No one was fully aware of the buffalo’s impending demise, not even the countless hidemen who rushed out West to hunt the huge beasts.

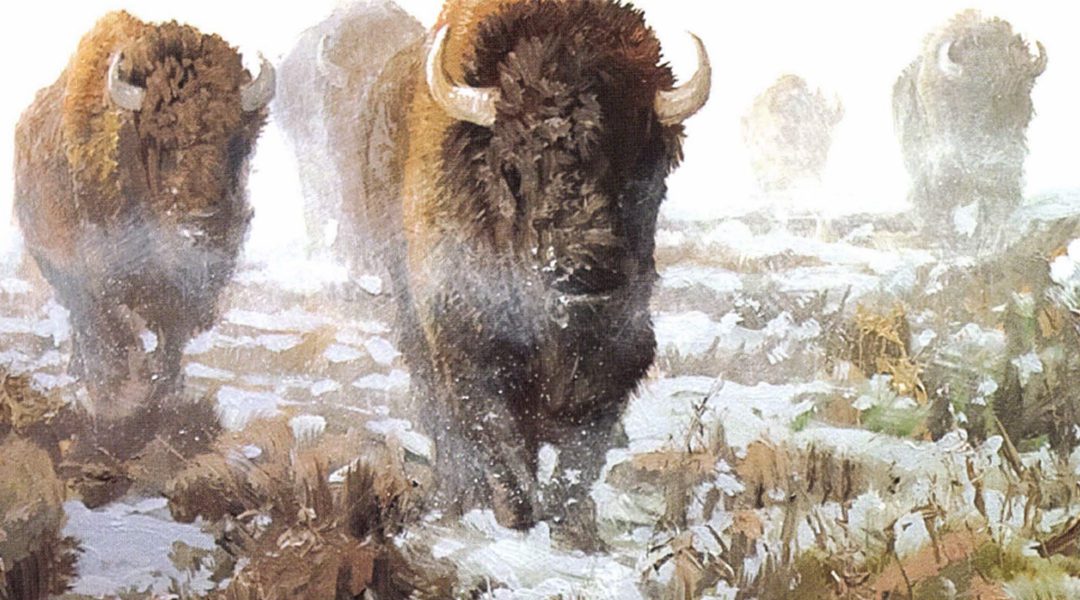

John and George rode silently across the snow-covered plain, staying to the windward side of the big herd. The buffalo were slowly moving toward a gully where the two men, sharp rifles in hand, decided to wait downwind of oncoming animals. Their plan was to pick off the buffalo one at a time as they emerged from the gully.

This was a new hunting technique called “getting a stand.” The lead bull would be shot first and hopefully drop where it stood. The other buffalo would come to examine their fallen comrade, unaware of danger. Then the hunters would pick off others as they milled around. The buffalo would become confused and the hunters could kill as many of them as they wished, without moving from their position.

Meat was the main prize of buffalo hunters before 1871, but then the hides took on a value of the Great Buffalo Hunt, when hide dealers in the eastern U.S. and in Europe were dictating the market.

John and George were just part of the faceless and nameless thousands who saw the money to be made and rushed out West to hunt buffalo. One man could kill up to 100 animals from one location in less than an hour.

The commercial slaughter of the buffalo herds continued through the 1870s. Hide dealers such as J.N. Dubois of Kansas City and William C. Lebenstein of Ft. Leavenworth led the charge and controlled the market. Tannery operations in Manchester, England, and elsewhere in Europe had devised techniques to make the hides serviceable for clothing, high-end furniture and the carriage industry. Buffalo hunters were getting from $1.50 to $3 per hide.

As the years progressed the hidemen became more organized and mobile camps were set up on the plains to process the meat and hides. These crude camps proved to be very productive. Their crews erected scaffolding where meat and tongues would be hung to dry while the hides were being cleaned and pegged out to dry before hauling to market in ox-drawn wagons.

The camps were complete with chuckwagons, tents, firearms and even a mobile grindstone to keep all the skinning knives sharpened.

By 1876 professional hide hunters had become more brazen and cavalier about killing buffalo and were out shooting the amateurs who had flocked to the plains to make their fortune.

Texas hideman John R. Cook walked to within 80 yards of a resting herd. Setting up his rest sticks, he placed his heavy Sharps in the crotch, then took aim and fired at the nearest bull. But the animals didn’t act as they normally would. At the sound of the shot, about half the herd stood and looked at him menacingly, then turned and moved off toward a creek. Cook knew he still had a possible stand and continued firing and reloading, firing and reloading.

Texas hideman John R. Cook walked to within 80 yards of a resting herd. Setting up his rest sticks, he placed his heavy Sharps in the crotch, then took aim and fired at the nearest bull. But the animals didn’t act as they normally would. At the sound of the shot, about half the herd stood and looked at him menacingly, then turned and moved off toward a creek. Cook knew he still had a possible stand and continued firing and reloading, firing and reloading.

When the smoke eventually cleared, he had taken down 25 of the wooly beasts. His companion Charlie came up behind him and gave him another rifle and some more ammunition.

Cook continued firing as the buffalo milled about, confused by the smell of death around them. Meanwhile Charlie was cooling the other gun by pouring water down the muzzle and letting it run out by pulling down the breechblock. The gun was then left to cool off, while Cook shot more buffalo.

After an hour or more and a couple of gun changes, 88 buffalo lay dead in front of him. This was by no means the largest buffalo stand ever recorded. That same year, J. Wright Mooar, who was considered to be the dean of buffalo hunters, shot a stand of 96 buffalo and went on to harvest an incredible 20,500 bison over a period of nine years. The famous peace officer, Bill Tilghman, claimed to have brought down 3,300 buffalo in one year. James H. Cator, a transplanted Englishman, is said to have averaged 4,000 buffalo hides per year over three years.

With the plains boasting an estimated 20 million buffalo, it became obvious to anyone handy with a rifle that there was a lot of money to be made out West. Cator, for instance, probably grossed $12,000 per year from his killings. Taking into account the cost of cartridges at that time (25 cents per), he probably netted $11,000 a year.

But for many would-be hidemen, the hunts were not as easy. For instance, more than one bullet was often needed to bring down a buffalo bull. The arduous living conditions and the constant threat from Native American Indians forced many of the buffalo outfits to close down after only one season. Some hardly broke even.

Before the 1870s came to an end, huge buffalo processing plants had been set up near railroad stations strung across the western and southern plains. The raw hides were pegged, dried, pressed and baled, ready for transporting back East. The animals’ bones, meanwhile, were separated out and shipped to fertilizer manufacturers.

With the southern and western plains virtually depleted of the wooly giants, the buffalo hunters followed the remaining herds up to the northern plains. It was there during the next three years the buffalo would be driven to the brink of extinction.

Renowned hunter William T. Hornaday observed that no one was fully aware of the buffalo’s demise, not even the lude hunters themselves. Little did they know that when they returned at the end of the 1882/1883 season, it would be the end of buffalo hunting as a way of making a living. In the fall of 1883, oblivious to the plight of their quarry, the hidemen went to the expense of outfitting themselves in the usual way and headed out to the known buffalo ranges, but this time they returned empty-handed, broke and bankrupt. In just 11 years the buffalo millions were gone.

This spectacular sequel to John Seerey-Lester’s immensely popular Legends of the Hunt will feature over 120 paintings and some 60 stories covering the remarkable true-life adventures of many of the world’s greatest hunters/explorers. Foreword by Tweed Roosevelt. Buy Now

This spectacular sequel to John Seerey-Lester’s immensely popular Legends of the Hunt will feature over 120 paintings and some 60 stories covering the remarkable true-life adventures of many of the world’s greatest hunters/explorers. Foreword by Tweed Roosevelt. Buy Now