to the pond. ‘We could get light up on ’em.” He was right, Tom thought. It was an easy sneak. He’d done it hundreds of times with his own dad when he was Casey’s age.

“They’re just gadwalls and some spoonbills, though,” he pleaded. “Wouldn’t you rather shoot a mallard for your first duck?”

“I don’t care.”

Tom looked over at his son for a moment. Why would he care? At his age, a duck’s a duck. Tom slowed the truck and looked back at the pond. The ducks were huddled up on the lee side against the tall cattails. It would be easy, he thought again, as he glanced down at the clock on the dash. They were late already, but the ducks had been feeding late and with this wind, they would be flying all day. It wouldn’t take more than ten minutes to run down and blast one and be back on their way. He glanced over at Casey again. His face was still pressed against the window.

“Ah what the hell,” Tom said and his son turned to him and smiled.

“All right!”

“But we gotta hurry. I’ve got a great mallard shoot lined up just a few miles up the road.”

He continued driving until they topped a small hill where the truck was out of Sight and then pulled over. Casey stepped from the truck and was busy pulling on his hat and gloves when Tom reached behind the seat. “Well, I guess now is as good a time as any,” he said, smiling as he handed his son the new gun case.

Casey studied it for a moment and then blurted out, “For me?”

“Go ahead and open it.”

Casey hastily unzipped the case.

“It’s a 20,” Tom said. “Nice and light. Just like the one I started with.” His son’s face lit up when he saw it. “Remington,” he said. “This is the same kind Ted has!”

Tom bit his lip for a moment, then forced a smile. “Should be a good one for you. You know how to load it?”

“Yeah, they showed us in class,” said Casey, grinning. Tom handed him a box of shells and Casey ripped open the top and pulled out three shells. “Is it mine … to keep I mean?”

“You bet,” Tom said. “But you might have to leave it here. ‘We’ll see what your mom says. “Casey held it up against his shoulder. The big gun looked awkward in his small arms. Tom forced a smile, wondering if he had just given his son a gift, or if he’d just made his first attempt at buying him back.

“Pow. Pow,” Casey repeated over and over again.

“Throw this on,” Tom said, handing him a new goose-down camouflage jacket. ”I’ll slip into the waders.”

As he reached for the green duffel bag, he looked up at Casey who was putting on the new jacket. His expression reminded Tom of the Christmas they’d spent together.

“Hate to put these things on,” he said. “But Molly’s still a little sore after the surgery, so I thought I’d let her rest another week. Just try to shoot one close to shore, so I don’t have to go in very deep.”

Tom looked over at Casey who was still swinging the gun around and whispering “Pow.” He hadn’t heard a word he’d said. When Tom had the waders on, he walked over to Casey. “Ready?”

“Aren’t you gonna bring your gun?”

“Nah, there’ll be plenty more. But we need to hurry so we can get set up at the other pond before they start coming back in from feeding.”

“All light,” he said and smiled. “Thanks for the gun.”

“You bet, son. Let’s go see if it works. We’ll circle around this hill and come in from over at the far edge. If we stay low, we should be able to get right on top of them. Okay?”

“Yep.”

Tom smiled as Casey slowly closed the door, being careful not to slam it. The ducks were out of Sight, but still Casey crouched low as he walked. They cut through a dry gully of short pasture grass and then started angling toward the cattails surrounding the pond. As they crept along, the incessant quacking grew louder. Tom looked down and saw that the water was already up to his shins. He hulled back to Casey, who was up to his knees and grinning.

They took a few more steps, then suddenly the pond went silent. Tom turned to Casey and mouthed the words, “Get ready.”

Through the cattails, Tom caught the beady eye of a drake mallard just a second before the pond erupted. There were even more ducks than he had imagined. The mallards had been tucked light up against the reeds and he hadn’t seen them. He pointed to them and hollered, “Take ’em son.” He waited for a few seconds and then said again, “Take ’em Case.”

More and more ducks continued to emerge, but still no shot came and finally he looked over and saw the big barrel wobbling in the air and a look of mixed fear and excitement on his son’s face.

“Dang. The safety,” he heard Casey say and saw his finger slide it to the side. Even the spoonbills and mud hens were almost out of range when the shot fin ally rang out.

Casey let the gun down and they both watched in silence for a moment. The ducks turned and began heading out when suddenly one straggler dropped out of the flock and sailed down toward the water.

“I got him!” Casey cried out. “That’s the one I was aiming at.”

He looked up at his dad. “I got him. I got him. Did you see him fall?”

Tom watched as the drake gadwall splashed down and immediately dove, a hundred yards away, in the middle of the cold, murky waters of Johnson’s Slough. He stared out across the empty water For a moment and then looked over at his son, who was holding his gun up in the air.

“Did you see him fall? He was a long ways out, huh.”

“He sure was,” Tom said and forced a smile. “It was a nice shot, son.”

Now what? he asked himself. Johnson’s Slough was deep — over his head in some places. He’d learned that the hard way.

“Let’s go get him. I wanna see him.”

Tom studied his son for a moment. Of all the times he’d imagined this moment, it had never happened quite like this.

“Let’s go get him,” Casey said again, with the kind of confidence Tom hadn’t known in years.

“Well,” said Tom, “that might not be all that easy. He’s kind of in a bad spot, son. It’s too bad we don’t have Molly.”

“We’ll get him. I think I hit him pretty good.”

“You see, son. He’s out pretty far and I don’t know if…” It was no use. “Well, let’s go walk around to the other side and see if we can get another crack at him”

“All right!”

They skirted the edge of the pond, looking out over the water that was now sitting to whitecap in the driving west wind.

“What kind is he? Could you tell’?”

“Looked like a gadwall,” his dad said, still staring out over the water.

“Can’t wait to show him to mom. Maybe we can get it mounted, huh?”

“We’ll see,” Tom said. “Keep an eye out for him and get ready to shoot again.”

“Oh I’m ready,” Casey said.

Their first trip around the pond yielded the same result as the next four. Every once in a while, Tom would look to the west toward the other panel. Even from Johnson’s he could see wave after wave of mallards pouring into the narrow channel where he had planned to set his decoys. An icy rain had started to fall and he pictured the two of them hundred up beside each other in the blind he had built the night before. Perhaps, he thought, if they headed over right now and got into a great shoot, Casey might forget about all this. Afterall, he thought, it’s just a damn gadwall.

He glanced over at Casey who was still clutching his new gun in the ready position. It wasn’t just a gadwall to his son, and with each unsuccessful trip around the pond, it was becoming something more to him as well. He imagined Casey telling his mom, and Ted, about what had happened. How his dad had left the dog at home; how he’d given lip and left his first cluck to die out in the pond; how he never wanted to hunt again.

“There he is!” Casey cried out. “Right there.”

Tom glanced at where he was pointing and saw the gadwall swimming with its head down 30 yards out.

“Shoot him, son.”

Casey lifted the big gun up and tried to steady it as the duck swam farther and farther away. “Shoot,” Tom said, just a moment before he heard a “click” come from the gun. “Nuts!” Casey cried. “Forgot to put a shell in.”

Tom looked out at the duck and then reached for the gun. “There, let me have it,” he said and pulled the shotgun from Casey’s hands. But the force of it knocked his son off balance and he tripped over a sunken log and fell. Tom quickly reached down to pull his son out of the muddy water.

“Are you okay, son? Are you okay?”

Casey looked down at his new jacket that was now soaking wet, and nodded. “Yeah, I’m all right.”

Tom pulled his son into his chest and wrapped his arms around him, holding him there for several seconds. He didn’t want to let go. Finally, he heard Casey whisper, “We’re not gonna get him, are we?”

Tom pulled back and stared into his son’s eyes for a moment. Then both of them turned and looked out over the water. “It’s not looking too good, son. He was headed out to that island in the middle. That’s pretty deep out there.”

Casey looked out toward the small island. “What’ll happen to him?”

Tom shook his head, trying to come up with something fatherly to say, but then just looked at Casey and sighed, “I don’t know, son.”

Casey gazed down at the water that was lapping at his knees. When he finally looked up, Tom saw that there were tears in his eyes. He wanted to say something like, “that’s just the way it goes sometimes,” or “that’s why they call it hunting,” but he knew it would be wasted breath. He glanced at his watch and then out toward the island again. Casey was shivering now and he could hear his teeth chattering.

“It’s getting late, son. Why don’t you head back to the truck and get out of those wet clothes. The keys are on the dashboard and there’s some hot chocolate in the thermos under the seat. Go ahead and turn the heater on. I’ll just take one more walk around the pond and then we better be getting home.”

“All right,” Casey shrugged, and slowly began slogging toward the vehicle. Tom watched him until he was out of sight and then turned and looked off toward the whitecaps that were lapping at the small island in the middle of Johnson’s Slough.

He hefted his son’s new gun and wondered if it would ever be used again after today. The icy rain was now turning to snow and he could feel the biting wind against his skin as he began circling the pond one last time. With each step, he could feel his heart sinking deeper and deeper into the muddy bottom of Johnson’s Slough.

Maybe he would just forget about it, Tom thought. Maybe he’d come back again next fall and they could start all over again. But maybe he wouldn’t. He didn’t know Casey well enough anymore to know how he would feel next week, let alone next fall. He didn’t even how he was feeling right now. But he had a pretty good idea.

What he did know was that the last few years without Casey had taught him he would have done some things differently if he could do it all over again. He would’ve gone to more of those little league games he never had time for. And he would have taken his son camping more often. He would’ve taken more photos and hugged him more often.

But it was all just water under the bridge, and deep down, he knew this duck, this day, no matter how good it had been, could not have made up for the things they had already lost. He was shivering as he sat down in the grain stubble and began pulling off his waders. He had to start somewhere. The gap between he and his son had grown as wide as the one between him and the small island in the middle of Johnson’s Slough.

The sun was almost down when he finally reached the truck. He thought about Cindy and how upset she would be. She would never understand. As he slowly opened the passenger door, he hoped that someday Casey would.

His son was sleeping on the seat, covered up by his new jacket that was still dripping on the floorboards. At the sound of the door, Casey’s eyes opened just long enough for him to mumble, “Hi, dad,” and then he quickly fell back to sleep.

That his son hadn’t noticed he was half-naked or that an inch of new snow had fallen didn’t matter. He stood there with the door open for several minutes trembling, with tears in his eyes, trying to remember when the last time he’d heard his son call him “dad.”

That his son hadn’t noticed he was half-naked or that an inch of new snow had fallen didn’t matter. He stood there with the door open for several minutes trembling, with tears in his eyes, trying to remember when the last time he’d heard his son call him “dad.”

Finally, he leaned over and whispered, “Thank-you,” and gently placed the duck on Casey’s lap.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2005 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

An intimate and illuminating glimpse at Ernest Hemingway as a father, revealed through a selection of letters he and his son Patrick exchanged over the span of twenty years. Buy Now

An intimate and illuminating glimpse at Ernest Hemingway as a father, revealed through a selection of letters he and his son Patrick exchanged over the span of twenty years. Buy Now