In early June of 1844 Captain John Coffee “Jack” Hays and his 14 Texas Rangers were scouting for Comanche raiders some 80 miles from San Antonio along the Pedernales River. After setting up camp near Walker’s Creek, one of the Rangers spotted a bee tree and began to climb up toward the hive. What greeted him, however, was not a swarm of angry honeybees, but something far more frightful: the sight of some 80 Comanche warriors riding toward the Rangers’ camp.

After quickly saddling up and forming a line, the Rangers were met by a party of Comanches who began to shout insults in Spanish, taunting the small band of Rangers to attack.

A veteran Indian fighter, Capt. Hays didn’t fall for the ploy. He figured that the bulk of the war party had moved to a hill a few hundred yards behind the band of Comanche riders and had by now formed a defensive line well-protected by boulders and trees.

A frontal assault would be a deadly folly, so Hays led his men forward cautiously and, coming upon a dry ravine, used it as cover to ride around the hill and back up the far slope to gain a position behind the enemy line. Hays now had two classic tactical advantages: He commanded the high ground and he could attack the enemy’s rear.

It was a third advantage, however, that bolstered the Ranger’s confidence even more. It was an ace in the hole that would make all the difference in how their hand would play out in what would soon be a bloody, close-quarters engagement.

Young Samuel Colt had a curious mind and an adventurous spirit. His original biographer notes that in 1821, at age seven, he disassembled and then properly reassembled a pistol of that era. To satisfy his wanderlust, he persuaded his father to let him go to sea at the age of 16, an experience that would prove pivotal in his young life.

Working for his passage on the brig Corvo bound for London and Calcutta, it’s believed that the ship’s capstan, essentially a drum-shaped device that rotates in a horizontal plane around a vertical axis to wind a ship’s anchor cable, provided Colt with the visual inspiration for his revolving cylinder concept. From this trip he returned home with a carved wooden model of his simple, but revolutionary idea.

With prototype revolvers built from his model, Colt received a U.S. Patent on his invention in 1836 and that same year chartered the first Colt firm, The Patent Arms Manufacturing Company in Paterson, New Jersey, then one of America’s leading manufacturing centers. At age 22 Sam Colt was in the firearms business.

Hopes for strong sales to the U.S. Army were dashed when the Ordnance Department determined Colt’s five-shot revolver too complicated for service use. The Republic of Texas deemed otherwise and did purchase a number of Paterson firearms, including 180 of their No. 5 Holster pistols. Overall sales, however, were not enough to keep the company afloat and in 1842 its doors closed for good. Before he was 30, Sam Colt found himself out of the firearms business.

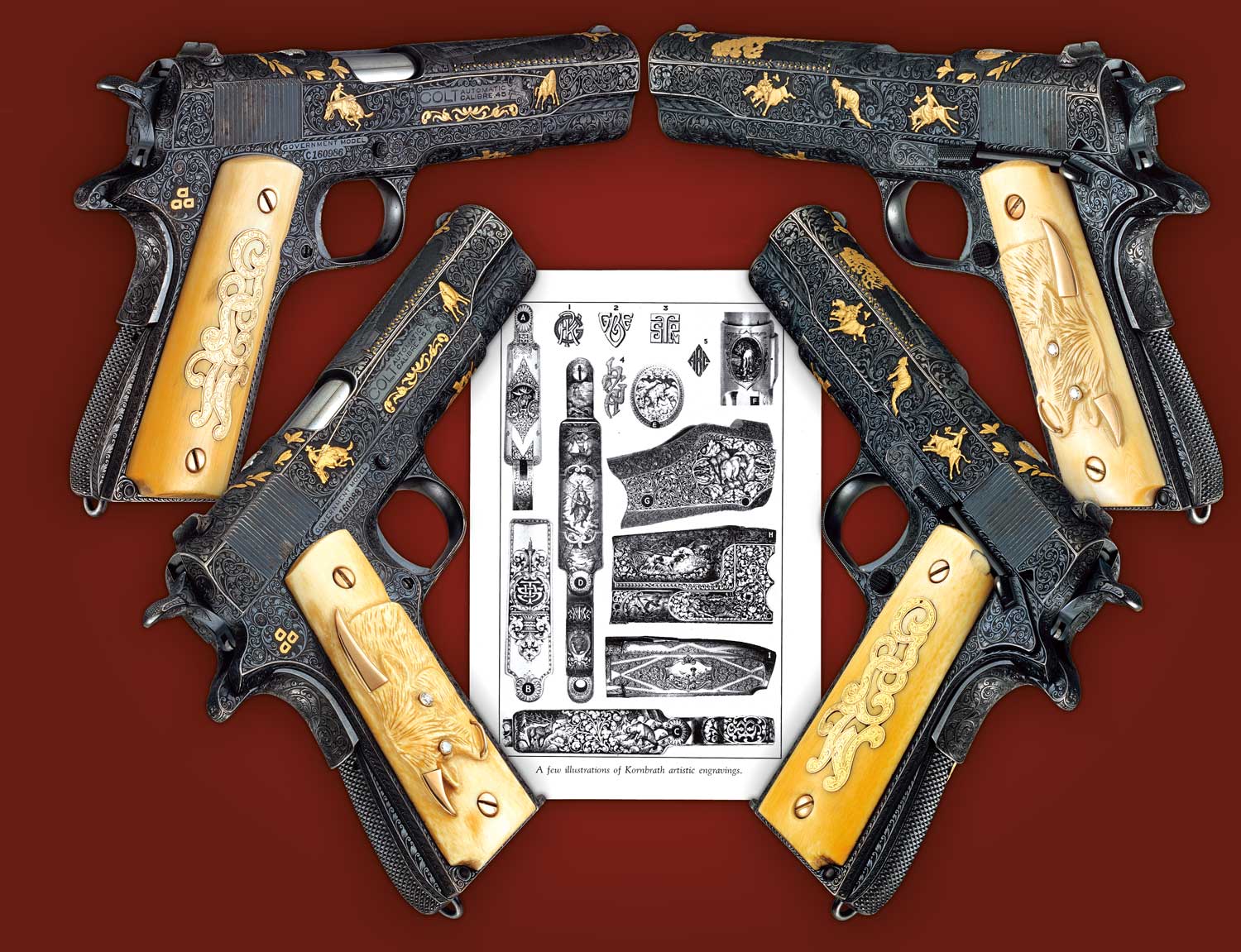

Colt Model 1911A1 Semiautomatic pistols. Their hand-cut ivory grips showcase gold and diamond mountings.

Captain Jack Hays knew the Comanche war party hidden at the bottom of the hill greatly outnumbered his small band of riders. Hays also knew that his entire company of Rangers was, for the first time, armed with five-shot Colt Paterson revolvers. Now his men could fire multiple shots while staying mounted and moving on horseback, a critical edge when confronting warriors known for their ability to let arrow after arrow fly from their short bows while riding full tilt.

In a wedge formation, Captain Hays and his men drew their Patersons and charged down the hill.

In just over an hour of fierce combat, the Indian casualties at what became known as the Battle of Walker’s Creek were estimated from 20 to 50 killed and wounded, while Ranger losses amounted to one dead and a handful wounded.

In the widespread national press that trumpeted their surprisingly one-sided victory, Hays and his Rangers lauded the effectiveness of their multi-shot Paterson revolvers. While from a military standpoint the Battle at Walker’s Creek was more of a skirmish than a full-fledged battle, it would become a critical turning point in the history of firearms manufacturing in America.

Produced in 1872, this Tiffany-gripped Colt Model 1862 Conversion features bronze handles by Schuyler, Hartley and Graham.

The strong endorsement from men who had fought and won in battle with his Paterson revolvers was the kind of dramatic and highly publicized event that Sam Colt needed to get back into business. In 1846 Capt. Sam Walker, a Ranger who had fought with Capt. Jack Hays, came east, and then serving with the U.S. Army, began to work with Colt to improve upon the original Paterson with a heftier and larger caliber revolver for mounted troops.

This new Colt, a six-shot in .44 caliber that weighed a beefy 4-pounds, 9-ounces, quickly found favor with the Army and an order from the Ordnance Department for 1,000 of these new-style revolvers was placed in 1847. With prototypes in hand but no factory to produce the revolvers, Colt turned to Eli Whitney Jr., then a contractor for Army muskets, to make them for him. Whitney agreed and Sam Colt, still a young 33, was back in the firearms business.

Sometimes, all you need is a second chance.

While the winds of fortune had shifted in Sam Colt’s favor, it was an ill wind that soon greeted Capt. Sam Walker. Just a few months after returning to active duty, he was killed in the Mexican War at the Battle of Juamantla in October 1847. It was only a few days before his death that he had received a pair of the new Colt revolvers, a gift from Sam Colt. Upon the captain’s death, Colt named his new revolver, the Walker Model.

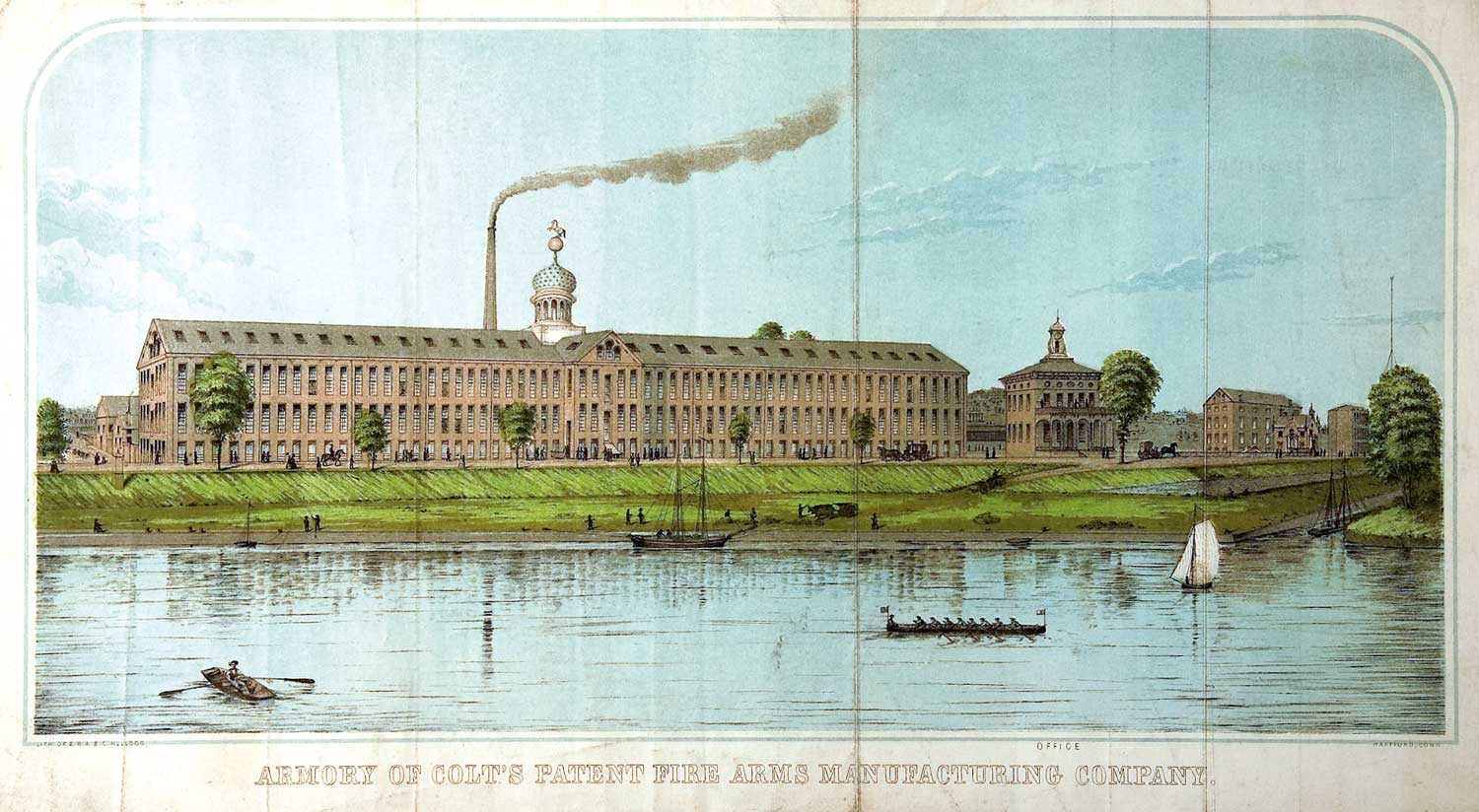

Early lithograph of Colt’s Armory in Hartford along the Connecticut River.

Before the end of 1847 Colt had leased a factory in Hartford, Connecticut. With the success of the Walker and a succession of new and improved revolvers, sales to the military and civilian markets soared.

With his business growing, Colt began to buy land in Hartford along the banks of the Connecticut River. In 1855 Colt’s new factory, the Armory, was completed on his riverbank site and, when it opened in August of that year, was praised by the Hartford Times as “The greatest individual enterprise ever attempted in this country.”

The roof of the Armory was adorned with an onion-shaped blue dome supported by white columns and crowned by a golden sphere. Perched atop that was a rampant colt holding a broken spear. Like an outsized and blazing neon sign of its time, the bright blue dome dominated the city’s skyline and embodied Colt’s showmanship character.

While the original dome perished when the Colt factory burned down in 1864, a new dome commissioned by Colt’s widow when the factory was rebuilt stands today, a poignant reminder of when Colt Armory and the city of Hartford were at the forefront of a manufacturing revolution in America.

At the midway mark of the 19th century, our nation was on the cusp of rapid and dramatic change. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 and successive waves of homesteading pioneers quickly pushed the country’s frontier past the Mississippi River. Emerging manufacturing technologies were about to make large-scale production on factory floors possible, and traditional New England towns began transforming themselves into burgeoning industrial centers, manned by the nation’s fast-growing immigrant population.

From the age-old system of hand-built goods fashioned by local craftsmen or workers in cottage shops, low-cost, mass-produced products were on the verge of opening the door to national, even international, markets for America’s industrial entrepreneurs.

Sam Colt was a man poised to take full advantage of these new opportunities. A pioneer in mass production techniques, Colt was the first manufacturer to introduce the widespread use of interchangeable parts that could be put together on a factory assembly line. With its strong focus on new technology, the Colt Armory became a breeding ground for several generations of engineers and machinists, men who would have a significant impact on American manufacturing techniques in a wide range of industries in the decades ahead.

Although Sam Colt’s formal education was limited, he exhibited a natural talent not only for employing modern manufacturing methods, but also in the then nascent skills of marketing and public relations. He was, if you will, a Thomas Edison, a Jack Welch and a Donald Trump all rolled into one.

Colt had a highly curious and inventive mind; he intuitively saw the value of good management principles and was by nature a colorful and creative promoter of himself and his products.

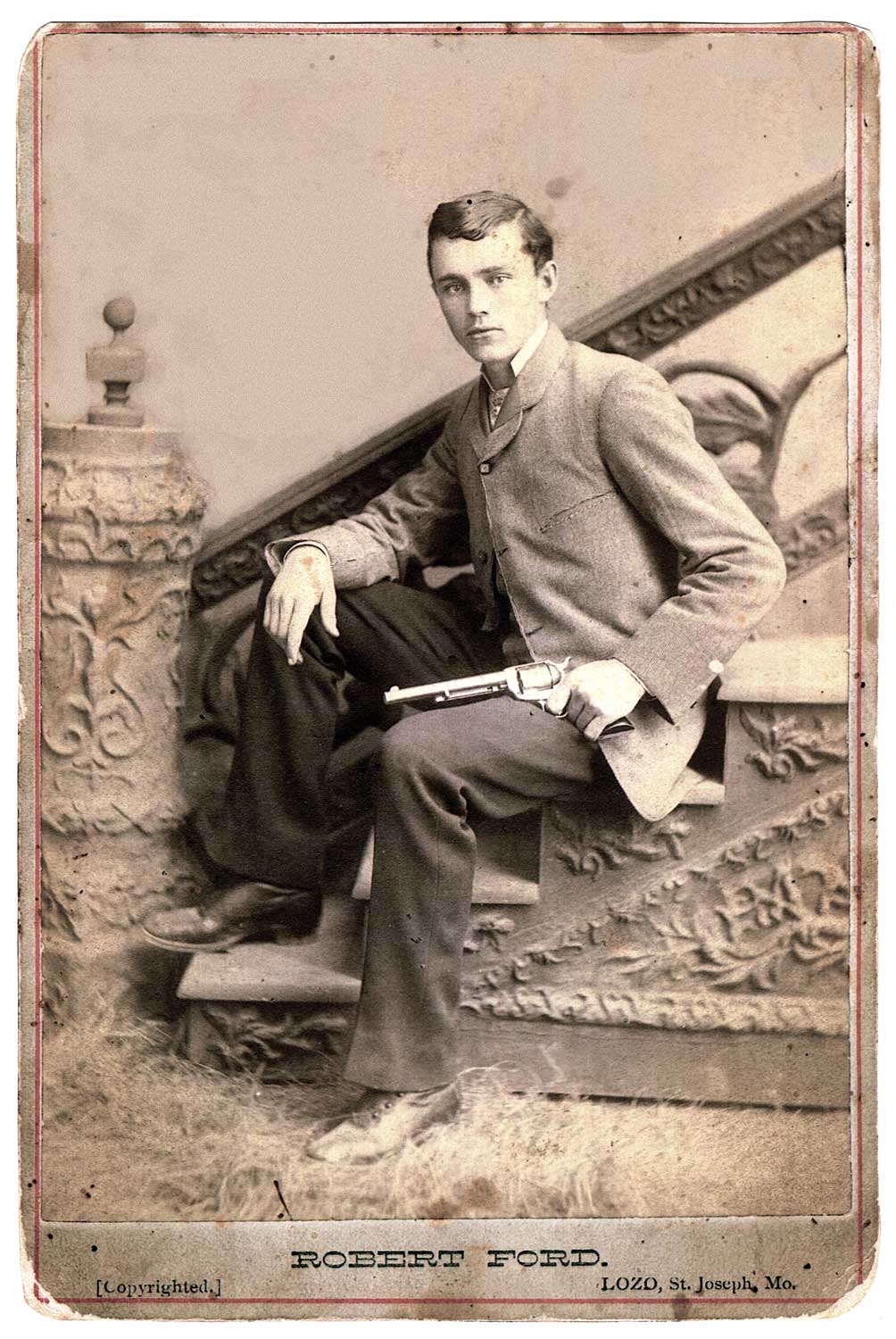

Robert Ford, who along with his brother killed the outlaw Jesse James, holds a 71/2-inch Single Action Army with a nickel finish.

The flood of pioneers and gold-seekers pushing west opened a rapidly expanding domestic market for firearms while unrest overseas spurred Colt to branch out into international sales. Years ahead of his time, Colt was the first American manufacturer to open a plant abroad. While ultimately not successful, Colt’s overseas plant, built in London on the banks of the famed Thames River, helped supply more than 30,000 revolvers for the Crimean War (1854-56) and played an important role in creating a high regard for Colt firearms throughout Europe.

With strong factory management in place, Colt spent much of his time as the company’s number one salesman and lobbyist. Whether they were in the military or government, Colt knew the importance of cultivating friends in high places and he was not shy about presenting such men with beautifully engraved and sometimes gold-inlaid Colt revolvers. Exquisitely crafted presentation guns were given to heads of state from around the world, including Czars Nicholas I and Alexander II of Russia, King Frederick VII of Denmark and King Charles the XV of Sweden (the latter two were gifts from President Abraham Lincoln).

The company also showcased elaborate displays of Colt firearms at international fairs. At London’s 1851 Great Exhibition of Art and Industry, the Colt pavilion featured some 450 guns, a display that still overshadows the exhibits of even today’s largest firearm companies.

Colt Single Action Army revolver with automatic ejector.

Colt spent considerable time in Washington, D.C., gaining endorsements for his guns from prominent and respected military leaders while seeking out field officers to act as Colt agents. For the civilian market, the company employed a cadre of traveling salesman as well as some 15 to 20 wholesalers who supplied firearms retailers. In an era when competition among manufacturers with similar product lines was heating up, Colt seemed to instinctively sense that publicity and marketing were just as necessary to success as building a better mousetrap.

While revolvers were the company’s signature products, Colt also manufactured a full line of long guns, notably their Model 1855 Sidehammers, which were available in rifle, carbine, rifled musket and shotgun configurations.

In the turbulent years just prior to the Civil War, the Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Co. had risen to the top tier of American armories, and the company’s products had established a level of renown that was the envy of its competitors.

By his early 40s Colonel Sam Colt (a commission given to him by Connecticut Governor Thomas Seymour) had gained both widespread fame and a sizeable fortune. Reports indicate that Colt’s personal income in 1860 and 1861 was more than $1 million per year, a staggering sum considering that the typical factory worker at that time earned $240 a year.

Colt, however, was not a man to stop and “smell the roses.” Indeed, his success seemed to spur him to push even harder. He maintained a practically non-stop work schedule, whether on the road or in his Armory office. Weakened over time by previous bouts of rheumatic fever, a physically exhausted Sam Colt died on January 14, 1862. He was only 47.

Colt Single Action Army that is one of a matched pair, each with gold inlays ad intricately carved ivory grips.

From a business perspective, Colt’s rise had been meteoric. In the span of just several decades he had become not only one of America’s best-known inventors and wealthiest manufacturers, but also, through his unflagging promotion, had put a stamp on his products that was unprecedented at the time. Indeed, his greatest legacy was the creation of one of the most widely recognized and enduring brand names in American history.

Upon his death, Sam Colt’s widow, Elizabeth, gained control of the company and committed herself to the Armory’s continued success. When the factory burned to the ground in 1864, Mrs. Colt did not hesitate to have the Armory rebuilt exactly as her husband had left it. Even with the devastating fire, Colt produced almost half-a-million firearms for Union forces during the Civil War period.

This gold-inlaid and engraved Model 1849 Pocket Revolver is one of only six in existence. Manufactured in 1854, the gun was presumably created for display at the Paris Exposition of 1855.

While the Colt Armory continued to develop handguns for the civilian market, including its popular five-shot pocket pistol and a line of derringers, the next major iteration of its revolver line was destined to become not only a symbol of the company, but of an American era. The Colt Single Action Army Model 1873, designed to use metallic ammunition that contained its own primer, was adopted that same year for Army service and quickly achieved an iconic role in the settlement of America’s still untamed West. Whether cowboy or frontiersman, lawman or outlaw, Colt’s “Peacemaker” rode on the hip of both the famous and infamous, from Wild Bill Hickok and Wyatt Earp, to Billy the Kid, James Younger and the Dalton boys.

By 1877 Colt had begun production of double-action revolvers, a line that eventually became a mainstay of the company and spawned dozens of variations for military, law enforcement and civilian use. Shortly after the turn of the century, however, an altogether different type of handgun would add another legendary model to the company’s lineup and become its all-time best-selling handgun.

Designed by John M. Browning, the Colt Model 1911A1 .45 ACP was the first semi-automatic pistol to be adopted as the U.S. Military’s standard handgun. Serving with distinction until 1984, no other firearm has had a longer history with our military. Civilian models quickly became a success as well and today, more than 100 years later, the 1911 remains a gold-standard against which other automatic pistols are judged.

Despite an all-out production effort by the Colt Armory during World War II, there was little cause for celebration when the war ended. In its early days the Colt factory had been America’s showcase for state-of-the-art tooling machinery and innovative assembly methods. Now, after resting on its “production laurels” for nearly a century, the Armory had become an obsolete and inefficient plant. In the decades ahead the company’s failure to modernize combined with growing labor unrest among its workers and a series of management miss-steps created an uncertain and, at times, a bleak future for Colt.

From top: Walker Civilian Model, Military Walker, Transition Dragoon, “Reduced Weight” Dragoon and Third Model Dragoon from a cased pair.

A bright spot did occur in 1961 when Colt acquired the rights to the AR-15 Rifle from the Armalite Division of the Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation. As the war in Vietnam rapidly escalated in the early 1960s, Colt went into full-production of the military version of the M16.

While defense contracts were a boon to the company, the loss of the M16 business in 1988 put the future of Colt at peril. It was not until new management came in 2002 and rebuilt its defense business that Colt was finally back on a solid track. The strong focus on military production did, however, cause the civilian side of its business to languish. In 1999, for example, after more than a century, Colt announced the end of its production of double-action revolvers.

As the new century began, some believed that Colt might abandon the civilian market altogether. By good fortune, by design and by a still strong measure of the “magic” in the Colt name, quite the opposite occurred.

In little over a decade the AR-15 platform rifle, today called the Modern Sporting Rifle (MSR), has become by far the most popular rifle in the U.S. The Colt 1911 continues to be a favorite among both veteran and new hand-gunners and, almost a century and a half later, the Colt Single Action Army remains an American classic. It’s hard to think of any other three firearm models that have enjoyed the same staying power in the marketplace.

Underscoring the popularity of these firearms, a number of companies here and abroad now manufacture their own versions of these three classic Colts. For Colt, that’s resulted in a lot of head-to-head competition. Very much on the plus side, however, it has reaffirmed among discerning gun-buyers the value and desirability of owning the real McCoy.

In this early daguerreotype two gentlemen pose with their Model 1849 Pocket and Model 1851 Navy revolvers.

The hallmark of Colt craftsmanship can still be found in its Custom Shop. Here you can order the Colt of your dreams. Is there a more quintessential American firearm than an exquisitely engraved Single Action Army revolver?

With a handful of iconic consumer models (and a centerfire rifle in the offing), Colt is building a new base in the consumer market. The company, however, has not forgotten its historical roots. At a time when so many great brands have become as shallow as a roll-mark, quality and craftsmanship still run deep at Colt. Simply put, a Colt is still a Colt.

Sometimes, all you need is a second chance.

Every image in this article is from The Art of The Gun – Magnificent Colts, a stunning two-volume set featuring selections from the Robert M. Lee Collection of Colt firearms and paraphernalia. Coauthored by Lee and R. L. Wilson, these spectacular books feature 600 11×14-inch landscape pages, with hundreds of Colt pistols and revolvers reproduced actual size.