Newfoundland and Labrador’s crystal-clear waters teem with brook trout, a telling testament to this unspoiled land.

Nowhere on the planet is trout used as a verb except in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada’s most easterly and youngest province. In all the dictionaries, trout is presented as a noun, as a type of fish. But here in my home province, we say we are going trouting, and that means specifically that we are angling with a rod for brook trout. For any other species of fish, angling with a rod is simply fishing, the same as anywhere else in the English–speaking world. I believe that this quirk of language speaks to how deeply brook trout are rooted in Newfoundland’s everyday life and culture.

I won’t try to convince you why the speckled or brook trout is held in high esteem. It is a common sentiment in many places. A quick Internet search will quickly illustrate that in the world of casting creations of fur and feather with sticks of graphite or cane, the brook trout is considered a mighty fine quarry—regardless of size.

For those of you not familiar with the geography of Eastern Canada, Labrador is a section of the Canadian mainland and Newfoundland is an island. Together with Labrador, a vast land of 113,640 square miles, Newfoundland makes up the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Confused yet?

Have a look at a map. Labrador is huge (Newfies call it the Big Land), nearly equal to the land area of Jolly Old England and New England combined. Now here’s the really exciting part. Labrador has 12,100 square miles of fresh water and a grand total human population of less than 30,000. There are many lakes in Labrador that are filled with huge brook trout but have never been fished by a fly angler. For brook trout anglers, this is the Promised Land, the Holy Grail for squaretails.

The island of Newfoundland is smaller than Labrador, 42,030 square miles, still almost the area of England, and with myriad trout water, big and small. There are no pike, lake trout, or any predators of brook trout, other than birds of prey. So the brookies abound in astronomical numbers, maybe not the massive trophies you’ll catch in Labrador, but the water is much more accessible and very prolific. Four-pound trout are a realistic expectation if you fish smart, and 10- to 14-inch brookies are everywhere.

In each part of the province, the habitat is pristine. Brook trout don’t tolerate soiled or dirty water like many of their cousins. They just don’t integrate well into urban planning schemes. They are a fish of wild places and cold, crystal-clear waters. If brook trout are present, then the ecosystem is healthy and happy—a canary of sorts.

Newfoundland and Labrador teems with brookies, every nook and cranny, a telling testament to an unspoiled land—and nowhere is the fishing any better than Igloo Lake.

In 1968 I had reached the tender age of 9 and my father had a notion for him and me to try Atlantic salmon angling, but in Newfoundland, salmon may be taken by fly only. Dad had done a tiny bit of fly casting for trout, but I had only drowned worms with my bamboo pole and hurled a few spinners with a very troublesome reel. Dad’s fly casting had been with an old bamboo rod that he had broken in a car door a few years earlier. We both had much to learn.

When I came home from the last day of grade four with a very good report card, Dad handed me a brand new fly fishing outfit. The Algonquin fiberglass rod is long gone, but I still have the J.W. Young fly reel, which worked a heck of a lot better than the closed-face spinning reel I’d been using. Dad had a new fly fishing outfit as well, and we were ready to learn.

At the time we lived in St. Anthony, a regional service town at the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula in a very remote part of the island. The fishing for salmon and trout was amazing. I was a very lucky boy.

We first went salmon fishing at Big Brook, where in spite of sloppy casting, both Dad and I each caught our first salmon. Actually, on one day we caught seven Atlantics between us. What we lacked in skill, the river compensated with abundant fish, and minimal angling pressure.

Salmon season is short and Dad and I were once again trouting. Why not put those new fly rods to good use? We started fly fishing for brookies and ceased digging up worms.

On a business trip to St. John’s Dad bought about a hundred trout flies, which were in short supply in St. Anthony at the time. We grew more proficient at the casting game and learned how to properly present flies. An English doctor at the hospital gave us some lessons and taught us the art of the dry fly. With no proper fly-dressing in town, we improvised with hairstyling cream. Those were wonderful times as Dad and I discovered the art of the long rod together.

The good doctor also warned Dad that addiction was a real possibility, but he told us too late. Obsession developed quickly, and as years passed I craved bigger trout and other species and other places. The die had been cast, and I knew I’d spend whatever spare time my life and resources permitted to fly fish. I took a fork in the road that has lead to casting flies to a wide variety of gamefish species all over the world—and, in particular, a quest for an eight-pound brookie in my home province.

In the summer of 2014 I went to Igloo Lake to find my eight-pound brookie. I booked a trip with my friend, Jim Burton, who owns and operates Igloo Lake Lodge, which is on the lake in the headwaters of the majestic Eagle River.

I stood in a 20-foot wooden canoe (we call them Gander River Boats) with a 15-horsepower outboard on the stern. Hardly a breath of wind on Igloo Lake, and I wished Dad could have been with me to see the mayflies hatching all around and the giant brookies, conserving energy by moving in a straight line, slurping them down.

We targeted individual feeding fish—trouting at its finest. We had spotted a very large brookie, and I hoped to drop the correct fly with finesse, accuracy, and stealth in its path. A lot can go wrong, particularly with the breadth and depth of the cast. And notice I said correct fly—there’s always that matching-the-hatch issue to contend with. But my cast needed to fall in the fish’s feeding lane and the correct span in front of it. I gauged the distances between its slurps and began my presentation. The cast took skill, but I didn’t panic. Even if I missed, opportunities abound on Igloo Lake during a mayfly hatch.

But I didn’t miss. I cast about 50 feet directly into the path of the trout and about two slurps ahead of it. With one living mayfly gone, my presentation sat next in line, and when it disappeared, the line smacked bar tight. The Loop 10-foot rod that I bought specifically for this trip strained down to the cork. This was it. Like King Arthur, I had discovered the Holy Grail.

But I didn’t miss. I cast about 50 feet directly into the path of the trout and about two slurps ahead of it. With one living mayfly gone, my presentation sat next in line, and when it disappeared, the line smacked bar tight. The Loop 10-foot rod that I bought specifically for this trip strained down to the cork. This was it. Like King Arthur, I had discovered the Holy Grail.

By the weight and strength pulling the line, I felt my quest for an eight-pound brookie might be soon realized. The trout fought hard, but its sinew and muscle eventually tired. After four or five minutes of fight against a strong but deeply bowed stick, the fish’s strength waned.

I lead the prize toward my skilled guide, who used a knotless net—every precaution is taken at Igloo Lake to avoid any harm to these rare and wonderful fish. With only short time weighing and measuring and a quick photo, I felt on top of the world. The giant brookie weight 8 pounds 4 ounces—a fish of a lifetime.

Photos: Paul Smith

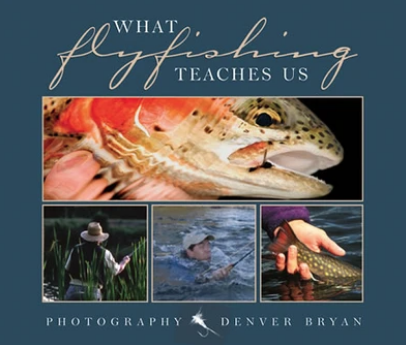

Fly fishing is a noble sport whose avid practitioners learn the skills of finesse, observation and technique-and that would be great if it all stopped there. But fly fishing is more-oh so much more-than the stream side perfection of a mere handful of angling skills. What Fly Fishing Teaches Us relates these lessons and many more in pithy words from angling literature and dazzling Denver Bryan photographs. Fly anglers who have found utter enjoyment and headache-inducing frustration will recognize themselves in this delightful book. Buy Now

Fly fishing is a noble sport whose avid practitioners learn the skills of finesse, observation and technique-and that would be great if it all stopped there. But fly fishing is more-oh so much more-than the stream side perfection of a mere handful of angling skills. What Fly Fishing Teaches Us relates these lessons and many more in pithy words from angling literature and dazzling Denver Bryan photographs. Fly anglers who have found utter enjoyment and headache-inducing frustration will recognize themselves in this delightful book. Buy Now