Lessons in Cold War economics and stag hunting with the KGB under the hammer and sickle of Soviet Communism.

Did I ever tell you about the time I paid a hundred thousand dollars for a deer? The money wasn’t mine of course, and it was in rubles, Russian money, but that’s what the tab came to in American money.

The whole thing happened several years ago, before the fall of Soviet communism, and the Russians wanted to do some trading with an American computer manufacturer. (I’m going to leave out some names, and change those of the Russians involved, because for all I know they could still get in trouble over what happened.) What they wanted were not the type of high-powered computers used for strategic military purposes or stuff like that, and in any event we couldn’t sell to them anyway, except for ordinary PCs for innocent chores like library retrieval and medical records.

As it happened, there was at least one U.S. maker of such computers willing to do business with the Russians, but the catch was they didn’t want Russian money. The reason being that Russian bucks – rubles – were virtually worthless out of Russia, and for that matter not worth much inside Russia either. But more about that later.

So what the Russians had in mind was swapping some of their products for our computers, and among the items they wanted to trade were guns. Mainly sporting shotguns. The U.S. computer company was interested in trading for guns, but they didn’t know anything about Russian shotguns or the American gun market. And that’s how I came to be involved.

The deal they offered was irresistible: two Americans, my good pal John Amber, the legendary editor of Gun Digest, and myself, accompanied by a trade specialist from the computer company, would visit some of the Russian gunmakers and size up what they had to offer, then give our opinions as to what appeal Russian guns would have for American hunters. In return for our services, they would treat us to an exclusive hunt for Russian stag, plus some waterfowl hunting in one of their preserves.

On top of that, they promised a private tour of the fabled gun collection inside the Kremlin itself. I would have been happy to go just for a peek at the gun factories and Kremlin tour, so the hunting was gravy. But first I had to be convinced that everyone was on the up and up about the computers to be swapped, that they were not to be used for strategic purposes, and that I would not be aiding and abetting our Cold War enemies.

As it turned out, even our State Department was in favor of the deal, so I agreed to go, and it came to pass that on a drizzly November evening, I found myself in the dark and dreary bar of a Moscow hotel in some rather mixed company.

Aside from Amber and myself, there was the American trade specialist, whom I’ll call Dave, and another American, Roger Barlow, whom I’d met before. Barlow, in addition to being a firearms expert in his own right, was a cinematographer who had been hired to make a promotional movie of our tour and hunting.

The other members of our suspicious-looking group were Hans, an Austrian who looked after the computer maker’s affairs in Europe, and Viktor, a Russian whose English-printed business card proclaimed him a “Consultant for Technical Product Trade Alliances,” or some such hopelessly unfathomable bureaucratic title.

Viktor and I hadn’t hit it off very well at first, beginning with my rather discourteous inquiry if it were possible to get a gin and tonic in Russia, followed by his scowling admonishment that they were not uncivilized bears. As we sat glaring at each other and contemplating an escalation of the Cold War, Hans relieved the growing tension by asking if we would like to go upstairs and see the money.

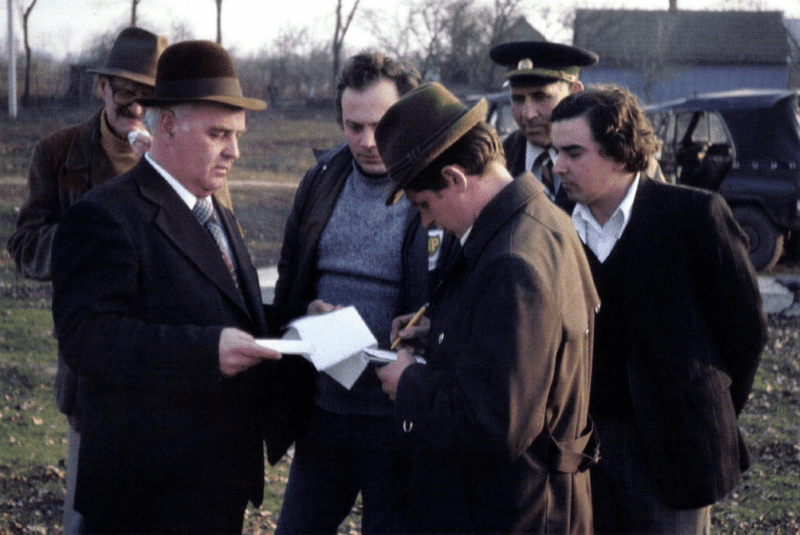

Carmichel (third from left) poses with foresters and the hunters in front of the Russian lodge. Viktor (far left) was assigned by the KGB to keep tabs on the author.

“The what?”

“The money,” he replied, chuckling at my befuddlement, then began explaining the peculiarities of doing business with the Soviet government.

As the ancient birdcage-shaped elevator creaked and bumped its way to the top floor, Hans let us in on the strange fact that the Soviets paid cash in their international trade deals. The catch to paying rubles on the barrelhead, however, is that the money is almost worthless and besides that, it couldn’t be taken out of the country. Which is why their so-called cash business had to be propped up with trades for Russian goods, such as the guns Amber and I had come to have a look at.

As a result of such dealings, so much Russian money had been accumulated by his company that Hans had rented a hotel room to store it in. In fact, the entire top floor of the hotel!

“Why bother with a bank,” he further explained, “when rubles aren’t worth stealing.”

And having thus explained what we were about to see, Hans produced a key and swung open the door of a large room. And there, in great piles in the middle of the floor and terraced against the walls, were big bundles of rubles, all in large denominations.

Astonished by so much money lying around relatively unguarded, I was somehow reminded of the Donald Duck comic books I’d read as a kid, in which Donald’s Uncle Scrooge McDuck hoarded huge piles of money that he played with like a child in a sandbox.

“Part of my job,” Hans went on after my companions and I had recovered our collective breath, “is to look after this money and keep inventory. Fresh piles of rubles come in pretty often.”

“But what will become of it?” I had to ask.

“Who knows,” Hans answered with a shoulder shrug, as if he had no particular interest. Shrugs, as I was to learn in coming days, are part of the Russian language. Especially in official circles.

Over the next three days we looked at guns, were escorted from place to place like dignitaries, indeed saw the Kremlin gun collection, and ate some awful meals (I’ll tell that story another time). We also did some skeet shooting with Eugene Petrov, the Olympic gold-medalist shooter (I let him beat me because it was the politically polite thing to do), saw the changing of the guard at Lenin’s tomb, and took in a wonderful performance at the famed Bolshoi Ballet.

After the ballet, we attended a fancy reception at one of the gilded and chandelier-hung government palaces. Most of the attendees were military types, each of whom was festooned with yards of gold braid and acres of service medals, so I figured they must be important guys. They seemed to be bored with the affair and indifferent to their American guests, eagerly consuming vodka and caviar with the same single-minded diligence I’ve observed when dealing with American bureaucrats.

Meanwhile, Viktor and I were hitting it off better. He spoke American English with a New York accent that he picked up when he was a member of the Soviet delegation to the U.N. He was a man to be liked, I discovered during our jaunts, but also a man to be feared.

I found this out late one afternoon, after he and I had been on a walking tour of Moscow and decided we were too far from the hotel to walk back and had better take a taxi. There were plenty of empty cabs going by, but none seemed interested in stopping, apparently because their daily quotas had been filled and they were just joy riding. After several minutes of fruitless cab hailing, Viktor calmly stepped into the lines of traffic and held up his hand so the oncoming cabs could see what he held in his palm. From my angle I couldn’t see what he was holding, but it was powerful stuff because a half-dozen or so taxis screeched to a halt, their drivers tumbling out and jerking the rear doors open for our entry, all grinning and bowing like boys caught misbehaving.

We selected the cleaner looking and best repaired of the taxis. Once inside, I took a long look at Viktor and suddenly KGB flashed in my mind like a fluttering neon sign – the dreaded Soviet Secret Police.

So that’s it, I realized, Viktor’s job is to keep an eye on us and make sure we don’t get into trouble.

He must have sensed my questions in the making because before I could speak, he simply shrugged and settled back for our silent ride through the darkening streets of Moscow. When we arrived at the hotel a light snow had begun to fall, and I wondered if I was seeing the beginning of the Russian winter. It had defeated Napoleon’s might and a vast German army. Would a couple of American gunwriters fair any better?

Carmichel grips a cluster of bloody oak leaves, which in accordance to Russian tradition, he then placed inside his cap.

According to our schedule, we were to fly several hundred miles south of Moscow to the city of Krasnadar, and from there, drive to a camp where we would hunt the fabled Russian stag. None of us, Viktor included, had any idea what a Russian hunting camp would be like or what services it would offer. So, to be on the safe side, we figured it would be wise to stock up on some caviar, smoked salmon, and other such nutrients vital to survival in a hunting camp. And a few bottles of vodka wouldn’t be a bad idea either.

To pay for these necessities, we raided Han’s hoard of rubles at the hotel and filled a scuffed and ancient crocodile suitcase we found in one of the rooms. But as it turned out, the foodstuffs we needed were not available at the bare-shelved peoples’ markets. In order to buy caviar and other such desirable Russian goods, we had to go to relatively swanky, state-run shops that catered only to foreign currency, preferably U.S. dollars. When we flipped open our ruble-stuffed suitcase and offered to pay in local greenbacks, the husky saleswoman scowled and slammed the lid closed.

“Nyet.”

It’s about $3.50 U.S. for one ruble. The illegal street exchange rate, however, was about ten rubles for a single dollar. The ridiculous exchange rate, as it turned out, was to bring our hunt to an almost unhappy conclusion. The shopping tour was a lesson in Soviet economics, but not particularly a surprise because after the previous days in the capital city, I was getting a clearer idea of what Winston Churchill had meant when he said, “Russia is a riddle inside a puzzle wrapped in an enigma.”

When we got back to our hotel, laden with our survival foods and finished packing for departure for the airport, another Russian mystery presented itself: Viktor’s almost psychotic fear of flying. Only he didn’t tell us of his fearful distrust of flying on Aeroflot, the Soviet State airline, but rather, lied about the airport at Krasnadar, our destination, being closed for repair and that we would have to go by train. His explanation about the closed airport seemed a bit thin, but no one questioned his motives except to ask if train reservations had been made.

Viktor shrugged, “We’ll take care of that when we get to the station,” and I had visions of us crammed into a drafty boxcar filled with smelly peasants and chugging across a frozen landscape like in a scene from Doctor Zhivago.

The reality of the train we were to take was pleasantly different. It was huge, with tracks of a wider gauge than ours, and pulled by a gigantic, gleaming engine surmounted by the symbolic hammer and sickle of Soviet Communism. But very uncommunistic, for a supposedly classless society, was that the train offered four classes of travel. Upon learning this, we naturally hoped that we could get First Class seats, but without prior reservations it seemed doubtful.

”I’ll see what I can do,” Viktor shrugged and casually approached a pudgy, cheery-looking young woman, dressed in what looked like a stewardess uniform, standing by the steps of the yacht-like First Class car. He spoke quietly to her for a moment and was answered by a vehement shaking of her head and a flurry of negative hand gestures. Clearly, there was no First Class space available, and I was resigning myself to travel among the deodorant-challenged masses when Viktor gently took the stewardess by the arm and walked her a short way down the platform with their backs to us and out of hearing. When they returned, she climbed into the First Class coach and Viktor walked over to our apprehensive group.

“It will be a few minutes…she is reassigning the First-Class compartments, and then we will get on board.”

Viktor’s mysterious badge had again worked its magic.

The trip to Krasnadar lasted 28 hours, and as the giant train roared through miles of primeval forests and across seemingly endless plains, I saw firsthand the abject failure of communism: wheat fields big enough to feed a nation were littered with abandoned farm machinery, while in the villages, horses tugged carts along muddy streets. Wandering through the crowded lower class coaches I saw only sullen faces until I reached Fourth Class, where some turbaned Kuzaks were cooking over tiny alcohol stoves. A woman, probably younger than she looked, with her head tightly swathed in a patterned shawl, smiled at me with government-issue stainless steel teeth and invited me to eat with them by pointing at a steaming pot and patting her stomach. It smelled delicious.

The only other sounds of gaiety I heard as the hours passed were uproarious laughter and shrill giggles from a compartment near mine that was inhabited by two Soviet generals and a couple of women who looked too young to be their wives. On the few occasions any of them emerged from the compartment, they wore faces of solemn dignity, but when the door closed, the giggling would resume. In our own compartments the supply of caviar and salmon diminished at a steady rate and was completely gone by the time our train arrived in Krasnadar.

Which was just as well because our hunting “camp” was a villa once used by the Czars of Imperial Russia and their hunting buddies. It was fully staffed by cooks and maids and gamekeepers who wore the traditional European gamekeeper’s insignia of oak clusters but entwined in their gold-embroidered leaves was the hammer and sickle.

After many introductions to officials whose names I couldn’t possibly understand or remember, we were ushered into a small meeting room with a podium over which hung a portrait of Lenin sitting by a campfire, shotgun over his knee, and apparently haranguing a cluster of fellow hunters. A white-uniformed maid, as sour looking as she was fat, served scalding tea marble-hard biscuits after which the chief forester welcomed us briefly in passable English, then went about the serious business of explaining the rules of Russian hunting.

His main concern, it seemed, was that we understood their trophy scoring system and, using charts and diagrams, detailed the measurement methods and how a monetary value was attached to various trophy points. At the time I was under the impression that I was a non-paying guest and paid little attention to the price tags attached to various parts of a stag’s antlers, but I couldn’t help but note the distinctly capitalistic way they were intent on profiting from their deer herd.

That evening, over a meal better than anything we’d had in Moscow, the vodka left over from our train ride disappeared. As it did, the stony-faced local officials became increasingly convivial and the foresters who would be our guides on the morrow raised endless toasts to our coming success.

The Russian stag we were hunting is more commonly known throughout Europe as red deer and is a cousin to North American elk, though somewhat smaller and with a rather different antler configuration, typically branching into a cluster of points at the upper ends. On the better trophies these upper points may palmate into cuplike formations called chalices. The Soviet pricing schedule put a high value on fine chalices.

On the morning of our hunt we were issued our rifles, which were Baikal Medveds. (Baikal is the trade name applied to most Russian sporting arms, more or less the equivalent of Remington or Winchester.) The gas-operated Medved autoloader, even with its checkered sporter-style stocks, has distinctly military parentage with an over-the-barrel action rod and military-style sights similar to the Simonov and AK systems. The caliber was 9mm and looked something like a .35 Remington but a bit shorter.

When I asked for ballistic details, I was answered with a shrug and told it was called “deer.” Another sporting caliber, I learned, is called “bear.” Which probably means that Russian big game hunters don’t have much to debate or choose from in the way of calibers. Only one of the rifles had a scope – a stubby low-power model that looked to be of WW II sniper vintage, which John Amber opted to use.

The vast woodland around us was known as the Red Forest, which was no surprise as they attached the color of revolution communism to about everything (Red Square in Moscow, for example). The deer are hunted from stands with beaters driving the game toward the guns.

The stands turned out to be impromptu hiding places selected by our individual guides. My chain-smoking guide spoke no more English than I spoke Russian and carried a battered bolt-action rifle of ancient origin. Despite the language barrier – or because of it – we got along pretty well with the sign language that hunters communicate with the world over.

A Russian guide with the author’s big jackal.

On the first drive we spotted a jackal zigzagging in our direction. I wasn’t sure if it was on the shooting menu and raised my eyebrows in the universal questioning expression. He responded by nodding in the affirmative, touching my rifle and making a shooting gesture. So when the jackal came within about 25 yards, I killed it with an easy shot. This pleased the guide immensely, who pantomimed that he would take the skin and make it into a fur cap.

When I fired at the jackal, the front sight fell off my rifle and was retrieved by the guide after a brief search in the leaves. He slipped the sight back onto the muzzle – still as loose as before –and smiled with satisfaction at the repair.

Now it was my turn to shrug, and I made a mental note to recommend that the Medved not be imported for American hunters. There were two drives that morning and on the second drive we heard a couple of nearby shots followed minutes later by a running Viktor, explaining that he had wounded a stag and asking if it had come our way. We had seen nothing.

On the second day of our hunt, I was stationed at the edge of a vast, recently plowed field. Two deer had been bagged the previous afternoon, plus the wounded one Viktor was still tracking, but I had seen nothing. More and more I was blaming my poor luck on my guide’s incessant cigarette smoking, which was probably spooking any deer headed our way. Just as I was contemplating a complaint to the head forester, the guide made a hissing sound and nudged me toward the open field. There, coming in from an angle that would bring them within 75 yards, was a gang of five or six stags running in a loose bunch. All had good antlers, and as far as I could tell, each was good as the others so I simply swung the loose sights of my Medved ahead of the lead stag and pulled the two-stage trigger.

The shot had no effect that I could see except to turn the deer toward the safety of the forest. Just before they disappeared, I fired again, with no apparent effect. I was disgusted with my bungling shot and with myself even more for being so dumb as to hunt with a rifle without having had a chance to check its zero.

But just as I was beginning to utter my disgust, the guide put his cupped hand behind his ear, pantomiming hearing a distant sound, then pointing in the direction where the stags had disappeared. Then he broke into a big smoky grin and made a downward motion with his hands. I had hit the stag and it was down!

The next morning the Russians turned out in their best medal-bedecked suits and uniforms and presented us with rather elegant-looking certificates, which on closer inspection turned out to be scorecards tallying the points of our trophies. Handshakes and solemn congratulations were offered, and at the conclusion of the ceremony, a calculator was produced and it was obvious that rubles were being converted to U.S. dollars.

After considerable whispering among themselves and a bit of smug giggling, they presented us with our individual bills. Mine came to something a little over a hundred grand, and the main bureaucrat who handed us our bills stood in front of me in smiling anticipation, as if he thought I had that much cash on me and was going to hand it over.

The night before, Dave had warned us that the Russians would probably try to milk us for a bunch of dollars and outlined what our response was to be. Since I was the first of our group to be presented with the outrageous bill, I was the first to speak. I savored the moment.

Red Forest officials tally the huge cost of the author’s stag hunt, hoping to be paid in American dollars.

“You wish to pay in American, no?”

“Nyet,” I replied, returning the bureaucrat’s smile and ignoring his proffered bill for American money. “We’ll pay in rubles…your money.”

“Viktor, open that old suitcase so we can pay these guys off and get out of here.”

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form —until now.

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form —until now.

Classic Carmichel features nearly 400 pages of hunting adventures and firearms expertise by Carmichel, widely acknowledged as one of the foremost experts on sporting arms.

Carmichel’s exploits and prowess had no equal during what is arguably the Golden Age of international hunting and shooting. These are not just stories by a well-traveled adventurer—they are pure literature, written with a style and eloquence that deserve inclusion in any collection of great outdoor books and writers. The big 9 x 10½-inch book features more than a hundred never-before-published photographs. Buy Now