That’s about as far as I could narrow it down.

The truth is, there are precious few encounters with Perfection in a person’s life.

But they are there, and we must be ever vigilant for their presence and open to what they may offer.

They stay but for a moment, and then they are gone. Except of course for the memory.

They can come in any form – your daughter’s first breath, the first snow of winter, the silence of a high-desert sunrise, the sound of winter wind, or anything ever written by William Shakespeare or Ludwig von Beethoven or Guy Clark.

It is inevitable that such questions should arise from time to time, casually and without much consideration. Your best shotgun, best bird dog, best hunting trip. Your favorite painter, favorite poem, favorite Bordeaux, favorite Kafka short story. You get the picture.

But there are some things that perhaps shouldn’t be asked, for it is virtually impossible to speculate on such matters, much less come up with a cognitive response. At least it is for me.

Except of course when it comes to my best fish.

That one’s easy.

Winters are long when they’re lonely and cold. And even longer when they’re hot. And for him, that winter had the potential to get hot in a hurry.

I remember Christmas came on a Sunday that year, and I still had nothing to send him, at least nothing he might actually want or find useful.

All he really needed, he pretty much already had, at least in terms of material goods. People would ask, but I had no substantive answers for them, at least none that I could actually divulge.

Suffice it to say that fishing was not something he was going to be doing that Christmas. And most likely, neither was I.

Mind you, it’s not that I couldn’t fish; it’s just that I didn’t have the heart to do it. For you see, we had always fished together on Christmas, my brother Jack and me, somewhere, sometime. It might be on Christmas Eve or on Christmas Day or perhaps even on the day after Christmas. It might be up on Doe Creek or Laurel Fork or over on the Holston or the Clinch or the Watauga.

But at some point, we were going to fish.

But not this Christmas. Not this year.

We had last talked early Tuesday morning – at least it had been morning for me. At the time, both of us had been overlooking water, me sitting on a rock along a little creek that few people knew about, having just released a 19-inch rainbow trout, him eight hours ahead of me sitting low behind a barrier on a rooftop in Baghdad, overlooking the Tigris.

As far we could tell, only he and I and two others knew of this little creek where I now sat and about the big trout that came up into it from the lake in winter to spawn. He knew the run I was looking at, knew it better than I did – heck, he even knew the rock I was sitting on, and when I told him where a trout had just risen, he knew that too. We had caught them here before.

He had occasionally glimpsed fish of mysterious lineage out there among the runs and reeds of the Tigris through his spotting scope, and sometimes he’d even given some thought as to what flies and tactics might work on them. But times and tensions being what they were, he had never actually risked fishing there.

And so we had simply talked. I told him about my morning so far and that Mom had been doing just fine the evening before when I’d taken her a trout, and that I had nothing to send him for Christmas, and he said that was okay because he had nothing to send me either. And when the talking was done and we’d each stuffed our phones back into their respective safety pouches, I really didn’t feel much like fishing any more.

Christmas dawned bitter cold and empty. It had snowed during the night, unpredicted, a silent, windless snow, the kind that cannot help but ease even the most troubled spirit as it calms the woods and settles the streams. It was a soft, beckoning snow, one that comes a welcome gift when you really aren’t expecting it and therefore need it most, and for a moment I thought about my brother and our secret stream.

It was such an altogether unlikely little stream to be holding such large and secret trout. Jack had discovered it himself a couple of years before he’d left and had then taken me there.

Ordinarily this would have been a perfect morning to fish it.

But not this morning. Not without him.

So I just stood there unshaven in my old sweats and stocking feet, tom and ambivalent, peering out through the falling snow into the sleeping woods and trying to decide what to do with myself.

He would go. He would have gone without me. He’d told me as much when we had talked Tuesday morning. And now as I stood here arguing with myself, the first fragments of an idea began to take form.

So I got dressed and gathered up my fly rod and waders and old wooden net – and most importantly my camera. For I figured that if he and I couldn’t fish the stream together, at least I could show him what it looked like here on this cold Christmas morning in America.

In an hour I was there.

When I had last been here with my brother, it was January and ice was in the air and we had caught two big buck trout – one for our supper and one for our Mom. We’d carried them back up the steep trail shoulder to shoulder, him holding one end of the heavy stick around which we’d wrapped the stringer, me holding the other, and I don’t think either of us even came close to breaking a sweat.

Now alone, I began shooting photos as soon as I hit the narrow path that winds down beside the overgrown fencerow below the high meadows, across the little feeder creek and into the woods.

I meant to show him what the stream was like on this snowy Christmas morning, from the icy trailhead all the way down to the frozen lake.

I wanted him to wince at the frost in his nostrils and feel the ice peaks crunching beneath his feet as he tracked the frozen mud. I wanted him to slip across the glazed stones in the trail with me where it became too steep and forced me over into the crunchy, ice- encrusted leaves and to taste the hard chocolate we had once shared at the first bend where the trail meets the stream and to hear the dull thud that the frozen soles of our waders always made on the worn wooden planks of the old foot-bridge where now I paused.

The last time we’d been at this bridge together, I’d had the same old 6-weight that I carried now, freshly rigged and ready, the one we always seemed to share. We had swapped rods as we passed, and I had eased up the righthand side of the creek. Moments later he had yelled for me just as he’d hooked into that 24-inch rainbow when I was 80 yards upstream smack in the middle of the reeds, and he was already off the bridge and into the creek as I plowed in beside him. He had finally worked the trout to my net, and I had photographed them both as he carefully revived and released her.

Now I shot a photo for him from the bridge itself, peering straight down into the current, and then without really thinking all that much about it I made a single, idle cast into the head of the run.

It was one of those unseen, small-fish hits, just a light, pulsing tap, and when I struck, quite honestly I was thinking “ . . . creek chub.”

I swear I nearly yelled for him, as he had once yelled for me, when the line came tight and I saw the big trout roll, all dark and long and coral-sided as he shredded the surface before snaking back into the current. I headed off the bridge as Jack had done two years earlier, dumping the camera in the frozen leaves and stripping line while I picked my way across the big root tangle and into the fast water, somehow managing to maintain a light but firm tension from the rod tip to the fish.

Once in the creek and with my feet firmly planted, I reorganized my fly line and myself and turned to the task at hand. Again the big trout rolled and dove for the roots, then suddenly changed direction and bolted downstream. I moved with him, picking my way along the underside of the bridge and then out into the long tailing run, where I was finally able to get into position below him. Then he turned yet again and tore back upstream.

Now with the current in my favor, I applied only enough pressure to keep him centered above me and out of the roots. We eventually met just below the bridge, where I was able to orient him to the flow and finally lift the net around him, wishing desperately that my brother was here to see.

For a moment I just stood there, alone. We release most of our trout, but now I found myself wondering how long this one might keep in the freezer until Jack would be home and Mom could cook it for him. So I left the big fish in the net and made my way to shore, then carried him back up the trail to the foot-bridge where I laid him down next to our old fly rod and shot one more photo.

Oh, I continued on down the trail for a way, the trout hanging heavy from the rope wrapped around one hand and our fly rod in the other. But I never made another cast that day, instead shooting photos as I went, the last one showing the creek where it spills into the lake.

When I got home, I emailed the photographs to him in the same order I had shot them – except of course for the picture of the big trout, which I saved for last. I sent them in groups of three or four, including a message with the first email that read: “Thought you might like to see what the creek looked like this morning. Will try to give you a call at 17:30 tomorrow, Tigris time. Be well.”

As it turned out, things got ugly for him that Christmas day, and the communication links got pretty squirrelly, and it was three days before I was finally able to get the entire flight of photos emailed without them being bounced back. He told me later that they couldn’t have come at a better time.

I didn’t ask. There are some things you learn not to ask.

Like, “What was the best fish you ever caught?”

For my part, I sometimes think about that big red drum I once beached on a southwest wind in November in the booming surf just north of Cape Hatteras. And of course, I’ll always remember that late-October, hook-jawed chinook salmon from the Muskegon River in Michigan that was five ounces shy of 30 pounds and took me 200 yards downstream and from dusk into darkness.

Then there was the 40-plus-pound king salmon in Alaska, four miles upriver from the Bering Sea, that nearly broke my fingers when the handle on the screaming fly reel tore into them as the great fish began his second run.

But they and all the others pale in comparison to the perfection of a four-pound rainbow trout that came a gift from the Lord on His birthday to my brother and me.

One cold Christmas morning in America.

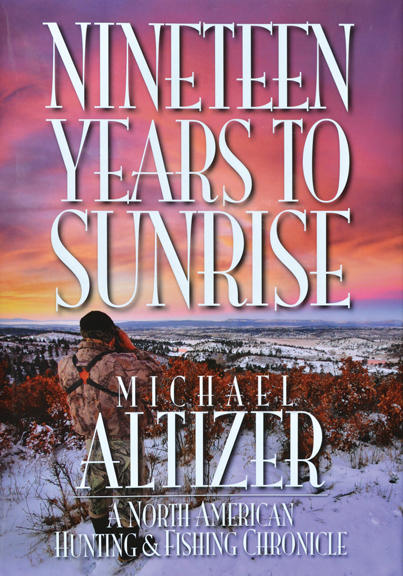

The Christmas Trout is one of 42 stories you’ll find in the pages of Michael Altizer’s Nineteen Years to Sunrise. Visit Sportingclassicsstore.com to purchase this and other Christmas gifts for the hunter and angler.