What you will get is an American original: Ray Wilson Scott, Jr. of Pintlala, Alabama, founder and president of Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (B.A.S.S.), a man known to hundreds of thousands of folks as Mr. Bass.

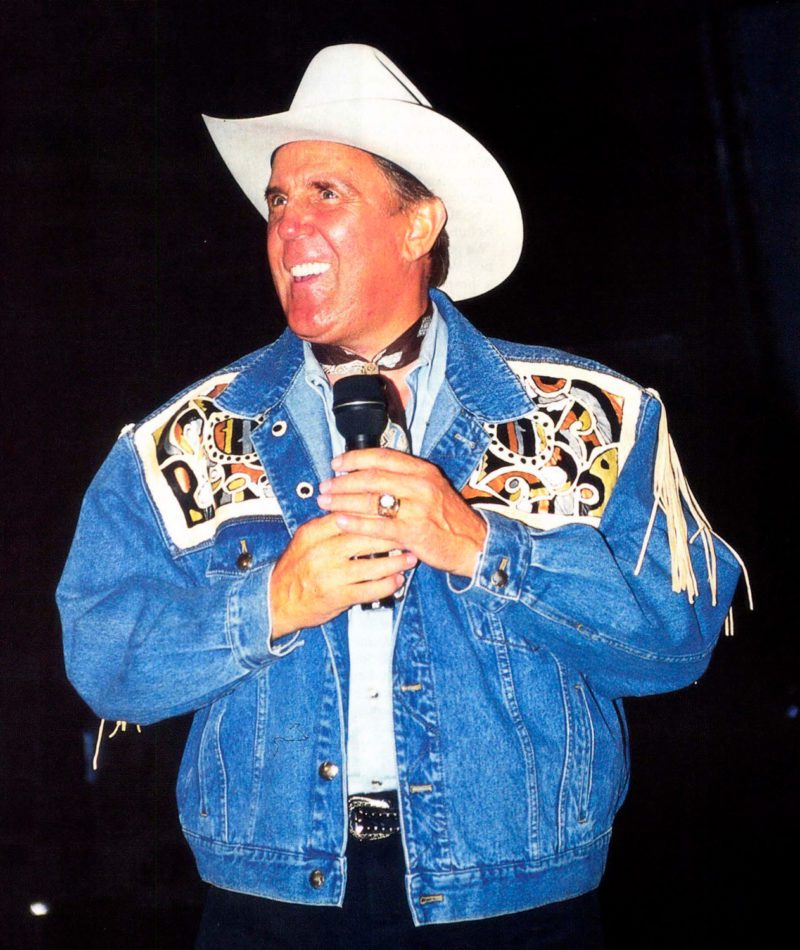

Like an old testament prophet incongruously attired in white stetson and fringed jacket, Ray Scott can work a gathering of bass fisherman into a cheering frenzy. Photo by Gerald Crawford.

Begun in 1968, B.A.S.S. has grown to more than a half-million members in fifty states and fifty-two countries. Now you may think such a large organization would be the creation of a committee of executives and consultants working over a long period of time. Not true. B.A.S.S. begins with the story of a thirty- three-year-old man in his underwear in a motel room of a Ramada Inn in Jackson, Mississippi.

He has just returned from an uneventful day of cold, soggy fishing and is wet to the bone. Undressing, he showers, puts on clean underwear, and flops on the bed. It’s Saturday, and he is mindlessly watching some sporting event on the television.

It was then the epiphany came, like that of Saul struck from his horse on the road to Damascus: “I had this vision – it just popped in my head – of a fishing tournament. I saw a hundred men, the best bass fishermen in the world, competing nose to nose, rod to rod, for three days. I saw a $100 entry fee, a $5,000 prize, and $5,000 for promotion. It all happened in a computer flash.

I even saw the lake in northwest Arkansas, Beaver Lake. I was conscious, wide-awake – and boom, like the pop of a finger.”

B.A.S.S. began that afternoon in Jackson, with Ray Scott jumping up and down on the bed in his “gotchas,” his head full of this vision, and yelling “I got it! I got it!” to the empty room. He describes that day and many serendipitous events that happened subsequently as a kind of “divine intervention.” Whatever role deity may have played in the founding of the B.A.S.S. empire, the good ol’ boy equivalent of Chutzpah was equally important.

Scott did not wait long to act upon his revelation. By Monday, he was in Little Rock at the state capitol building looking for the office of tourism. He walked into the office and introduced himself as “Ray Scott with the All American Bass Tournament.” The words just poured, unrehearsed, from his mouth. “We are planning a tournament in Beaver Lake in the northwest comer. Which towns should I call on to be our host city?”

He was directed to two towns: Springdale and Rogers. After a quick turndown from the Rogers Chamber of Commerce, he got Lee Zachery on the phone at the Springdale Chamber of Commerce. He recalls the conversation went something like this:

“Mr. Zachery, I’m with the All American Bass Fishing Tournament. Would you be interested in sponsoring our tournament in Springdale?”

“Yes sir, Mr. Scott,” Zachery replied. “I’ve heard of your fine organization. We’d love to sponsor your tournament. When can we talk?” Lee Zachery showed a certain clairvoyance, since the tournament and organization were only seventy-two-hours old and nothing more than an idea burning in Ray Scott’s mind.

That conversation led to a meeting over coffee at the Holiday Inn in Springdale with Zachery and Joe Robinson. After Scott recounted his plans for the tournament, Robinson narrowed his eyes to an inquisitive squint and asked, “Mr. Scott, can I ask you something? How many of these bass fishin’ tournaments have you put on?”

Scott didn’t flinch. “Matter of fact, this will be my first one.”

“And what, Mr. Scott, makes you think you can do this?” he further inquired.

“I just know I can,” Scott replied.

Even with the support of Zachery and Robinson, the Chamber of Commerce refused to endorse Scott and the tournament by giving him the $5,000 he had asked for. Undoubtedly they had visions of Scott absconding with the five G’s, and likely their clothes as well, and they’d have to face an incredulous, mocking electorate wearing nothing but old rain barrels. Their one concession was that he could use a small office in the back of the chamber meeting room, but he could not use their name in any way.

Then the first of many happy coincidences occurred, without Scott asking for anything. He and Robinson retreated to the latter’s real estate office to discuss options. The door opened, and in walked an angel in the person of Dr. Stanley Applegate, a member of the Chamber who had been unable to attend the meeting. Scott presented Dr. Applegate with the same conviction and confidence he had everyone else, stating “I can make this happen, but it would help if the chamber would support it.”

At that point, Dr. Applegate reached into his pocket, pulled out his checkbook and scribbled something on it. He handed it to Scott. It was a check for $3,500. His only words, as Scott recalls, were, “If it works, you can pay me back. If it doesn’t work, all I ask is that you never tell my wife about this.”

With that he turned and walked out the door.

Scott winked at Robinson and said “We got us a show, boy. We got us a show.”

The next few weeks were filled with hectic planning. True, he had seed money, but he had no show – no anglers, no help, no phones – nothing. Working twenty-four-hour days, he hired an assistant, one Darlene Phillips, informing her that though he had a job, he couldn’t afford to pay her right away. He got a WATS line installed, rented an electric typewriter, printed up letterhead stationery and worked the phones relentlessly. Four names grew into dozens, dozens into hundreds.

He worked the phone from east to west as the sun rose across the continent. He wanted the best bass fishermen in America, but also “men of good character.”

Also during this time, as the list of names grew, he locked himself in a room for three days and wrote the tournament rules on a legal pad, then started pounding out letters to prospective participants, telling them they had been recommended to participate in this great tournament and asking them to call him collect. To save money, he worked out a scheme with Darlene. When the collect calls came in, Darlene would inform the caller that Mr. Scott was in a meeting, and he would return their call as soon as possible. Then he would call them back on the cheaper WATS line, while giving the image that he was a well-financed operation that could accept collect long distance calls.

Now at this point, it is easy to start thinking that maybe Mr. Scott is, more than anything else, a con man. Certainly, the Springdale Chamber of Commerce worried that might be the case. Scott forcefully denies being a con man, asserting that he is a promoter. The distinction is crucial, Scott says: “A con man, he can put it on you once, then he’s got to find someone else. A promoter can put it on you, and you’ll want to come back again and again.”

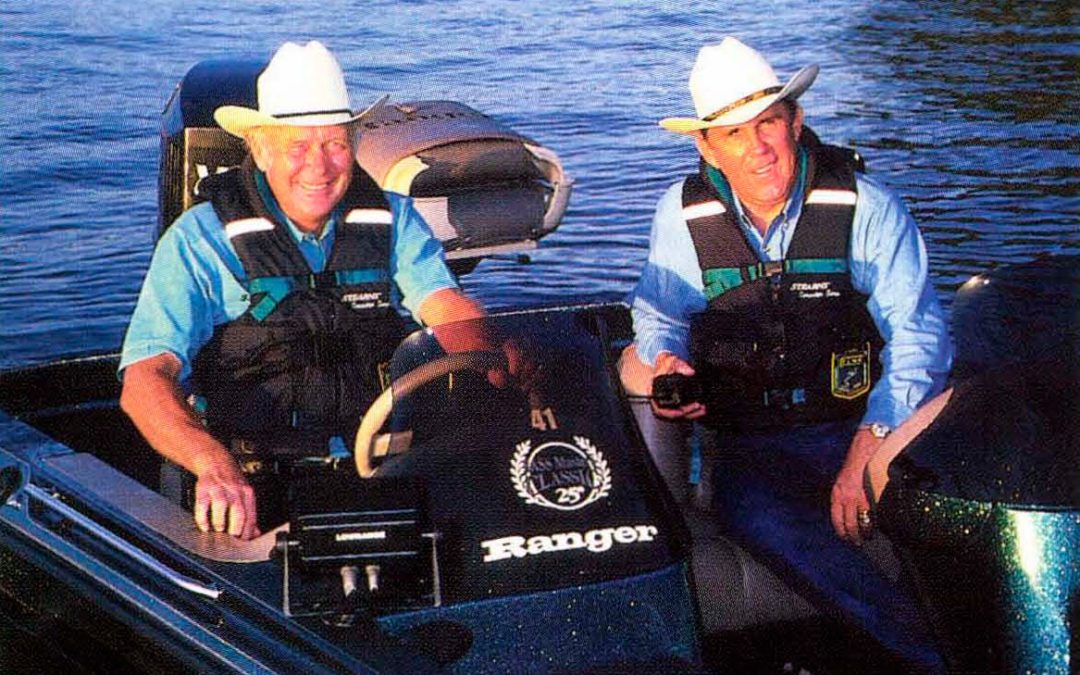

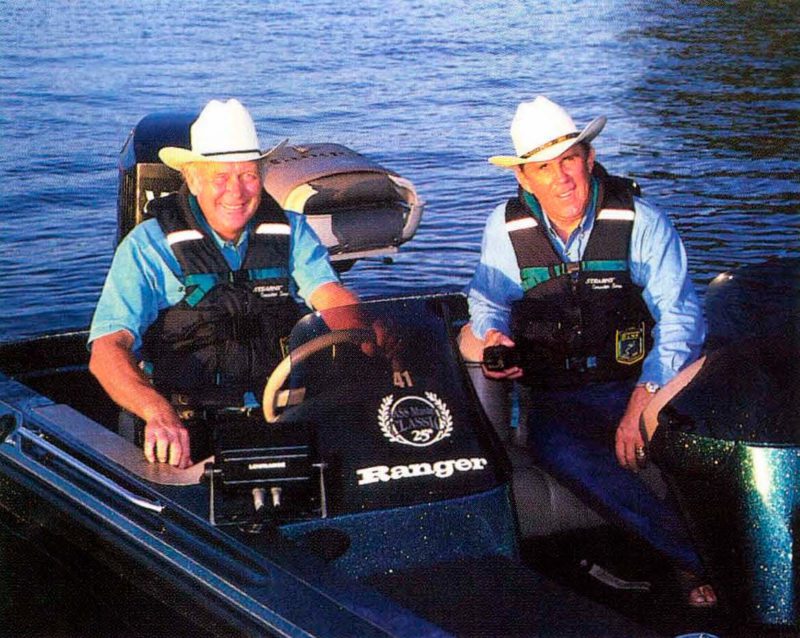

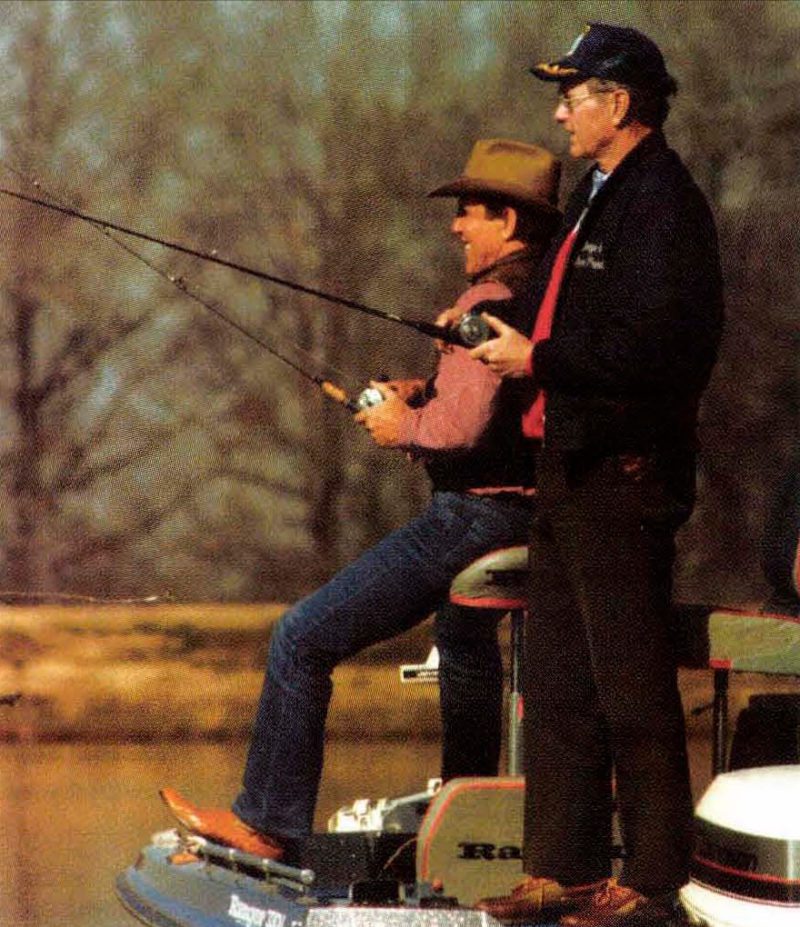

Scott and former president George Bush still get together to fish. He enlisted Bush’s support for a bill that established a tax on fishing equipment that provides $140 million a year for state fisheries programs.

Regardless of what you call him, the first tournament, held June 6-8, 1967 on Beaver Lake near Springdale, Arkansas, was a success, an enormous success.

It drew 106 fishermen from thirteen states. As Scott relates it, this was the first time a tournament had been held on such a scale, and it was the beginning of the bringing together of top-flight anglers to share a great pool of knowledge about bass fishing. The Chamber held a party; Joe Robinson gave him a plaque. Dr. Stanley Applegate, and his wife, got their $3,500 back.

Renowned outdoor writer, Homer Circle, who lived in Rogers, Arkansas, wrote the first news copy on Scott and B.A.S.S. Scott recalls a portion of the column word for word: “I tips me hat to the insurance man, Ray Scott, for pulling off the unbelievable.” Actually, the “unbelievable” was just beginning.

On the 600-mile drive back home, Scott made a decision. He had been working for an insurance company, something he had started doing in college and had continued since graduation. He would quit his job and devote his life to promoting bass-fishing tournaments. He had been an enthusiastic angler since childhood, biking three miles out of Montgomery to a little stream known as Three Mile Branch – with a cane pole and a cigar box of tackle – to catch bluegills his mother cooked up. Now, he felt full force “the heat and enthusiasm of bass fishing.” He took a leave from his insurance job, renting an office for $30 a month just across the hall. He borrowed a desk and some chairs, hired another secretary, this time a former high school sweetheart, Sarah Smedley, under the same conditions as he had Darlene Phillips. “You’ve got a job, but I can’t pay you.” With three small children, house and car payments, Scott was laying it all on the line.

He put together the second tournament, with 116 anglers, in October on South Lake in Alabama. The third tournament was held on Lake Seminole. As Scott observes “It just kind of kept pyramiding.”

The success of the tournaments, however, did not translate directly into a living. He needed capital to continue to grow. He had a small office, an unpaid secretary; he had stationery, B.A.S.S. patches he had designed, membership forms and a small but ardent following. What he needed was $10,000 to do a mass mailing. The post office wasn’t about to give him credit, and banks, understandably, did not see Scott and his fledgling organization as a sound place to invest their money.

Enter another angel in the person of Don T. Butler, the very first member of B.A.S.S., who loaned Scott $ 10,000 for the mass mailing. Scott and his family licked stamps and envelopes “until we couldn’t open our mouths.” Ten days later, he paid Butler back the $10,000, and B.A.S.S. was on its way to becoming the far-flung fishing organization and premiere sponsor of bass angling tournaments it is today.

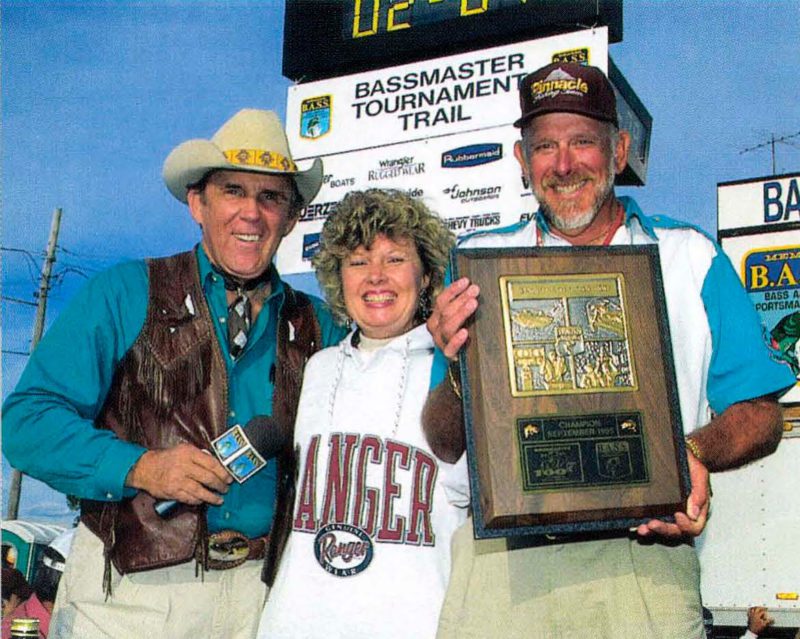

Watching Scott emcee a tournament is a little like watching an evangelist before a congregation of adoring believers. He works the cheering throng, shouting, cajoling, teasing, his voice rising and falling as he spurs them to a suitable fervor. He commands the crowd to stand, and they stand. He urges them to cheer even louder, and they oblige. Someone who finds in fishing solitude, quiet and an escape from the hype and stress of daily life may find the B.A.S.S. Master Classics tournaments a crass spectacle, produced with all the subtlety of a Super Bowl half-time show. As the promotion for the show announces, it is a fanfare of “laser lights, fog machines, big screen TV, flag-waving, gospel music, country music and indoor fireworks.” Some might call it tacky.

At the weigh-in at the end of each day, boats are towed into the arena with the fishermen riding like Romans in their chariots. With much ceremony, the fish are yanked out of the live-wells and lifted overhead to a cheering crowd of 20,000 fans. The fish are placed in a laundry basket and weighed. Scott stands at center stage. At six-feet-two and sixty-two years of age, he still shows the athletic build of the football player he was in high school and his first two years at now defunct Howard College, where the senior quarterback was another one-day-to-be famous Alabaman, Bobby Bowden.

Scott stands tall on the platform, like an Old Testament prophet incongruously attired in white Stetson, fringed jacket and western-style shirt. He exhorts the audience and builds suspense as the weigh-in progresses, shouting encouragement. “Oh glory!” and “Come on! Come on! Twenty-one pounds and one ounce. We got us a new tournament leader.”

The competition itself draws in excess of 100,000 fans. In the process of setting up these tournaments, Scott has turned professional bass anglers into celebrities, and more than a few of them into millionaires, men who sign lucrative tackle endorsements and make a living from fishing. The fact that these are mostly middle-age white guys, guys who, shall we say, are more likely to be endorsing grits and gravy than Slim-Fast, is probably part of the appeal. I’ve long ago given up the dream that I was going to be roaming right field for the Detroit Tigers the way my boyhood hero, A1 Kaline, did. But, hell, I can catch fish.

Of course, not everyone is equally skilled at catching fish. Anyone who has been in a boat with a professional bass angler, or other talented guide, quickly learns that they know more, react faster, and on any given day will out-fish the average plug-castin’ Joe. As Scott points out, these tournaments separate good fishermen from great fishermen. By bringing together the very best, one result has been a boom in technique and tackle, not to mention the various gadgets and gizmos that will ostensibly make one a better bass fisherman. The tournament’s broadcasts are narrated by a former champion, Ken Cook, who provides golf-style commentary, in the process imparting much information about how to fish for bass – from structure to weather and water to lures and casting techniques.

Such tournaments are not without their critics. Aside from making a competition and a spectacle of what many consider the noble and gentle art of Ike Walton, the tournaments are also criticized as having an adverse effect on fish populations. As fisheries biologists have pointed out, catch- and-release does not automatically guarantee the survival of the fish, and the ceremony of the weigh-in can only add stress. Scott notes that in early tournaments, fish were kept, killed and donated to charity, a practice he sees now as wrong. But he is quick to point out that tournaments switched to catch-and- release, which he has promoted as a practice among folks who at one time would have kept everything they caught. He adds that over 97 percent of the fish caught in B.A.S.S. tournaments survive, even when delayed mortality is factored in.

B.A.S.S. is what Ray Scott is known best for, but it is not his sole interest or accomplishment. He is also an ardent hunter and the founder of the Whitetail Institute of North America, a for-profit organization that sells forage seed formulations to hunters and landowners. Some profits are used to support research on the whitetail deer.

He also talked former President Bush into committing himself to a tax increase long before the congressional Democrats and Bush’s “Read my lips. No new taxes.” debacle. Specifically, Scott enlisted Bush’s support of what became the Wallop-Breaux Bill, a user tax on fishing equipment that provides $140 million a year for state fisheries programs. As Scott tells it, he and Bush met in downtown Montgomery and “I beat him to death with that idea for a bill.” This was just the beginning of a close relationship with the former president, as Scott served as chairman for the Bush presidential campaign in Alabama in 1979. Though Bush lost to Reagan (“I’m not sure that even God could have beat the Old Man,” is how Scott describes Reagans victory), he and Bush still get together to fish.

Though still serving as president of B.A.S.S., Scott no longer oversees the day-to-day operations of the organization, and he has cut back on emceeing tournaments. In this so-called retirement, Scott has devoted himself to yet another great interest. It couldn’t, of course, be something as simple as wood-burning humorous signs or making bird feeders out of plastic soda bottles to sell at local craft fairs. No, Scott’s new passion is building lakes. He’s designed and built them as small as two acres and as large as fifty-five. He’s at work on a four-volume set of videos, due out in the fall of 1996, that will bring together the expertise he has developed. These tapes will cover everything from site selection to creating structure, balancing the environment and lake management.

When all is said and done, just who is Ray Wilson Scott, Jr.? Promoter par excellence. Empire and lake builder. Deer hunter and bass angler. Conservationist. A man who, though he says he “nearly majored in freshman English” in college, is a natural-born story-teller. If you ask Ray Scott a question, don’t expect an answer, expect a story, perhaps several, twining together like Spanish moss in an old oak tree.

In our four hours of conversation, he groped for a response only twice. The first time was when I asked him why he fished. He thought a while before responding, and his response was as eloquent as any I’ve read among the more esoteric literature of flyfishing. “A beckoning to the water is in the soul of all men.”

The second time he was momentarily stumped was when I asked him what he would like on his epitaph. The pause was even longer this time. Finally, he replied: “What a ride! What a ride! It’s been wonderful!”

It fits. Scott seems genuinely amazed at what has happened to him, going from a struggling – but talented – insurance salesman to a man recognized by tens of thousands, who flies around the world in his company’s Lear jet, who owns a ranch in Alabama and a camp in the mountains in Mexico, who fishes and hobnobs with presidents and corporation executives, who has “more money than I can ever spend in this lifetime.”

Once he told his pastor in Pintlala, the Reverend Gary Burton, about the amazing series of coincidences that have affected his life. Scott described these coincidences as “like having a pair of dice and rolling seven a hundred times in a row.” The Reverend Burton had another explanation. “Did you ever think, Ray, that coincidence is just God’s way of remaining anonymous?”