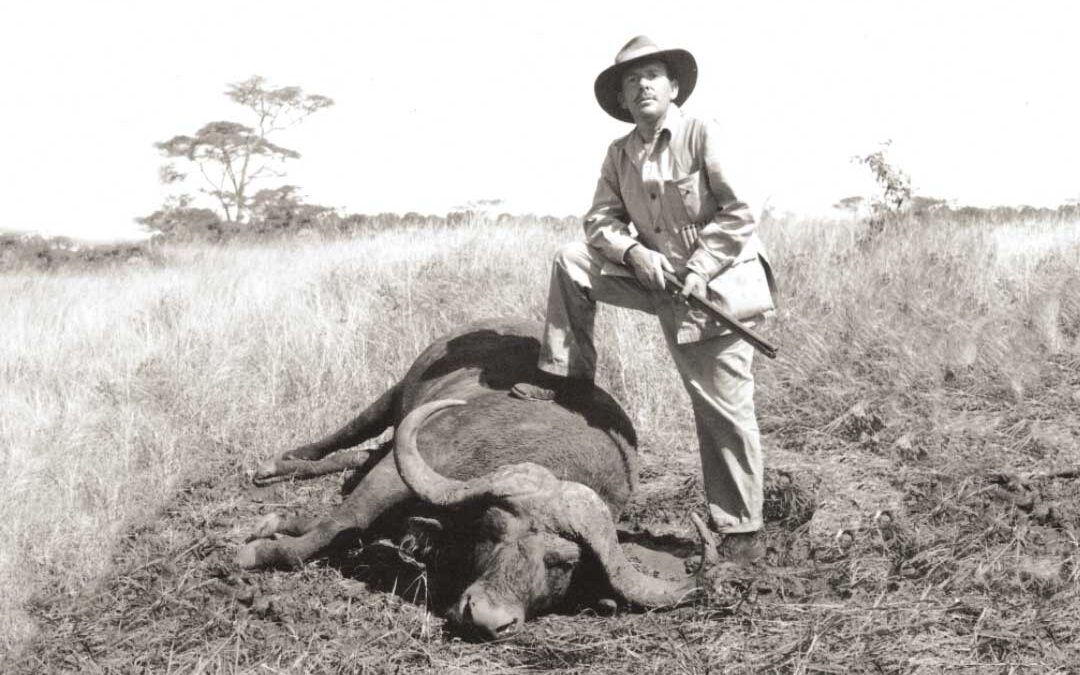

Anyone with so much as a passing acquaintance with sporting literature is familiar with Robert Chester Ruark. He is probably the best-loved and most widely read outdoor writer of this century.

Certainly, Ruark’s timeless and immensely popular books The Old Man and the Boy (1957) and The Old Man’s Boy Grows Older (1961) should be read and re-read by anyone who cherishes the outdoors. In these books, comprised of tales from Field & Stream, Ruark’s grandfather dispenses wit and wisdom, liberally sprinkled with doses of practical philosophy on the natural world and life in general. Nowhere have youthful rites of sporting passage and the camaraderie that’s a part of the outdoorsman’s milieu been depicted in more telling fashion.

Yet for all that I treasure these books, they are not Ruark at his best. That distinction must be reserved for Horn of the Hunter (1953).

Ruark often styled himself as “the poor man’s Hemingway,” but to my way of thinking, Horn of the Hunter, a product of the author’s early and supremely impressionable contact with Africa, outshines Papa’s The Green Hills of Africa. It is also the most desirable of Ruark’s books.

Of course, any serious fan of Ruark’s cannot overlook his novels. The early ones, Grenadine Etching (1947), I Didn’t Know It Was Loaded (1948), One for the Road (1949) and Grenadine’s Spawn (1952) are satirical works whose rapier thrusts of wit and spoof cut clearly enough when published, though they have been dulled by the passage of time. The same cannot be said of the blockbuster novels that made Ruark’s name a household word and earned him a fortune (as well as putting him on the fast track to alcoholic self-destruction). Three of these, Something of Value (1955), Uhuru (1962) and The Honey Badger (1965), grew out of his experiences in Africa.

Ruark’s fourth major novel, Poor No More (1959), carries significant autobiographical overtones. His other two books, both published posthumously, were anthologies of magazine articles and related work. These were Use Enough Gun (1966) and Women (1967).

Since Ruark’s death in 1965, just shy of his 50th birthday, surprisingly little of real substance had been written about him, until Michael McIntosh brought together a collection of Ruark’s African pieces, replete with an insightful introduction, in Robert Ruark’s Africa (1991). Now, belatedly, we have the first full-length evaluation of Ruark in Huge W. Foster’s Someone of Value: A Biography of Robert Ruark.

Produced by Trophy Room Books in a signed, numbered edition of 1,000, this is a book that both excites and exasperates. In some ways it is very good; in others most disappointing. Let’s look at some of the work’s considerable merits first.

Foster has obvious familiarity with Africa, and the fact that a lot of research underlies the writing of this book is equally manifest. His list of sources shows a lot of ferreting in the form of interviews along with extensive correspondence. Likewise, the author seems to have done yeoman duty in that portion of Ruark’s personal papers in the library at the University of North Carolina. Esthetically, the book is nicely produced with some good photographs.

Set against these pluses are all sorts of curious oversights. For one thing, Ruark the sportsman receives short shrift. I would argue that it is his work as a sporting scribe that is his greatest gift of posterity. Some of this neglect of sporting matters, especially in Ruark’s formative years, may well come from a misguided sense of political correctness on the part of Foster. A good deal of what he says in his Epilogue, “The Africa That Was,” is sheer claptrap (I say that not just as an outdoor writer, but as someone who teaches college-level courses on Africa’s past with several academic books on the continent behind me).

No matter how much familiarity Foster has with Africa, to state that Kenya is “an oasis of success in a desert of failure” is to be guilty, and this is putting it charitably, of the worst kind of myopia. Likewise, he is about as wide of the mark as is possible when he suggests that “the Kenya of the present, while not without its problems, is the Kenya that to a large extent Bob hoped for.”

Quite simply, Ruark would have been appalled at developments in East Africa as well as elsewhere. To believe, as Foster seems to, that this quintessential hunter would have approved of the ban on big game hunting should vex any true sportsman.

To be truly meaningful, a biography needs to be an ongoing exercise in analysis. Foster does offer some interpretation at the end, albeit more by way of a commentary on the state of contemporary African affairs than on Ruark the man. Elsewhere, however, there is far too much of what is sometimes described as scissors-and-paste writing. We are given endless quotations, mostly from Ruark’s newspaper columns (the least enduring of all the corpus of his writing), tenuously linked by a few sentences from Foster. My reservations about the Epilogue notwithstanding, I would have liked to see more of what Foster thought about his subject.

Then there is the research – deep yet curiously narrow. Nowhere is McIntosh’s book mentioned, and a dozen vital treatments of Ruark in periodicals are overlooked.

Yet concerns such as these pale in comparison with the interview aspect of Foster’s research. One could compile an impressive list of those who are conspicuous by their absence. Where is Harry Selby, Ruark’s close friend and beloved white hunter? Where, too, is the recently deceased Harold Matson, his long-time and long-suffering literary agent? Many of the friends Ruark made in Africa were not interviewed.

Despite its shortcomings, the book will be helpful to future students and biographers of Ruark. Its contents serve to convince us that he was, as the title suggests, “Someone of Value.” In short, while far from being a definitive biography, this is a volume that nonetheless belongs in any collection of Ruark books.

In addition to being covered in dozens of articles over the past two decades, Ruark has been the focal point of two books, both of which I edited. The first was The Lost Classics of Robert Ruark (1996), which included 27 hunting adventures that had never been published in book form.

Considerably more significant was Ruark Remembered, published by Sporting Classics in 2006.

A trio of staunch Ruark fans from the Southport, North Carolina, area made a pilgrimage to Palomas, Spain, where the celebrated author lived in his later years. There, they discovered that Alan Ritchie, who served as Ruark’s secretary for 12 years, had written a full biography of his employer immediately following Ruark’s death in 1965. They purchased the manuscript from a friend of Ritchie’s, then asked me to edit the text and Sporting Classics to publish it.

Turning a 768-page typescript, much of it loosely organized and lacking smooth transitions, into a finished book was quite an undertaking. For me, however, it was a labor of love, and the finished product shed a great deal of new insight on the man and his milieu. The 350-page book also features many rare photographs.

Ritchie treated his friend and employer fairly and frankly, but the man who emerges from the pages of Ruark Remembered is not always likeable and almost never a sympathetic character. Yet anyone who enjoys Ruark’s writing (and who doesn’t) will find Ritchie’s biography a compelling read.