“To me, you should judge the painting by the emotion it creates.”

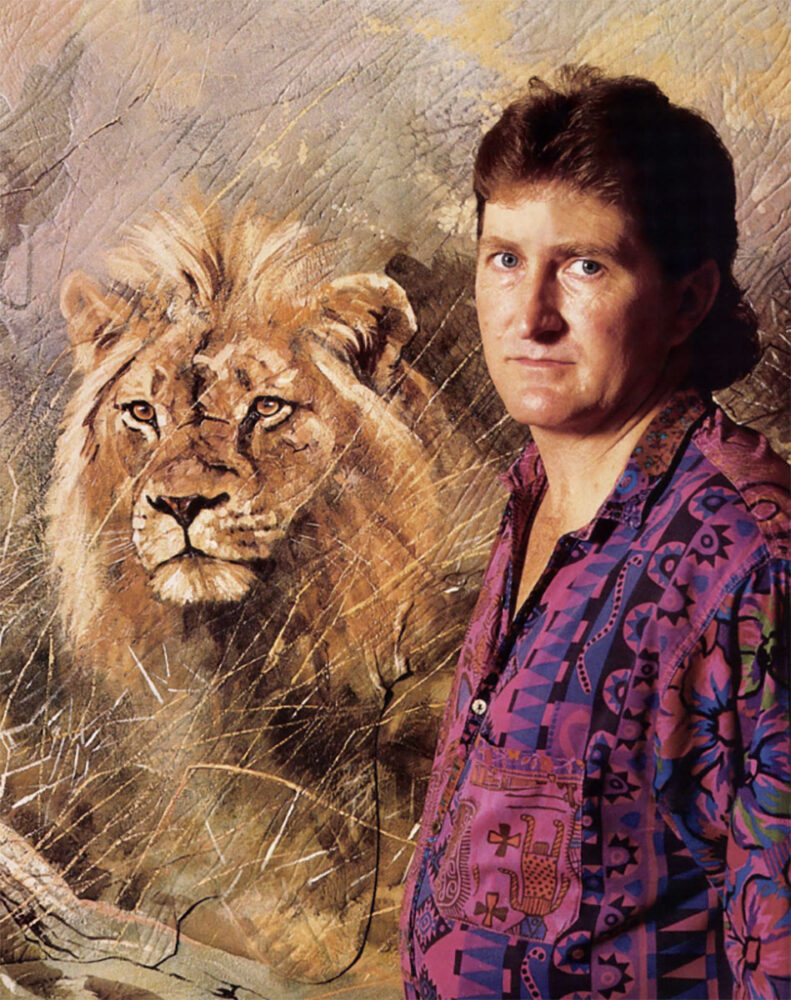

About a year ago, South African artist Kobus Moller arrived at a crossroads in his career. Though demand for his work was high and he was making a comfortable living from his art, Kobus was experiencing the brush-and-canvas equivalent of writer’s block.

Kobus Moller draws from 47 years of observing African wildlife to create stirring portraits such as The Monarch, an oil-an-canvas.

“I thought I was losing it,” he recalls. “I was in the studio every day, painting frantically, but everything I produced looked like trash to me. I had no challenge in painting a kudu to look like a kudu, for example. I knew I could continue to paint animals and that people would buy my work, but I started thinking ‘Is that all there is to it?’ It wasn’t enough for me. I needed a deeper meaning to my art.

‘Then I began to question the essence of art itself. What makes one work great and another not? How can you make a painting have meaning and value for the long term? I felt that unless I could answer some of these questions, I would lose my ability.”

To find some answers, Kobus did two things. “First, I talked to other artists about these questions and philosophies. They assured me that when an artist goes through a process like this, he is about to make a great change. They were right about that.”

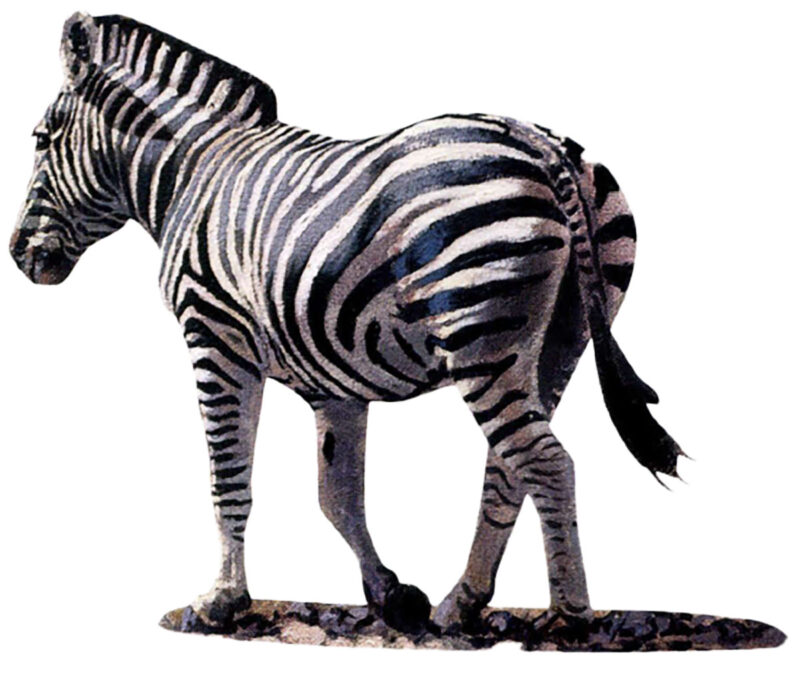

The other step Kobus took was out of the studio. Allowing himself a three-week hiatus from painting, he retreated to a place he knew well: the African bush. He forgot about painting nature and spent days simply observing it. ‘The greatest works of art are out there,” Kobus says fondly. “I flew over the Sahara Desert and was amazed at what I saw. If I blocked out the horizon and focused on the desert itself, the textures and patterns were fantastic. And when I walked a dry riverbed, I could see the same patterns I saw from the plane. Whether you’re at 30,000 feet or two feet, those patterns repeat themselves. Capturing that amazing beauty became the essence of art to me and I was determined to depict it in my work. When I came back to the studio I began painting with renewed confidence.”

This zebra is from his painting, Solo.

The simple interpretation of this tale is that Kobus Moller, like we all do from time-to-time, was just working too hard and needed a break. But probing deeper, we would find two crucial elements of his personality. First, he is not one to wear complacency like an old, comfortable coat; he is continually challenging and questioning his own beliefs and abilities. Second, Kobus is not one who paints Nature because it’s an intriguing and popular subject matter; he relies on it for personal and spiritual sustenance.

Those patterns have repeated themselves in Kobus’ life before. It was only a handful of years ago that he ditched what many South Africans consider a dream job as a college instructor. A lecturer in The College of Education for Further Training, Kobus was teaching, and developing multi-media presentations. He was paid well and his future seemed rosy. But Kobus, who’d drawn and painted all his life, was haunted by an artist’s dreams and ambitions.

“I started looking five or 10 years into my future and I didn’t like what I saw. I enjoyed my job, but my ambition drove me. Climbing the ladder would eventually see me in an office wearing a suit every day. To me, that would have been a nightmare. I was halfway through my Master’s Degree when it hit me — that I wanted to make a living with my art. I discussed it with my family (wife Vita, and children Braam, Marize and Hanri) and with their full support, I decided to resign my post and pursue my art full time.”

Kobus painted The Herd Boss on Cape buffalo hide. For years the artist worked almost exclusively on leather, which he describes as “the most durable medium around, way beyond canvas or board.

Kobus’ career change raised some eyebrows. “In South Africa we are very conservative,” he explains. “Making a decent living and supporting your family is the number one concern, and people value security above all else. When I resigned my job, ripples of indignation ran through my family and friends. But I’ve come to realize that nothing is secure but your faith in God and yourself. Everything else is questionable. Many of my colleagues who criticized me for leaving have now lost their jobs through affirmative action. Making that choice was very good for me.”

And, for the world of wildlife art. When he turned full-time in 1990, Kobus Moller almost immediately established himself as an artist willing to take risks: to depart from the normal and experiment with colors, images, mediums and materials. When I first became aware of his work, Kobus was painting African wildlife on leather — the tanned skins of warthog, Cape buffalo, ostrich and kudu. The new “canvas” created a stunning backdrop for his art and proved his willingness to break new ground.

“I actually got started on leather while I was into pyrography,” Kobus says. “Pyrography, or fire-writing, is the practice of burning images into wood with an instrument like a soldering iron. I was using a lot of different African woods that had grains that were difficult to burn with any kind of consistency. So I began to experiment with leather. Unfortunately, the effects of the iron were lost.

A cheetah and her cubs in Maternal Instincts, a 36 x 30 oil-an-canvas.

“But I was very excited about leather as a medium and I wanted to create the same effects without burning into it. So I tried wood stains. Nothing worked the way I wanted, but all kinds of interesting things happened; colors ran into grooves and created beautiful patterns. I got very excited and went out and bought every type of leather and media I could find and experimented with all of them. I found that acrylic paint used as a base onto chrome-tanned leather was the best combination. I believe leather is also the most durable medium around, way beyond canvas or board.”

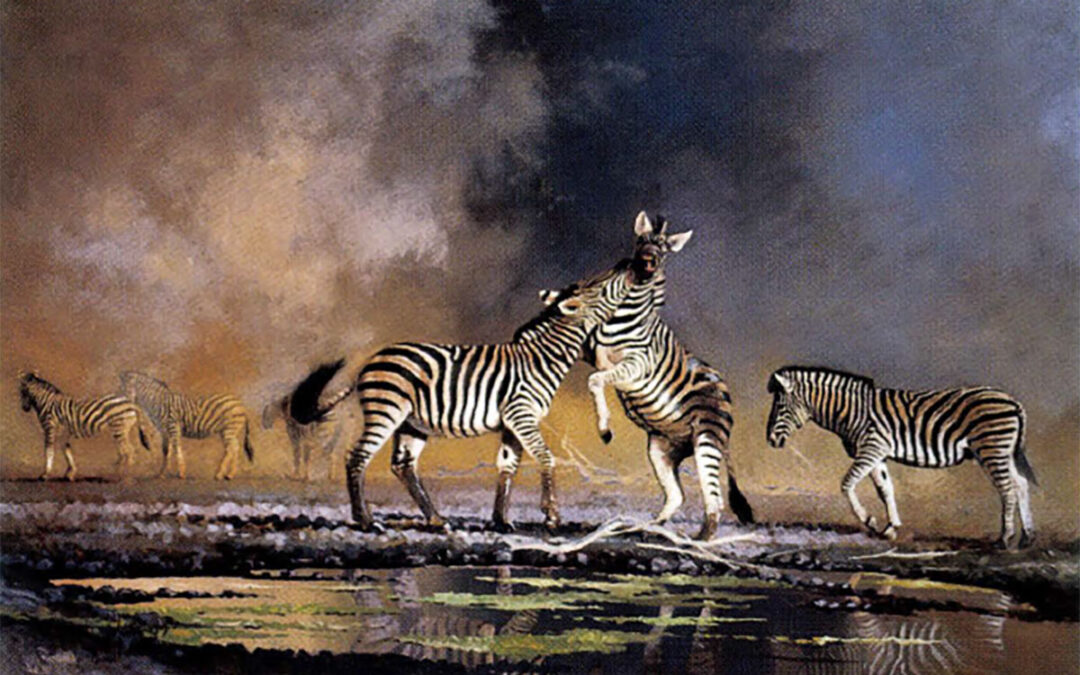

Kobus’ approach to painting is unique as well. Many artists begin with a strong concept; to paint a lion, for example, and plan their painting around this central figure. Kobus takes a more circuitous route. “I start with the medium I have — leather, canvas, whatever — in front of me. I begin by filling my canvas with paint, and this is done — consciously or subconsciously — by using geometric shapes such as triangles. Then I might start transposing circles on top of them, using as many application methods as I can; very wet or very dry, for instance. At some point, something that is happening on the canvas will jolt something in me -like the impression of a lion’s mouth. Then I just start using the effects I’ve already created to complete the rest of the image. Often, the animal looks almost like the landscape and vice versa. And that’s how it is in nature, too.”

Kobus’ paintings reflect an intimate knowledge of the African landscape, a knowledge gained from a life spent exploring it. Born and raised on a farm outside Fort Victoria (now called Masvingo) in Zimbabwe, Kobus was the youngest of four Moller boys. “We grew up in a beautiful area,” he recalls. “There was a river nearby where we fished, canoed and watched birds. There wasn’t a lot of big wildlife in our area, but I was always fascinated by nature.”

Kobus Moller says that painting color and light is a “continual challenge, ” but this portrait of leopard, entitled That Look, represents a magnificent blending of both.

Kobus also learned to draw as a youth, encouraged by his father, a talented landscape and still-life painter. “My interest and abilities came from watching my father working in his studio. I was involved in art since I can remember. The first drawing I ever did – of a horse – got me a lot of attention. The teacher grabbed it away from me and ran out of the room to get the principal. I thought I had done something wrong, but she was just excited about the drawing. So I knew early that this talent was special, that not everyone had it.”

After high school, Kobus continued his education and became a teacher. He also spent time in the military, and fought in the war in Rhodesia that lasted from 1968-79. Some of his field experiences put him in close contact with African wildlife that was as threatening as any enemy activity.

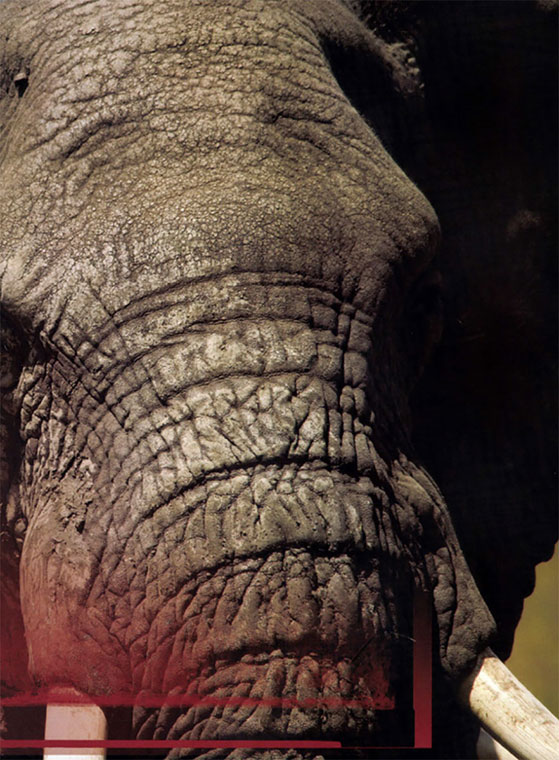

“We had a lot of very exciting, sometimes scary experiences while I was patrolling the Zambezi Valley,” Kobus recalls. “We were in close contact with elephants, buffalo, lions and rhinos – they were very scary and would charge off in every direction. At night, we’d just lay down on a ground cloth, often near a game track. It’s something to be awakened by a lion’s roar at close range without even a tent to protect you. But it was a wonderful, fantastic experience that led directly to what I’m doing now. ”

After his Rhodesia experience, Kobus did another stint in the army. Though his duties were decidedly less field-oriented, they also had a telling effect on his career as an artist. “I was assigned to a unit that was involved in media production for training purposes, which included television, slides and audio. I might present a show using several slide projectors flashing images on a screen in quick succession. That experience taught me how quickly the human eye is capable of processing images. Human observation is so good that you can drive down an unfamiliar road and, years later, look at a picture of that place and recognize it instantly. Learning this led to my current style of painting, which is a form of multi-images — not a [painted] reproduction of a photographic image.”

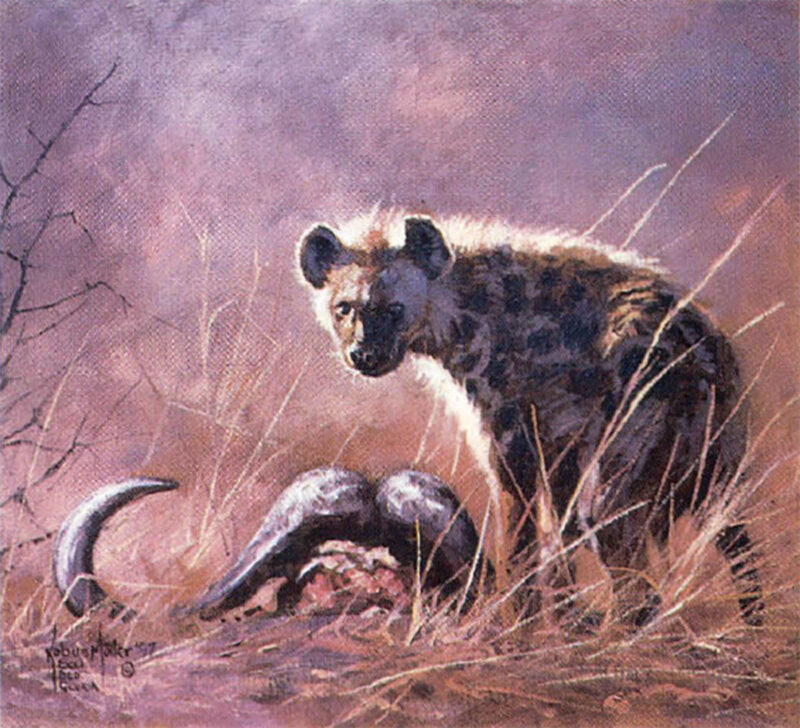

In Grim Reminder, the artist relates the age-old story of life-and-death on the African plains.

Such an art philosophy seems too technical to grasp, but then Kobus simplified it for me. “Let’s say I’m walking through the bush, not seeing any wildlife. Suddenly, I just feel there’s a buffalo there. Maybe I saw a form, a portion of an ear or a bit of horn, but without consciously registering it. My subconscious then manages to warn me of buffalo. That’s how I believe the subconscious works, and what I try to capture when I paint.”

Kobus’ commitment to painting wildlife as part of the landscape is a steppingstone to his other goal: capturing the essence of each animal. “I need not only to paint the buffalo correctly, but also what it is that makes a buffalo a buffalo. That includes the bush around him, other animals nearby… All these things have been going on for a very long time, and you need to study and observe them very closely in order to understand the relationships.”

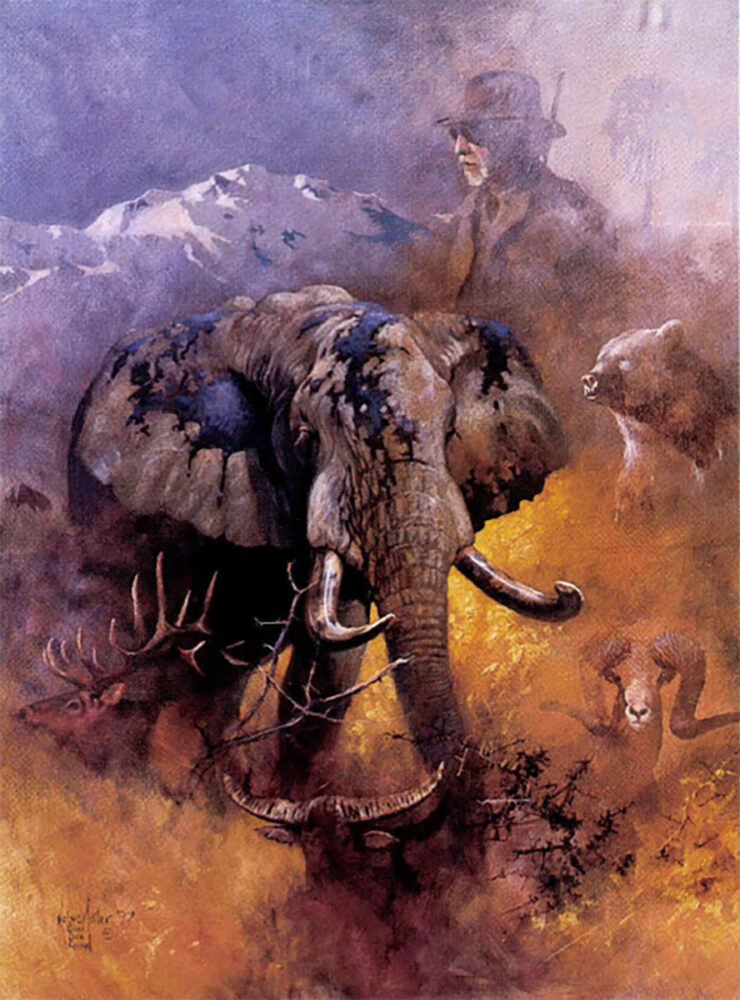

The Quest was commissioned by the Dallas Safari Club for its fund-raising event. After the painting is auctioned, Kobus will replace the image of his friend Randy Garrett with that of the new owner.

In 1991 Kobus brought his art to America and was immediately impressed by what he saw. “My first Safari Club International show was a real eye opener,” he says. “There was a very positive reaction to my work, but I realized that the standards here were very high.” At that SCI exhibit, Kobus met Paul Jenkins, who was so impressed with Moller’s art that the two formed a partnership. Kobus continues to live and work in South Africa (there is talk of a move to the U.S., but he still has many ties to his homeland), while Jenkins represents his art internationally. The two maintain close contact, and Kobus’ reputation is growing.

But don’t expect the 47-year-old artist to rest on his proverbial laurels. While he admits to being pleased with much of his progress, he is constantly driven to improve. “Color and light present a continual challenge for me,” he notes. “Light affects color in so many ways, and it’s a struggle to learn their properties. I’m experimenting now with new approaches I hope will help me master them.

“Most of the artists I know will go out in the bush, take thousands of photos, then go back to the studio and design a composition incorporating all the research they’ve just completed,” he says. “To me, the most important time in the bush is just spent observing. I do take a camera, and I do take photos, but I really try to watch what is happening around me and translate that into my work. To me, you should judge the painting by the emotion it creates. Can you translate the excitement and the fear you felt when the elephant charged through the trees? Can you impart the wonder of watching a big leopard glide through the bush? These are the biggest challenges of all.”

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now